By Niketas Chonates from O City of Byzantium

IN this manner, then, Isaakios Angelos lost his throne and was divested of power with ease. He was deprived of his sight by those whom he had imagined led him by the hand as though they were his own eyes, for what could be closer and more trustworthy than a brother, and he beloved? If water drowns us, then what shall we men drink? And if our limbs are armed against one another, how can they possibly work together so that we may live? But the healing art mixes from contrary bodies a salutary antidote; and some men have risen up against one another, disregarding the noble gifts of nature because of evil-mindedness and the love for greater glory. It is for this reason that the barbarian nations regard the Romans with contempt. This they reckoned to be the consequence of all the deplorable events which had gone before by which administrations were constantly overthrown and one emperor replaced by another. There were those who withdrew from close friendships and forswore their old associations; they would say, "If the brother is not safe, then what man is? And whenever certain individuals revealed their secret intentions to others, the latter, citing the example of recent events, suspected that their intimacy was contrived.

Alexios, now on the throne, never realized that he had overthrown himself by deposing his brother. As soon as he had leaped onto the imperial seat by means of this headlong transgression, he searched after his brother's vestments and crown; donning these, he was proclaimed emperor and autokrator by all the military companies and members of the senate and immediately informed his wife and the officials of the City of what had come to pass.

Those who had helped him come to power he rewarded for their zealous support, and he flattered the entire population for going over to him so readily and avoiding political strife. Without rhyme or reason he began to hand out the monies amassed by Isaakios for military operations to satisfy the requests of one and all. When these were depleted because of his prodigal and disparate distribution, he granted small productive farmlands and public revenues to the petitioners. Once these were exhausted, he increased the illustrious dignities. He did not raise up someone held in high repute because of his learning or did he elevate a dignitary to the next successive grade, but he raised up and promoted everyone, both him who had received some dignity but briefly and him who had never been considered worthy even of the lowest rank, to the highest and supreme dignity. Thus the highest honor became dishonor- able and the love of honor a thankless pursuit. Many equated promotion with demotion when later they were justly and deservedly promoted to those dignities which others had received undeservedly, awarded the same honor and esteem as those who deserved the dignity but who were overlooked and reckoned as ignoble.

Those who had helped him come to power he rewarded for their zealous support, and he flattered the entire population for going over to him so readily and avoiding political strife. Without rhyme or reason he began to hand out the monies amassed by Isaakios for military operations to satisfy the requests of one and all. When these were depleted because of his prodigal and disparate distribution, he granted small productive farmlands and public revenues to the petitioners. Once these were exhausted, he increased the illustrious dignities. He did not raise up someone held in high repute because of his learning or did he elevate a dignitary to the next successive grade, but he raised up and promoted everyone, both him who had received some dignity but briefly and him who had never been considered worthy even of the lowest rank, to the highest and supreme dignity. Thus the highest honor became dishonor- able and the love of honor a thankless pursuit. Many equated promotion with demotion when later they were justly and deservedly promoted to those dignities which others had received undeservedly, awarded the same honor and esteem as those who deserved the dignity but who were overlooked and reckoned as ignoble.

Title to property was easily acquired; no matter what document was presented to the emperor, he signed it immediately, even though it contained solecisms and the petitioner proposed to sail on land and plow the sea, or to move the mountains into the depths of the sea, or, as the myth would have it, to pile Athos on Olympos.

Having thus accomplished all these things, or perhaps it would be more fitting to say, having contributed to their accomplishment, and compelled to comply to the time and the state of affairs, Alexios allowed the troops to disband and return to their homes, without regard for the attacks of the Vlachs and Cumans who carried off everything before them. He did not hasten to reach the City. As his brother had already been seized and blinded and there was nothing to fear, he proceeded at a slow pace, tarrying at the stages along the way.

The officials of the state had already declared for him, his entry had been made ready by his wife Euphrosyne, and at least a faction of the senate had happily accepted the outcome of events. When the citizens heard the proclamations, they engaged in no seditious act but remained calm from the beginning and applauded the news, neither remonstrating nor being inflamed by righteous indignation at being deprived by the troops of their customary right to elect the emperor.

As soon as Alexios's wife Euphrosyne had set out for the Great Palace, some troublemakers formed a cabal from among the artisans and the rabble. They rallied around a certain Alexios Kontostephanos, a stargazer who had long been lying in wait for the throne, and proclaimed him emperor in the agora, crying out that they had had their fill of the Komnenoi and no longer wished to be ruled by them. When Empress Euphrosyne had entered the Great Palace at great risk, those members of distinguished families who had escorted her recklessly attacked Kontoste- phanos rather than with prudence. The vulgar city mob was dispersed, and Kontostephanos was apprehended and thrown into prison.

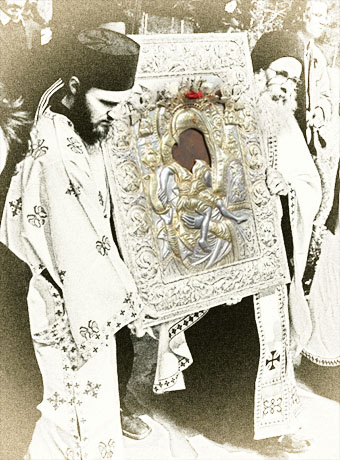

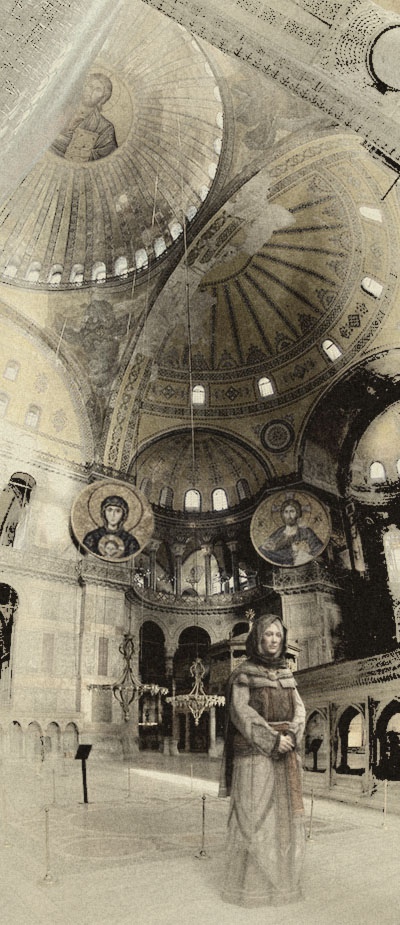

Once calm was restored among the City's populace, all those inside the church [Hagia Sophia] consented to the new tyranny, and one of the sacristans, bought off by a few coins (the agitators from the marketplace and several judges-whose names I cannot bring myself to mention- followed suit), ascended the holy pulpit and began to chant Alexios's acclamation without waiting for the chief shepherd's signal. But the latter, who resisted for a short time since the self-called [Alexios] had not made his appearance, changed his mind about the previous emperor [Isaakios]. When the patriarch weakened, there was no one left to offer resistance. All came together to the palace and deserted to the empress as though they were slaves; even before they saw the tyrant or knew exactly what had happened to the previous monarch, they prostrated themselves before the alleged emperor's wife and placed their heads under her feet as footstools, nuzzled their noses against her felt slipper like fawning puppies, and stood timidly at her side, bringing their feet together and joining their hands. Thus these stupid men were ruled by hearsay, while the wily empress, adapting easily to circumstances, gave fitting answers to all queries and put the foolish Byzantines in a good humor, beguiling them with her fair words. Lying on their backs, in the manner of hogs, with their bellies stroked and their ears tickled by her affable greetings, they expressed no righteous anger whatsoever at what had taken place. In this manner was the way paved for Emperor Alexios's entry without bloodshed and with absolutely no one being deprived of his properties.

Once calm was restored among the City's populace, all those inside the church [Hagia Sophia] consented to the new tyranny, and one of the sacristans, bought off by a few coins (the agitators from the marketplace and several judges-whose names I cannot bring myself to mention- followed suit), ascended the holy pulpit and began to chant Alexios's acclamation without waiting for the chief shepherd's signal. But the latter, who resisted for a short time since the self-called [Alexios] had not made his appearance, changed his mind about the previous emperor [Isaakios]. When the patriarch weakened, there was no one left to offer resistance. All came together to the palace and deserted to the empress as though they were slaves; even before they saw the tyrant or knew exactly what had happened to the previous monarch, they prostrated themselves before the alleged emperor's wife and placed their heads under her feet as footstools, nuzzled their noses against her felt slipper like fawning puppies, and stood timidly at her side, bringing their feet together and joining their hands. Thus these stupid men were ruled by hearsay, while the wily empress, adapting easily to circumstances, gave fitting answers to all queries and put the foolish Byzantines in a good humor, beguiling them with her fair words. Lying on their backs, in the manner of hogs, with their bellies stroked and their ears tickled by her affable greetings, they expressed no righteous anger whatsoever at what had taken place. In this manner was the way paved for Emperor Alexios's entry without bloodshed and with absolutely no one being deprived of his properties.

After several days, Alexios himself entered Byzantion. As he sat freshly bathed on a gold-spangled couch at the outer Philopation, as it was called, he gladly admitted to his presence all those who approached him and showed no remorse for what he had done to his brother. Certain judges of the velum, who did not find the time opportune for flattery, indulged in ribaldry which drew derision down upon them. There were those who groaned at what they saw; they were astonished to see the imperial ornaments which Isaakios had had sewn for himself now worn by his brother. From this change in rule they augured the beginning of fresh calamities, recalling the deeds of Osiris and Typhon that afflicted Egypt.

After several days, Alexios himself entered Byzantion. As he sat freshly bathed on a gold-spangled couch at the outer Philopation, as it was called, he gladly admitted to his presence all those who approached him and showed no remorse for what he had done to his brother. Certain judges of the velum, who did not find the time opportune for flattery, indulged in ribaldry which drew derision down upon them. There were those who groaned at what they saw; they were astonished to see the imperial ornaments which Isaakios had had sewn for himself now worn by his brother. From this change in rule they augured the beginning of fresh calamities, recalling the deeds of Osiris and Typhon that afflicted Egypt.

When Alexios entered the celebrated Great Church of the Wisdom of God so that according to custom he might be anointed and invested with the insignia of sovereignty, the first thing he did was to sign the symbol of the faith in imperial ink. Afterwards he approached the so-called Beautiful Portals of the temple and remained there for some time, awaiting to receive the signal for the exact moment of his entrance [into the narthex] from the timekeepers in the Catechoumeneia above. When he had left the temple and was about to mount his horse (an Arabian stallion kept at rack and manger), which was led forward by the reins by the protostrator [Manuel Kamytzes], an unusual and wondrous event took place. The horse, its eyes blood red and ears erect, snorted, kicked up its front hooves, repeatedly struck the ground, and bounded about spiritedly; driven wild with rage against him, it shunned Alexios as though it disdained to carry him on its back. Alexios made repeated attempts to mount the horse, but, kicking up its front hooves and wheeling about, it repulsed him. After much coaxing and stroking of its neck, it finally seemed to calm down, to cease making its proud gyrations and thrashing its legs in the air. The emperor leaped on it and grabbed the reins, but the horse, as though tricked into accepting the rider against its will, misbehaved as before, lifting up its legs and neighing loudly. Nor did it end its Bacchic frenzy until it had knocked the bejeweled crown from the emperor's head to the ground so that certain parts of it were shattered and had thrown him off like a ball as well. When another horse was brought forward and Alexios paraded with a broken crown, this was deemed an inauspicious portent of the future: that he would be unable to preserve the empire intact but would fall from his lofty throne and be ill-treated by his enemies.

Accompanying the emperor in the procession on horseback were his two sons-in-law, Andronikos Kontostephanos and Isaakios Komnenos, and his paternal uncle, the aged John Doukas, who, during this triumphal procession, had the following unexpected event befall him. Without any visible cause, without anyone agitating the mule he was riding, the sebas- tokrator's crown tumbled from the top of his head to the ground. When the spectators saw this, they shouted and then laughed when they observed his bald head which earlier had been concealed by the crown but now shined like a full moon. But Doukas turned necessity into an occasion for good cheer and high spirits (for one can hardly take umbrage at the fortuitous circumstance) and regarded the merriment of the many over this happenstance a pleasurable amusement. He rejoiced with them without the slightest show of indignation.

The emperor repudiated his patronymic of Angelos and chose that of Komnenos instead, either because he held the former in low esteem in comparison with the celebrated name of Komnenos, or because he wished to have his brother's surname disappear with him. Everyone supposed that once Alexios was proclaimed emperor and calm had been restored to the empire, he would appear in arms and keep the field and not shun the urgent business at hand. They thought that he would remedy previous failures to take action, and especially all those evils they had suffered at the hands of the barbarians because there was no one to oppose them or to show the slightest concern. He, however, did the exact opposite, and now that he had reached the highest goal which he had worked so hard to attain, he relaxed, deeming that he was given the throne not to exercise lawful dominion over men but to supply himself with lavish luxuries and pleasures.

The emperor repudiated his patronymic of Angelos and chose that of Komnenos instead, either because he held the former in low esteem in comparison with the celebrated name of Komnenos, or because he wished to have his brother's surname disappear with him. Everyone supposed that once Alexios was proclaimed emperor and calm had been restored to the empire, he would appear in arms and keep the field and not shun the urgent business at hand. They thought that he would remedy previous failures to take action, and especially all those evils they had suffered at the hands of the barbarians because there was no one to oppose them or to show the slightest concern. He, however, did the exact opposite, and now that he had reached the highest goal which he had worked so hard to attain, he relaxed, deeming that he was given the throne not to exercise lawful dominion over men but to supply himself with lavish luxuries and pleasures.

Like a steersman who is compelled by the waves to let go of the rudder, he withdrew from the administration of public affairs and spent his time wearing golden ornaments and giving ear to, and granting, every petition of those who had helped raise him to power. With both hands he unsparingly poured out the monies that Isaakios had amassed, and they were scattered like heaps of chaff and blown away like summer dust to fill the slow bellies. To the difficulty of collecting revenues hereafter and to the loss that served no purpose, he gave no thought. Only later, when he had need of funds, did this emperor who was devoted to futile munificence censure himself for his prodigality.

This emperor's wife was very manly in spirit and boasted of a natural sophist tongue, eloquent and honeyed. Most adept at prognosticating the future, she knew how to manage the present according to her own will and pleasure, and in everything else she was a monstrous evil. I do not speak of the embellishments, and the squandering of the empire's sub- stance in luxury, and the fact that, thanks to her happy nature, she was able to prevail over her husband to alter established conventions and devise new ones (these things, however, have no place in the history, and if they are improper for women, this is also true of empresses). By dis- honoring the veil of modesty, she was hooted and whistled at and became a reproach to her husband. At first, everyone believed that he knew of her improprieties and was simply pretending to be ignorant of them, but from his actions later, when his wife's activities were disclosed, he clearly demonstrated that he was not ignorant of her effronteries. These things shall be revealed at the proper time by this history.

Because the empress had overstepped the bounds and held in contempt the conventions of former Roman empresses, the empire was divided into two dominions. It was not the emperor alone who issued commands as he chose; she gave orders with equal authority and often nullified the emperor's decrees, altering them to her liking. And whenever the emperor was about to receive in audience an important foreign embassy, two sumptuous thrones were set side by side. Sitting in council with the emperor, she presided dressed in splendid attire, her crown embellished with gems and translucent pearls and her neck adorned with costly small necklaces. At times they stood apart in other imperial buildings and appeared in turn, thus dividing their subjects between them. If, at first, they made obeisance to the emperor, they would then move on to the empress and make an even greater prostration before her. Not a few of the emperor's blood relations, for whom the highest offices had been reserved, would draw nigh, and placing their shoulders like wooden beams under the splendid and lofty throne, elevated the empress.

Because the empress had overstepped the bounds and held in contempt the conventions of former Roman empresses, the empire was divided into two dominions. It was not the emperor alone who issued commands as he chose; she gave orders with equal authority and often nullified the emperor's decrees, altering them to her liking. And whenever the emperor was about to receive in audience an important foreign embassy, two sumptuous thrones were set side by side. Sitting in council with the emperor, she presided dressed in splendid attire, her crown embellished with gems and translucent pearls and her neck adorned with costly small necklaces. At times they stood apart in other imperial buildings and appeared in turn, thus dividing their subjects between them. If, at first, they made obeisance to the emperor, they would then move on to the empress and make an even greater prostration before her. Not a few of the emperor's blood relations, for whom the highest offices had been reserved, would draw nigh, and placing their shoulders like wooden beams under the splendid and lofty throne, elevated the empress.

Three months had not yet passed [before 8 July 1195] when the news arrived that a certain Alexios from Cilicia, who had assumed the name of emperor Manuel's son Alexios, had gone over to the satrap of the city of Ankara [Muhi al-Din Mas `Udshah] and had been received as the true son of Emperor Manuel. Although this man knew that he would not accomplish his objective (for he knew that Emperor Alexios had been strangled by Andronikos, he deemed this would embroil the emperor of the Romans in troubles, for he would thus be pitted against insurrectionists. In this way, friendship with the Romans would become a salable commodity, and he would profit unjustly. Now that the false-Alexios was attacking the Roman towns that bordered Ankara, and prevailing against them because the Turks had sent reinforcements, a certain John Ionopolites,1z80 who had recently been honored by the emperor with the rank of parakoimomenos, was dispatched.

Three months had not yet passed [before 8 July 1195] when the news arrived that a certain Alexios from Cilicia, who had assumed the name of emperor Manuel's son Alexios, had gone over to the satrap of the city of Ankara [Muhi al-Din Mas `Udshah] and had been received as the true son of Emperor Manuel. Although this man knew that he would not accomplish his objective (for he knew that Emperor Alexios had been strangled by Andronikos, he deemed this would embroil the emperor of the Romans in troubles, for he would thus be pitted against insurrectionists. In this way, friendship with the Romans would become a salable commodity, and he would profit unjustly. Now that the false-Alexios was attacking the Roman towns that bordered Ankara, and prevailing against them because the Turks had sent reinforcements, a certain John Ionopolites,1z80 who had recently been honored by the emperor with the rank of parakoimomenos, was dispatched.

Since the eunuch achieved nothing in this matter, the emperor decided that it was necessary that he himself should venture out, in part to negoti- ate a truce with the Turk. With this accomplished, he could easily defeat the impostor, and once the latter was dead, he could then deal with the enemy. But the Turk took full advantage of the opportunity and refused to accept peace terms unless the emperor immediately granted him five hundred pounds of silver in minted coin and thereafter three hundred pounds of silver coins to be paid annually and forty vestments of silk thread supplied the emperor by Thebes of the Seven Gates.

At Melangeia, the emperor was proclaimed autokrator by the inhabitants, but he did not find resolute support against the adversary Alexios. While they devoted themselves to Alexios as emperor of the Romans, they would not forsake the friendship of the false-Alexios; looking with favor on both parties, they vacillated in their sentiments without indicating which of the two they preferred. They gave everyone to understand that being uncommitted they would not announce themselves at once for either one; when the issue was decided they would join the victor. Even in their audiences with the emperor, they did not desist from extolling Alexios. They would often say, "You, too, would be delighted in the man if you saw him, 0 Despot and Emperor. His long, yellowish red hair is adorned as though with filings of gold. A man of goodly stature is he and such a horseman that he cannot be shaken, and it is as though he were fixed in the saddle."

At Melangeia, the emperor was proclaimed autokrator by the inhabitants, but he did not find resolute support against the adversary Alexios. While they devoted themselves to Alexios as emperor of the Romans, they would not forsake the friendship of the false-Alexios; looking with favor on both parties, they vacillated in their sentiments without indicating which of the two they preferred. They gave everyone to understand that being uncommitted they would not announce themselves at once for either one; when the issue was decided they would join the victor. Even in their audiences with the emperor, they did not desist from extolling Alexios. They would often say, "You, too, would be delighted in the man if you saw him, 0 Despot and Emperor. His long, yellowish red hair is adorned as though with filings of gold. A man of goodly stature is he and such a horseman that he cannot be shaken, and it is as though he were fixed in the saddle."

When the emperor replied that Emperor Manuel's son was put to death long ago by Andronikos, that he who had now come forward was an impostor unrelated to the Komnenos family, and even if one should con- cede that he were alive and that this aggressor were he, he, the emperor, would still have a better right to the throne as he held the scepter of the Roman empire in his hand, then the listeners interrupted, and using his own words to refute his arguments, they said, "Do you see, 0 Emperor, how you too have doubts about the youth's identity and how uncertain you are about his death? Be not angry then with those who take pity on the youth on whom the empire has devolved through three generations and who unjustly has been separated from both throne and country."

When the emperor saw that he could not prevail and that nothing was being gained by his presence, he went from one fortress to another. Some he won back from Alexios and others he put to the torch for having gone over to the rebel. Then, having spent two months on campaign, he decided to return and appointed Manuel Kantakouzenos to deal with the Cilician Alexios.

When the emperor saw that he could not prevail and that nothing was being gained by his presence, he went from one fortress to another. Some he won back from Alexios and others he put to the torch for having gone over to the rebel. Then, having spent two months on campaign, he decided to return and appointed Manuel Kantakouzenos to deal with the Cilician Alexios.

Despite the fact that Alexios received ever-increasing assistance from the Turk, and levied tribute from all or nearly all of the fortresses around Ankara, he did not openly war with him. Over a long period of time, he would have been an evil beyond remedy for the Romans had not God taken pity on the fortunes of the Roman empire, appearing as a maker of things new. A certain individual who entered the fortress of Tzoungra put Alexios to the sword at night [c. 1197]. Thus did he vanish, rushing by with the speed of light only to be lost from sight, or like some violent wind that blows in from the Cilician promontory of Korykos and after battering a portion of the Roman land, quickly subsides, having dissi- pated its violence.

Close behind this evil [1195] there followed an even greater one, which appeared to have fallen but shot up like lethal hemlock. This was Isaakios Komnenos, whom I mentioned in my earlier books. Having become both master and destroyer of the island of Cyprus, he was taken captive by the king of England, who was sailing to Palestine across the sea, and presented to one of his compatriots as a slave who wants whipping. It was bruited about everywhere that the rogue suffered a most miserable death, but, as proved later, his demise was only a false rumor; freed from his fetters and released from prison, though this should not have taken place, he made his way quickly to Kaykhusraw, the ruler of the city of Ikonion, and welcomed by the latter as his guest, he rekindled his old passion for the throne. Emperor Alexios, encouraged by Empress Euphrosyne, who was closely related to Isaakios, dispatched many letters recalling him. He stubbornly refused and was vexed at the letters' con- tents, for he said that he had learned only how to rule, not how to be ruled; how to lead others, not how to obey others.

He wrote many letters to the leading men of Asia, proposing no forbidden action nor any seditious act against the established authorities but promising rewards to all those who obeyed him should he succeed in becoming emperor. But just as the goal that he pursued earlier had remained unattainable and in vain had he formed plots which God did not design, so now he was also guilty of futilely contriving to achieve the impossible. Neither did the Turk pay him heed as he wished (he wanted the Turk to follow him in campaign against the Romans with all his forces and to execute all his commands), nor did any of those to whom he wrote in secret lend an attentive ear, but like asps they all stopped up their ears to his incantations. Who, having pursued a bloodthirsty beast, does not see it a short time later springing and making a kill? Or who, having made friends with a venomous serpent, even becoming attached to it and nurturing it in his bosom, is not mortally wounded when it bites and disgorges its venom? However, Isaakios Komnenos gave up the ghost shortly thereafter and joined those other tyrants whom the hand of the Lord utterly destroyed, even though He does not usually immediately execute those salutary measures which He frequently innovates. It pleased Him to lay low the accursed wretch, not by natural death, but by poison given him by a certain cupbearer who was emboldened in this deed by huge bribes from his emperor.

One of the many things Alexios attempted as emperor was to make peace with the Vlachs, and for this purpose he dispatched envoys to Peter and Asan [after 8 April 1195]. He did not, however, conclude a peace treaty as these men responded in immoderate terms and made peace proposals which the Romans found impossible and humiliating.

While the emperor was sojourning in the East, they attacked the Bulgarian themes around Serrai. They defeated the Roman troops encamped there and inflicted great injury on many others, and they took captive Alexios Aspietes, commander of the Romans. They occupied many of the fortresses in those parts, and after strengthening and securing these, they returned home with plunder beyond measure.

To avoid another such disaster, the emperor dispatched his son-in-law, the sebastokrator Isaakios, with a considerable force. Some of the Vlachs advised Asan not to carry out any further violent attacks against the Romans and to be mindful of military stratagems (for they had heard that the emperor was skilled in warfare and much more capable than his brother). Asan replied arrogantly that one should not always pay heed to rumors. One should not accept the courage of a particular man as fact and cower before him; neither should one make light of another and dismiss him before one has experience of him because others have described him as a coward and a weakling, nor should one reject a rumor outright as worthless, especially when it is widely bruited about, for the actions of men who are calumniated or applauded are drawn by rumor as by a magnet. Moreover, the eye sits in judgment on what is reported, and thus the rumor will be accepted as true or, besmeared with myrrh, as false and let loose to fly elsewhere.

The ears do not know what is taking place, but when information enters them from the mouths of the people, they guard against the unfavorable reports which frequently assail them. The sure arbitrator of events is the eye, which is an undeceived witness of those things it observes; its certainty does not come from outside itself as does that of the ear, which must rely on hearsay.

You should not be terrified because rumor proclaims the present emperor of the Romans a courageous man; rather, it is necessary to consider whether he is such as he is reputed to be. Let the man's former life be your guide and faultless instructor in this. Were you more discerning, you would see that he has not distinguished himself in anything, or joined battle, or endangered himself on behalf of the Romans by campaigning and toiling alongside his brother as I myself have done by ever laying waste and overrunning the enemy's country, by winning victory after victory, and by piling up trophy upon trophy. Alexios did not obtain the purple robe and the imperial crown as a reward for his labors, but, as he was to demonstrate by his deeds, he laid hold of the scepter as a result of the tricks played by cruel Fortune. That this man, whom I have not observed in combat or harassing the lands of the Mysians by hand and speech and intent, might suddenly turn the tables, I have no way of knowing.

To illustrate, as far as possible, the facts about this man and the rest of his kinsmen, observe, suspended from my lance and blowing in the wind, the ribbons of diverse colors, if not of different webs. These have originated from the same cloth and a single weaver has woven them, yet because of their difference in color they appear to have had a different efficient cause. But this is not the case. The brothers Isaakios and Alexios, the first already deposed from the throne and the second who now dons the tebenna and wears the imperial crown, had the same father, slipped out of the same womb, were born in the same country, and shared everything in common, even though Alexios saw the light of day first. Thus it seems to me there is no difference between the two in warfare, as we shall come to know by experience.

It is necessary, I say, that we prosecute the war vigorously and with the same resolve as heretofore, knowing that as before we shall prevail even in the face of adverse fortune, not to say that the Romans shall suffer an ever worse fate thanks to their loss of morale; defeated by us many times, they were not able, even once, to retrieve their losses. Let me note also that they have drawn down upon their heads the wrath of God by deposing from his rightful dominion Isaakios, who had delivered them from grievous tyranny. Having thus armed themselves against the strong, they will soon be cut down by their enemies as breakers of treaties.

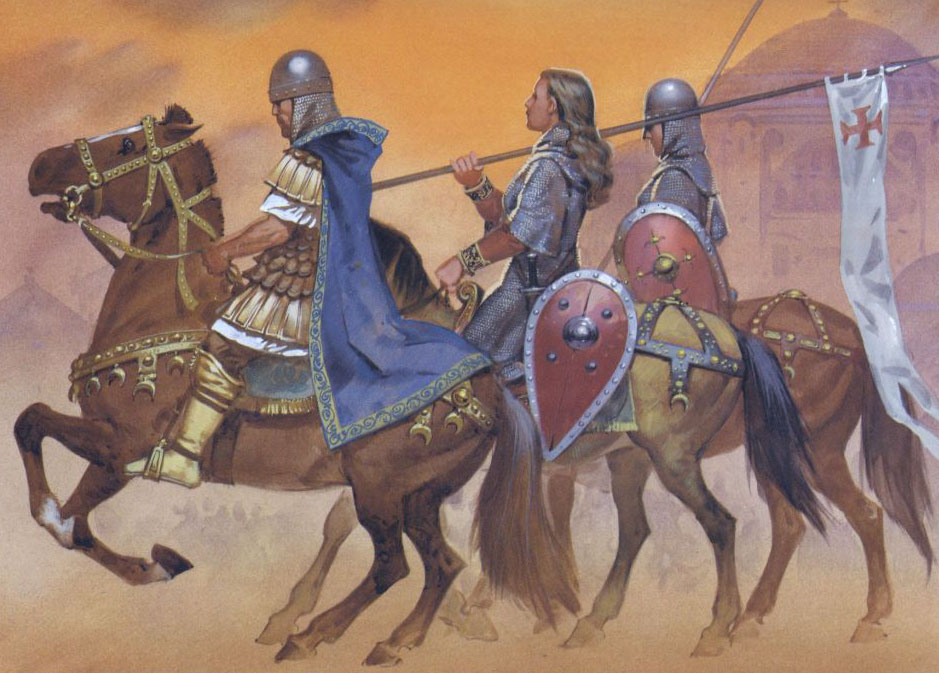

The barbarian, having raised the spirits of his men with such sentiments and bombast, invaded the provinces centered around the Strymon River and Amphipolis. When the sebastokrator Isaakios, who was young and excited over a recent setback of the Vlachs, heard that he had at- tacked Serrai, he rushed out against him on the basis of hearsay without first assessing the enemy's strength. The signal for battle was sounded by the trumpet, rousing the troops to arms, and he was the first to mount his war horse; putting on his armor in great haste, he rode out brandishing his lance at the enemy as though a deer hunt had been arranged for him or hunting games had been prepared somewhere nearby.

After traversing some thirty stades at full speed, the cavalry was worn out and useless when the attack came, and the exhausted, straggling infantry was unfit to take any action afterwards. When he approached the enemy's camp, Asan divided the greater number and the best of his troops into ambuscades. Isaakios, oblivious to this stratagem and trick, proceeded on in Bacchic frenzy, certain that he would defeat the enemy and put them to flight. When the ambushers attacked, therefore, he was trapped as in a hunter's net and lost many of his men; in the end he was taken alive by the Cumans. Like a lion among cattle, the barbarian rushed upon the arriving Roman troops with utter impunity. Not one fought back, but one and all played the coward and streamed into the city of Serrai at full speed, that is, all those who had not been cut down by the sword during the encounter.

The Cuman who captured the sebastokrator concealed him in diverse ways so that he should remain undetected by Asan, for he entertained high hopes that he might get by the Vlachs and bring him to his own haunts, upon which the emperor would pay him a huge ransom. But when it was reported that the commander had been apprehended, a diligent search was conducted and he was brought before Asan. This, then, was the outcome of these events. One of the captive priests, who had been carried off to the Haimos as a prisoner of war and knew the language of the Vlachs, begged Asan to release him and appealed to him to show him mercy. Asan, throwing his head back in denial, refused and said that it had never been his policy to set Romans free but to kill them; for this is also God's will, and he had let him live a long time. The priest, it is said, sighing deeply and with tears in his eyes, rejoined that neither would God be merciful to him, since he had not remembered to show mercy to a needy man who was near to God because he was a priest, that the end of Asan's life was close at hand, and that it would not come as a natural death in soft slumber but in the same manner that he was often accustomed to slaughter by the sword those who were set before him. And the priest's prophecy did not miss its mark; shortly thereafter, when Asan arrived in Mysia, he was slain by one of his own kin [1196].

Asan was put to death in the following manner. A certain man of the same age and habits as he and on whom he looked with great favor (his name was Ivanko) had had clandestine sexual relations with the sister of Asan's wife. Inquiring into the circumstances of the liaison, Asan at first placed the blame on his wife and condemned her to death for covering up the affair. His wife remonstrated with him and managed to lull his murderous gaze and impulse, but later, when he was convinced that it was useless to rant against his wife and had learned all the particulars about this affair, he transferred his wrath from his wife to Ivanko. Outraged, he summoned the man at an untimely hour of the night, but Ivanko, because he realized the untimeliness of the request indicated there was cause and reason, deferred his arrival until the morrow. Asan could not tolerate such nonchalance as a matter of negligence and insisted, and Ivanko, eventually cognizant why he was being summoned, deliberated with his blood relations and friends as to what he should do. They advised him to gird on his long sword and come before Asan, concealing the sword under his outer garment. Should Asan upbraid him gently and moderate his violent and heated insults and whatever else, and as long as no injury was inflicted on his body as chastisement, then he should bravely endure the aggravation of his seizure and ask forgiveness, but should Asan un- sheath his sword, then he should play the man and hasten to forestall his imminent doom and strike mortal blows, sending the shameless and bloodthirsty Asan to the nether world. Ivanko followed their advice. The barbarian, however, had no intention of treating him with moderation.

At first sight of Ivanko, he went berserk and reached for his killer sword, but Ivanko struck him first in the groin and killed him. Ivanko escaped and immediately approached those who were privy to the deed. After he had informed them of the event, he realized, as did they, that the only course open to them was rebellion, since the brothers, kinsmen, and friends of the fallen man would never rest. And should they proceed according to their purpose and will, they would rule Mysia more justly and equitably than had Asan and would not govern everything by the sword as the fallen man had done. Whenever anger required it, they would act accordingly, but should their plans be upset and not proceed according to their desire, they would embark upon another course and turn to those who piloted the Roman ship of state to achieve their end.

As it was still night, they confirmed their decision and urged many others to assist them in their resolutions. Taking possession of Trnovo (this was the best fortified and most excellent of all the cities along the Haimos, encompassed by mighty walls, divided by a river stream, and built on a ridge of the mountain), they resisted the followers of Peter. At the crack of dawn the news of Asan's death was trumpeted from the top of the walls of Trnovo and to those outside and far away. But Peter did not find Ivanko's destruction easy while Ivanko was not able to beat off Peter. Thus Peter was compelled to bide his time, his one hope to over- throw his opponent Ivanko. Ivanko, for his part, recognized that he needed the assistance of the emperor to overcome his adversaries and that he must appeal to him. It was said that it was at the instigation of the sebastokrator Isaakios that Ivanko, who was encouraged in this by many promises, killed Asan, and that Ivanko was especially set on the wing by the pledge of marriage to Isaakios's own daughter Theodora.

But Isaakios gave up the ghost in prison without having effected the murder. Ivanko informed the emperor of the events and exhorted him to send someone with an army to receive Trnovo and to fight along side him to take all of Mysia. Had the Romans quickly performed a salutary deed, and had the emperor shown eagerness in immediately undertaking a sur- prise attack in response to his message, he would have occupied Trnovo and taken all of Mysia without trouble. The emperor, in his stupidity, withdrew once again within the palace like the caterpillar into its cocoon and dispatched the protostrator Manuel Kamytzes, proclaiming him commander-in-chief. Kamytzes set out from Philippopolis with his forces, but on reaching the borders of Mysia on tiptoe, he was unexpectedly compelled to turn back. The troops mutinied, saying, "Where are you taking us? Whom are we to engage in battle? Have we not traversed these mountain passes many times, and not only did we accomplish nothing worthwhile but we also very nearly perished, one and all. Turn back, therefore, turn back, and lead us back to our own land." Confounded by these and other groundless fears, they fled in disarray as though they were being pressed hard by an enemy discharging all kinds of missiles at their backs.

Following this debacle, it was decided that a larger army be dispatched. The situation only worsened, since no one attempted to engage the barbarians in hand-to-hand combat in order to come to the assistance of Ivanko. Despairing and distressed over the affairs at Trnovo, for Peter's followers were ever consolidating their position and his army ever grew in numbers, Ivanko departed and made his way to the emperor. Thus the rule of Mysia was fully transferred once again into the hands of Peter. Even he, however, did not die a natural death. Shortly afterwards [1197], he was run through by the sword of one of his countrymen and died pitiably. The rule of the Vlachs now looked to loannitsa, the third brother.1292 At that time Peter designated his brother loannitsa (who spent a considerable time among the Romans as a hostage as a result of Emperor Isaakios's second campaign against the Mysians but escaped to his own country) to assist him in his labors and share in his rule. Peter, whom none of us met, continued the deceased Asan's policy of plunder- ing Roman lands, nor did Nature bestow upon him any sense of modera- tion towards our empire. So many great battles over so many years were brought to a successful issue by our adversaries that this evil forever troubled the waters of Roman fortunes. Not even a minor victory smiled upon the Romans, and there was not even an illusion of a trophy.

None of the high-throned bishops, who reaped the highest honors, or the thick-bearded monks, who pulled their woolen hoods down to their noses, pondered God's almost total abandonment of us. None preached the need to placate the Deity, nor did any who had the freedom to speak openly before the Roman emperor elaborate on the means of deliverance. It seemed that they all had become good-for-nothing, that they were unable to perceive what was happening and to oppose, the chastisements sent from God. The Hellenes, when informed by the seer Calchas as to the cause of the pestilence, did not ignore the need to cure the evil, even though Agamemnon, the foremost and mightiest of the host, might wax wroth.

Ivanko made his way to the emperor and was warmly received; he proved to be useful to the Romans in many ways. He was tall in stature,very shrewd, in the prime of his physical vigor, and clearly cut a figure of a man of blood, quick to anger and opinionated; his association with the Romans did nothing to temper or moderate his disposition. The emperor, who deemed the man worthy of the marriage proposals made him, put off the wedding rites until the appropriate time (for the bride was still a child mouthing baby talk) and enrolled him among his very powerful kinsmen. He deprived him of none of the privileges of the court and bestowed great wealth upon him. Ivanko, seeing that his betrothed, the emperor's daughter's child, was a minor, gazed fixedly at the rose-colored beauty of her mother Anna, who was as yet a widow, and fancying a superior marriage, he said, "Why do you give me a suckling kid to cover when I am in need of a full grown goat? This man labored primarily in the regions around Philippopolis and served the Romans as a precious bulwark against his own countrymen, who, with the support of the Cumans, would march out ravaging everything in their way [1197-1200]. Sometimes he campaigned with the emperor and proved to be especially effective. Who is able to count the number and cite the times of the onslaughts of the Cumans and the Vlachs throughout the year and the unholy deeds they performed? The devastation of the lands towards the Haimos and the despoiling of the inscribed monuments and pillars of Macedonia and Thrace give a more accurate picture of the damage wrought than any detailed historical account.

Not only did the barbarians to the north, who waged war against us and whom we found hard to face, have the upper hand, but in the East the Roman territories were exposed to destruction by the Turks. The emperor, who refused to make peace with the Turkish ruler of Ankara in Galatia [Muhyi al-Din], partly because there was nothing to be gained from friendship with him, since he was in no position to injure the Romans, and partly because Alexios was niggardly about the money which the Turk demanded in order to keep the peace, spent a year and six months at odds with him [July 1195 to December 1196]. As a result, the Cilician Alexios, strengthened by the dynast of Ankara, accomplished all that we have recounted; the city of Dadibra fell and submitted to the Turks.

The Turk set out with all his forces, pitched his camp around this city, where he remained and laid siege. Time wore on, but the barbarian swore not to lift the siege until Dadibra surrendered. The siege stretched into four months, with no help from any quarter for the Dadibrenians. Through emissaries the emperor urged them to resist bravely, promising to fight along with them, but as he would always change his mind when he was on the verge of setting out, their adjoining neighbors, the Paphlagonians, did not dare to draw near and come to their aid. Then the besieged despaired of all succor. They were particularly distressed by famine and utterly ruined by the engines that discharged their stones from the hills outside into the middle of the city, demolishing the dwellings, hurling lime, and letting fly whatever else was deleterious for man; these shattered the water receptacles and ruined everything drinkable which stood and did not run.

Not long afterwards, an imperial auxiliary force commanded by three youths (Theodore Branas, Andronikos Katakalon, and Theodore Kazanes) arrived and encamped on Mount Babas. As soon as the Turks learned of this, they lay in ambush. Just before dawn, they attacked and pressed upon the fleeing Romans. They slew some and captured others alive, among whom were two of the commanders. The Turk led them around in a circle, with their hands tied behind their backs, and exhibited them to the defenders on the walls. He exhorted the defenders to hand over to him the helm of government while the city was not yet submerged by the waves of warfare; absolutely no hope remained that the city could be saved, or that he would depart unless he took possession of the city.

Their spirit broken by such spectacles and threats, the Dadibrenians turned to disadvantageous treaties dictated by the acute anxiety of the times and consented to abandon the city completely. Everyone was to depart unharmed, together with his nearest and dearest and his posses- sions, free to go wherever he liked, since the barbarian would allow no one to stay behind. He would not agree in any way whatsoever that they should pay him tribute. When these conditions were confirmed by oath, the Turk took possession of the city and gave it to his people to inhabit; the citizens left and dispersed throughout other provinces and cities. Many constructed wooden huts near their native city with the permission of the Turk and remained behind, putting on the yoke of slavery because the sweetness of their cherished city could not be wiped from their memory. Thus did the city of Dadibra meet its end. Shortly afterwards, the emperor made peace with the Turk [December 1196] and gladly paid the tribute that had been demanded before the fall of Dadibra as though he could quickly rub the disgrace of those times from his eyes.

The Roman empire had not yet spat out this brine and begun to lift up its head and enjoy a respite when it was buffeted by worse tidings; the future was to prove even more calamitous than the present, for if the partial loss of freedom was distressing, the attacks of the Western nations allowed us to envision the oppressive slavery that was to be imposed on our entire race.

Henry,1299 the ruler of the Germans, was the son of Frederick, who, as was recounted in the history of the reign of Emperor Isaakios Angelos, died on his way to Palestine while bathing for the last time in a river's stream. He took hold of his father's kingdom, and after bringing Sicily to terms [autumn 1194] and subjugating Italy, he turned his attention to the Romans, for he was unnaturally fond of revolutionary movements and an intractable evildoer. He forthwith lay in wait for the opportunity to attack the Romans, but not without hesitation, as he was daunted by the difficulty of the undertaking: the brave deeds performed by the Romans against the Sicilians when they had invaded our lands were still fresh in his mind, and he was no less restrained in his purpose by the pope of elder Rome [Celestine III].

Therefore, he dispatched envoys to Emperor Isaakios [February 1196] (for Isaakios had not yet been banished from the throne) and lodged complaints with the intent of creating an unjustifiable breach. As present ruler of Sicily, he laid claim to all the Roman provinces between Epidamnos and the celebrated city of Thessaloniki, which had recently bowed under the yoke of the Sicilian army by force of arms; its defeat and rout were due to Roman deceit-Henry was not the least of all those who spin pleasant fables. He enumerated the afflictions endured by his father, not only his recent troubles but also those with which he had had to contend over a long period of time because he had been removed from elder Rome, thanks to the cunning Emperor Manuel, and expelled from Italy as well. Unabashedly recalling events of the distant past, he demanded that the Romans purchase peace at a huge price or prepare to meet him it battle at once. In addition, he wanted to be designated lord of lords and proclaimed king of kings and insisted on succor for his compatriots, in Palestine with the dispatch of naval forces. The emperor replied in writing and sent a distinguished envoy; two envoys arrived in turn [before Christmas 1196], one of whom had bushy eyebrows and was remarkable for having been given the responsibility for the king's education as a child. Their negotiations centered around the payment of huge sums of money, false pretensions and boasts, and lists of their countrymen's glories with which they hoped to intimidate their audience.

Because the emperor whose reign we are now recounting could not dismiss the envoys empty-handed, he consented to pay money in return for peace, something which had never been done up to this time. Alexios, intent on extolling the wealth of the Roman empire, undertook no task suited to the times but did that which was neither worthy of respect nor seemly and which appeared almost ridiculous in the eyes of the Romans. On the feast of Christ's Nativity [25 December 1196], he donned his imperial robe set with precious stones and commanded the rest to put on their garments with the broad purple stripe and interwoven with gold. So astonished were the Germans by what they saw that their smoldering desire was kindled into a flame by the splendid attire of the Romans, and they longed the sooner to conquer the Greeks, whom they thought cow- ardly in warfare and devoted to servile luxuries. To the Romans who stood among them urging them to gaze upon the full bloom of the pre- cious stones with which the emperor was adorned like a meadow, to pluck the delights of springtime in the middle of winter and enjoy a feast for the eyes, they responded, "The Germans have neither need of such spectacles, nor do they wish to become worshipers of ornaments and garments secured by brooches suited only for women whose painted faces, headdresses, and glittering earrings are especially pleasing to men." To frighten the Romans they said, "The time has now come to take off effeminate garments and brooches and to put on iron instead of gold." Should the embassy fail in its purpose and the Romans not agree to the terms of their lord and emperor, then they would have to stand in battle against men who are not adorned by precious stones like meadows in bloom, and who do not swell in pride like beads of pearls shimmering in the moonlight; neither are they like the intoxicating amethysts, nor are they colored in purple and gold like the proud Median bird [the peacock], but being the foster sons of Ares, their eyes are inflamed by the fire of wrath like the rays of gemstones, and the clotted beads of sweat from their day-long toil outshine the pearls in the beauty of their adornment. In return for peace, the Germans demanded the payment of five thousand pounds of gold.

Spent by these negotiations, the emperor dispatched as his envoy to the king Eumathios Philokales, the eparch of the City [beginning of 1197], the wealthiest in the empire. Philokales willingly accepted the role of envoy and asked the emperor that with the insignia of eparch he also be granted those of envoy. The emperor was pleased to provide whatever traveling supplies he requested, but he must set out for the proposed journey at his own expense. Thus he stood out as an odd and eccentric envoy; not only was he not held in esteem compared with former envoys but he also drew derision down upon himself because of the strangeness of his dress.

Since the monies to be paid in exchange for peace came to about sixteen hundredweight of gold, Philokales waited in expectation of the gold's arrival in Sicily, where he met with the king. The emperor con- tended that he was in need of money and taxed the provinces, imposing the so-called Alamanikon [the German tax] for the first time. Convening the full number of citizens, the senate, and the clergy, as well as all those divided into different trades and professions, he demanded that contribu- tions be made and that everyone pay down a portion of his property. But he soon saw that he was accomplishing nothing and that his words were only empty talk. The majority deemed these burdensome and unwonted injunctions to be wholly intolerable and became clamorous and seditious. The emperor, blamed by some for squandering the public wealth and distributing the provinces to his kinsmen, all of whom were worthless and benighted,"" quickly discarded his proposal, as much as saying that it was not he who had introduced the scheme. Devising another plan, he claimed all the gold and silver votive offerings outside the sanctuary, as well as those that were not used to receive the Divine Body and Blood of Christ. When many recoiled from this, saying that he wished to defile the sacred, he resolved to rob the deaf and dumb tombs of the emperors, since they had no one to take up their cause. The tombs were opened, and they were stripped of every precious ornament. The only things left of those Roman emperors of old who boasted of glorious deeds were their coats of stone, those cold and last garments. Even the sepulcher of Constantine the Great would not have been spared, and the thieves would have stolen the splendid cover interwoven with gold which lay over it had they not been stopped by imperial decree. Collecting thence more than seventy hundredweight [seven thousand pounds] of silver and an amount of gold, the emperor consigned them to the smelting furnace as though they were profane matter. Two men from the imperial court who had been entrusted with the collection of these precious metals died shortly afterwards: one was consumed by a burning fever and the other, swelling up like a wineskin, succumbed to dropsy.

As for what followed-but who can worthily speak of the mighty deeds of the Lord or who shall cause His praises to be heard? News of the death of the king of Germany arrived before the dispatch of the monies [28 September 1197]. His death was received with great satisfaction by the Romans, and the Western nations were thrice-pleased, especially those that he had won over by force rather than by persuasion and those he was preparing to attack. He was ever racked by cares and opposed to all pleasures in his desire to establish a monarchy and become lord of the nations round about. Reflecting on the Antonines and the Augusti Caesars, he aspired to extend his rule as far as theirs and all but recited the words attributed to Alexander, "All things here and there are mine. Wan and solemn in aspect, he partook of nourishment only late in the day; to those who argued that it was his duty to take food to avoid cachexia, he replied that for a private citizen any time is suitable for eating, especially that which is accustomed, but as for a careworn emperor, if he wishes not to give a lie to his appellation of beloved, evening is time enough for indulging the body.

The death of the king of Germany, therefore, was, as I have said, prayed for by all the nations and more so by the Sicilians because when their island fell he inflicted a host of evils on them which cannot be easily set down in writing. They endured slaughter, suffered the confiscation of their monies, underwent the misfortune of banishment from their coun- try, and became subject to such excruciating tortures that death was preferable to life; in addition, many Sicilian cities were razed to the ground and important fortresses were demolished. To make sure that the Sicilians should never again long for freedom and rebel, Henry dashed their every fair hope, that which reposes in money, or chariots, or horses, and that which trusts in well-fortified city walls, in brave men, and in strong defenses. Henry, who lived in dread of the future and was unable to stave off the present, was plotted against by certain men but bested them. He did not avenge himself by putting them to the sword; rather, he first tortured them in many ways and then most pitiably took their lives. One he lowered into a cauldron of boiling water, placed in a basket like wheat, and then sent him on to his family; another he cast into a fire heated seven times more than usual;""' a third he placed in a sack and sent down into the deep. The initiator of the conspiracy, who was also chosen leader, he condemned to a much more violent punishment; ordering a crown made of copper with diagonal holes of equal size along the rim, he placed it with his hands on the rebel. He affixed the diadem with four huge pegs driven right through into the head, and as he walked away he said, "0 man, you have the crown which you wanted; I begrudge you not. Enjoy that which you so eagerly sought." The man reeled from dizziness and fell on his face and died soon afterwards, the thread of his life snapped by this pitiable crown.

At the fall of Sicily, Emperor Isaakios's daughter Irene was taken captive along with others [29 December 1194]. She was given in marriage to Philip [25 May 1197], the king of Germany's brother, born of the seed of fornication, after she had lost the husband of her virginity [Roger, d. 24 December, who ruled Sicily as tyrant after the death of his father Tancred [20 February 1194].

Although freed by the will of God from this great evil from which the whole of the Roman empire waited to suffer the worst horrors, another evil injurious to the public weal rolled in on the waves of the sea. A certain Genoese by the name of Gafforio constructed biremes and triremes and fenced himself about with round ships. With these he plundered the coastal cities and the islands which rise up in the Aegean Sea. He attacked Atramyttion as well and carried away booty and gathered riches beyond measure. At last the Romans, who were slow to deliberate on these matters, awakened as from a deep slumber and sent John Steiriones [Giovanni Stirione] against Gafforio with thirty ships. A native of Calabria, he was once a pirate, indeed the very worst of pirates; in return for lavish gifts, he had gone over to Emperor Isaakios and had benefited the Romans many times in naval battles. But when he sailed against Gafforio, he suffered an unexpected misfortune; having taken great care to outmaneuver his adversary, who commanded a larger force, he became the victim of the stratagem he had contrived from the very beginning. Gafforio stole upon the Roman ships as they were riding at anchor off Sestos at about midday. He found them emptied of their crews and seized them all, together with their arms and every living thing on board. From this time on, he attacked the islands with impunity, plundered the towns along the coast, and demanded and collected tribute as he pleased.

The emperor, who was confounded by these events, decided that it was necessary to come to terms with Gafforio. He dispatched some of Gafforio's Genoese friends (he had often put in at Byzantion for trade purposes and was fined money for the damages he inflicted by the dux of the fleet, Michael Stryphnos and initiated peace talks. He also made preparations for war, fitting out other triremes and again turning them over to Steiriones. He and Gafforio came to an agreement that the emperor would send six hundredweight of gold to Gafforio and apportion enough land to support seven hundred of his countrymen as men-at-arms; Gafforio, in turn, would submit to the emperor and obey his every command. While the peace was still in doubt, Steiriones, following the emperor's instructions, appeared unexpectedly before the enemy with his Pisan force. Engaging Gafforio in battle, he overpowered and killed him and seized his ships with the exception of four, one of which carried his nephew.

Once these evils were overcome, an upheaval in the palace greatly tarnished the emperor's government and brought long-lasting confusion. In describing these events, I shall first go back to the beginning in an attempt to clarify that which followed.

Emperor Alexios, as I briefly have remarked, before coming to power was deemed by most not a pacific man but a most bellicose one; hence everyone expected that he would stretch forth his lance against the enemies of the Romans and not be altogether tolerant towards his subjects. But once he became emperor, he appeared a different person to all, and by his actions he proved them all to be talking at random.

To make a long story short, lest I be guilty of saying too much and thus exposing my history to censure, as soon as he began his reign, he pro- claimed that the ministries were not to be auctioned off for money but would be awarded only according to merit. This notion was indeed most notable and admirable, the groundwork and base and foundation of an auspicious reign; even if one chooses to find parallels, neither in the distant past nor in recent times could one find such an example as in our own days. All the emperor's relatives were avaricious and grasping, and the frequent turnover of officials taught them nothing else but eagerly to steal and loot, to purloin the public taxes, and to amass great wealth. The petitioners who came to them because of their influence with the emperor they despoiled, and the monies collected, huge sums that surpassed any private fortune, they appropriated for themselves.

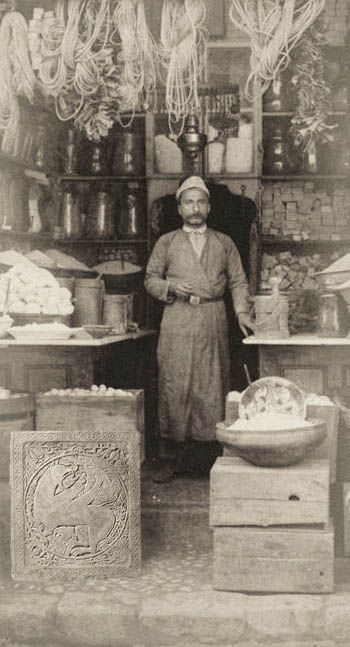

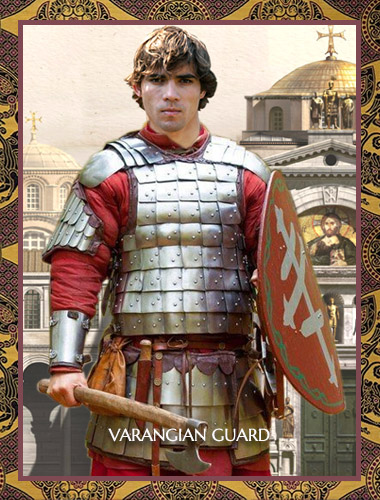

As a result of these conditions, Alexios failed in all else, more so than any other emperor, and the ministries went from bad to worse; once again they were offered for sale to those who wanted to buy them. Any- one who so wished could become governor of a province and receive the highest Roman dignity. Not only were the baseborn, the vulgar, the moneychangers, and the linen merchants honored as sebastoi, but Cumans and Syrians found that they were able to pay money for the dignity of sebastos, which was held in contempt by those who had served previous emperors.

As a result of these conditions, Alexios failed in all else, more so than any other emperor, and the ministries went from bad to worse; once again they were offered for sale to those who wanted to buy them. Any- one who so wished could become governor of a province and receive the highest Roman dignity. Not only were the baseborn, the vulgar, the moneychangers, and the linen merchants honored as sebastoi, but Cumans and Syrians found that they were able to pay money for the dignity of sebastos, which was held in contempt by those who had served previous emperors.

The primary cause of all this, as I have said, was the light-mindedness of the emperor and his ineptness in governing the affairs of state; of no less importance was the greed of those around him and the insatiable, unquenchable, desire of some to amass money by which the affairs of state became the sport of the women's apartments and the emperor's near male relations. Alexios knew no more, in fact, of what was going on in the Roman empire than did the inhabitants of ultima Thule.1315 The pilot of the ship of state, therefore, was ill-spoken of by all, and the officers he stationed in command at the bow and the crew were subjected to the most abominable curses.

The empress deemed the situation to be intolerable, and as nothing could escape her inquisitiveness and her love for money, she decided she could not voluntarily keep quiet for long; either the appointments to office were not to be sold by the command of her husband or the monies collected must be stored in the imperial treasury. First of all, the empress appointed as her minister, Constantine Mesopotamites; it was he who exercised the highest authority under Isaakios Angelos, as we have recounted in the chapters dealing with his reign. Later, Alexios achieved a reconciliation with Mesopotamites, who, before Alexios came to power, looked upon him with disaffection and who continued to turn his face from him even after he ascended the throne because he had instigated the Romans to rebel against the present state of affairs and progressively and ceaselessly had confounded and thrown everything into confusion.

As the administration of public affairs again devolved upon Mesopotamites, the authority of others was extinguished and the light of domination of those attached to the emperor was dimmed. He, who formerly was looked down upon as refuse by the emperor, was now deemed to be incomparable, the horn of plenty, the mixing bowl of many virtues, or all the herbage of Job's field."" He knew how to accommodate himself to every situation; light was shed from his eyes, and life-giving air poured into his nostrils; he was the genuine pearl of Peroz1319 ever hanging from the emperor's ears, considered worth the entire realm, a veritable Artemon the notorious, Argos the many-eyed, and Briareus the hundred-handed.

Others bore this unexpected turn of events grievously, especially those who had fallen from power and whose light, like that of glowworms, turns dim at the break of day. The empress's blood relations, Andronikos Kontostephanos, who was married to her daughter Irene, and her brother Basil Kamateros,132222 were choked with rage. Disregarding the stone that had been cast against them then, and which lay as a stumbling stone 1323 (1 speak of Constantine Mesopotamites), they directed their efforts and vented all their wrath against the empress who had discharged it and sought an opportunity to quench their thirst for revenge.

After giving considerable thought to what should be done, after care- fully deliberating and plotting, they approached the emperor, who was about to set out for the western regions. On this day, they met with him and said, "Although nature recognizes kinship as being more honorable and deserving of affection, we wish to be, and to be known as, the emperor's friends or as Alexios's friends, rather than as Euphrosyne's friends. For the common salvation of all men, that is, the salvation of the empire, and for our own good, it is necessary that you suffer no harm from human hand; should anything unexpected happen to you, we shall fall with you and suffer the same calamities, deprived of all the things with which we were furnished during your reign."

Thus prefacing their remarks and dexterously tuning the strings of the lyre of speech, they gave the finishing argument of their harangue like some melody that would drive the emperor out of his mind and change his appearance into that of a madman, even more than the musical airs of Timotheos which inspired Alexander of old when he was preparing for war. They asserted, Your wife, 0 Despot, with unveiled hand perpetrates the most loathsome acts, and as she betrays you, her husband, in the mar- riage bed as a wanton, we fear lest she soon instigate rebellion. The confidant with whom she rejoices licentiously to lie, she has likely chosen to become emperor and is bent upon achieving this end. It is necessary, therefore, that she be deprived of all power and divested of her great wealth. Her lover, whom you have officially adopted and whom, in transgression of the law, she has made her stud, must be removed forthwith, without delay, in order to bring an end to this defilement. The punishment of your iniquitous wife should be delayed until the time that, with God's help, you have concluded your present business and have returned to Constantinople.

Having thus spoken and offered their counsel, they were listened to as the dearest of friends and as though they were a rare and welcome treasure. The emperor, greatly troubled1325 that such should be his reward forthe benefactions bestowed on Vatatzes, immediately dispatched one of his bodyguards, by the name of Bastralites, and put Vatatzes to death.

Vatatzes was residing in the regions of Bithynia that still contended against Alexios the Cilician. When Bastralites arrived there, he led Vatatzes away from the camp so that no one should hear and reveal the secret orders he had brought from the emperor. Then he unsheathed his sword, and his assistants made ready to commit murder; the youth was thereupon dismembered like a fatted calf. All the troops were grieved and sorely vexed by this deed, especially those before whose very eyes the act was perpetrated. Bastralites placed Vatatzes head in a pouch and returned well-girded to the emperor. When the head was thrown at his feet, the emperor kicked it, and, gazing at it for a considerable length of time, he then addressed it in terms wholly unfit to be included in this history.

Following this episode, the emperor continued on his way and set out for Kypsella [February or July 1197] to bring deliverance to the Thracian cities which were ravaged by the Vlachs and Cumans; moreover, he proposed to seize Chrysos [Dobromir] or at least to check his furtive incursions and his despoiling of the lands round about Serrai.

This Chrysos, a Vlach by birth and short in stature, had not conspired with Peter and Asan in their rebellion against the Romans since, as an ally of the Romans, he was expected to take up arms against them with the five hundred countrymen under his command. Not long afterwards, he was seized for leaning towards his fellow Vlachs; ever pressing ahead and canvassing to become ruler, he was put in prison. When he was released and sent by the emperor to defend Strummitsa, he betrayed his hopes, and in taking up his own cause he, too, became an inexorable evil for the neighboring Romans.

The emperor therefore moved rapidly against him and assembled a considerable army at Kypsella, but he shrank from his objective in his desire to return home; in vain he had gathered the troops and for naught had he made his way to Kypsella. He left the western regions to fend for themselves and. suffer as before, while he returned to Byzantion having spent less than two months in the field.

At first he quartered in the palace at Aphameia, and afterwards moved into the Philopation. Empress Euphrosyne, collecting her wits, grasped the meaning of the accusations made against her and feared her husband.; She stretched out her hands to all with a piteous and subdued expression, entreating those who had the emperor's confidence to succor her and to speak loudly in her defense not only because she ran the risk of being expelled in disgrace from the palace but also because it was quite obvious that her very life was in danger. The majority took pity on her. One party urged the emperor to pay no heed to the charges leveled against his wife and furthermore calumniated her accusers, calling them prickly in manner, stitchers of falsehood, crooked in speech, and even captious and querulous; another group counseled him with great forethought what to do so that later he not be found taking back the wife whom he had put away now as an adulteress; thus bringing down dishonor upon himself, he would become the subject of common gossip, comparable to those ani- mals which brandish the weapons on their foreheads but when provoked do not gore their rivals who are covering their females before their very eyes.

Later, when he entered the palace of Blachernai, he did not at once vent his wrath, but as he admitted his wife for one last time to take dinner with him, his inner agitation showed in his angry countenance and in the manner in which he turned his eyes away from her; inflamed by the fire of anger, yet not consumed by it, or burning secretly within and extinguishing the flame without being detected, he never again consorted with her or dined with her. She, in turn, demanded to be placed on trial for the charges made against her, asserting that she was willing to suffer whatever judgment was made against her. She entreated the emperor to disregard the ingenious inventiveness of her accusers and his kinship with them and to give heed to the accuracy and truth of the matter. He did not follow any such course of action but instead subjected certain of the female chamberlains to torture. Ascertaining from the eunuchs of the bedchamber precise details of the affair, he commanded some days later that she be removed from the palace and divested of her imperial gar- ment and splendid robe. She was led out of the palace through a little-known descending passageway dressed in a common frock, the kind worn by women who spin for daily hire, escorted by two barbarian handmaids who spoke broken Greek. Thrown into a two-oared fishing boat, she was taken to a certain convent, built near the mouth of the Pontos, named Nematarea.

After the empress was disposed of in this manner, her accusers experienced some discomfort, for in their too forceful attempt to neutralize the empress, they had vilified her before the emperor; it was not their wish to expel her entirely from the throne or completely to undermine its very foundations. They had never expected the emperor to act so drastically against her, looking to his softheartedness and his ability to remain cool-headed. They who brought shame upon their family were grieved, although they were not as distressed as they should have been; and the reproaches and taunts cast upon them by the populace pressed hard upon them. Six months had elapsed [October 1197 to March 1198], and the empress Euphrosyne remained banished from the palace. She would have been ignored until the very end had not they who had wounded her also healed her, but not in the manner that Achilles healed Telephos;1332 in- stead, the universal hatred against them for having brought disgrace to her who had honored them impelled them to find a way in which she could be restored. While all the emperor's kinsmen were of one mind and persisted in their efforts to topple Constantine Mesopotamites from the tightrope he walked, Euphrosyne was reinstated forthwith and became more powerful than ever. She did not openly express her exceeding wrath against her adversaries, neither did she lay snares for the sake of revenge, nor was she so possessed by anger that like Medea she was goaded to Bacchic frenzy against them. She tamed her husband like some wild animal, and since it was a long time since he had shown her any affection, nor had he gone to bed with her, she cleverly insinuated herself into his good graces, choosing to wheedle him with cunning. In this way, she took over almost the complete administration of the empire. Such then was the outcome of these events.

Constantine Mesopotamites (for more must be said about the Proteus of our times, this extremely wily and versatile man) put on airs and walked mincingly upon the empress's return. It was for this reason, I think, that he believed that he could do anything with the emperor and forthwith rejected the honor of being promoted to the office of keeper of the inkstand as being both inadequate to his station and too small to contain the magnitude of his power. He preferred instead to be ordained from lector to deacon, as he was unable to endure that anything, even holy orders, should be outside his reach. His request was immediately granted. The emperor himself went down to the celebrated church in Blachernai, and as soon as the patriarch arrived, he promoted Mesopota- mites from lector to deacon, and he was granted the preeminent standing and degree in rank. Having accomplished this, he assumed a posture of one in decline and never again appeared at the palace or served the emperor in any capacity whatsoever; the canons do not allow priests to be both consecrated to God and involved in secular affairs in any way, for both are distinct and can never coalesce because to serve God and mam- mon is a contradiction."" But the emperor clung to him like ivy. With his hands around a tome which he displayed forthwith, he compelled Patri-arch Xiphilinos to allow Mesopotamites to serve both God and emperor, church and palace, without suffering the penalty for violating those can- ons which sharply discipline this double life [before 7 July 1198]. This, too, was done, and shortly afterwards he was appointed archbishop of the most splendid city of Thessaloniki.