Emperor Nikephoros III Botaneiates

Augusta Maria of Alania

Archangel Gabriel

I have just watched a video of Robin Cormack on the DOAKS website where he describes how they got into the rooms, studied them and published their findings. Here is a transcript of what he said:

"We discussed what possibly I could do. It was agreed in Dumbarton Oaks that we could go there. The problem – so I worked with Ernest, and although previously when I’d seen Ernest he was officially working for Dumbarton Oaks, everything was organized so that there were problems in the Fethiye Djami in that when he asked the Turkish laborers to rebuild a wall, they would rebuild it in Ottoman style and not in Byzantine style and they had to take it down again and rebuild it. The problems with my work were quite different and so you have to contextualize this, that going to work in Hagia Sophia in the summer of 1973 meant we could not mention the word “Dumbarton Oaks.” We were given permission to work and used Underwood’s material, which I’d read, but in Istanbul we went to the director of Hagia Sophia and asked permission to look at the icons in the southwest rooms. We knew—Ernest knew—that the icons that were removed from Turkish immigrants in 1917 were stored in those rooms and that if we said that we were going to look at those, we’d actually confess what our plan really was. So I’m afraid it was a bit underhand. The director agreed we could work in the southwest rooms for two weeks and that we would be supervised by Şinasi Bey, who was an assistant, and that all our time would have to be with Şinasi as the commissar. We were perfectly happy with that except that Şinasi had a drink problem and tended to arrive late in the morning—we arrived at six in the morning and waited for him to arrive, any time between six and ten. And we also had to take him out to lunch. So Şinasi was both an essential part of our work but also made it slightly more difficult. We went into the southwest rooms, knowing that what we wanted to do was understand the sequence of the mosaics, describe them, and to clarify exactly what had happened to that part of St. Sophia, which was an addition to the building – of the original Justinian building. It was part of the picture of the palace. Şinasi was slightly surprised when we put up a scaffolding up to the height of the mosaics, but we said this was necessary to photograph the icons from the scaffolding—and of course we didn’t actually look at the icons at all in the two weeks. But, we just managed, working fast, to take enough photographs and to look in detail at everything in those rooms and we both felt at the end of that time that we had solved the secrets of the work in those rooms. And that we published and we felt that publication was archaeologically accurate and I don’t think it’s been challenged since; that was good. We hoped in that time to do work in the southwest buttress. The chapel had been photographed, and Ernest thought it eleventh century. Şinasi was unable to find the key and we never got into the southwest buttress. I’ve been in it another time, but I never got in that time, so that work we didn’t do.He and Ernst Hawkins were invited to the rooms to study and take photographs of a huge collection of icons that had been seized from Greek and Armenian refugees in 1917. These icons were to sold and they wanted pictures of them. I have seen them in Austin for auction. They got into the rooms and cleared stuff out, they got a scaffold in by telling the guards they needed it to take the pictures of the icons. They then studied the mosaics and found almost everything. They were not able to get into a chapel in the buttress with 9th Century mosaics - I have published a picture of this room on my Doors of Hagia Sophia page. Robin and Ernst published this report without the Turkish authorities ever knowing they had been in the hidden rooms of Hagia Sophia studying the mosaics. Had the Turks known they never would have been allowed in and we would know nothing about these mosaics."

Since then several Byzantinists led by Ken Dark have had access to at least some of these rooms and have taken photographs and he has discussed them in his recent book. It is impossible to tell whether the rooms are in the same condition when he saw them many years ago.

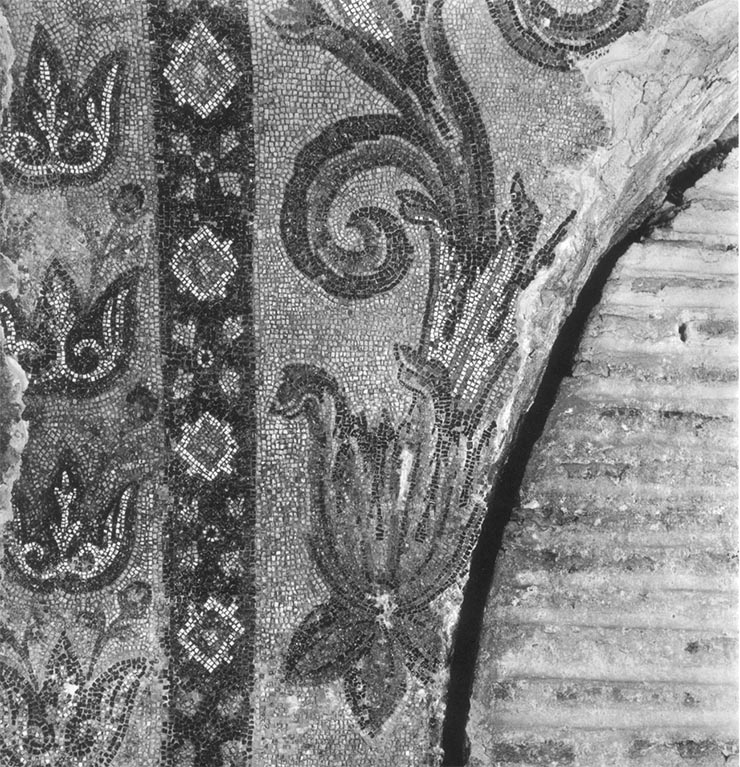

It is well known that fragmentary mosaics, never concealed by Islamic plaster or whitewash, still decorate the suite of rooms which lies behind the door at the south end of the west gallery of St. Sophia. These mosaics were the subject of two brief accounts by the late Paul A. Underwood, published on behalf of the Byzantine Institute, Inc. The first report appeared after a preliminary season of investigation (1950) in the rooms, and the second after conservation, cleaning, and photography was completed in 1954. Underwood also relied on observations made in these rooms when he came to discuss mosaic practices in Constantinople in his final publication of the Kariye Camii. These short presentations by Underwood immediately stimulated art-historical interest. The non-figurative mosaics attributed to the pre-iconoclastic period were used by Professor Ernst Kitzinger as a confirmation that the artists employed by Abd al-Malik to decorate the Dome of the Rock in 691-92 came from Constantinople. The figurative cycle attributed to a date after 843 was used by Professor Andre Grabar as evidence for a topical concern with theophanies in the ninth century in monumental art as well as in manuscript illustration. Meanwhile, a concise description of the mosaics became available in 1962 with the publication of the corpus of mosaics of St. Sophia put together by Professor Cyril Mango. Since he had in an earlier study already proposed an identification for the function of the rooms, Mango was able to propose on this basis a dating for the various periods of alteration to be observed. The aim of the present report is to assist the study of this area of the church by putting on record for the first time a full description of the mosaics. Our account is arranged according to an interpretation of the history of this part of the church, and an analysis of the structure to which they are attached precedes the discussion of the mosaics. This analysis of the indications of the masonry is necessarily detailed, though only those elements which affect the chronology are treated. We believe that such a chronology based on the material evidence is confirmed and refined by the identification of the rooms as a part of the Patriarchate of the Great Church.

The investigation in this area of St. Sophia was one of the first operations carried out by Underwood when he took over the direction of fieldwork by the Byzantine Institute on the death of its founder, Thomas Whittemore, in 1950. We were able to observe the mosaics and retake photographs in August 1973, and the present report incorporates the record made by Ernest Hawkins during conservation work between 1950 and 1952, as well as the uncompleted draft text which Underwood began in the 1950's. Since the work undertaken in the 1950's was limited to a consolidation of the mosaics and was not a full structural survey accompanied by a stripping of recent plaster overlays, our interpretations of the masonry evidence must be tentative and incomplete until such an investigation is carried out. In his Draft Report, Underwood recorded the friendly collaboration of the Department of Antiquities and the Museums of the Republic of Turkey and of two Directors of the Aya Sofya Muzesi during his work. In our turn, we can thank the present Director, Bay Hadi Altay, and Bay Sinasi Bagegmez for their help.

The investigation in this area of St. Sophia was one of the first operations carried out by Underwood when he took over the direction of fieldwork by the Byzantine Institute on the death of its founder, Thomas Whittemore, in 1950. We were able to observe the mosaics and retake photographs in August 1973, and the present report incorporates the record made by Ernest Hawkins during conservation work between 1950 and 1952, as well as the uncompleted draft text which Underwood began in the 1950's. Since the work undertaken in the 1950's was limited to a consolidation of the mosaics and was not a full structural survey accompanied by a stripping of recent plaster overlays, our interpretations of the masonry evidence must be tentative and incomplete until such an investigation is carried out. In his Draft Report, Underwood recorded the friendly collaboration of the Department of Antiquities and the Museums of the Republic of Turkey and of two Directors of the Aya Sofya Muzesi during his work. In our turn, we can thank the present Director, Bay Hadi Altay, and Bay Sinasi Bagegmez for their help.

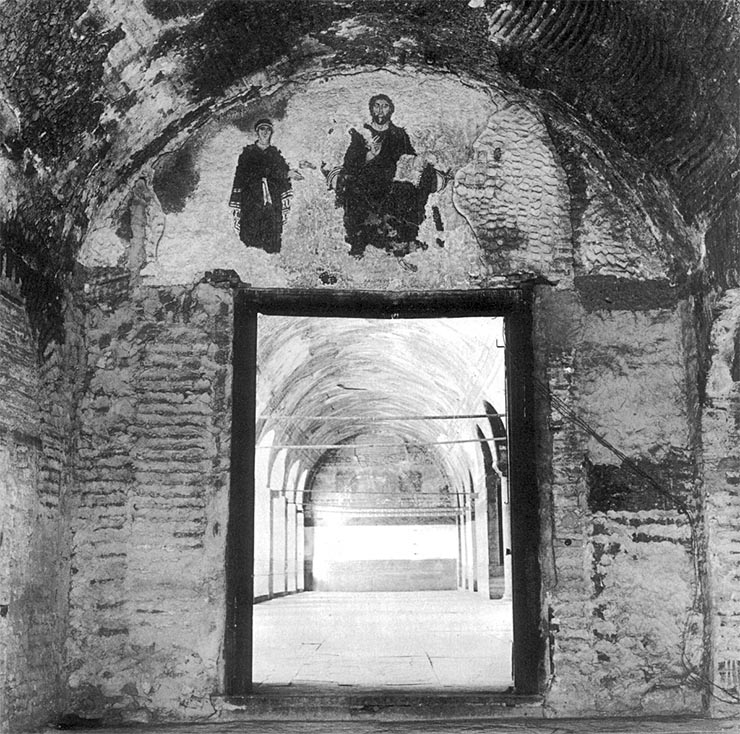

The suite of rooms decorated with mosaics can today be entered only through the doorway at the south end of the west gallery of St. Sophia This door opens directly into a long and relatively low room which is the largest room of the suite and lies immediately above the entrance vestibule to the inner narthex at the southwest corner of the church, the present means of access for the public. The dimensions of the room above the southwest vestibule nearly coincide with it in length and breadth. In this report we shall refer to it as the Room Over the Vestibule. Smaller rooms lie to the east and west of it, but the three to the west lack decoration and their structure was disturbed when Sinan raised the southwest minaret (around 1573), not to mention alterations undertaken during the Fossati restorations. Present access to these rooms is through a marble doorway at the south end of the Room Over the Vestibule. Facing this Byzantine doorway, in the east wall of the Room Over the Vestibule, is a crude rectangular opening, which has become the only entrance to a high room, nearly square in plan, and surmounting the southwest ramp that climbs from ground level to the gallery of St. Sophia. We shall call this the Room Over the Ramp. A small square room is now reached only through an archway at the northwest corner of the Room Over the Ramp. Since we must distinguish this space as a separate architectural unit, we shall refer to it as the Alcove. These three units are important because in them mosaic decoration has survived in a fragmentary state.

It is difficult for the viewer of these mosaics to recreate their original setting, not the least because of the deterioration in the conditions of lighting.![]()

The two large rooms are each lit today only by a pair of small rectangular windows in their south walls. These clumsy windows are visible on the exterior to the visitor who approaches St. Sophia from the south, and our illustrations of this view were photographed in the winter of 1936-37 when parts of the wall of the church were being stripped of plaster. These small windows were made up of the marble plaques of the former Byzantine windows, and were already in position by 1786, when a view of St. Sophia was made for Sir Richard Worseley. The various changes to the structure of the rooms are the result of remodeling and maintenance work during the Byzantine period and of later consolidation during the Ottoman period. Due to settlement or other movement the structure of the southwest ramp tower seems to have caused continual trouble. At the time of the Fossati restoration of the mosque the rooms were in use for storage and were inaccessible to visitors (a circumstance which has not changed). Antoniades, for instance, had to derive his description and plan from Salzenberg (hence their agreements in error concerning the form of the vaulting of the Room Over the Vestibule and on the placing of doors). Salzenberg gained his information during his observations of the Fossati operations while he was on the spot between January and May 1848. If his record is reliable, marble revetment was then still in position, at least on the walls of the Room Over the Vestibule. Undoubtedly the vertical walls of the rooms were originally faced with marble revetment, for the attachments remain visible. Perhaps the squalid appearance of the rooms at that time (graphically described by Murav'ev in 1849) had induced the Fossati to ransack the marble; this may partly explain their success in replacing missing slabs in the lateral aisles and galleries of St. Sophia without the supply of any new marble. This suggestion seems to be supported by their drawing of the south wall of the Room Over the Ramp. On the left of this sheet is a careful watercolor copy of part of the vault mosaic which can be seen to have been more fully preserved at that time than it is now. On the right side of the sheet the drawing of the south wall is admittedly a less careful rendering of the evidence. However, since a record could at that time be made of the capital and column shaft between the central and western pointed arches and since both column and shaft were entirely submerged in a rubble fill by 1950, the obvious deduction is that it was the Fossati who reinforced this opening. Moreover, in this fill, at a height of 2.25 m. in the southeast corner, we found the date 1849 incised with a trowel point into the mortar. Similar untidy pink mortar is visible in the extensive areas of repointing in the rooms, and can therefore be attributed to a campaign of consolidation undertaken after the removal of the marble revetment and carried out in the last months of the Fossati restoration, which was substantially completed by 13 July 1849.

This removal of the revetment no doubt revealed alarming cracks and deterioration in the brickwork. One area of particular concern, to judge from the quantity of pink mortar, was the south section of the party wall which divides the Room Over the Ramp from the Room Over the Vestibule. The trouble here was caused by the movement outward of the south wall of the Room Over the Ramp. Remedial repairs were carried out in the brickwork of the party wall in the area of the present rectangular door opening between the two rooms. The brick lintel of this doorway, bound in position by metal struts, may be attributed to Fossati activity. To judge from the lines of cracking in the brickwork above this opening (on both the east and west faces of the wall), the Fossati replaced a brick arch here over the doorway; this would have had an extrados at the same height as that above the Byzantine door opposite in the west wall of the Room Over the Vestibule. We suggest that there was a doorway in the south section of the party wall.

The building of the southwest vestibule and the suite of rooms above it was a major alteration to this corner of St. Sophia. It probably caused the change in function of the Augustaion from that of an agora in the time of Justinian to a courtyard of St. Sophia by the time of Constantine Porphyrogenitos. The material evidence of the structure of the rooms suggests that this major conversion took place not long after the completion of St. Sophia and probably in the sixth century, but it does not provide a decisive solution to the problem of their date and function. The most probable answer is given by a consideration of the written sources for the history of the Great Church, and, finally, by the nature of the mosaic decoration itself. The documentary evidence can now be outlined.

The unambiguous evidence of a number of primary sources is that the area between St. Sophia and the Augustaion was occupied by the Palace of the Patriarch of the Great Church. This palace, like the Great Palace of the Emperors, sprawled out over a considerable area; additions and alterations are recorded from the seventh century, starting with the Thomaites of 607-10, to the thirteenth century. The major apartments of this palace are said to have been not at ground level but in the safety of an upper storey, a practice which seems general for medieval episcopal palaces. In the accounts of the Russian pilgrims to St. Sophia in the Palaeologan period, the door of the southwest ramp in the vestibule is mentioned as the entrance to the Patriarchal Palace. The second door to the ramp, that in its south side, may be suggested as the side door inside which St. Theodore of Sykeon was induced to bless the childless daughter of a deacon Sergios and her husband when he came down from an audience with Patriarch Kyriakos, sometime between 596 and 602.

In view of the location of the Patriarchate and the function of the ramp as its staircase (according to post-Justinianic texts), we have no hesitation in identifying the gallery-level rooms as one part of this Patriarchate. More specifically, we accept the suggestion, made by Cyril Mango, that from their position directly off the gallery of the church and from the nature of their mosaic decoration the rooms can be identified: the Room Over the Vestibule is the Large Sekreton,and the Room Over the Ramp is the Small Sekreton. Mango likewise suggested that the nucleus of the Patriarchate and the Sekreta were built by Patriarch John III Scholasticus (565-77): in a “magnificent manner," according to the contemporary Syriac historian, John of Ephesus. There is no reason to doubt the reliability of this sixth-century witness, but the text does raise a difficulty. It reports that the palace was rebuilt after it had been destroyed by fire. Mango presumed this to be the fire during the Nika Riot of 532, and, in this, he is followed by Pasadaios, but they fail to account for the place where patriarchal business was carried out in the interim period. Where, in particular, did the Second Council of Constantinople convene for its sessions in May 553? According to a recent commentary, the 168 bishops met on 5 May 553 in the Large Sekreton. If this were the case, then our identification would be ruled out for two reasons: dating and size. The source of information about this Council happens to be not the Greek Acts, which are lost, but two Latin versions, of which the longer specifies the meeting-place. The delegates sat in "secretario venerabilibus Episcopis huius regiae civitatis" It is therefore unwarranted to specify the use on this occasion of the Large Sekreton; it is equally clear that the patriarch at this time did not lack official apartments. One solution for the location of these offices would be to accept the hypothesis that the site of the Patriarchate in the period before Justinian was more closely attached to the church of St. Eirene and lay to the north of St. Sophia, and to suggest its rebuilding on the same site soon after 532. In this case there would be little doubt that the fire mentioned by John of Ephesus was the serious one of December 563 which completely destroyed the Xenon of Sampson (as already rebuilt after 532 by Justinian), houses in front of it, the atrium near the Great Church known as the the two monasteries near St. Eirene, and the atrium of St. Eirene and part of its narthex. The main objection to this hypothesis is the silence in these sources about patriarchal buildings, which could be explained if they were indeed very limited in extent or, alternatively, simply omitted. Perhaps it is simpler to suppose the Patriarchate was elsewhere. In either case, the large fire of 563, shortly before the election of John III Scholasticus, was the most likely justification for the aggrandizement of the Patriarchate.

Financial support for an architectural addition to St. Sophia from the Emperor to the Patriarch seems likely, and the adornment of St. Sophia by Justin II (565-78), recorded by Theophanes, may refer to the building of the new Patriarchate. This text gives Justin's motive as piety, and if by this is meant filial piety, or the need for Justin to legitimize his succession, by means of the maintenance of Justinian's foundations, then a date early in his reign is indicated. A relatively early time in the period of office of John III Scholasticus could be entertained on different grounds. According to Payne Smith, the patriarchal court used by John Scholasticus during the persecution of Monophysite bishops was described by John of Ephesus as the Sekreton. This persecution began about three years before the Patriarch's death on 31 August 577, and so the Palace was in use at least by 574. In summary, the archeological evidence of a substantial alteration at the southwest corner of St. Sophia at some period in the sixth century may be correlated with documentary records of the erection of the Patriarchal Palace between 565 and 577.

The Room Over the Vestibule has lost all traces of its original decoration. Its present mosaics, which survive only in a few fragmentary areas, are the product of a single campaign. A description of their architectural setting was published by Underwood, but needs a brief comment. The two south bays have rebuilt vaults. While these give the same effect of a barrel vault as in the original north bay, they are slightly domed along their ridge, and the bricks are laid in the manner of groin vaults with the groins flattened out. Where these vaults meet the walls a concave lunette is formed on each side of the bay, and the mosaicists took account of these four lunettes in planning the cycle.

The south window was remodeled at the same time as the vaults, but the structural antae of the earlier opening were left in position. The new window was apparently modeled on the type found in the west gallery, but the details are now obscured by the Turkish fill of rubble. Probably it consisted of a screen of two orders of superimposed mullions, the spaces in between being filled by glazed grilles and marble balustrades. The two mullions of the upper zone are visible (the right one is rough and cracked), and in the left window a fragment of an oak grille was found with mortices for horizontal and vertical struts. The new window was not aligned with the faces of the antae, but was set back, and the side windows are not of the same size and shape. No continuous horizontal element between the two zones can at present be observed, but perhaps tie beams were used. From the lower zones the marble plaques are preserved as the frames of the rectangular Turkish windows, and a part of the capital of the right mullion can be seen in the fill. The plaques match those in the Room Over the Ramp (both sets, for example, have a similar decoration of a cross in relief); presumably those here were taken from the original south opening, set aside, and reused. The capital in the fill, about 64 cm. in width, below an abacus of 75 cm., appears to be of a fifth-century Corinthian type. It, too, must be a reused element, though because it differs from the capital in the Room Over the Ramp it is difficult to say where it was first used. It must be said that the remodeling of the south window lacks finesse.

All the vaults received mosaic decoration, but none of it remains in the north bay, where only the traces of the spud work of the first layer of plaster confirm the previous existence of mosaic work here also. The scheme of the other two vault bays can be recognized; on each side of a border running along the axis of the Room two superimposed registers of figures were set out-full-length standing figures above, and bust figures below. The eastern and western sides of the vaults are therefore decorated in two symmetrical halves. On the north tympanum, over the door which is the entrance from the Room into the west gallery of St. Sophia, is a semicircular lunette panel.

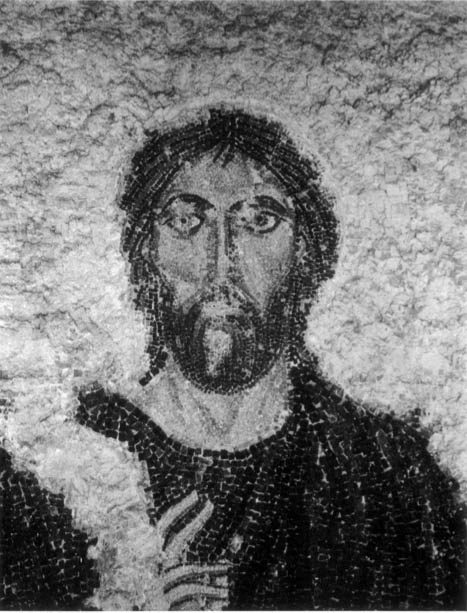

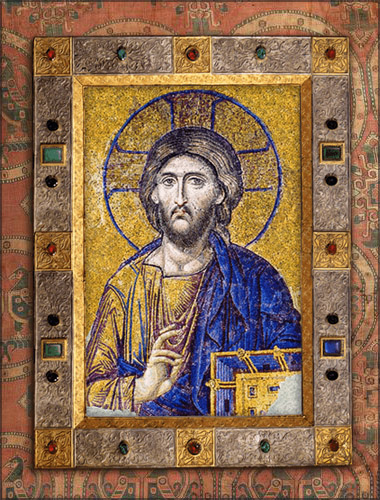

The composition here was the "Deesis," with the Virgin and John the Baptist on either side of an enthroned Christ. The mosaics are described below in hierarchical order of their iconography, southward from the door, to conform with the preliminary account of Underwood, but we shall not use his lettering for the various patches of mosaic.

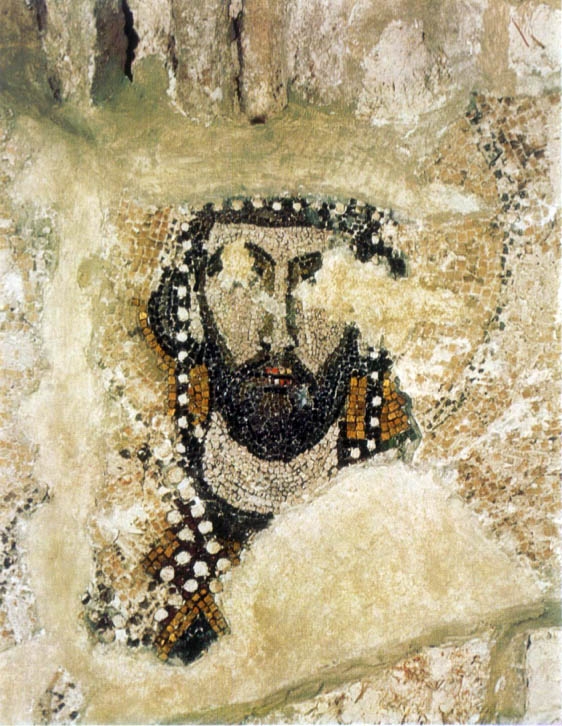

The Room Over the Vestibule was decorated in its two southern bays with representations in the lower zone of the twelve Apostles and four Patriarchs of Constantinople; the upper zone seems to have the space for about twenty standing figures. The inclusion of St. Methodios in the cycle dates its execution after his death in 847. The scheme might seem to be a typical example of the manner of representing the Heavenly Cosmos through portraits of saints, which has been claimed to be characteristic of the art of the second half of the ninth century. It can be doubted, however, whether this is a well-founded characterization - the evidence for it is meager: literary descriptions of churches, now lost and of unknown size, may not give full details of the decoration. St. Sophia is a special case and the church of the Holy Apostles does not seem to conform. Moreover, the cycle of the Room Over the Vestibule is not strictly a church decoration, so the nature of its program is not a sure guide to its dating. The perennial theme of decorations in the Patriarchal Palace was the representation of Orthodoxy. John III Scholasticus, Eutychios, and Nicetas have already been mentioned as patriarchs who used art to proclaim their theological beliefs. The Russian pilgrim Antony of Novgorod records that around 1200 portraits of all the patriarchs and emperors, accompanied by an indication whether they were orthodox or heretical, were displayed in St. Sophia. While the meaning in this passage is possibly "in the gallery," Antony elsewhere uses the noun indiscriminately to refer to the gallery or to the Patriarchal Palace. Grabar has speculated that the patriarchs may have maintained a picture gallery of their predecessors in their Palace. In the case of our cycle, its underlying theme is most likely to be the portrayal of the orthodox theology of its sponsor. If anywhere in Byzantine religious art, a decoration in the Patriarchal Palace ought to exemplify the way in which topical reasoning could be translated into a general frame of reference.

The Room Over the Vestibule was decorated in its two southern bays with representations in the lower zone of the twelve Apostles and four Patriarchs of Constantinople; the upper zone seems to have the space for about twenty standing figures. The inclusion of St. Methodios in the cycle dates its execution after his death in 847. The scheme might seem to be a typical example of the manner of representing the Heavenly Cosmos through portraits of saints, which has been claimed to be characteristic of the art of the second half of the ninth century. It can be doubted, however, whether this is a well-founded characterization - the evidence for it is meager: literary descriptions of churches, now lost and of unknown size, may not give full details of the decoration. St. Sophia is a special case and the church of the Holy Apostles does not seem to conform. Moreover, the cycle of the Room Over the Vestibule is not strictly a church decoration, so the nature of its program is not a sure guide to its dating. The perennial theme of decorations in the Patriarchal Palace was the representation of Orthodoxy. John III Scholasticus, Eutychios, and Nicetas have already been mentioned as patriarchs who used art to proclaim their theological beliefs. The Russian pilgrim Antony of Novgorod records that around 1200 portraits of all the patriarchs and emperors, accompanied by an indication whether they were orthodox or heretical, were displayed in St. Sophia. While the meaning in this passage is possibly "in the gallery," Antony elsewhere uses the noun indiscriminately to refer to the gallery or to the Patriarchal Palace. Grabar has speculated that the patriarchs may have maintained a picture gallery of their predecessors in their Palace. In the case of our cycle, its underlying theme is most likely to be the portrayal of the orthodox theology of its sponsor. If anywhere in Byzantine religious art, a decoration in the Patriarchal Palace ought to exemplify the way in which topical reasoning could be translated into a general frame of reference.

The inclusion of the four patriarchs intimately involved in fighting the iconoclastic heresy must be significant for dating the Room. It is true that the four appear as a separate group in the diptychs of the Synodikon of Orthodoxy, which were recited annually from the ninth century onward,109 but their selection and prominence in the decoration must have some topical significance and can only indicate an active concern with Iconoclasm on the part of the planner of the mosaics. For how long after the death of Methodios was Iconoclasm a live issue in the Patriarchal Palace? In a recent examination of this question, Mango has suggested an almost obsessive concern with Iconoclasm by Photios during his first period in office as patriarch (858-67), at a time when the threat of its renewal must already have passed. On the basis of this view, the early 860's are a likely time for the mosaics of the Room Over the Vestibule. The dismissal of Photios in 867 did not, however, banish the issue of Iconoclasm from the Patriarchate. The Fourth Council of Constantinople in 869/70 reveals some concern with Iconoclasm on the part of Ignatios, even if it was not at the top of the agenda as at the Photian Council of 861. In the second part of the eighth session (November 869) the subject was the problem of the recalcitrant iconoclast, Theodore Krithinos, and his partisans. Krithinos, who was a former archbishop of Syracuse, refused to compromise and was condemned, but some of his partisans, Nicetas, Theophilos, and Theophanes, agreed to make a confession of their mistakes in front of the delegates. The session ended with the pronouncement of eighteen anathemas against iconoclasts. When the canons were drawn up on 28 February 870, the third was directed against Iconoclasm. It included a novel formulation that icons are justified since without them a Christian soul would be in danger of being unable to recognize his God."' By 879 the intellectual climate was such that the canons of the Photian Council only repeated the earlier formulations, while for Arethas interest in Iconoclasm was academic.

The implication of the program is, therefore, a dating within a fairly short period in the ninth century, not earlier than 847 and not later than the 870's. Such a date would also limit the sponsoring Patriarch to one of two candidates, either Ignatios or Photios. The question might therefore be approached through an investigation of the mentality and artistic patronage of these well documented figures;1 but for the present we shall consider the issue through the art historical evidence. The dating bracket proposed on the basis of the program is harmonious with the style. Underwood attributed the mosaics to the second half of the ninth century, while Mango and Hawkins have gone on record with the suggestion of the 850's or 860's.

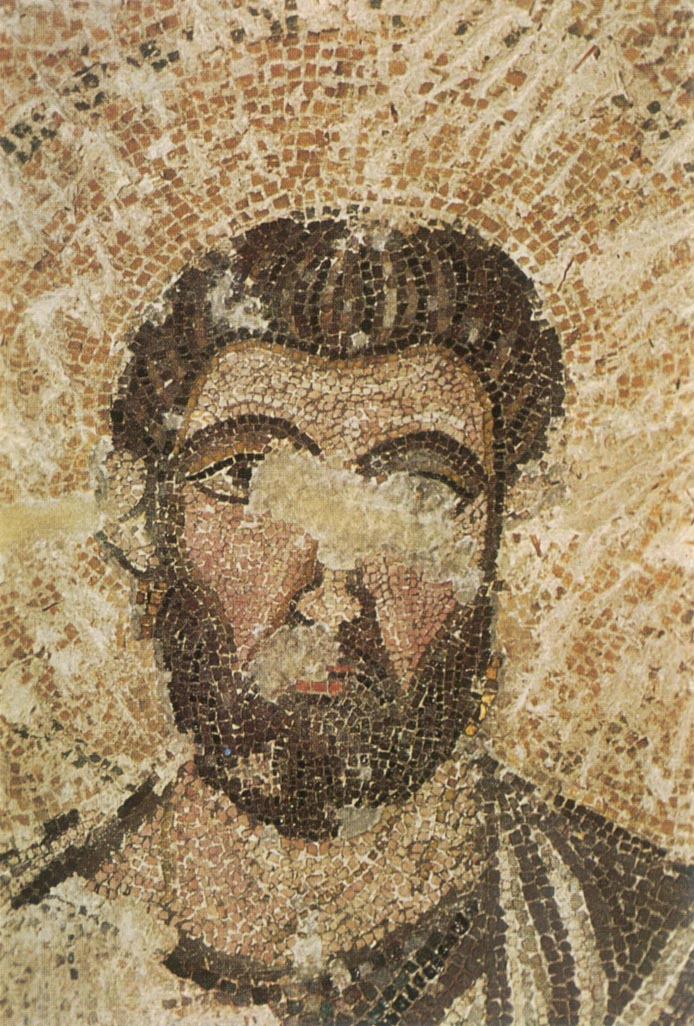

Comparisons with other ninth-century mosaics help to clarify the stylistic trend of the homogeneous cycle of the Room Over the Ramp. There is little point of contact with the techniques and coloring used by the mosaicists who replaced the sanctuary figures of the church of the Koimesis at Nicaea. A comparison with the cupola mosaics of the church of St. Sophia in Thessaloniki, which can be attributed to 885, produces quite positive results. Certain workshop methods of modeling used in the Room Over the Vestibule can be recognized in Thessaloniki, but in a more extreme and mannered form. Thus, the pear shapes in the drapery over the knees of Christ and the Virgin or the hanging zigzag folds of the Virgin's maphorion have become more emphatic, more schematic, altogether more dominant elements at Thessaloniki - signs of a relatively later date of execution. The mask-like face and the pattern of the drapery of the standing Virgin at Thessaloniki owes a distinct debt to our Virgin of the Deesis. To devote further attention to the developments in color and line, through which the impressive impact of the later cupola figures is made on the spectator with a different effect from the more intimate groups of the Room Over the Vestibule, is unnecessary for the present purpose of the comparison. The cupola at Thessaloniki is a part of the cathedral church of the city, and was commissioned by archbishop Paul, a personal supporter of Photios appointed in 880. His mosaicists, who must have been trained in Constantinople, had perhaps previously been employed by the Patriarch.

Although the comparison with Thessaloniki might be taken to point to a date not too much before 885, the means to a more precise decision is offered by stylistic parallels in certain mosaics of St. Sophia itself, and in manuscripts produced in the orbit of the Great Church. 7 The second half of the ninth century was a period offering fairly permanent employment for artists in Constantinople, and one would expect to find a variety of styles in the works which survive. The most specific comparison with the Room Over the Vestibule is the tympanum mosaics of the naos; in particular, the massive treatment of figures (consider Christ and St. Simon Zelotes), the modeling of some garments in light-colored stone tesserae with folds in dark lines (often the lines are short and terminate in hooks), the fairly loose disposition of tesserae, and the use of greens for shadowing flesh. The way in which such features were treated in the north tympanum mosaics seemed to Mango and Hawkins to belong to the last two decades of the ninth century, being shared to some extent by the narthex panel and the Alexander mosaic of the north gallery. In their estimation, the mosaics of the Room Over the Vestibule belonged to an earlier stage, at a cruder level of achievement, with relatively clumsy figures too heavily outlined, and with too abrupt transitions from light to shade. They therefore proposed a date earlier than or contemporary with the sanctuary vault mosaics of St. Sophia, and saw their interest to lie in the existence of a different "style" coexisting with that of the apse.

If the mosaics of the Room Over the Vestibule are treated as a part of the total ninth-century scheme of St. Sophia, this assessment of Mango and Hawkins might be modified in the light of our description. Can these mosaics be earlier than the apse of St. Sophia? When Photios inaugurated the present apse mosaics on 29 March 867, he proclaimed the church stripped of decoration. Even allowing for the hyperbole permitted on a state occasion, it is difficult to account for his words if the Room Over the Vestibule had recently been redecorated with a figurative cycle. If the assumption is made that at the time of the homily the Patriarchal rooms lacked this cycle, then the rhetoric of Photios becomes more credible, and, moreover, it can be presumed that his reference to the visual mysteries of the church being scraped off had a specific source in the documentary reports of the iconoclasm of Nicetas in the Patriarchal Palace.

The relevance of the cycle of the Room Over the Vestibule to the planning of the tympana also needs comment. Mango and Hawkins correctly state that the choice of the bishops shows no special emphasis on the suppression of Iconoclasm, but from this they infer that, at the time of planning, Iconoclasm had lost much of its urgency. An alternative explanation is that our cycle was close in time, but earlier, and so it was thought otiose to repeat its message in the naos. On this line of reasoning the date proposed for the tympana might be a little too late, and these mosaics may belong to the late 870's. The execution of the lowest register must date after the death of Ignatios in 877, but, if the redecoration of the tympana was indeed made necessary by the earthquake of 869, as argued by Mainstone, then it might have been planned in the 870's.

The decoration of the Room Over the Vestibule is conceivable as an integral part of a scheme in St. Sophia developed in the decade after 867. A date fairly close to that of the Church Fathers of the north tympanum is likely, for the differences between the two groups should not be overstressed. Photographs of the mosaics of the Room Over the Vestibule exaggerate the harsh- ness of the modeling and of the transitions from light to shadow. In reality, these two sets of mosaics are closer to each other than either is to the narthex panel. No greater contrast in the treatment of heads occurs in the Macedonian period mosaics of St. Sophia than between the relatively soft modeling of Christ in the Room Over the Vestibule and the broad manner of the narthex Christ, where the face is built up on contrasts in groups of colored tesserae. The major difference between the Room Over the Vestibule and the tympana is in the handling of color. In extreme contrast to the limited range of colors of the generally pale and opaque tonality of the Church Fathers, the earlier figures fill with glittering pools of color a room which must have always been fairly dark and frequently lit by candles. This interest in color relates the Room to the apse mosaics of St. Sophia, and it also influenced the later cupola mosaics of St. Sophia in Thessaloniki.

The mosaics of the Room Over the Vestibule are best regarded as a stylistic bridge between the apse and tympana of St. Sophia rather than as a separate mode. The most significant difference is not in style so much as in quality. The striking homogeneity of the mosaics in the Room is confirmation that they belong to a single campaign of work, but there is another side to this conformity. The work is vigorous, yet somehow stereotyped and routine in its production. Such a judgment of its quality assists in a comparison of the Virgin of the Deesis with the Virgin in the apse. They differ in scale and position, but in the faces the modeling and color and treatment of the flow of the tesserae are similar. This can more easily be recognized when allowance is made for the weakness of the mosaicist of the Deesis. Of course, it is not surprising to see such refinement and power in the apse, which represents one of the most important commissions of the Middle Ages.

Certain historical conditions are relevant to a dating of the mosaics of the Room Over the Vestibule, if a time after March 867 is to be upheld. Photios, in the seventeenth Homily delivered on 29 March 867, concluded with an appeal to the two Emperors for their patronage of further figurative art in St. Sophia. The political and ecclesiastical intrigues of that summer can hardly have been conducive to the arrangement of such works. The last week of September saw the assassination of Michael III (23-24 September) and the removal of Photios (25 September). The recall of Ignatios did not immediately terminate the protracted communications with the Papal court. Then, from 9 January 869, St. Sophia suffered earthquake damage for forty days, which was sufficient to induce Basil I to provide funds for repairs. However, the sessions of the Fourth Council could have been held in the south gallery of St. Sophia from October 869 to February 870. The 870's were years of relative calm, with more opportunity for artistic patronage. It was a decade of high density of mosaic production, during which the major documented commissions were SS. Sergios and Bacchos, the Virgin of Pege, and the Holy Apostles, and the Nea Church of Basil I; the situation might even be taken to support statistically the higher probability of the execution of our mosaics in the 870's. Possible indications of date are offered by the internal evidence of the mosaics themselves. Two points of detail in the iconography deserve highlighting. The first is the portrait of St. Constantine, which should be contrasted with his representation in the lunette panel in the vestibule below. The differences are not limited to style; the iconographic type is different, our mosaic being distinguished by the dark bushy beard. The use of two types ought to correspond to a difference of intention. The meaning of the vestibule panel lies in its public claim of protection offered to city and church by the Virgin and Child. For this context Constantine appears more as a type of the young heroic saint than as an emperor. In the Room Over the Vestibule Constantine takes on the appearance of a contemporary Byzantine emperor and, moreover, bears a striking resemblance to a member of the family.

Excerpts From The Mosaics of St. Sophia at Istanbul: The Rooms above the Southwest Vestibule and Ramp - by the great Robin Cormack (he is married to Mary Beard) and Ernest J. W. Hawkins

Bob Atchison

click here for icons of christ

click here for icons of christ click here for icons of the theotokos

click here for icons of the theotokos click here for icons of angels

click here for icons of angels click here for icons of saints

click here for icons of saints