In spring 527 Justin fell ill, and Justinian was proclaimed augustus in April; four months later Justin died, and Justinian succeeded him. His reign lasted until 565, thirty-eight years in all – or forty-seven, if one includes his stint as the power behind Justin’s throne. This was an exceptionally long reign and its duration would have been an achievement in itself. But there was much else besides: reform of the legal code; reconquest of Roman territories in North Africa, Italy and Spain; grandiose rebuilding projects, notably the rebuilding of the centre of Constantinople, including the Great Church of the Holy Wisdom, St Sophia; the closure of the Platonic Academy in Athens; and a religious policy culminating in the fifth ecumenical council, held at Constantinople in 553 (or, to adopt a different perspective, in his lapse into heresy in his final months). The temptation to see all these as parts of a jigsaw which, when correctly fitted together, yield some grand design is hard to resist. And then there is glamour, in the person of Theodora, the woman he married. In doing this, Justinian circumvented the law forbidding marriage between senators and actresses; even Procopius acknowledges her beauty, while regarding her as a devil incarnate. He wrote a malicious account of Theodora’s meddling in the affairs of state in his Secret history. Procopius also relates how during the so-called Nika riot in 532, when Justinian was terrified by the rioting against his rule and was contemplating flight, Theodora persuaded him to stay and face either death or victory with the dramatic words, ‘the empire is a fair winding-sheet.’ All this prepares the way for assessments of Theodora that rank her with Byzantine empresses like Irene or Zoe, both of whom (unlike Theodora) assumed imperial power in their own right, albeit briefly.

The ‘grand design’ view of Justinian’s reign sees all his actions as the deliberate restoration of the ancient Roman empire, though a Roman empire raised to new heights of glory as a Christian empire confessing the orthodox faith. According to this view, reconquest restored something like the traditional geographical area of the empire; law reform encapsulated the vision of a Christian Roman empire, governed by God’s vicegerent, the emperor; the capital’s splendid buildings, not least the churches, celebrated the Christian court of New Rome, with the defensive buildings described by Procopius in the later books of his Buildings serving to preserve in perpetuity the newly reconquered Roman world. The defining of Christian orthodoxy, together with the suppression of heterodoxy, whether Christian heresy or pagan philosophy, completes the picture...

Justinian’s rebuilding programmes likewise fit uneasily into the idea of a grand design. Our principal source for Justinian’s extensive building activity is Procopius’ Buildings, which takes the form of a panegyric and consequently presents the fullest and most splendid account, drawing no distinction between new building work, restoration or even routine maintenance. As we saw earlier, the building of fortresses along the frontier, along the Danube and in Mesopotamia, to which Procopius devotes so much space, should not all be attributed to Justinian himself: as archaeological surveys have shown (and indeed other contemporary historians assert, even Procopius himself in his Wars), much of this was begun by Anastasius. And the great wonders with which Procopius begins his account, when describing the reconstruction of the centre of Constantinople, were consequent upon the devastation wrought by the Nika riot of 532, which Justinian can hardly have planned. But however fortuitous the occasion, the buildings erected in the wake of the riot are works of enduring magnificence, none more so than the church of the Holy Wisdom, St Sophia. Contemporary accounts are breathtaking. Procopius says:

The church has become a spectacle of marvellous beauty, overwhelming to those who see it, but to those who know it by hearsay altogether incredible. For it soars to a height to match the sky, and as if surging up from amongst the other buildings it stands on high and looks down on the remainder of the city, adorning it, because it is a part of it, but glorying in its own beauty, because, though a part of the city and dominating it, it at the same time towers above it to such a height that the whole city is viewed from there as from a watch-tower.

He speaks too ‘of the huge spherical dome which makes the structure excep- tionally beautiful. Yet it seems not to rest on solid masonry, but to cover the space with its golden dome suspended from heaven.’ Contemporaries were struck by the quality of light in the Great Church: ‘it abounds exceedingly in sunlight and in the reflection of the sun’s rays from the marble. Indeed one might say that its interior is not illuminated from without by the sun, but that the radiance comes into being within it, such an abundance of light bathes the shrine.’ Paul the Silentiary, speaking of the church restored after the collapse of the dome in 558, says ‘even so in the evening men are delighted at the various shafts of light of the radiant, light-bringing house of resplendent choirs. And the calm clear sky of joy lies open to all driving away the dark-veiled mist of the soul. A holy light illuminates all.’ This stress on light as an analogy of divinity chimes in well with the vision found in the writings ascribed to Dionysius the Areopagite (commonly known as Pseudo-Dionysius); a fact surely with bearing on the huge popularity these writings were soon to assume.

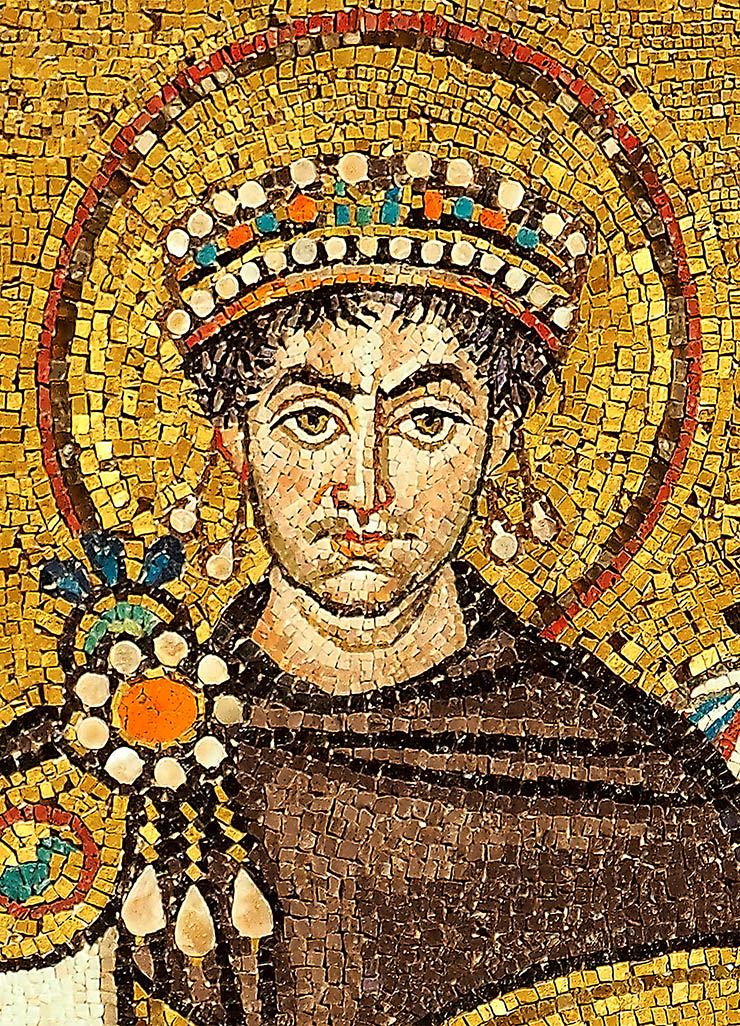

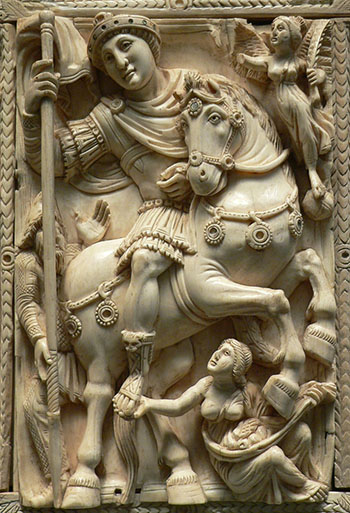

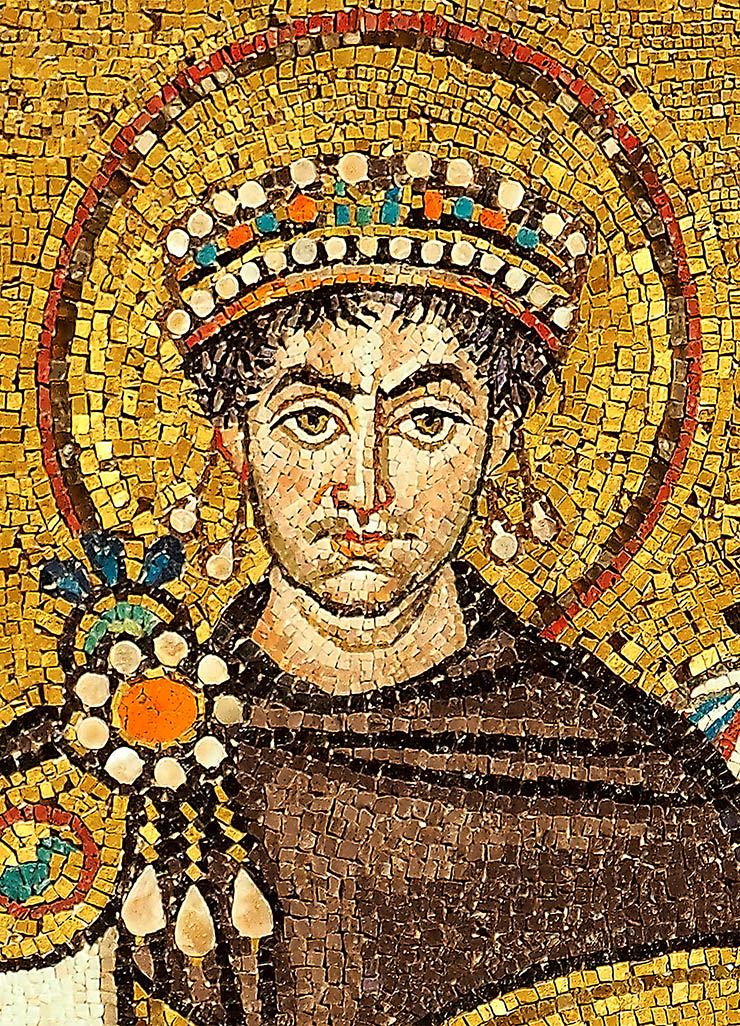

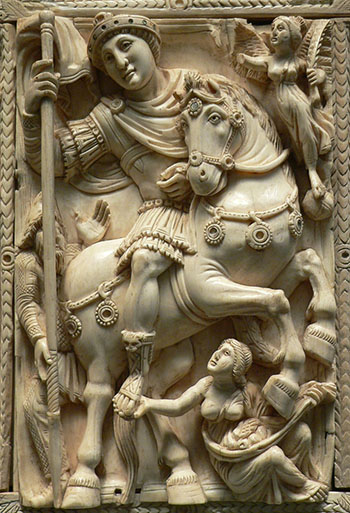

The novel design of the church, with its dome forming an image of the cosmos, was immensely influential: there are many smaller Byzantine imitations of St Sophia, and the suggestion of the church as a mim ̄esis of the cosmos influenced later interpretations of the liturgical action taking place within (see the Mystagogia of the seventh-century Maximus the Con- fessor and the commentary on the liturgy ascribed to the eighth-century patriarch of Constantinople, Germanos). But it may not have been novel: recent excavations in Istanbul have revealed the church of St Polyeuktos, built by the noblewoman Anicia Juliana in the late 520s, which seems in many respects to have foreshadowed Justinian’s Great Church.18 Original or not, St Sophia and Justinian’s other buildings in the capital created a public space in which to celebrate a world-view in which the emperor ruled the inhabited world (the oikoumene ̄), with the support of the court, the prayers of the church and to the acclamation of the people. These buildings included more churches, the restored palace (in front of which, in a kind of piazza, was erected a massive pillar surmounted by a bronze statue of an equestrian Justinian), an orphanage, a home for repentant prostitutes, baths and, finally, a great cistern to secure an adequate water supply in summer. According to Procopius’ description of the mosaic in the great Bronze Gate forming the entrance to the palace, there, amid depictions of Justinian’s victories achieved by his general Belisarius, stood Justinian and Theodora, receiving from the senate ‘honours equal to those of God’.

...

It was in this context that the Nika riot of 532 occurred. Tension between the circus factions, the Blues and the Greens, erupted spectacularly: Jus- tinian was nearly toppled, and much of the palace area, including the churches of St Sophia and St Irene, was destroyed by fire. Popular anger against hate-figures was appeased by the dismissal of the City prefect Eudaemon, the quaestor Tribonian, and the praetorian prefect John of Cappadocia. The riot continued for several days and was only eventually quelled by the massacre of 30,000 people, trapped in the Hippodrome, acclaiming as emperor the unfortunate Hypatius, a general and one of Emperor Anastasius’ nephews. Afterwards Hypatius was executed as a usurper.

The reaction of some Christians to the whole sequence of disasters is captured in the kontakion ‘On earthquakes and fires’, composed by Romanus the Melodist. Romanus wrote and performed this kontakion one Lent while the Great Church of St Sophia was being rebuilt (i.e. between February 532 and 27 December 537). It is a call to repentance after three disasters that represent three ‘blows’ by God against sinful humanity: earthquakes (several are recorded in Constantinople and elsewhere between 526 and 530), drought (recorded in Constantinople in September 530), and finally the Nika riot itself in January 532. These repeated blows were necessary because of the people’s heedlessness. Repentance and pleas for mercy begin, Romanus makes clear, with the emperor and his consort, Theodora:

Those who feared God stretched out their hands to Him, Beseeching Him for mercy and the end of disasters,

And along with them, as was fitting, the ruler prayed too, Looking up to the Creator, and with him his wife,

‘Grant to me, Saviour,’ he cried, ‘as to your David To conquer Goliath, for I hope in you.

Save your faithful people in your mercy,

And grant to them Eternal life.’

When God heard the sound of those who cried out and also of the rulers, He granted his tender pity to the city . . .

The rebuilt city, and especially the Great Church, is a sign of both the care of the emperor and the mercy of God:

In a short time they [the rulers] raised up the whole city

So that all the hardships of those who had suffered were forgotten. The very structure of the church

Was erected with such excellence

As to imitate heaven, the divine throne,

Which indeed offers

Eternal life.

This confirms the picture of recurrent adversity, found in the chroniclers and, it is argued, supported by astronomical and archaeological evidence. But it also indicates the way in which religion attempted to meet the needs of those who suffered – a way that evoked and reinforced the Byzantine world-view of a cosmos ruled by God, and the oikoumene ruled, on God’s behalf, by the emperor. But a study of Romanus’ kontakia also reveals the convergence of the public and imperial apparatus of religion, and private recourse to the Incarnate Christ, the Mother of God and the saints; it also reveals the importance of relics of the True Cross and of the saints as touchstones of divine grace. It is in the sixth century, too, that we begin to find increasing evidence of the popularity at both public and private levels of devotion to the Mother of God, and of religious art – icons – as mediating between the divine realm, consisting of God and his court of angels and saints, and the human realm, desperately in need of the grace which flows from that divine realm; icons become both objects of prayer and veneration, and a physical source of healing and reassurance.

But if the 530s saw widespread alarm caused by natural and human disasters, the 540s saw the beginning of an epidemic of bubonic plague that was to last rather more than two centuries. According to Procopius it originated in Egypt, but it seems very likely that it travelled from the east along trade routes, perhaps the silk roads. Plague appeared in Constantinople in spring 542 and had reached Antioch and Syria later in the same year. Huge numbers died: in Constantinople, it has been calculated, around 250,000 people died, perhaps a little over half the population. Few who caught the disease survived (one such being, apparently, Justinian himself ); those who died did so quickly, within two or three days. Thereafter the plague seems to have declined somewhat in virulence, but according to the church historian Evagrius Scholasticus, there was severe loss of life in the years 553–4, 568–9 and 583–4. Historians disagree about the probable effect of the plague on the economic life of the eastern empire: some take its impact seriously; others, following a similar revision in the estimate of the effects of the Black Death in the fourteenth century, think that the effect of the plague has been exaggerated.

In the final months of his life, Justinian himself succumbed to heresy, the so-called Julianist heresy of aphthartodocetism, an extreme form of monophysitism named after Julian, bishop of Halicarnassus who died c. 527, and which Justinian promulgated by an edict. This is recounted both by Theophanes and by Eustratius, in his Life of Eutychius, patriarch of Constantinople, who was deposed for refusing to accept Justinian’s newly found religious inclination, and has been generally accepted by historians. However, it has been questioned by theologians, who cite evidence for Justinian’s continued adherence to a Christology of two natures, together with evidence that he was still seeking reconciliation between divided Christians: not only with the Julianists themselves, which might indeed have led to orthodox suspicion of Julianism on Justinian’s part, but also with the so-called Nestorians of Persia. The question is complex, but seems to be open...

Justinian died childless on 14 November 565. The succession had been left open. One of his three nephews, called Justin, secured election by the senate and succeeded his uncle; he had long occupied the minor post of cura palatii but he was, perhaps more significantly, married to Sophia, one of Theodora’s nieces. The only serious contender was a second cousin of Justinian’s, also called Justin: one of the magistri militum, he was despatched to Alexandria and murdered, reportedly at the instigation of Sophia.

Download the complete Cambridge History of the Byzantine Empire by clicking here.

click here for icons of christ

click here for icons of christ click here for icons of the theotokos

click here for icons of the theotokos click here for icons of angels

click here for icons of angels click here for icons of saints

click here for icons of saints