t

t

12th century Constantinople must have had 10,000 icon painters competing for business. Although we can assume that there were lots of freelance artists, most painters would have been part of a workshop or attached to a monastery. Icons, both new and antique, were sold in shops, from street kiosks, and even by street peddlers. There must have been a staggering range in artistic quality when so many painters are involved. Among potential patrons of icon painters the Imperial Court and the Patriarchal church would have been the most important. Every workshop and painter would have aspired to to work for them. Being an officially recognized painter could give an artist a level of protection, but you were only as good as your last icon. This is the eternal struggle of all artists - you can be famous one day and forgotten the next. No matter how good you think you are there is always someone better and cheaper competing for business.

Icons could be created in cheaper materials to reduce their cost. Gold backgrounds, which were usually tooled gesso like leather, could be substituted with cheap silver leaf, which was then glazed in orange colored shellac to imitated gold. Icons could be painted on flat wood backgrounds instead of panels with hollowed-out centers. Panels could be painted on cheaper woods (resulting in splits), be made of smaller pieces of wood glued together, or just made much thinner to save money on them. Painters could use cheaper pigments, too. One can assume that many Byzantine icons made for the mass market where produced in assembly line fashion, with one artist painting faces, another clothes and another doing backgrounds. Styles - even in icon painting - changed rapidly. Subject matter changed as well, pilgrims wanted icons of their own national saints, like Boris and Gleb for the Russians. The peddlers of icons who trolled the streets would also besiege potential customers inside and outside places like Hagia Sophia. The gates of Hagia Sophia were the number one spot for painters to sell their wares on the streets.

Icons could be created in cheaper materials to reduce their cost. Gold backgrounds, which were usually tooled gesso like leather, could be substituted with cheap silver leaf, which was then glazed in orange colored shellac to imitated gold. Icons could be painted on flat wood backgrounds instead of panels with hollowed-out centers. Panels could be painted on cheaper woods (resulting in splits), be made of smaller pieces of wood glued together, or just made much thinner to save money on them. Painters could use cheaper pigments, too. One can assume that many Byzantine icons made for the mass market where produced in assembly line fashion, with one artist painting faces, another clothes and another doing backgrounds. Styles - even in icon painting - changed rapidly. Subject matter changed as well, pilgrims wanted icons of their own national saints, like Boris and Gleb for the Russians. The peddlers of icons who trolled the streets would also besiege potential customers inside and outside places like Hagia Sophia. The gates of Hagia Sophia were the number one spot for painters to sell their wares on the streets.

Painters also sold their works through retail stores were you could pick from hundreds of icons of almost every saint. If you didn't see that you wanted it would have been easy to order an icon and have it in a few days. These stores and workshops could also send icons via land and sea to your home - even in Russia and Spain. You would even special order complete set of icons for you church and have them delivered when they were completed.

Painters also sold their works through retail stores were you could pick from hundreds of icons of almost every saint. If you didn't see that you wanted it would have been easy to order an icon and have it in a few days. These stores and workshops could also send icons via land and sea to your home - even in Russia and Spain. You would even special order complete set of icons for you church and have them delivered when they were completed.

In 1274 a complete cargo of the best icons - maybe two hundred or more - was lost on its way to the Council of Lyons in France from Constantinople - wrecked at sea off the coast of the Morea, it was part of a two ship caravan taking participants to the council. The second ship survived. The icons were meant as gifts and to be used in Orthodox church services in France.

in 1280 Emperor Michael VIII Paleologos sent Peter, the king of Aragon, a shipment of gifts including large icons of the finest quality and other artistic treasures from Constantinople. It is possible the Kahn and Mellon Madonnas were part of this shipment.

Packing icons was an art in and of itself, they came with cloth covers and wooden crates. Special work was required to protect the fragile layers of gold that have been laid on in the background of an icon and also used to highlight robes and clothing. Wood was very inexpensive in Constantinople and carpenters were skilled in their trade both is making the boards for icons and also protecting them with boxes and crates.

Men and women worked together in these family dominated stores that could have 20 or more employees of all ages. Training of new artists took place right there in the workshop. Boys followed their fathers into the profession of icon painting. These workshop-stores were open to the street and had counters were men and women sold their wares. Both sexes where involved in the production of icons, with men being the primary workers an painters. Women often did the final finishing of fine gold decoration by hand with exceedingly fine brushes dipped in honey with loose gold blown across the surface of the icon.

Breaks and meals were taken onsite or in the hundreds of taverns and restaurants in the city. Food and wine was cheap and plentiful. People ate lots of fish and bread and drank gallons of beer. There were lots of street vendors who delivered food and drink right to your home or place of work. I imagine artists and workshop employees socialized together in taverns sharing ideas and business stories of their clients.

Breaks and meals were taken onsite or in the hundreds of taverns and restaurants in the city. Food and wine was cheap and plentiful. People ate lots of fish and bread and drank gallons of beer. There were lots of street vendors who delivered food and drink right to your home or place of work. I imagine artists and workshop employees socialized together in taverns sharing ideas and business stories of their clients.

Constantinople had taverns which catered from the lowest to the richest clienteles. Trade and public associations often hosted banquets in taverns or in public spaces during festivals.

Huge tables covered with food and drink were laid out in front of Hagia Sophia for special events. Free food was also distributed to the poor in the courtyard of the church.

Most artists bought their brushes, paints and other art supplies in shops or from street vendors. Lapis lazuli paint had to be purchased from special stores by weight and was not widely used for blue hues. Lapis is very hard to work into paint. It has to be grinded very finely and it takes much effort to wet the pigment so it can be used. Lapis comes in a number of grades for blueness. Cheaper lapis pigment has more gray in it. Ochre colors in hues of red, gold and brown were cheap and easy to use. One beautiful bright blue color, azurite, was made of blue ground glass. Green malachite was an expensive green hue. Purple robes were painted in red-brown ochre. Pigments were sold dry and in glass, pottery or even cloth-bag containers. Paintings were finally varnished in oil.

Most artists bought their brushes, paints and other art supplies in shops or from street vendors. Lapis lazuli paint had to be purchased from special stores by weight and was not widely used for blue hues. Lapis is very hard to work into paint. It has to be grinded very finely and it takes much effort to wet the pigment so it can be used. Lapis comes in a number of grades for blueness. Cheaper lapis pigment has more gray in it. Ochre colors in hues of red, gold and brown were cheap and easy to use. One beautiful bright blue color, azurite, was made of blue ground glass. Green malachite was an expensive green hue. Purple robes were painted in red-brown ochre. Pigments were sold dry and in glass, pottery or even cloth-bag containers. Paintings were finally varnished in oil.

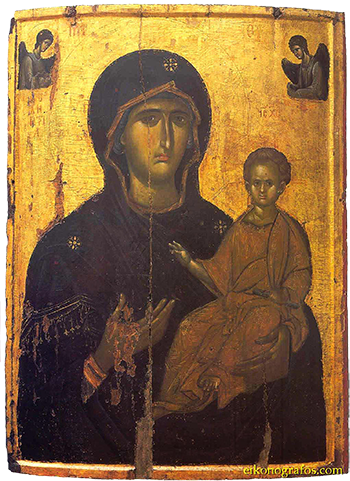

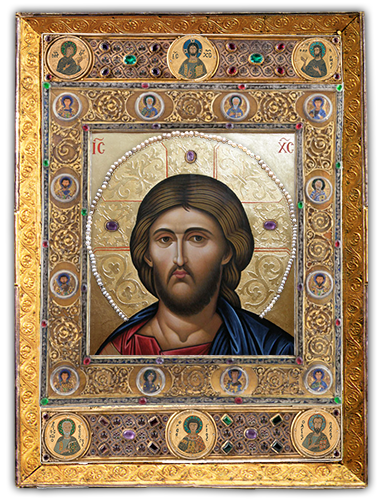

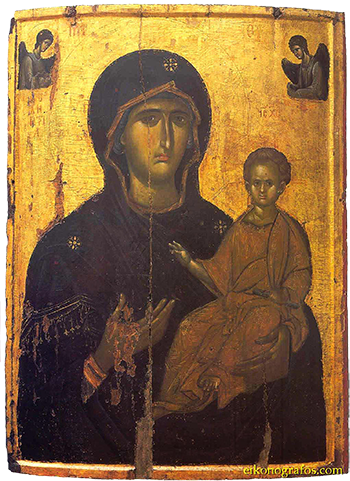

Icons were not expensive being the same cost as a clay or metal kitchen pot. Every orthodox family could have owned dozens of them in all sizes and subject matters. Everyone would have had an icon of Christ and another of the Theotokos. Icons were hung in the corner of rooms and were lit with special oil lamps.

Hardstone agate and wolf's teeth were used to burnish the gold. Burnishers were very valuable and were passed on from generation to generation of artists.

People often slept in their workshops of had lodgings nearby. Artists lived alongside the general public in multi-storied buildings. Everyone were renters, except for rich building owners and monasteries.

The streets were dark, narrow and dangerous. Pick-pockets were everywhere. Fires were frequent. The city was huge with more than 500,000 inhabitants in the 12th century. Like all great cities Constantinople had its own unique smell that visitors remarked on. It was a smell of street food, tanneries and sewage.

Fortunately for the 12th through the 15th centuries Byzantine icon painter had were lots of of potential individual patrons with money. Many of them would have been people who knew artistic quality and fine technique when they saw it and would buy it when they found it.

Fortunately for the 12th through the 15th centuries Byzantine icon painter had were lots of of potential individual patrons with money. Many of them would have been people who knew artistic quality and fine technique when they saw it and would buy it when they found it.

Below the Imperial court and the Patriarchate there were also wealthy nobles and rich monasteries who were knowledgeable patrons of art. There was also a business in the repair and restoration of old icons.

There were many portrait painters in the city, one named Andreas became famous enough that a historian recorded his name. His dad was a cleric in Hagia Sophia.

In 1204 after the 4th crusade and the burning and looting of the city, most of the painters fled Constantinople as refugees. They ended up in places like the city of Nicaea in Asia Minor. The refugees were stripped of all their valuables before they were allowed to escape the sack. Fortunately brushes and wolf's tooth burnishers would have had no value to the crusaders and icon painters would have been able to escape with the tools of their trade. Colors like the ochres artists used were available in natural sources that were cheap, easy to find and refine for painting. The talent of the icon painters went with them which meant the very best artists arrived in exile and ready to produce wonderful icons in new towns of the finest artistic quality. The only material that might be hard to get was gold-leaf. Icon boards were cheap and easy to produce. The Emperors in Nicaea were eager to show themselves as patrons of Byzantine art and culture so they patronized and supported new workshops of painters who relocated.

When Michael VIII Paleologos took Constantinople in 1261 all of the churches had been wrecked - the Latins had even stripped the lead from the roofs and sold the long timber piers holding them up to shipbuilders. All of the Orthodox icons that could be removed were gone only leaving the art - like wall painting and mosaics - that was fixed to walls.

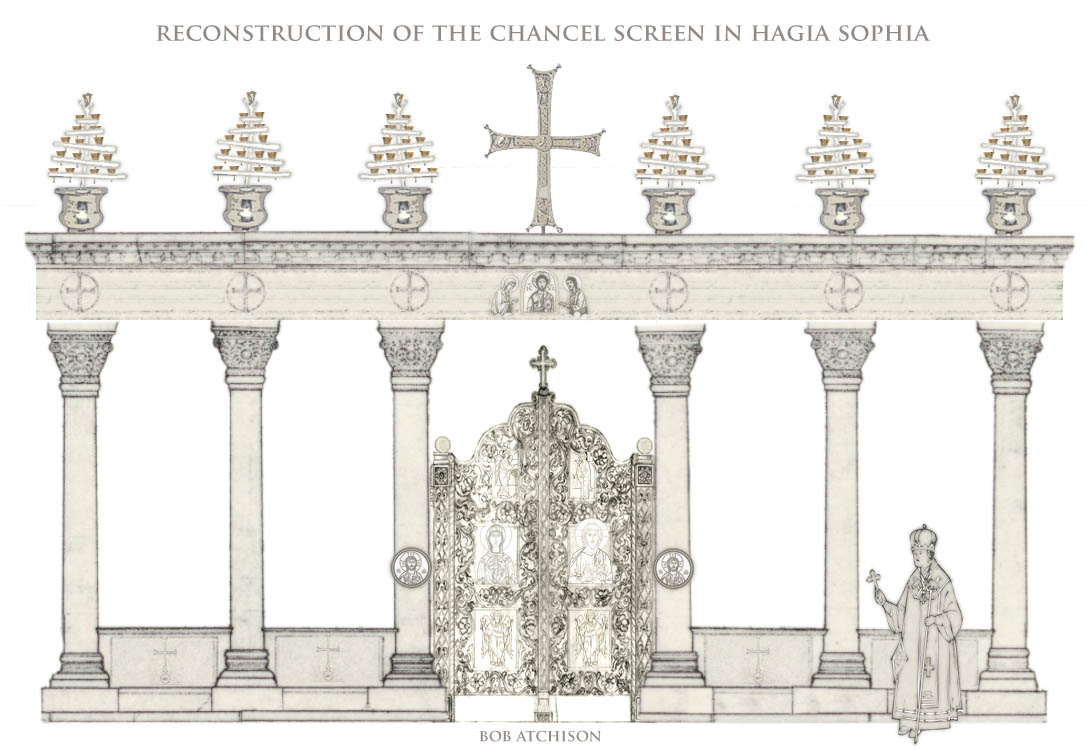

Hagia Sophia was abandoned and empty. There was a huge amount of work to replace everything for Orthodox worship. The iconostasis, altar and ambo had to be rebuilt in stone with huge columns and gilded-wood embellishments and then filled with enormous icons 20 feet tall or more. The icon painters and wood carvers would have been very busy for years not only in the nave but up in the galleries preparing for church councils and Imperial ceremonies. Michael VIII had himself - and his wife - crowned in the nave of Hagia Sophia as soon as the church was ready.

Hagia Sophia was abandoned and empty. There was a huge amount of work to replace everything for Orthodox worship. The iconostasis, altar and ambo had to be rebuilt in stone with huge columns and gilded-wood embellishments and then filled with enormous icons 20 feet tall or more. The icon painters and wood carvers would have been very busy for years not only in the nave but up in the galleries preparing for church councils and Imperial ceremonies. Michael VIII had himself - and his wife - crowned in the nave of Hagia Sophia as soon as the church was ready.

In the last decades of the 13th century peace with Orthodox Serbia meant many artists in Constantinople were invited there to paint churches and icons. These painters had a significant inpact on the cultural life of the new Serbian empire, training local assistants who imported the latest painting styles from Byzantium. There was also a rebirth of the production of luxury goods for the court which needed thrones, crowns, diadems, jewelry and ceremonial robes which were imported from Constantinople.

n 1347 cracks appeared in the eastern vault and arch, but nothing was done and there was a great collapse into the eastern part of the nave and sanctuary. Everything, including the chancel screen, the ambo and the ciborium were destroyed. All of the icons had to be replaced with new ones, another huge project for Constantinople's icon painters and mosaic artists. The structural work looks bad but it has held up ever since. In the dome the Pantokrator mosaic was restored along with the great Seraphim in the eastern pendentives. Also restored were mosaics on the eastern arch, which included new portraits of John V and his wife Anna, John the Baptist, the Mother of God and the Mystical Throne of the Second Coming. The icons of the chancel screen would have been painted wood panels.

n 1347 cracks appeared in the eastern vault and arch, but nothing was done and there was a great collapse into the eastern part of the nave and sanctuary. Everything, including the chancel screen, the ambo and the ciborium were destroyed. All of the icons had to be replaced with new ones, another huge project for Constantinople's icon painters and mosaic artists. The structural work looks bad but it has held up ever since. In the dome the Pantokrator mosaic was restored along with the great Seraphim in the eastern pendentives. Also restored were mosaics on the eastern arch, which included new portraits of John V and his wife Anna, John the Baptist, the Mother of God and the Mystical Throne of the Second Coming. The icons of the chancel screen would have been painted wood panels.

On Tuesday, May 29, 1453 all of the painted icons within easy reach were smashed and destroyed by by Muslims in the conversion of Hagia Sophia into a mosque. All of the icon painters left in the city were either killed or sold into slavery along with the entire population of the city. No one escaped - the 1100 year old Christian civilization was snuffed out in three days.

t

t

click here for icons of christ

click here for icons of christ click here for icons of the theotokos

click here for icons of the theotokos click here for icons of angels

click here for icons of angels click here for icons of saints

click here for icons of saints