From O City of Byzantium by Niketas Choniates

The assembly, lamenting at his words, gladly received Manuel as emperor as though he were appointed by lot or election. Afterwards, the father, after addressing his son and giving him sound advice, crowned him with the imperial fillet and put on him the purple-bordered paludamentum. Then the troops were assembled, and they proclaimed Manuel emperor of the Romans, and each of the nobles, with his retinue standing apart, loudly acclaimed the new sovereign. Thereupon, when the Holy Scriptures had been brought forth, everyone he assembly, lamenting at his words, gladly received Manuel as emperor as though he were appointed by lot or election. Afterwards, the father, after addressing his son and giving him sound advice, crowned him with the imperial fillet and put on him the purple-bordered paludamentum. Then the troops were assembled, and they proclaimed Manuel emperor of the Romans, and each of the nobles, with his retinue standing apart, loudly acclaimed the new sovereign. Thereupon, when the Holy Scriptures had been brought forth, everyone confirmed on them his goodwill and loyalty to Manuel. The initiator and celebrant of these ceremonies was the grand domestic, whose intention was to dissolve and dissipate the attempts at disturbance and rebellion by the ambitious and to blunt the assistance given by a good many to several of the emperor's kin, who, putting forth seniority of birth as a great and venerable tradition and magnifying their connection to the imperial family through marriage, deemed themselves more worthy to rule the empire.

The assembly, lamenting at his words, gladly received Manuel as emperor as though he were appointed by lot or election. Afterwards, the father, after addressing his son and giving him sound advice, crowned him with the imperial fillet and put on him the purple-bordered paludamentum. Then the troops were assembled, and they proclaimed Manuel emperor of the Romans, and each of the nobles, with his retinue standing apart, loudly acclaimed the new sovereign. Thereupon, when the Holy Scriptures had been brought forth, everyone he assembly, lamenting at his words, gladly received Manuel as emperor as though he were appointed by lot or election. Afterwards, the father, after addressing his son and giving him sound advice, crowned him with the imperial fillet and put on him the purple-bordered paludamentum. Then the troops were assembled, and they proclaimed Manuel emperor of the Romans, and each of the nobles, with his retinue standing apart, loudly acclaimed the new sovereign. Thereupon, when the Holy Scriptures had been brought forth, everyone confirmed on them his goodwill and loyalty to Manuel. The initiator and celebrant of these ceremonies was the grand domestic, whose intention was to dissolve and dissipate the attempts at disturbance and rebellion by the ambitious and to blunt the assistance given by a good many to several of the emperor's kin, who, putting forth seniority of birth as a great and venerable tradition and magnifying their connection to the imperial family through marriage, deemed themselves more worthy to rule the empire.

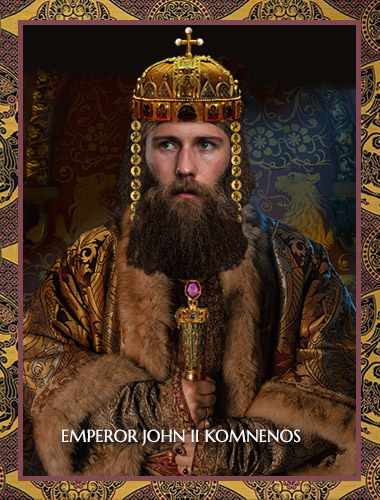

Several days after these events, Emperor John departed this life, having reigned twenty-four years and eight months [15 August 1118 - 8 April 1143]. He had governed the empire most excellently, and his life was well pleasing to God; in moral character he was neither dissolute nor incontinent; by way of gifts and expenditures he pursued magnificence, as is evidenced by his frequent distributions of gold coins to the City's inhabitants and by the many beautiful and large churches he built from their foundations. More than all others, he was a lover of glory, and, he was so fastidious as to the decorum and deportment of the members of his family that he would inspect the cut of their hair and carefully scrutinize the shoes on their feet to see if the leather had been sewn to the exact shape of the foot. He swept the palace clean of idle and filthy conversation during public audiences, of profligacy in food and dress, and of all else that was ruinous and destructive of life; playing the role of grave chastiser and desiring that his attendants should emulate him, he never stopped in the pursuit of every virtue. I do not mean that by behaving in this fashion he was lacking in the graces, inscrutable, inaccessible, sullen in appearance, knitted-browed, or even wrathful. He presented himself to public view as a model of every noble action, and when enjoying a respite from public matters, he would avoid the commotion of large crowds, turning a deaf ear to their babbling and jabbering; his speech was dignified and elegant, but he did not spurn repartee or in any way hold back and stifle laughter. He only just failed to reach the very summit of self-control and steadfastness and barely escaped the charge of parsimony; depriving no one of life nor inflicting bodily injury of any kind throughout his entire reign, he has been deemed praiseworthy by all, even to our own he crowning glory, so to speak, of the Komnenian dynasty to sit on the Roman throne, and one might well say that he equaled some of the best emperors of the past and surpassed the others.

Several days after these events, Emperor John departed this life, having reigned twenty-four years and eight months [15 August 1118 - 8 April 1143]. He had governed the empire most excellently, and his life was well pleasing to God; in moral character he was neither dissolute nor incontinent; by way of gifts and expenditures he pursued magnificence, as is evidenced by his frequent distributions of gold coins to the City's inhabitants and by the many beautiful and large churches he built from their foundations. More than all others, he was a lover of glory, and, he was so fastidious as to the decorum and deportment of the members of his family that he would inspect the cut of their hair and carefully scrutinize the shoes on their feet to see if the leather had been sewn to the exact shape of the foot. He swept the palace clean of idle and filthy conversation during public audiences, of profligacy in food and dress, and of all else that was ruinous and destructive of life; playing the role of grave chastiser and desiring that his attendants should emulate him, he never stopped in the pursuit of every virtue. I do not mean that by behaving in this fashion he was lacking in the graces, inscrutable, inaccessible, sullen in appearance, knitted-browed, or even wrathful. He presented himself to public view as a model of every noble action, and when enjoying a respite from public matters, he would avoid the commotion of large crowds, turning a deaf ear to their babbling and jabbering; his speech was dignified and elegant, but he did not spurn repartee or in any way hold back and stifle laughter. He only just failed to reach the very summit of self-control and steadfastness and barely escaped the charge of parsimony; depriving no one of life nor inflicting bodily injury of any kind throughout his entire reign, he has been deemed praiseworthy by all, even to our own he crowning glory, so to speak, of the Komnenian dynasty to sit on the Roman throne, and one might well say that he equaled some of the best emperors of the past and surpassed the others.

As soon as he was proclaimed emperor [5 April 1143], Manuel dispatched forthwith to the queen of cities the grand domestic John Axuch, together with the chartoularios Basil Tzintziloukes, to make arrangements for the smooth transfer of power to the new regime and to pave the way for his entry with appropriate festivities. Moreover, they were to constrain his brother, the sebastokrator Isaakios. The emperor was apprehensive lest Isaakios, on being informed that his father was dead and that the scepter had been given to his younger brother, should form a party of opposition and hotly contend to make himself master of all, inasmuch as he was in line to succeed the throne and happened, at that moment, to be present in the queen of cities and lodged in the palace, where piles of money were stored and the imperial vestments were kept.

<John, therefore, entered the City in great haste, and since Isaakios had not yet been apprised of events, seized him and incarcerated him in the Pantokrator monastery built by Emperor John."' Learning of his father's death and his brother's accession after his arrest, Isaakios, powerless to do anything, complained that he had been made to suffer beyond all measure and extolled the order by which the whole universe is sustained. "Alexios," he said, "the firstborn of my brothers and heir to the paternal throne, quitted this world, having succumbed to Death; he was followed by Andronikos, the second-born, who departed this life shortly after returning with his brother's corpse from across the sea." Isaakios coveted the throne for himself, insisting that he was the rightful sovereign.

But in vain did he tragically declaim such sentiments, and for naught did he flutter his wings like a little snared bird. The grand domestic took charge of the palace guard and attended to the acclamation of Emperor Manuel on the part of the citizens and delivered to the clergy of the Great Church a letter written with red letters and secured by a gold seal and silk thread, steeped in the blood of the mussel, conferring on them the annual sum of two hundred pounds in silver coins. It is said that Axuch carried a second royal letter written in red awarding the same amount in gold coins; since the not unreasonable notion had occurred to the emperor that Isaakios, on learning of his father's death and his young brother's acclamation as sovereign, might incite rebellion in the City on the grounds that he had a better right by birth to the crown, or that the

In such wise they prepared for the imperial arrival. The emperor completed the obsequies of his father and placed the body aboard ship among the fleet anchored in the Pyramos River which fattens Mopsuestia and flows into the sea. Putting in order the affairs of Antioch in the brief time allowed him and setting out from Cilicia, he marched through upper Phrygia. It was at this time [c. 8 May 11431 that Andronikos Komnenos, Manuel's cousin on his father's side (he later reigned as tyrant over the Romans), and Theodore Dasiotes, who was married to Maria, the daughter of Manuel's brother, the sebastokrator Andronikos, were cap- tured by the Turks and taken to Mas`ud, who was then ruler of Ikonion. While hunting wild game, they turned off the road taken by the army and unawares fell into the hands of the enemy; stalking game, they themselves fell prey to the hunters of men. The emperor, who was unable at the time to fix his mind on any other course of action but was wholly absorbed by the enterprise at hand, deemed it inexpedient to delay even a little, nor did he take thought of these men, which would have been the proper thing to do, and come to their aid as befitted the royal dignity. He freed them afterwards without paying ransom, and he recovered for the Romans the town of Prakana, situated near Seleukeia and besieged by the Turks.

When Manuel arrived in the queen of cities [c. July 1143], he was warmly welcomed by her inhabitants both as heir to the paternal throne and because, even though he was a mere lad, he had the deep understanding of those grown old in affairs of state; he had shown himself to be skilled in war, venturesome and undaunted in the face of danger, high minded and eager to give battle. The youth had a handsome face which as graced by a gentle smile; he was tall but slightly stooped. In complexion he was neither snow-white like those reared in the shade nor the color of deep black smoke like those exposed to the burning rays of the sun; he was, consequently, not fair-complexioned but swarthy in appearance.

The citizenry crowded round with arms outstretched, shouting out acclamations, when Manuel jubilantly entered the palace. As he reached the palace, and was about to enter through the gate past which only the emperors were allowed to dismount, the horse carrying the emperor, an Arabian stallion with a high, arched neck, neighing loudly and frequently striking the pavement with his hooves, and advancing without restraint and proudly wheeling about, finally crossed over the threshold. To those who were skilled in such techniques, this episode appeared to be propitious, and of these, those who gaze at the sky while barely seeing what is at their feet foretold, on the basis of the equine configur quent whirlings around, a long life for the emperor. Offering thanks to God on the occasion of his entrance and acclamation as emperor, Manuel turned his attention to who should succeed to the patriarchal throne and take the helm of the Church and place the imperial crown on his head in the Lord's temple, for Leon Stypes had departed the world of men in death. Manuel communicated his views to his kin, the members of the senate, and the clergy; although many were nominated to the supreme high priesthood, the deciding and nearly unanimous vote went to the monk Michael from the Monastery of Oxeia, who was both renowned for his virtue and erudite in our learning.

<As soon as Michael was, promoted as patriarch, he forthwith anointed his anointer upon his entrance into the sacred palace [probably August 1143]. The brother Isaakios was reconciled with the emperor, and, to the surprise of many, they pledged fraternal goodwill to one another. Isaakios was irascible and for the slightest cause would inexplicably be impelled to inflict inordinate punishments on many. He nurtured, furthermore, an ignoble timidity, so much so that he was unmanly. His father John, the best of emperors, was deemed happy by all and of glorious and blessed memory for the added reason that he had rightly chosen Manuel to reign as emperor above Isaakios.

The assembly, lamenting at his words, gladly received Manuel as emperor as though he were appointed by lot or election. Afterwards, the father, after addressing his son and giving him sound advice, crowned him with the imperial fillet and put on him the purple-bordered paludamentum. Then the troops were assembled, and they proclaimed Manuel emperor of the Romans, and each of the nobles, with his retinue standing apart, loudly acclaimed the new sovereign. Thereupon, when the Holy Scriptures had been brought forth, everyone he assembly, lamenting at his words, gladly received Manuel as emperor as though he were appointed by lot or election. Afterwards, the father, after addressing his son and giving him sound advice, crowned him with the imperial fillet and put on him the purple-bordered paludamentum. Then the troops were assembled, and they proclaimed Manuel emperor of the Romans, and each of the nobles, with his retinue standing apart, loudly acclaimed the new sovereign. Thereupon, when the Holy Scriptures had been brought forth, everyone confirmed on them his goodwill and loyalty to Manuel. The initiator and celebrant of these ceremonies was the grand domestic, whose intention was to dissolve and dissipate the attempts at disturbance and rebellion by the ambitious and to blunt the assistance given by a good many to several of the emperor's kin, who, putting forth seniority of birth as a great and venerable tradition and magnifying their connection to the imperial family through marriage, deemed themselves more worthy to rule the empire.

The assembly, lamenting at his words, gladly received Manuel as emperor as though he were appointed by lot or election. Afterwards, the father, after addressing his son and giving him sound advice, crowned him with the imperial fillet and put on him the purple-bordered paludamentum. Then the troops were assembled, and they proclaimed Manuel emperor of the Romans, and each of the nobles, with his retinue standing apart, loudly acclaimed the new sovereign. Thereupon, when the Holy Scriptures had been brought forth, everyone he assembly, lamenting at his words, gladly received Manuel as emperor as though he were appointed by lot or election. Afterwards, the father, after addressing his son and giving him sound advice, crowned him with the imperial fillet and put on him the purple-bordered paludamentum. Then the troops were assembled, and they proclaimed Manuel emperor of the Romans, and each of the nobles, with his retinue standing apart, loudly acclaimed the new sovereign. Thereupon, when the Holy Scriptures had been brought forth, everyone confirmed on them his goodwill and loyalty to Manuel. The initiator and celebrant of these ceremonies was the grand domestic, whose intention was to dissolve and dissipate the attempts at disturbance and rebellion by the ambitious and to blunt the assistance given by a good many to several of the emperor's kin, who, putting forth seniority of birth as a great and venerable tradition and magnifying their connection to the imperial family through marriage, deemed themselves more worthy to rule the empire.

Several days after these events, Emperor John departed this life, having reigned twenty-four years and eight months [15 August 1118 - 8 April 1143]. He had governed the empire most excellently, and his life was well pleasing to God; in moral character he was neither dissolute nor incontinent; by way of gifts and expenditures he pursued magnificence, as is evidenced by his frequent distributions of gold coins to the City's inhabitants and by the many beautiful and large churches he built from their foundations. More than all others, he was a lover of glory, and, he was so fastidious as to the decorum and deportment of the members of his family that he would inspect the cut of their hair and carefully scrutinize the shoes on their feet to see if the leather had been sewn to the exact shape of the foot. He swept the palace clean of idle and filthy conversation during public audiences, of profligacy in food and dress, and of all else that was ruinous and destructive of life; playing the role of grave chastiser and desiring that his attendants should emulate him, he never stopped in the pursuit of every virtue. I do not mean that by behaving in this fashion he was lacking in the graces, inscrutable, inaccessible, sullen in appearance, knitted-browed, or even wrathful. He presented himself to public view as a model of every noble action, and when enjoying a respite from public matters, he would avoid the commotion of large crowds, turning a deaf ear to their babbling and jabbering; his speech was dignified and elegant, but he did not spurn repartee or in any way hold back and stifle laughter. He only just failed to reach the very summit of self-control and steadfastness and barely escaped the charge of parsimony; depriving no one of life nor inflicting bodily injury of any kind throughout his entire reign, he has been deemed praiseworthy by all, even to our own he crowning glory, so to speak, of the Komnenian dynasty to sit on the Roman throne, and one might well say that he equaled some of the best emperors of the past and surpassed the others.

Several days after these events, Emperor John departed this life, having reigned twenty-four years and eight months [15 August 1118 - 8 April 1143]. He had governed the empire most excellently, and his life was well pleasing to God; in moral character he was neither dissolute nor incontinent; by way of gifts and expenditures he pursued magnificence, as is evidenced by his frequent distributions of gold coins to the City's inhabitants and by the many beautiful and large churches he built from their foundations. More than all others, he was a lover of glory, and, he was so fastidious as to the decorum and deportment of the members of his family that he would inspect the cut of their hair and carefully scrutinize the shoes on their feet to see if the leather had been sewn to the exact shape of the foot. He swept the palace clean of idle and filthy conversation during public audiences, of profligacy in food and dress, and of all else that was ruinous and destructive of life; playing the role of grave chastiser and desiring that his attendants should emulate him, he never stopped in the pursuit of every virtue. I do not mean that by behaving in this fashion he was lacking in the graces, inscrutable, inaccessible, sullen in appearance, knitted-browed, or even wrathful. He presented himself to public view as a model of every noble action, and when enjoying a respite from public matters, he would avoid the commotion of large crowds, turning a deaf ear to their babbling and jabbering; his speech was dignified and elegant, but he did not spurn repartee or in any way hold back and stifle laughter. He only just failed to reach the very summit of self-control and steadfastness and barely escaped the charge of parsimony; depriving no one of life nor inflicting bodily injury of any kind throughout his entire reign, he has been deemed praiseworthy by all, even to our own he crowning glory, so to speak, of the Komnenian dynasty to sit on the Roman throne, and one might well say that he equaled some of the best emperors of the past and surpassed the others.

click here for icons of christ

click here for icons of christ click here for icons of the theotokos

click here for icons of the theotokos click here for icons of angels

click here for icons of angels click here for icons of saints

click here for icons of saints