"Every perfumier shall have his own shop, and not invade another's. Members of the guild are to keep watch on one another to prevent the sale of adulterated products. They are not to stock poor quality goods in their shops: a sweet smell and a bad smell do not go together. They are to sell pepper, spikenard, cinnamon, aloeswood, ambergris, musk, frankincense, myrrh, balsam, indigo, dyers’ herbs, lapis lazuli, fustic, storax, and in short any article used for perfumery and dyeing. Their stalls shall be placed in a row between the Milestone and the revered icon of Christ that stands above the Bronze Arcade, so that the aroma may waft upwards to the icon and at the same time fill the vestibule of the Royal Palace ... When the cargoes come in from Chaldaea, Trebizond or elsewhere, they shall buy from the importers on the days appointed by the regulations ... Importers shall not live in the City for more than three months; they shall sell their goods expeditiously and then return home ... No member of the guild may purchase grocery goods or those sold by steelyard. Perfumiers shall only buy goods that are sold by weight on scales ... Any perfumier who currently trades also as a grocer shall be allowed to choose one or other of these trades, and shall be forbidden henceforth to carry on the trade that he does not choose.".

Regulation regarding the operation of Perfume Shops in Constantinople

Throughout it's history the city of Constantinople was covered with both wild and cultivated roses. Even today you see roses everywhere in Istanbul. They became an important part of Ottoman culture and traditions. The area of the Great Palace of the Byzantine Emperors has become "Gülhane Rose Park".

During the last years of the Byzantine Empire, after 1400, The Ottoman Turks had the city under siege for decades in a Stalingrad WWII-like situation, choking the city off in stages and by degree. The first Ottoman blockade of the city lasted for 12 years - between 1390 and 1402, first interrupted by the Crusade of Nicopolis, then lifted due to the Battle of Ankara when Mongol armies defeated the Turks in battle. This blockade was highly effective and resulted in many of the city's inhabitants abandoning the city - especially the nobles. After the blockade ended many people returned and there was a temporary revival in the economy. There was hope that the Turkish menace had ended. Just a few years later they were back. The next siege of Constantinople, in 1411, was a short one that was unsuccessful. Eleven years later, in 1422, the Ottoman army was back and mounted their first large-scale siege of the city which was also unsuccessful. The last siege, in 1453, was successful and was one of the turning points in history.

Most of the population had fled the city in those decades. During the 12 year long blockade there was a shift of the growing of foodstuffs from outside the walls to inside them. Vast tracks of the city were converted to vegetables, wheat fields, vineyards and orchards. This accelerated a trend of de-urbanization that had begun in the middle of the 14th century during the terrible civil wars that plagued Constantinople as the Palaeologans and other nobles fought for control of the of what was left of the empire. One can imagine palaces and churches being gradually overgrown with vines and roses like Sleeping Beauty's castle. Despite their seeming abandonment the buildings and land was still owned by great "houses" - monasteries and merchant companies or families. For example, in 1351 the Panagiotissa convent owned properties located on the hillside below the Phanarion quarter that included houses, a bath, gardens and a vineyard. The great cathedral church of Hagia Sophia owned shops and farms around the city. The people who lived and worked on the land in the city were tenant farmers.

Roses hedges were grown all over the city. These hedges could incorporate multiple types of climbing roses grown together, with the long canes woven in and out. They were highly effective in keeping animals - and robbers - out of cultivated gardens.

On the left is a 6th century Byzantine cosmetics jar in rock crystal, gold filigree and topped with a blue sapphire.

The roses of Constantinople were mentioned by travelers to the city. They were one of the most interesting natural features of the city. Roses were the royal flower for Byzantine gardeners. We know the Byzantine Emperors were avid growers of roses for their flowers, fragrance and medicinal qualities. When the Emperor traveled his entourage packed a special silver cooler with a cover for his rose oil - rhodostagma, which was an extract of roses prepared with honey. Essence of roses was an essential product in the Byzantine pharmacy, rose water is called zoulápin in Byzantine Greek.

The Byzantines were the first to make rose sugar, which was a popular medieval sweet. Rose water also was mixed with salep, a flour made from crushed orchid tubers, and drunk as a fortifying beverage as early as the seventh century in Constantinople. The drink was very popular in Ottoman times and is still served in Istanbul. Wild orchids in Turkey are going extinct because of the trade in salep flour. The Byzantines also mixed rose syrup with crushed mountain ice to make sorbet. Perhaps that is what the Emperor used his silver cooler for.

It's funny that the early Christians opposed flowers and scents in worship because they had been associated with pagan ceremonies for gods like Apollo and Aphrodite. Christians were warned that demons would attack and possess you if you associated with roses and perfumes. Two hundred years later Christians are instructed that the scent of roses now drives demons away!

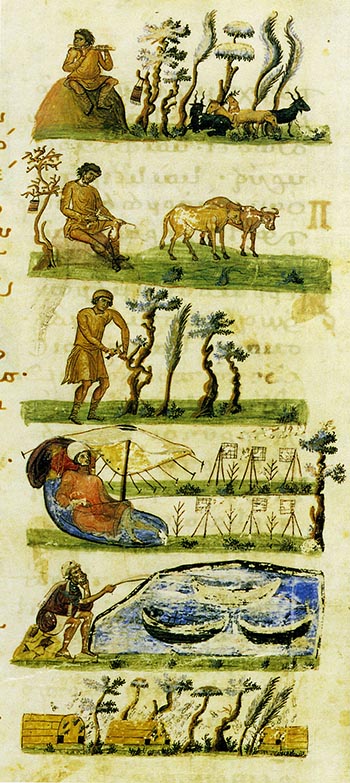

The Geoponica is a twenty-book collection of agricultural lore, compiled during the 10th century in Constantinople for and dedicated to the Byzantine Emperor Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus who reigned from 913-959. The Geoponica was compiled from many earlier sources and then adapted for the Byzantine gardener. The Greek word Geoponica signifies "agricultural pursuits" in its widest sense. Flowers are covered in detail, with practical advice on how to grow them successfully - and in the case of roses - to extend the blooming season - even until January. We also learn from the Geoponica on how to get the strongest - the sweetest - perfume. All of this advice is specific to Constantinople and applies to every type of garden in the city. The advice given could be applied from a small home garden to an Imperial one. Of course you had to have access to these 20 volumes and be able to read to benefit from them. Multiple copies where to found around the city and could be borrowed, copied or purchased in book stores. It was used in Constantinople right up until the fall of city. It was extremely popular all over the the Byzantine Empire and the middle east and was translated into many languages, including Persian and Arabic.

From the Geoponica (on the right) we get the following advice on growing roses in Constantinople. The gardener is encouraged to plant lots of them:

From the Geoponica (on the right) we get the following advice on growing roses in Constantinople. The gardener is encouraged to plant lots of them:

"The entire space between the trees ought to be filled with roses and lilies and violets and crocus, which are most pleasing to sight and smell and usefulness (medicinal), as well as profitable (income-producing) and beneficial to bees."

If you want the sweetest smelling roses you should plant garlic nearby. Roses and lilies grown in dry conditions are also sweeter smelling. If you want blooming roses all year round plant them monthly and use lots of pigeon manure to fertilize them. It is easy to propagate roses by digging them up and dividing the plants. Roses should be planted a cubit apart (same as today). If you want early blooms plant them in pots in greenhouses. Another method is to plant them in your garden with trenches and pour warm water into them twice a day in winter and early spring.

The dew from roses can be gathered and used as a remedy for eye problems.

You can keep roses fresh by dipping them in amurca liquor, a dark, bitter-tasting, sticky, viscous liquid, which settles at the bottom of olive oil containers over time. It is a thick olive oil that was used was a preservative, fungicide and fertilizer in ancient times.

Roses can continuously produce flowers into January if you water them twice a day in summer. Obviously from this advice we must be dealing with a repeat-blooming (unfortunately unnamed) varieties. You can keep roses fresh by placing them in a reed and tying the reed with papyrus. The Geoponica tells us can we can make roses white by exposing the buds to sulphur. I have never heard of that before! Perhaps someone should try it. Preparing a good rose bed and pruning are essential. The root of the rose tree saves people who have been bitten by snakes.

Special rose varieties were grown in the Imperial gardens and around the city. Pliny has written about the roses of the the Roman Empire. He spends considerable time of the most popular varieties grown and made a list of eleven that were most important. Like today many of them had no fragrance and were grown just for their flowers.

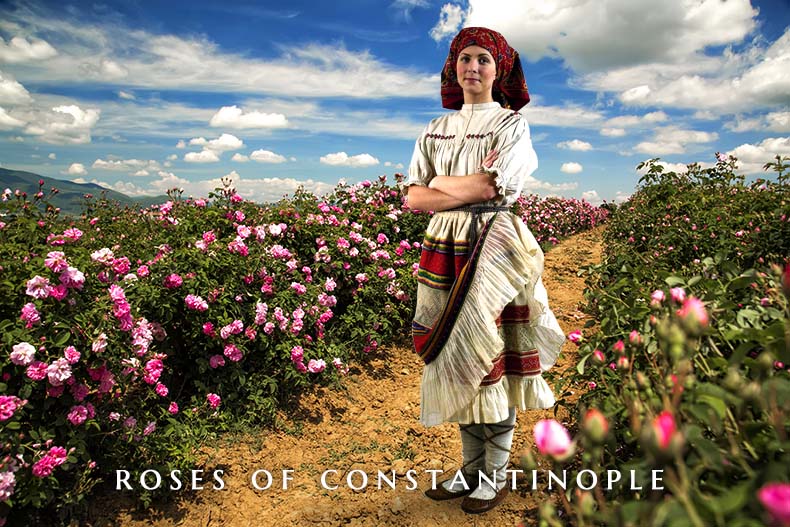

Of these the ones we can consider candidates to be roses of Constantinople are the the following native plants in the territory of the Byzantine Empire. The Trachinian (red) rose appears to have been a native of Thessaly, and grew near the city of Heraclea in Greece. The Milesian (strong red) and Alabandic (white) roses were other roses from Greece and Asia Minor, the former deriving its name from Miletus, a city in the Island of Crete, where it was first found; the latter from Alabanda, a city of Caria, in Asia Minor. Rosa Centifolia (pink), or hundred-leaved rose - the ancient cabbage rose, had many small petals. It grew in Greece near Philippi; to the latter place, however, Pliny says it was not a native plant. It grew also in the vicinity of Mons Pangaeis in Thrace; where it was grown commercially. This is the same general area where Bulgarian roses are grown today in the "Rose Valley" of Kazanluk.

The Sweet-Brier Rose - Rosa Eglanteria - Shakespeare's favorite rose - is native to western Asia Minor and was grown in Constantinople. One of its advantages is it blooms over a long period of time - almost two months and its leaves smell sweetly of apples. It grows wildly by runners and can overwhelm small buildings if not kept under control. Therefore, it makes a perfect rose-fence. This rose is used to make rose water in Tunisia, a tradition that dates back to Roman times. That's Eglantine on the left.

The Sweet-Brier Rose - Rosa Eglanteria - Shakespeare's favorite rose - is native to western Asia Minor and was grown in Constantinople. One of its advantages is it blooms over a long period of time - almost two months and its leaves smell sweetly of apples. It grows wildly by runners and can overwhelm small buildings if not kept under control. Therefore, it makes a perfect rose-fence. This rose is used to make rose water in Tunisia, a tradition that dates back to Roman times. That's Eglantine on the left.

The Albanic Rose is Rosa Alba-Plena - commonly called the White Rose of York - was grown in Constantinople. The White Rose of York is most famous for its use as an emblem during the Wars of the Roses in 15th century England. The flowers are pure white, semi-double in clusters with a coronet of golden stamens. The fragrance is sublime which explains why the rose is now used in Bulgaria for production of a white rose variety of attar of roses. It has the same beautiful, healthy gray-blue foliage that all Alba roses have and can grow 10-15 tall. It is highly fragrant.

The White Rose of York is seen below:

The rose Pliny calls centifolia is not the same rose we call centifolia today, which is a modern hybrid from the 17th century. Pliny's centifolia was Kazanlik - Kazanluk - Kazanlak, the Damask rose - Rosa Damascena Trigintipetala - now principally grown in the "Valley of the Roses" in Bulgaria for its fragrance and in the production of rose oil. It has been grown there commercially at least since the 16th century. Kazanlik - Kazanluk - Kazanlak was extensively grown in Constantinople. It can grow into huge plants more than 12 feet tall.

It is still found in Isparta, Turkey, where it has been grown commercially for 125 years. Kazanlik - Kazanluk - Kazanlak plants were introduced to Isparta in 1870 by Muslim refugees from the Russian-Turkish war in Bulgaria for commercial growing. They brought seedlings which took 16 years to produce enough petals to produce rose oil. Today Isparta supplies the Great Mosque in Mecca with rose water.

Roses must be cut before the morning dew on their petals dry, and pickers must get the flowers to processing plants within two hours of harvesting to preserve the valuable fragrance. It takes two tons of roses to make 2.2 lbs of rose "butter", which sells for more than $10,000 today. There are 3 quality types, the highest quality freezes at -20-21 degrees Celsius (-4F), second quality freezes at -18-19(-1F) degrees and the third – 16-17 (3F). This Rose "butter" is the essence that all rose products are made from. Even in ancient times rose oil was so valuable that it was faked. Today geranium oil is smuggled into Bulgaria, mixed with a bit of genuine Rosa Damascena oil and then exported as the real thing. Kazanlik - Kazanluk can be seen below:

On the right is a tiny 6th century Byzantine cosmetics jar made of ivory and gold. The handle is a gold cupid.

It is estimated that Constantinople at its height in the 12th century had 2,600 shops lining the main streets averaging 32 x 20 feet in size. Hagia Sophia owned 1,100 of them in the time of Justinian. Can we guess that Constantinople had close to 50 shops that sold perfumes, rose water and rose oil?

Byzantine shops were built of brick, around 33 ft (10m) wide and 22 ft (7m) deep. They had wide openings onto the Mese - the main shopping street of Constantinople - marble framed doorways and floors of both marble and tile. Doors were left open so potential shoppers could see the products for sale inside, and other wares were displayed in front of the doors. Shops had basements and water basins. Stairs lead up to a second floor. There were frequent fires, so stores were often rebuilt over the years. The Mese - and most of the shopping streets - were paved with marble. Many had colonnades with staircases leading to roofs decorated with sculptures that operated like open promenades. The Mese had hanging street lamps to accommodate evening shoppers that were paid for by the city government. In 1332 the famous Muslim traveler, Ibn Battuta, visited the 'bazaar' of Constantinople and remarked that all the shops were run by women and the artisans who made things for the shops were also women. He also tells us the streets and bazaars were paved with flagstones and very spacious.

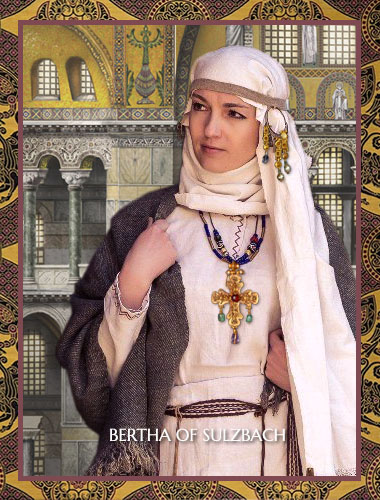

Designs of roses were also worn; embroidered in pure gold - "like lupins" on a reddish-purple maphorion - a type of scarf that covered the head and shoulders, that was paired with a white silk damask tunic which was the official outfit of Imperial Rector of Hagia Sophia given by the Emperor on the day of his appointment. All of these clothes were made in the imperial workshops.

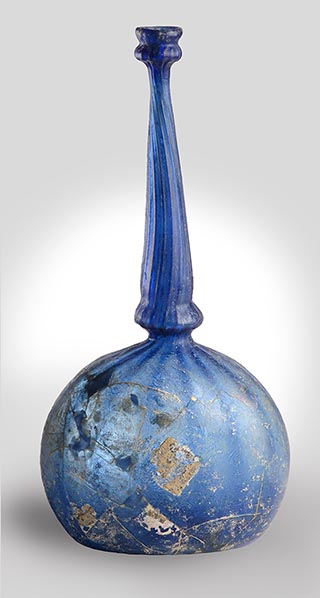

The monasteries and convents of the city were the principal commercial growers of roses that would have supplied them. Although huge quantities of rose petals are required to distill rose scent, and the picking of buds and flowers can be tortuous due to thorns, dried petals are light and easy to transport. Byzantine monasteries were often linked in far-flung religious and business relationships. They were responsible for the distribution of different rose varieties to branches of their monastic houses around the empire and in Serbia, Romania and Bulgaria. A huge amount of rose oil was needed every year for the churches of the city. Mixed in rose water it was used by the clergy to bless the people and anoint holy icons. Many of the glass vessels that have survived from the Byzantine period were sprinklers for rose water. When you received visitors it was customary to anoint them by sprinkling rose water on them. Sprinklers were also used in funerals, and the glass vessel was sometimes left behind in the tomb. This is where many of our surviving vessels have been found.

Perfumes were usually colored, Rose madder was used for red rose. Madder is water soluble and mixes well with rosewater. Fabrics and yarn could be dyed in a rose-scented solution producing pink or dark (purplish) rose colored materials.

There were two types of incense burners used. Large swinging burners were only practical for large halls or churches, like Hagia Sophia or Holy Apostles. There were also hanging and hand-held censers called Katzia which were mass produced. Hand-held censers, made of brass, were used in most mid-sized churches and in homes. They burned different kinds of combinations of gum, resin and scent. Storax, Spikenard, Frankincense and Myrrh were always popular, the supply of Storax, which came from southwestern Asia Minor being the most reliable. In the Pantokrator the typikon specifies the use of Myrrh and Frankincense.

“We offer incense to you, Christ God, as a sweet fragrance. Having received it on your super-celestial altar, send down upon us in return the grace of your all-holy Spirit,” - Symeon of Thessalonke

In the tenth century the emperor Constantine Porphryogennetos tells us that rosewater was used to scent the rooms and great halls of the palace. Even the Senate House received the same treatment in advance of the emperor's arrival. Guests and visiting ambassadors had their rooms liberally doused with the scent of roses and rosewater was left in their rooms in silver basins. Constantine also tells us that he was regularly presented with great wreathes of sweet smelling roses when they were in season. On the Sunday after Easter at the Church of Holy Apostles, as the emperor left, he was presented with 10 wreathes of roses, two at a time by various representatives of circus factions. Sometimes, these were crosses intertwined with roses along with bouquets of flowers. The Church of the Holy Apostles was surrounded by beautiful gardens filled with flowers, perhaps the roses came from there.

When the emperor left the Great Palace to go to Hagia Sophia the streets were prepared with boxwood sawdust, ivy, laurel, myrtle and rosemary. After cleaning, the streets were to be adorned with whatever sweet smelling flowers were in season at the time. Balsam was used to anoint the three crosses made of wood from the True Cross in Hagia Sophia before the emperor arrived to venerate them and then two were taken back with him to the palace.

The passageways of the Great Palace were trimmed with laurel leaves in the form of little crosses and wreathes (there were called stephania which also means an Imperial crown) that were set with seasonal flowers which were called parasols. The pavements of the passageways in the palace were liberally strewn with ivy and laurel, myrtle and rosemary - just like they did for the imperial route to Hagia Sophia.

In the 9th century, when Hagia Sophia received its first figurative mosaics after the end of iconoclasm, the apse and bema was encircled with gold mosaics of flower garlands, which still survive.

In Spring 905, Constantine's father Leo VI, received Muslim ambassadors from Abd al-Baqi of Tarsus in Constantinople to discuss an exchange of prisoners. Leo had won a great victory over the Emirate of Tarsus in 900 destroying their army and capturing the emir himself. The son of the emir was a part of this mission. Leo treated the ambassadors with great hospitality during their stay in the city in part by showering them with luxuries. Though his staff of the bedchamber Leo provided the ambassadors with, "vine flower scent and rosewater, musk, fragrant essences and other perfumes. They washed with the chased silver basins and ewers that were there, and they dried themselves with very precious hand-towels, and they were generously anointed with perfumed oils and sweet-smelling essences and unguents." During a reception for them in the Chrysotriklinos of the palace, surrounded by gold and silver furniture in a chamber hung with gold curtains, the floor was strewn with myrtle, rosemary and roses. Leo VI then took them to Hagia Sophia, which had bedecked with flowers in their honor, and showed them the liturgical vessels, vestments and crosses from the Treasury of the church. This created a scandal because non-believers were conducted through Hagia Sophia and then shown sacred objects. Below is a manuscript illustration from the Madrid Chronicle of Skylitzes showing this event. it's interesting to notice that the columns are black and have gilded ornament in their arches. The Muslim ambassadors would have been escorted along one of the aisles - probably the north aisle - and shown the the items from the Treasury near the great red porphyry columns of the northeast exhedra. The white marble arcades above the columns were gilded, so it really could be showing the event. Pilgrims and visitors to Hagia Sophia were routed from the inner narthex into Hagia Sophia along this route. The Treasury was also on the northeast side of the church. When the mission ended the son of the emir was so impressed by his reception and the luxuries of the city that he wanted to stay longer, even to stay as some sort of diplomatic mission, but his father demanded he return to his own land.

When the emperor returned from an army campaign his route into the city - from the Golden Gate in the land walls to the Chalke Gate of the Great Palace - was to be hung with garlands of myrtle, laurel and roses. That was a great distance to cover. People in the procession also wore these garlands around their necks. When Basil I returned to Constantinople from a military expedition to Tefrike the people met him with crowns of flowers and roses at Hebdomen, just outside the city. All of these flowers and leaves would have been gathered from the vast open spaces and gardens in the city. I imagine they were created by representatives of the guilds and circus factions from the Hippodrome. A big event could strip the city of fresh branches and flowers. All of these celebrations with garlands and flowers was a long standing practice that went back to Ancient Greece and Imperial Rome. It was certainly cheaper than using silk tapestries and carpets to line an Imperial procession - which was also done in Constantinople. Below is a picture of garland of David Austin roses made for the Queen of England. The garlands of Constantinople would have been similar:

It was reported in 2012:

It was reported in 2012:

"The floral arrangements were made by celebrity florist Kitty Arden and her team. She said “When the Queen steps on board we want her to enter a very fragrant environment,” heavily scented roses and herbs helped to make the barge a feast for the senses. Kitty had the help of 40 florists to complete the mammoth task of making 90 garlands from fresh flowers and foliage. Some of the team given the fantastic opportunity to work on the royal commission were lucky students and tutors from Pershore College.

The florists starting preparing the garlands on Monday and worked 12 hour days all week to get them finished. Most of the garlands were 6ft long and required three people to carry them. The garlands were made with fresh foliage and herbs including rhododendron, hebe, lavender, rosemary and bay. Later in the week they were dressed with roses, peonies and carnations."

When the emperor traveled his vestiarion, or private suite, included two large cooler-basins for rose-water. Also in his vestiarion were various perfumes and unguents including:

Incense (probably myrrh from the Commiphora myrrha tree the source of myrrh resin, which is a natural gum. It now comes from India in the form of yellow or red slightly transparent beads or chunks;it should be oily and crumbly.)

Mastic (mastic is a Mediterranean shrub with a nice smelling resin obtained from its branches; it is similar to pine or cedar)

Frankincense (frankincense is also known as olibanum, an aromatic resin used in incense and perfumes, obtained from trees of the genus Boswellia. The word is from Old French franc encens ("high-quality incense"). It comes from Arabia. It is a pale yellow, transparent, resinous substance, dry and hard. Drops of it are transparent, oblong and smooth.)

Saccharin (I couldn't find anything on it, except as a sweetener)

Saffron (stamens of Crocus sativus, is is a small flower in the Iris family. Its profile is bittersweet, leathery, soft with an earthy base note)

Musk (was a name originally given to a substance with a strong odor obtained from a gland of the musk deer)

Ambergris (a waxlike substance that originates as a secretion in the intestines of the sperm whale, found floating in tropical seas and used in perfume manufacture. It is a light, opaque substance, ash colored, sprinkled with small, white spots. It is an earthy odor, that when added to perfumes lends an unearthly delicacy; ambergris burns easily, leaving a golden-colored liquid resin.)

Liquid and Dry Agalloch (the fragrant, resinous wood of an East Indian tree, Aquilaria agallocha, of the mezereum family, used as incense in Asia)

True Cinnamon of the first and second quality and Cinnamon wood (the Byzantines believed that giant "cinnamon birds" collected the cinnamon sticks from an unknown land where the cinnamon trees grew and used them to construct their nests. Cinnamon is distilled from the bark of two species of laurel that flourish in India and China. Cinnamon was much appreciated by the Byzantines, the emperor made an annual present of two apples and a stick of it to select recipients)

Rose scent was also used in incense and candles. Most of the light in churches like Hagia Sophia came from hanging silver candelabra which held glass oil lamps. Some of the most important icon lamps were made in gold, others were made in silver-gilt. A large icon would need a three-light lamp to illuminate it properly. The gift of an icon lamp to be displayed with an important image or in a holy location was a way for a donor to associate themselves with something sacred. The Emperor Manuel I Comnenus made a gift of a huge gold icon lamp set with a glass cup to hang above the Tomb of Christ in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem. It cost 20 talents of gold and had been made for his father John II who died before it could be presented. The lamp carried the inscription "the purple-blooming child, Manuel, the emperor, hangs this on you, oh life-bringing tomb!" and was kept perpetually burning with scented oil. Manuel was buried in the Pantokrator monastery that was founded by his father and mother. Near his tomb was installed a slab believed to have been the stone that Christ's body lay upon after His death; it was said to spotted with tears of His Mother. Manuel had carried this slab on his own back in procession when it arrived in Constantinople. He had a similar gold icon lamp installed here in the Imperial mausoleum of the Comnenian dynasty to hang above the slab.

These same hanging glass oil lamps were used in homes and in Imperial palaces, where scented oil was usually used. Usually a cheaper grade of olive oil was used in lamps and candelabra. Adding scent masked its odor. Spikenard, also called nard, a Valerian plant scent from India was often added to the oil in lamps in churches, especially in the early days of Byzantium. Nard oil was mixed with cinnamon to make the special chrism used during Holy Week in Hagia Sophia. In Imperial Russia this chrism was made in a special ceremony in the Kremlin at Easter time using special caldrons. Nicholas and Alexandra made a special trip to Moscow to participate in the ceremony.

Rose scent was much cheaper and commonly available than nard. Monasteries and private homes could make rose scented lamp oil themselves. The lamps had wicks made of twisted cloth or rope that were floated in the oil and lit to provide light. Scented rose oil was used on special occasions in Hagia Sophia. The altar of Hagia Sophia was regularly washed with rose water. Rose oil was used in vigil lamps that illuminated the famous icon of the Hodegetria Mother of God in her shrine near the Great Palace.

A gilded and enameled glass lamp from one of the Imperial palaces is shown below. Lamps like this were hung from rods or carried and placed anywhere you wanted like candle holders of today.

On the left is an illustration from the 512 Codex of the Byzantine Princess Juliana Anicia illustrating a rose called Rhodon. It is the rose we call Rosa Gallica Officinalis. Rosa gallica officinalis, is a wild, very long-lived rose. It was easy to grow and could spread rapidly by runners. One could create hundreds of plants by cuttings and start your own rose farm with little investment. If other rose varieties were nearby you might get new cross-breeds. This rose should be added to our list of roses grown in Constantinople and it is grown commercially in Bulgaria today.

On the left is an illustration from the 512 Codex of the Byzantine Princess Juliana Anicia illustrating a rose called Rhodon. It is the rose we call Rosa Gallica Officinalis. Rosa gallica officinalis, is a wild, very long-lived rose. It was easy to grow and could spread rapidly by runners. One could create hundreds of plants by cuttings and start your own rose farm with little investment. If other rose varieties were nearby you might get new cross-breeds. This rose should be added to our list of roses grown in Constantinople and it is grown commercially in Bulgaria today.

There were special blends of rose incense from Constantinople that are still made today. Rose water and perfumes were used by the Empress and her ladies (yes, they bathed in rose-scented water), but the common people also loved roses and used rose scent as well. The Byzantine princess, Anna Comnena, tells us how she used essence of roses in an attempt to revive her father, Alexios I, on his deathbed in the Mangana Palace.

Throughout the history of Constantinople there were special shops dedicated to selling perfumes, including attar of roses. Up until the Fourth Crusade the most famous of these were in a row near the Chalke (bronze) Gate of Great Palace and close to Hagia Sophia. It's interesting that barbershops were nearby, which reminds me of Floris on Jermyn Street on London, nearby St. James' Palace. One can imagine visitors to the Imperial Court visiting the barbershops and perfume shops to freshen-up on their way to the palace.

On the right, Rosa gallica officinalis.

The perfume and spice shops were close to the location of the grand bazaar today. The Book of the Prefect, a Byzantine text from around the same time as the Geoponica details the rules for perfume sellers in Constantinople. They were allowed to sell "pepper, spikenard, cinnamon, aloeswood, ambergris, musk, frankincense, myrrh, balsam, indigo, dyers’ herbs, lapis lazuli, fustic, storax" showing they also sold some spices and fabric dyes. (Rose scent is not mentioned because it was produced locally and was unregulated.) Spice shops governed by their own rules and there was a bit of an overlap with perfume stores in what they carried. All of these products carried in perfume stores were luxury imports. Lapis and indigo - perhaps they were a source for artist's paints as well. Perfume stores and perfume workshops continued to work up until the last days of the Empire.

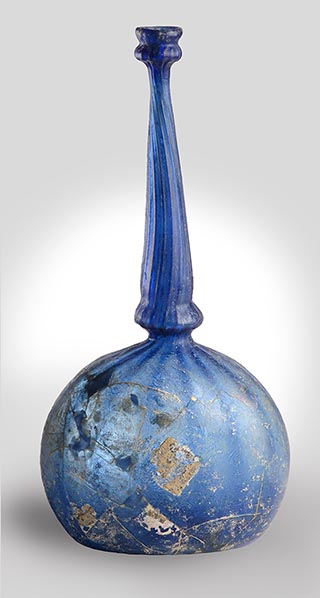

There are a number of delightfully pretty and sensual glass perfume bottles from Constantinople which have survived and are on display in museums. We have examples right up until the 15th century.

In March 1400 shop for the production and sale of perfumes - called a myrepsikon ergasteron - which was located near the Gate of Kynegos on the Golden Horn - was purchased by an aristocratic entrepreneur named Nicolas Sophianos for 200 hypera. A large tavern in the same district sold for the same amount - which gives you an idea of the scale of the perfumery. The location of the perfumery followed an old Byzantine tradition as it was located near the Blachernae Palace in the far northwest of the city. We know of other perfume workshops located near the Gate of St. John Prodromos on the Golden Horn from documents dated to 1340. The existence of so many perfume operations in the city infers two things - one, there was a ready supply of roses nearby, and two, a market to sell them in - the Byzantines still loved perfume. This area of the Golden Horn was host to Italian merchant colonies, so one can assume an export business of perfumes was taking place here. During the first Ottoman blockade of Constantinople around 1400 some nobles abandoned their estates and fled the city. From legal records we know of one such estate where the house was demolished and the lands converted to cultivation including grapes, wheat and roses by a nun named Petraleiphina. Thorny rose hedges were ideal boundaries to keep out the robbers and vandals who plagued the area.

There was an Imperial - Basilike - food market alongside the Golden Horn outside the seawall. It stretched from the Small Gate - Mikra Pyle - to the Imperial Gate - Basilike Pyle. Here you could buy all sorts of things; from fish, to cheese, caviar, preserved meats and fruit.

After 1453 the Ottomans continued the tradition of offering rose water for the washing of the hands when visiting the Sultan. Mehmet II had Hagia Sophia washed with rose water when it was converted to a mosque.

On the day before Constantinople fell to the Turks the people had made great wreathes and garlands of roses to adorn the Church of Theodosia, whose feast day was that Tuesday, May 29th. Certain types of roses, for example Rosa Coroneola, were grown by the Greeks and Romans to weave into crowns (coroneola) and garlands because the canes were flexible. The Church of Theodosia was most likely decorated with whatever roses were in season and available to them. Late May would have been the height of the season for roses in Constantinople.

On the day before Constantinople fell to the Turks the people had made great wreathes and garlands of roses to adorn the Church of Theodosia, whose feast day was that Tuesday, May 29th. Certain types of roses, for example Rosa Coroneola, were grown by the Greeks and Romans to weave into crowns (coroneola) and garlands because the canes were flexible. The Church of Theodosia was most likely decorated with whatever roses were in season and available to them. Late May would have been the height of the season for roses in Constantinople.

That's Saint Theodosia on the left in an ancient icon discovered in Saint Catherine's monastery in Sinai.

The following is from Alexander Van Millingen - Byzantine Churches in Constantinople - who tells us about the saint and her church:

"The saint is celebrated in ecclesiastical history for her opposition to the iconoclastic policy of Leo the Isaurian. For when that emperor commanded the icon of Christ over the Bronze Gate of the Great Palace to be removed, Theodosia, at the head of a band of women, rushed to the spot and overthrew the ladder up which the officer, charged with the execution of the imperial order, was climbing to reach the image. In the fall the officer was killed. Whereupon a rough soldier seized Theodosia, and dragging her to the forum of the Bous (Ak Serai), struck her dead by driving a ram's horn through her neck. Naturally, when the cause for which she sacrificed her life triumphed, she was honored as a martyr, and men said, 'The ram's horn, in killing thee, O Theodosia, appeared to thee a new Horn of Amalthea...."

"The shrine of S. Theodosia was famed for miraculous cures. Her horn of plenty was filled with gifts of healing. Twice a week, on Wednesdays and Fridays, according to Stephen of Novgorod, or on Mondays and Fridays, according to another pilgrim, the relics of the saint were carried in procession and laid upon sick and impotent folk. Those were days of high festival. All the approaches to the church were packed with men and women eager to witness the wonders performed. Patients representing almost every complaint to which human flesh is heir filled the court. Gifts of oil and money poured into the treasury; the church was a blaze of lighted tapers; the prayers were long; the chanting was loud. Meanwhile the sufferers were borne one after another to the sacred relics, 'and whoever was sick,' says the devout Stephen, 'was healed.' So profound was the impression caused by one of these cures in 1306, that Pachymeres considered it his duty, as the historian of his day, to record the wonder; and his example may be followed to furnish an illustration of the beliefs and usages which bulked largely in the religious life witnessed in the churches of Byzantine Constantinople."

The last Emperor, Constantine XI (there was a legend that the Last emperor was secretly buried in a pier of the church) and the Patriarch attended the last service here in honor of Saint Theodosia. The icons and the altar were also covered with roses. When the city fell the church was full of worshipers who had taken refuge there for protection. The Turks smashed their way into the church and massacred or enslaved everyone inside. The rose garlands were ripped from the church in search of hidden valuables, jewels on icons torn off, the holy images were smashed and the altar was desecrated. The holy relics - including those of Saint Theodosia - were destroyed. The body of Theodosia, preserved for 600 years in a jeweled, gilt silver reliquary was given to dogs to eat. A similar scene - on a much larger scale - was taking place in the great church of Hagia Sophia where perhaps 12,000 people had taken refuge. After the conquest the Church was converted into a mosque and was known as the "Mosque of the Roses".

Here is a reconstruction of what the church looked like in Byzantine times from the website Byzantium 1200. The facade of the church would have been plastered and painted, most likely with frescoes of saints and ornament, perhaps including roses. There is a rose that claims to have been brought from Constantinople by crusaders who sacked the city in 1204. "Uetersener Klosterrose", is an ancient rose that was found in an Cistercian monastery. After the Fourth Crusade the Latins occupied Constantinople for almost 70 years. The Byzantine monks were expelled and Latin ones moved into their monasteries. This rose was found by Cistercian monks, who brought it to Germany after the Greeks retook the city and the Latins fled. This rose was dedicated to the Virgin and grows like crazy - to 9 feet or more - without any of the diseases that plague modern roses. The Uetersener Monastery is in Schleswig-Holstein. Much of the loot taken by the crusaders from Constantinople ended up in Germany. Could this be a hedge rose of Constantinople? Here it is:

There is a rose that claims to have been brought from Constantinople by crusaders who sacked the city in 1204. "Uetersener Klosterrose", is an ancient rose that was found in an Cistercian monastery. After the Fourth Crusade the Latins occupied Constantinople for almost 70 years. The Byzantine monks were expelled and Latin ones moved into their monasteries. This rose was found by Cistercian monks, who brought it to Germany after the Greeks retook the city and the Latins fled. This rose was dedicated to the Virgin and grows like crazy - to 9 feet or more - without any of the diseases that plague modern roses. The Uetersener Monastery is in Schleswig-Holstein. Much of the loot taken by the crusaders from Constantinople ended up in Germany. Could this be a hedge rose of Constantinople? Here it is:

If you would like to buy the roses mentioned in this page click here.

If you would like to buy the roses mentioned in this page click here.

Part of this article was published in my blog on the Pallasart site on the Best Antique Roses for Your Austin Garden. It's here if you would like to read it.

click here for icons of christ

click here for icons of christ click here for icons of the theotokos

click here for icons of the theotokos click here for icons of angels

click here for icons of angels click here for icons of saints

click here for icons of saints