t

t

From the most pious Irene we proceed, after a passing glance at the half-dozen Empresses of less fame who come between them, to a notable Empress whose memory has actually been enshrined in the list of the canonized. Byzantine piety has at times assumed such peculiar features in the course of our story that we will not leap to the conclusion that at length we reach a woman in whom modern taste will find a realization of its standards. The restoration of the images of the Virgin and the founding of monasteries were in those days arguments powerful enough to silence the importunities of the devil’s advocate. Theodora will be found to have ways that the modern woman may or may not admire, but will assuredly not be encouraged to imitate. Yet it will be something to meet a powerful Byzantine Empress whose hands are not stained with blood, and, from her romantic elevation to her tragic fall, the story of Saint Theodora will prove of no little interest.

We have left Irene dying of a broken heart in her island prison while the perfidious Nicephorus wantons on her wealth in the sacred palace. Since no wife is associated with him in the chronicles, it is not ours to determine whether he really was “the sink of all the vices,” as the ecclesiastical writers say, or whether his anti-clerical spirit and his refusal to persecute heretics have not loaded the scales against him. The example of Charlemagne, who maintained an imperial harem in the heart of Christendom, seems to have affected him. When he had commanded (for his son Stauracius) one of those “beauty shows” by which the Byzantine Court often selected a royal bride, and three blushing and beautiful maidens were presented for his final decision, he is said to have appropriated two of them and imposed the third on his son. The new Empress, Theophano, was an Athenian girl, a relative of Irene, but, though she was not devoid of ambition, Fate did not afford her the opportunity enjoyed by Irene. Nicephorus fell in war after a reign of nine years, and his skull, tastefully mounted in silver, became a favourite drinking-cup of the King of Bulgaria. But his son Stauracius was gravely wounded in the same battle, and was borne back to the city in a litter in a dangerous condition.

Theophano, who was childless, saw the crown slipping from her hands as soon as she had obtained it. The Emperor’s sister Procopia was married to the chief governor of the palace, a very handsome, amiable, black-haired youth, not wanting in popularity, and the soldiers and Senators whispered too loudly that he was fit to wear the purple. Stauracius, from his sickbed, petulantly ordered that the bright eyes of Michael should be cut out, and that the imperial power should pass to Theophano. Within a few weeks the army turned upon its helpless sovereign, and lodged him in a monastery. Theophano passed from the palace to a nunnery and lost the beautiful hair which had so recently helped to win her a throne; but it should be added, for the credit of Michael, that he enabled her to soften the disappointment with all the comfort that a large fortune could afford a woman with sacred vows.

Even more romance is packed into the brief story of the Empress Procopia. Rising with her father, Nicephorus, from the level of court officials to the imperial rank, she had married the handsome superintendent of the palace and had, after a fortunate escape from the vindictiveness of her brother (or of Theophano), been crowned mistress of the Roman world, in the gold-roofed triclinon on 2nd October 811. To her the Fates seemed103 to open a long and glorious career. Her husband had neither grit nor judgment, and she virtually undertook the administration of the Empire. Unhappily, she illustrated in a fatal degree the proverbial subservience of women to priests and monks. The policy of Nicephorus was reversed; the Church smiled under a shower of gold, while the heretics were lashed into sullen defiance in the provinces. Officers and nobles looked with disdain and irritation on this revival of clericalism, and even concerted a plot to bring the eyeless sons of Constantine VI. to the throne from their distant priestly homes. When, in the year 812, Procopia drove out at the head of the troops, who were marching against the Bulgarians, the soldiers murmured and the “simple-minded” Michael, as a contemporary calls him, was insulted. And when, in the following spring, Michael, relying on his spiritual advisers for carnal warfare, was ignominiously beaten by the Bulgarians, the soldiers offered the crown to a vigorous Armenian officer and marched on the city.

Thus in less than two years Procopia forfeited the power which, she believed, she had used so admirably. Her mild and timid husband returned to the capital to tell her that he proposed to resign and avoid a civil war. She raged in vain at his pusillanimity; the chroniclers tell us, in particular, that she dwelt with strong invective on the notion of this unlettered officer’s wife appearing in the purple. While they discussed, the army reached Constantinople, and they fled, with their children, to a chapel in the palace grounds near the sea. The end was ruthless and inevitable. Michael, who was little feared, was clothed with the monastic habit which befitted him, and placed on one of the Princes’ Islands, in the Sea of Marmora, from which so many kings and princes were to gaze upon the palace they had lost. His elder son was castrated. Procopia was shorn and clothed with the hated black dress of a nun, and, deprived of all her property, she lived for a few miserable years with her daughters in a convent on the fringe of the city.

The Empress Theodosia, wife of Leo the Armenian, who now ascended the throne, hardly merited all the disdain with which Procopia had depicted her in the imperial robes. She was the daughter of Arsaberes, an officer and patrician of such rank and culture that there had been an attempt to put him on the throne in the reign of Nicephorus. One of the chroniclers, however, speaks incidentally of Leo’s “incestuous marriage,” and we may assume that there was something wrong in the connexion. It matters little, as Theodosia remains in complete obscurity during her husband’s seven years’ reign. Only in the last week does she make her first, and last, appearance in history.

In spite of a sincere desire to reform the Empire, and the most energetic measures to purify and strengthen it, Leo became unpopular. Reformers were rarely popular at Constantinople, and Leo had the additional disadvantage of favouring the Iconoclasts. When fiery monks denounced his maxim of universal toleration, he resorted to violence, and hands and feet began to fall under the axes of his soldiers. At last he discovered that the Count of his guards, Michael, was at the head of a conspiracy, and he is said—many historians refuse to believe the statement—to have ordered that Michael be cast forthwith into the furnace which heated the baths of the palace. It was Christmas Eve, and the Empress was horrified to learn that the feast was to be desecrated in this way. As the soldiers conducted Michael through the palace, she rushed from her bed, with flying locks and disordered dress, and fell upon Leo “like a bacchante.” He sullenly postponed the execution, muttering: “You and the children will see what comes of keeping me from sin.” Michael was fettered and confined, and Leo retired with the key of the fetters in his breast.

The unknown story of Theodosia, daughter of Arsaberes,105 ends in a thrilling page of romance. Leo slept little, the fear that he had blundered tormenting him, and at last he went in the dead of night to the chamber in which Michael was confined. To his surprise he found Michael sleeping on the jailer’s bed, instead of being chained to the wall. He retired to consider the matter, but it seems that he took no steps, and, in the early morning, he went to the chapel to chant matins with the clergy. Now a page, who had been lying in a corner of Michael’s cell, had noticed the purple slippers of the man who had entered; he at once wakened Michael and his friendly jailer, and a message was hastily sent to friends in the city, threatening to betray them to Leo if they did not deliver Michael at once. It was, as I said, the depth of winter—it was now Christmas morning—and a group of singers were to enter the palace in the early hours to join with Leo in singing the service. Leo had a resonant voice, of which he was very proud. With these singers, hooded and cloaked with fur, the conspirators mingled, and made their way to the chapel, concealing their swords. They stood perplexed in the dim and cold chapel, as Leo had drawn his fur hood over his head and was unrecognizable, until at last his sonorous voice rang out, and their swords gleamed in the light of the lamp. Leo, a very powerful man, seized the cross, and defended himself for a time, but soon fell dead to the ground. Theodosia was turned adrift in the desolate Empire, her four boys were castrated—one dying under the brutal mutilation—and Michael the Stammerer, instead of passing to the furnace, sat on the golden throne, even before the fetters could be struck from his feet.

The reign of Michael introduces us at length to the woman whose name stands at the head of this chapter. Michael was the son of a Phrygian peasant, knowing more about pigs and mules than about Greek letters, says the indignant chronicler, and had risen from the lowest rank of the army. He had in early years married the106 daughter of an officer; though we may smile at the legend that Thecla was bestowed upon him because some soothsayer had foretold his fortune. Thecla had enjoyed a year or two of splendour and passed away, leaving a son and daughter. Second marriages were not favoured by the clergy and monks, and it is said that Michael secretly arranged with the Senators that they should press him to marry again; but when we find that he married a nun, we can hardly suppose that he was disposed to fear the clergy. His second Empress, Euphrosyne, has made no mark in history, yet she is interesting. It will be remembered that twenty years earlier the son of Irene had divorced his wife Maria, and sent her and her young daughters into a convent. It was one of these daughters who, after spending twenty years’ placid existence in a religious house during all the storms that had swept through the palace, was recalled to the world, relieved of her vows by the patriarch, and married to the boorish Michael. After four or five years’ further enjoyment of the palace, Michael was carried off by dysentery, and left the Empire to Euphrosyne and her stepson Theophilus. Here begins the story of the sainted Theodora, and ends the brief visit of Euphrosyne to the brighter world.

When Theophilus ascended the throne in 829 he is said to have been a widower, though still young. The chroniclers persistently state that the youngest of his five daughters married one of his officers a few years after his accession, and the only solution of this singular puzzle is said to be that an earlier wife had died and left him with several girls. He was not, at all events, married when he was crowned in 829, and, with the aid of Euphrosyne, he sought a consort. Once more matrimonial commissioners searched the city and the provinces, and every father of a beautiful girl hastened to display her charms to the imperial examiners. Some writers would confine the scrutiny to the city of Constantinople, but the fact that Theodora came from the107 distant province of Paphlagonia confirms the statement of George the Monk that the imperial commissioners travelled through “all regions” (of the Empire) in search of a perfect bride. The utmost that panegyric has been able to say of Theodora’s parents, Marinus and Theoclista, is that they were “not ignoble.” We may assume that, like the Empress Maria, the mother of Euphrosyne, she was discovered in some obscure village of Asia Minor and conducted, with fluttering heart, to the Court of the great king.

Euphrosyne added a picturesque feature to the “competition.” She arranged the élite of the candidates in a line in the hall of one of the palaces, gave Theophilus a golden apple, and bade him give the apple to the lady of his choice. He first approached a maiden named Casia, or Cassia, who was not only the most beautiful of them all, but had some repute for poetical talent. “How much evil has come through woman,” said the imperial prig, improvising a Greek verse. “Yet how many better things have come from woman,” the young poetess modestly retorted, in verse. To her great mortification he passed on, apparently displeased with her ready tongue, and gave the apple to Theodora. Casia retired to a nunnery and to the composition of hymns, and Theodora was, on Whitsunday 830, married and crowned by the patriarch Antony in the historic chapel of St Stephen.

Euphrosyne returned to her convent immediately after the coronation. Some authorities say that she was dismissed by Theophilus, others that she retired voluntarily. It is not improbable that twenty years of religious life had made her a real nun at heart, and she retired the moment she was relieved of those reasons of State which had interrupted her solitude.

During the thirteen years of the reign of Theophilus the Empress bore her children and confined herself to the gynæceum, as a good Empress should. Two sons and five daughters are assigned to her, but, as I said, some,108 if not all, of these daughters of Theophilus seem to have had an earlier mother. Maria is described as the youngest, yet about the year 832, two or three years after the marriage of Theodora, she married the commander Alexis. She died shortly afterwards.

Theodora had been piously educated in the orthodox faith, and it is piquant to read the approving language of the religious writers when they describe her duping her husband and breaking her oath to him. Cardinal Baronius, who is endorsed by the Bollandists, calls her “the glory and ornament of holy womanhood ... the unique example of exalted holiness in the east.” We shall follow these distinguished authorities on sanctity with some hesitation when we afterwards find Theodora encouraging her son in vice, in order that he may leave the administration to her and the clergy, and permitting him to hold drunken suppers with his mistress in her palace; but the worldly minded biographer must be less enthusiastic than they even about her earlier actions.

The first anecdote told of her is that the Emperor one day noticed a heavily laden ship making for the port of Constantinople and learned that it belonged to Theodora. He went down in great anger to the quay, and ordered the ship and its cargo to be burned. “God made me an Emperor,” he cried, “and my wife and Augusta has made me a shipowner.” The Bollandists merely enlarge at this point on the naughtiness of princes who wish to monopolize trade for their own profit, but I think that a better defence of Theodora can be imagined. The young Empress was probably blameless. It was a custom of courtiers to evade the duties on imports by trading in the name of the Empress, and Theodora would hardly understand the matter sufficiently to refuse her name at once.

The genial critic will also regard with some indulgence her petty mendacities in regard to the beloved images which she cherished in secret. One day her jester, or half-witted page, came suddenly into her room and found109 her embracing the forbidden statues. She told him that they were dolls, and Denderis went at once to tell Theophilus of the pretty dolls with which his wife played in secret. Theophilus angrily started from the table and went to her room. The fool was mistaken, she cried; she and her maids had been looking in a mirror, and the boy had taken their images in the mirror to be dolls.18 Theophilus was not convinced. Little more could be learned from the page, who had been flogged by Theodora and told to hold his tongue about dolls, so that whenever Theophilus asked him, he said: “Hush, Emperor; nothing about dolls.” But his young daughters also now began to speak of dolls, especially when they returned from visits to Theodora’s mother, who had a palace at Gastria across the water. He learned from them that the old lady kept a chest full of pretty dolls, which they were encouraged to kiss and embrace when they visited her. The visits were immediately stopped, and Theodora was compelled to take the most sacred oaths that she would never favour the worship of images. Like Irene, she did so with mental reservation.

The long and vigorous reign of Theophilus ended sadly. Unsuccessful in war, indiscreet at home, and at war with the clergy, he wasted his talent in adding to the luxury of the Court. He found a wonderful mechanic and engaged him to fill the palace with expensive toys that seemed to enhance the imperial dignity. Before “Solomon’s Throne” in the Magnaura palace were set lions of gilded bronze which would rise and roar at the approach of foreign ambassadors. Golden trees, with golden singing birds, invisible organs, and all kinds of mechanical barbarities were added to the rare furniture of the palace. New palaces also were built in the grounds: a semicircular hall with roof of gold and doors of bronze and silver, fountains which gave aromatic wine from their silver pipes on feast-days, summer palaces and chapels completely lined with the choicest marbles and mosaics. A superb palace was raised on the Asiatic shore in imitation of the Caliph’s palace at Bagdad, and the palace at Blachernæ, in the cool northern suburb, now spread over a vast domain. But with all this facile splendour Theophilus was conscious that he failed to hold the ever-pressing enemies of the Empire, and he became morose and diseased. Theodora seems to have kept his affection to the end. In an earlier year she had detected him in criminal intimacy with one of her maids, and he had asked her forgiveness with great humility. His last act was a brutal murder in her interest. The noble Theophobos, who was married to the Emperor’s sister Helena, was in jail on some suspicion. Theophilus feared that he might aspire to the throne, and ordered the head of the unfortunate noble to be brought to him. He died in January 842, leaving the Empire to Theodora and her infant son Michael.19

Theodora now had supreme power, and her first care was to restore the worship of images, in spite of her heavy oaths to Theophilus. In this she needed diplomacy, as well as casuistry, since the learned patriarch John, as well as the majority of the Senators, were opposed to images. There was, moreover, a Council of Regency, consisting of three of the abler officials of the Court. The first of them, Theoclistos, the eunuch “keeper of the purple ink,” was an official of some ability, and so devoted to Theodora that, in spite of his condition, the gossip of the city associated the saint and the eunuch in a most unedifying manner. The second member was Manuel, an uncle of Theodora and an Iconoclast; the third her brother Bardas, a man of equal ability and unscrupulousness, who could be relied upon either to worship or to break an image according to his interest. It was to this man, in spite of notoriously immoral life, that Theodora entrusted the tutorship of the young prince; and there cannot be the slightest doubt that Michael was deliberately educated in vice and sensuality, in order to divert his attention from political power. St Theodora was to be the mother of the Nero of the Eastern Empire.

The first step was taken in the restoration of images shortly after the beginning of the Regency. Michael fell dangerously ill and at one time he was believed to be dead. The monks came from the great monastery of Studion, the most fiery centre of orthodoxy, to pray over the remains of the Iconoclast—a singular procedure—and it was presently announced that he had miraculously recovered his life and was converted to the worship of images. In this new zeal he pressed the Empress to remove the impious restriction on piety, and for a time she resisted, pleading the sanctity of her oath. Knowing Constantinople as we do, we have little difficulty in regarding the whole procedure as a comedy. At length a council was summoned in the house of Theoclistus, and the reform was sanctioned. The patriarch John was now ordered to convoke a synod; he refused, and the way in which that obstacle was removed so well illustrates the character of Constantinople, if not of Theodora, that it is worth describing.

John was one of the most learned men of his time, a genius in physical science and mechanical art. His rationalistic opposition to the popular cult of relics and statues, however, gave a dark aspect to his learning, and he was commonly regarded as a magician and a secret libertine. Men told each other of the subterraneous chamber which he had in his brother’s house for entertaining nuns and other pretty women. In reality, he seems to have been a learned and conscientious man, and, even when Bardas cruelly flogged him, he refused to submit to the Empress’s wish and relieve her from her oath. The report was given out from the palace that he had inflicted the marks of the scourge on himself, and had even attempted to commit suicide. He was at once deposed and confined in a monastery; and, when it was reported to Theodora, no doubt falsely, that he had there pricked the eyes out of a picture of Christ, she angrily sentenced him to lose his own eyes and to receive two hundred strokes of the loaded scourge. He had been one of the chief pillars of her husband’s reign. His friends, I may add, retorted by accusing the new patriarch Methodius of rape, but decency prevents me from describing how the archbishop happily escaped the charge by proving, in open court, that St Peter had miraculously relieved him from temptations of the flesh many years before.

The new patriarch convoked a synod, and crowds of monks flocked to Constantinople from all parts to encourage the good work, and marched through the streets of Constantinople under their sacred ensigns. Theodora surprised the bishops and abbots, as they sat in conclave, by demanding that they should issue a guarantee that her husband was absolved from his sins. It was a dangerous precedent, and they protested that they had no power to give such an assurance. Theodora then explained that she had presented a sacred image to Theophilus in his last hour, and that he had embraced it fervently. Modern historians are ungallant enough to disbelieve her story, and no doubt there were many at the time who distrusted Theodora’s casuistic ability, but when she proceeded to hint that image-worship would not be restored unless they satisfied her, they decreed that the sins of Theophilus had been undone by repentance. At the conclusion of the synod Theodora entertained the holy men in her Carian palace, or palace built entirely of the famous Carian marble, at Blachernæ. Near the end of the banquet, when the cakes and sweets were being served, her eye fell on the grim, disfigured face of the religious poet Theophanes. He had come from Palestine to Constantinople, during her husband’s reign, to fight for the images, and Theophilus had sent him into exile with no less than twelve lines of bad verse tattooed on his face, announcing that he was a “wretched vessel of superstition.” Theophanes marked the tearful gaze of the Empress, and impetuously cried that he would not forget to ask the judgment of God on Theophilus for the outrage. “Is this the way you keep your promise?” she exclaimed excitedly; and the bishops had to intervene and appease her and the martyr.

This restoration of image-worship seems to be the one virtue which ensured for Theodora a place in the Greek canon of the saints (on 11th February). That she led a chaste life we need not doubt for a moment. The rumour of amorous relations with Theoclistus is foolish gossip, and a man named Gebo, who afterwards claimed to be her natural son, was either an impostor or a lunatic. But the shallowness of her piety and weakness of her moral character are too plainly revealed in the debauching of her son by her own brother, into whose care she gave the young Emperor. The historian Finlay observes that “in the series of Byzantine Emperors from Leo III. to Michael III., only two proved utterly unfit for the duties of their station, and both appear to have been corrupted by the education they received from their mothers.” When we reflect on the strange types of men whom the disordered life of the Empire brought to the throne, this is a terrible impeachment of Irene and Theodora; and it is a just impeachment. No man was less fit than her brother Bardas to train a youth, and the only conceivable palliation of Theodora’s guilt is that she wished to retain power in the interest of the Church. How even that hope was mocked, and the rule of her son ended in debauchery and murder in her own house, we have next to consider.

For some ten years the Empire enjoyed comparative peace and prosperity. The Bulgarians, learning that a woman and a child ruled the Empire, made inflated demands, but Theodora met them with admirable firmness, and averted war. Her only grave blunder was the ruthless persecution of heresy. She sent officers to convert the masses of Paulicians in the eastern provinces, and, whether with her consent or no, they perpetrated horrible butcheries in the name of religion and engendered a civil war. Then, as Michael approached his sixteenth year, a series of terrible internal troubles and disorders set in.

Gladly following the example of his tutor Bardas, the young Emperor fell in love with the beautiful daughter of a high official of the Court named Inger. Eudocia Ingerina is described by one of the writers of the Court of Constantine VII.—her grandson—as “one of the most beautiful and most modest women of her time.” The course of this narrative will show that she was, as most of the chroniclers say, one of the most dissolute women of the time, second only to Theodora’s daughter Thecla. Whether she betrayed her laxity even at this early age, or whether Theodora merely dreaded an alliance of her son with a distinguished officer, we cannot confidently say. The chroniclers suggest that she was already the lover of Michael, and that Theodora and Theoclistus interfered. They compelled Michael to marry another Eudocia, daughter of the patrician Decapolita. We do not know the fate of this lady and may trust that she did not live to see the more sordid phases of her husband’s life. It seems that very shortly after the marriage he resumed his relations with the daughter of Inger.

Bardas now began to force his ambition more openly and get rid of the members of the Council of Regency. He first, by means of Theoclistus, drove his uncle Manuel into private life, and then turned upon Theoclistus, who ventured to remonstrate with him about his notorious liaison with his own daughter-in-law. Fearing for his life Theoclistus built a house close to the palace, communicating with it by an iron door, which was carefully guarded, and continued to administer the Empire in conjunction with Theodora. There is some indication that Theodora’s three sisters—Sophia, Maria and Irene—also had some share in the administration. Bardas pointed out to his pupil that he was improperly excluded by them, and suggested that Theodora intended to marry Theoclistus and have Michael’s eyes put out. When, therefore, Theoclistus next went to read his report to Theodora, he was intercepted by a group of the servants of Bardas, who, in the name of the Emperor, demanded his papers. A scuffle took place, and Theoclistus was imprisoned, and presently murdered in his cell. One of the chroniclers would have us believe that one of Theodora’s daughters actually witnessed the murder on behalf of her brother.

Theodora was beside herself when the news reached her that her favourite minister had been murdered. She is described as roaming about the palace with dishevelled hair, weeping and upbraiding her son and brother. The natural result was that they decided to remove her, and she saw that her rule had come to an end. She summoned the Senators and laid before them a financial statement of the affairs of the Empire. She had so well husbanded the funds left by Theophilus that a store of gold and silver amounting to many million pounds of our coinage, besides chests of jewels and other treasure, were at the disposal of the State. “I tell you this,” she shrewdly added, “in order that you may not readily believe my son the Emperor if, when I have quitted the palace, he tells you that I left it empty.” She saluted the Senators, laid down her power, and quitted the imperial palace. But Michael and Bardas were not116 content. As Theodora and her daughters went to the palace at Blachernæ they were arrested by her elder brother Petronas, shorn of their hair, and confined, in the dress of nuns, in the Carian palace at Blachernæ. They continued, however, to regard the proceedings at Court with close interest, and were transferred to the palace-monastery of Gastria across the water.

From her near exile Theodora watched the next dramatic phase of the quarrel. It was in the year 856, apparently, that Theoclistus was murdered and she forced to resign, and the next ten years witnessed a repellent development of Michael’s vices. He has passed into history under the name of Michael the Drunkard, but drunkenness was not the worst of his vices. He lived in open association with Eudocia Ingerina and filled the palace with scenes that had been banished from Roman life with the death of Nero. The only point that can be urged in favour of Byzantine morals is that the drastic legislation and action of earlier Emperors had checked the spread of unnatural vice. Apart from this, Michael the Drunkard ranks with Nero and Caligula, and, in respect of some kinds of grossness, surpasses them. Only the more repellent pages of Zola’s “La Terre” offer an analogy to the coarse practices which Michael rewarded in the abominable circle he gathered about him. It is enough to say that the filthiest of his friends dressed in the vestments of the archbishop, and had eleven followers dressed as metropolitan bishops; that they used the sacred vessels, with a mixture of mustard and vinegar, for their parody of the Mass; and that they paraded the streets on asses in this guise, and hailed the patriarch himself with obscene cries and gestures. The treasures left by Theodora were soon dissipated on these ruffians and on Michael’s favourite charioteers, and the golden curiosities made by Theophilus were melted down to eke out the failing exchequer. And when Michael was told that the enemies of the Empire were once more pressing on its narrowed frontiers, he callously ordered117 that the line of signal fires, which were wont to announce the inroad of the enemy from the distant provinces, should be abandoned, so that his chariot races might not be interrupted.

Such was the spectacle which Theodora had to contemplate for ten weary years, nor can she have been unconscious how deeply she was responsible for it. At length, in 866, the infamous career of her brother came to a close, and she was free to return to the Court. A new favourite had arisen and displaced Bardas. A handsome groom in the imperial service, Basil the Macedonian, had caught the fancy of Michael. When Bardas one day denounced a noble for not saluting him in the street, as he passed in the gorgeous robe of a Cæsar—a dignity to which Michael raised him in 865—the noble was deposed from office and Basil put in his place. Basil was married, but the besotted Emperor forced him to divorce his wife and marry Eudocia Ingerina; and, as Michael retained Eudocia as his own mistress, he brought his willing sister Thecla from her nunnery and made her the mistress of Basil. Bardas was now alarmed and perceived that either he or Basil must die. I need not enter into the sordid details. Enough to say that Basil and Michael decoyed the Cæsar from the city, after a solemn oath on the cross and the sacrament, which were held before them by the patriarch, that they had no design on his life, and murdered him. This occurred on Whit-Monday 866; on the following Saturday Basil was crowned and anointed co-Emperor of the Romans.

To this blood-stained and sordid Court Theodora did not hesitate to return as soon as Bardas was slain. One of the chroniclers tells an anecdote which would, if one dare reproduce it in full, give some idea of the atmosphere which she breathed. Michael one day summoned her to come and receive the blessing of the patriarch, who was with him. She entered and bent in inobservant reverence before the vested figure beside her son, and she was, to the loud delight of Michael, startled by an outrage that the rudest peasant would hardly suffer to be offered to his mother. It was the infamous mock-patriarch Gryllus, perpetrating his coarsest joke.

This, however, seems to have occurred before her abdication, and she seems, after the murder of Bardas, to have lived chiefly in the Anthemian palace across the water. Unfortunately, the last scene in the squalid reign of her son shows that she still tolerated his excesses. Basil, in turn, had seen a new favourite arise and threaten his hope of inheriting the Empire. In a drunken fit Michael had put his purple slippers on a vulgar servant—a man who had formerly rowed in the galleys—for praising his chariot-driving, and brutally observed to the tearful Eudocia, who sat beside him, that the man was more fit for the purple than her husband. Basil, if not Eudocia, concluded that the Emperor must be assassinated, and before long Theodora provided them with an opportunity. I am not for a moment suggesting that Theodora was aware of their intention, but this last appearance of hers on the stage of history is a painful close of her career.

She invited Michael to sup and stay at her palace after he had spent a day hunting on the Asiatic side of the water. Such an invitation might be innocent, even virtuous, if there were a design to separate the young Emperor from his associates and, perhaps, endeavour to counsel him. But we find that his usual Court accompanied him, and the evening was spent in drunken debauch. The new favourite, Basilicius, and Michael were put to bed in a drunken condition. Basil, with whom was Eudocia, had slipped from the room and tampered with the fastenings of their doors, and in the middle of the night Theodora awoke to hear the clash of swords and cries of hurrying men; Michael and Basilicius had been murdered, and Basil and Eudocia were hastening to Constantinople to secure the palace.

The last glimpse we have of St Theodora is when she and her daughters convey the remains of the wretched119 Emperor to the city for interment in the great marble tombs of the kings. It was the autumn of 866, and, as the Greek Church celebrates her festival on 11th February, we may assume that she lived a few months afterwards in sad, if not penitent, obscurity. Few in modern times, even of those who share her creed, would venture to describe her as “the glory and ornament of her sex.” No woman of high character could have been betrayed into the criminal blunders which Theodora committed, however exalted she may have considered her ultimate aim to be. Yet we may grant that she was rather tainted by the pitiful casuistry of her time than evil in disposition, and the historical memorial of her life-work is a sufficiently terrible punishment of her errors.

It remains briefly to dismiss the Empresses Eudocia and Thecla. On the morning after the murder Eudocia Ingerina sat proudly by the side of her husband, in the glorious robes and jewels of a reigning Empress, as he went to the great church to consecrate his Empire to Christ. She enjoyed her dignity for about fifteen years, but the only incident recorded of her is that she was detected by her husband in a liaison with a steward of the table. Thecla was discarded at the death of her brother and passed to less exalted lovers. Some years after his accession she sent a servant with a petition to Basil. “Who lives with your mistress at present?” the Emperor cynically asked. “Neatocomites,” the man promptly replied. Neatocomites was flogged and put in a monastery, and Thecla was flogged and robbed of the greater part of her fortune. It is the last glimpse we have of the family of St Theodora.

t

t

click here for icons of christ

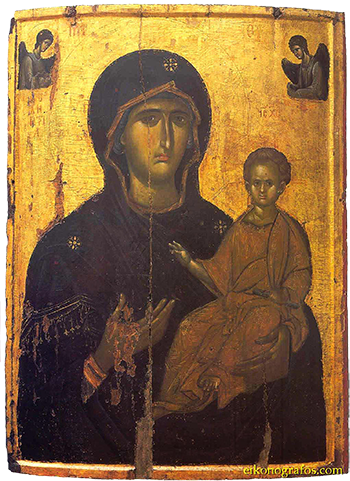

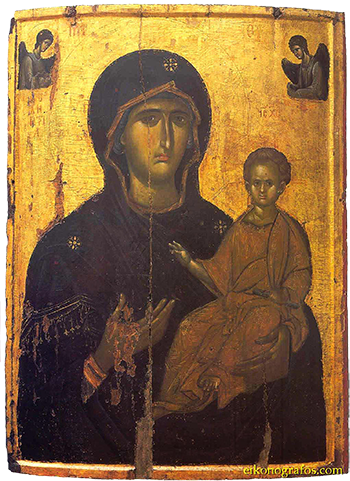

click here for icons of christ click here for icons of the theotokos

click here for icons of the theotokos click here for icons of angels

click here for icons of angels click here for icons of saints

click here for icons of saints