From O City of Byzantium by Niketas Choniates

THUS did Emperor Alexios disappear from the world, not yet fifteen years of age. He had reigned for three of these years, but not alone and unaided, for as he was but a child, his mother at first governed the realm, and then the affairs of the empire were administered by two tyrants. It was as though the sun were hidden behind the clouds, and it seemed as though Alexios was subject instead of ruler, commanding and doing whatever the rebels proposed until his life was choked out.

THUS did Emperor Alexios disappear from the world, not yet fifteen years of age. He had reigned for three of these years, but not alone and unaided, for as he was but a child, his mother at first governed the realm, and then the affairs of the empire were administered by two tyrants. It was as though the sun were hidden behind the clouds, and it seemed as though Alexios was subject instead of ruler, commanding and doing whatever the rebels proposed until his life was choked out.

When this loathsome deed had been accomplished, Anna, Emperor Alexios's wife, the daughter of the king of France [Louis VII], was joined in wedded life to Andronikos. And he who stank of the dark ages was not ashamed to lie unlawfully with his nephew's red-checked and tender spouse who had not yet completed her eleventh year, the overripe suitor embracing the unripe maiden, the dotard the damsel with pointed breasts, the shriveled and languid old man the rosy-fingered girl dripping with the dew of love.

Andronikos thereupon requested a second favor of the patriarch who satisfied all his wishes (I speak of Basil Kamateros) and of the synod of that time [c. October 1183]. He asked to be released from the oath which he had sworn to Emperor Manuel and his wretched son, together with all the others who were looked upon as having violated their pledges. The members of the synod, who had received from God the power to bind and loose all sins without discrimination, forthwith published decrees granting amnesty to all those who had breached their oaths. Like an admirer, Andronikos rewarded them for carrying out his orders and readily granted their every request no matter how small or paltry it might be. He paid them the highest honor by sitting in council with them and by having their benches and couches placed close to the imperial throne. Nonetheless, these hierarchs, who were chosen and admitted into his presence, became objects of ridicule, and after a few days of this fantasy of honor and the illusion of glory, Andronikos returned to his former ways like a twig that is forcibly bent, but then springs back to its original position when released. Rather, he deviated even more from his previous behavior; so that he should not appear to be the most unstable of men, suffering from an inconstancy of character even in matters of little consequence, he made it difficult for the hierarchs to gain an audience as he sat on his splendid throne. And they, who but a short while before had been exalted by sitting in the imperial council and had boasted that they had been awarded this high privilege because, in the words of David, they were "the faithful of the land, now withdrew and hid their faces in shame, pitying themselves for having fallen away from God by loosing those things which cannot be loosed and by fawning over Andronikos in vain.

The news of Andronikos's accession and Emperor Alexios's murder reached Alexios Branas and Andronikos Lapardas, the commanders of the divisions which were engaged in resisting, at Nis and Branicevo, Bela, the king of Hungary, who was ravaging the surrounding lands and wreak- ing havoc with the sword. Lapardas despaired for his life and henceforth ever suspected that Andronikos's wide-gaping jaws would one day open and swallow him. Branas, on the other hand, had already declared himself among Andronikos's supporters and welcomed the transfer of imperial power. After giving a great deal of thought to the many ways in which he might escape, Andronikos Lapardas, like a Laconian hound764 in hot pursuit, found one salutary path that would lead him away from the countenance and power of Andronikos, and he would have preserved himself from injury had he persisted in this design and had not ventured on another course of action. With a passionate desire to punish Andronikos and avenge the crime against his lord and emperor, he dared to revolt. He knew that the West would not come over to his side nor be willing to take up and continue the battle against Andronikos because of the presence of his fellow general Branas. Thus he set his eyes on the East, where he was better known because there he had often exercised the highest commands, and that was, moreover, the breeding ground of eager champions of resistance.

After consulting with his fellow commander and persuading Branas to stay at his post, he set out immediately to meet with the aged and newly made emperor, outrunning Rumor, which clearly perceives those things hidden beneath the earth and often sees future events as though they had already taken place. He stayed only a brief time at Orestias, his native city, which others called Adrianople, just long enough to see his sisters there and to make arrangements to go abroad and then hastened his crossing to the East as quickly as possible, for Rumor, the gossipmonger, was already shouting out in the crossroads and broad thoroughfares and from the walls and housetops and in every direction within earshot, he- ralding his flight. One night, therefore, he and his companions came down to the sea, embarked on ships made ready at Hyelokastellion for this purpose and crossed to the other side. After a brief respite here, he hoped to escape utter destruction and being served up as a prepared feast and ready dessert for the waiting jaws of Andronikos. It seems he had been blotted out from the book of the living766 by Providence and was destined to become food for the beast.

Hence, since the Divinity's will was contrary, he was seized and sent to Andronikos by those very men whom he hoped would help preserve him unharmed and enable him to work great and noble deeds, those men in whose might of hand and soul he had trusted to find every kind of support in overthrowing Andronikos. These were figments of a deluded imagination and proved to be dream-like apparitions. At Atramyttion, he was apprehended by a certain Kephalas, a man of great power and the tyrant's most trusted supporter, and he was entrusted into the hands of Andronikos as a sacrificial victim. His eyes were gouged out, and he was cast into the Monastery of Pantepoptes. There Lapardas lamented the

Hence, since the Divinity's will was contrary, he was seized and sent to Andronikos by those very men whom he hoped would help preserve him unharmed and enable him to work great and noble deeds, those men in whose might of hand and soul he had trusted to find every kind of support in overthrowing Andronikos. These were figments of a deluded imagination and proved to be dream-like apparitions. At Atramyttion, he was apprehended by a certain Kephalas, a man of great power and the tyrant's most trusted supporter, and he was entrusted into the hands of Andronikos as a sacrificial victim. His eyes were gouged out, and he was cast into the Monastery of Pantepoptes. There Lapardas lamented the

fact that he had miscalculated the force of the circumstances that opposed him: he had cast the die of rebellion for the best reasons, but Fortune had taken no heed whatsoever of those things which he had undertaken with good counsel and had sided with the worst faction."'

Thus God does not reveal to us whether our lives shall be free from toil and sorrow, neither does he give us any presentment of future evil, or allow us to choose a way of life without danger. This man, who often proved himself a most excellent general, thought it a base act to serve Andronikos after the death of Emperor Alexios. Anticipating that he would be put to death by the tyrant, he chose voluntary exile in the face of certain execution and was taken unawares by him from whom he fled, falling into those hands he sought to escape; supposing that he would take Andronikos from behind in hot pursuit, he was met head-on, engaged face to face, and overpowered.

Not long afterwards, Lapardas departed this life. Andronikos had been so frightened by his defection that all throughout Lapardas's flight he had been haunted by his own imminent destruction; he had feared him be- cause he was sudden and quick to give battle and distinguished by manly courage. In the realization that no headway was being made against him by continued pursuit or by armed combat, the contriver had devised a novel stratagem. He had sent to the governors of the eastern provinces imperial letters whose contents truly spoke in wickedness: Andronikos contended that he had sent Lapardas to Asia and that whatever actions Lapardas should undertake, even though unclear to most in purpose, would be done according to plan and on behalf of his rule, and he urged all to welcome him without hesitation. Andronikos's intent was to thwart thereby the onrush of many who were suspicious as to why Lapardas had resolved to oppose Andronikos and was marching out the ranks of warriors769 as his adversary. Andronikos testified to the rebel's loyalty and commanded that the fugitive be welcomed as though sent by him. But even if these novel letters effectively achieved their purpose, it was im- possible to foresee how quickly the man would be taken.

Not long afterwards, Lapardas departed this life. Andronikos had been so frightened by his defection that all throughout Lapardas's flight he had been haunted by his own imminent destruction; he had feared him be- cause he was sudden and quick to give battle and distinguished by manly courage. In the realization that no headway was being made against him by continued pursuit or by armed combat, the contriver had devised a novel stratagem. He had sent to the governors of the eastern provinces imperial letters whose contents truly spoke in wickedness: Andronikos contended that he had sent Lapardas to Asia and that whatever actions Lapardas should undertake, even though unclear to most in purpose, would be done according to plan and on behalf of his rule, and he urged all to welcome him without hesitation. Andronikos's intent was to thwart thereby the onrush of many who were suspicious as to why Lapardas had resolved to oppose Andronikos and was marching out the ranks of warriors769 as his adversary. Andronikos testified to the rebel's loyalty and commanded that the fugitive be welcomed as though sent by him. But even if these novel letters effectively achieved their purpose, it was im- possible to foresee how quickly the man would be taken.

Having repulsed this terror beyond all expectations [before Christmas 1183], the emperor's niggardly soul was gladdened even as the corn with dew upon the ears.' He set out from the City and, making his way leisurely with brief stopovers, came to Kypsella."' After enjoying himself in the chase in those parts, he arrived at the monastery founded by his father in Vera and visited his father's tomb, escorted by his bodyguard and in the full imperial splendor which his father had long ago desired but never attained; it was from his father that Andronikos inherited his passion to become emperor. During this period, which many called the halcyon days, he desisted from inflicting injury and returned shortly to the imperial palace, as the Feast of the Nativity was at hand.

With the coming of spring [1184] he attended the horse races and spectacles and then assembled all the troops, those from the western and eastern armies who had not rebelled, and took the road leading directly to the city of Nicaea. He dispatched Alexios Branas, who had returned from the regions of Branicevo, with a large force to be drawn out in battle array around Lopadion. The Lopadians had already joined their neighbors, the Nicaeans and the Prusaeans, in revolt. Since the expedition fared well for Branas and he had brought a successful conclusion to the campaign, he continued on to Nicaea, where he joined forces with Andronikos. When both armies were gathered together into one force, Andronikos determined to assault the city. The defenders were insolent, not only when Andronikos was absent, but they also scorned him when he was present; appearing on the wall, they defended themselves with weapons and delivered blows of vulgarities, sparing neither missile nor obscenity. The gates of the city were shut and securely bolted, but the gates of the lips opened wide, and the defenders' tongues issued forth from the breastworks of the teeth to discharge missiles of scurrilities against Andronikos. Cut to the quick by such darts, he breathed forth a fire of wrath,"` forcing out a Typhonian blast, and was unable to contain his resentment, for the city of Nicaea boasted to be impregnable, or very nearly so, thanks to her mighty walls built all of baked bricks. At that time, soldiers who abhorred Andronikos streamed into the city. Among these were Isaakios Angelos, who later put an end to Andronikos's tyranny and held sway over the Romans after him, and Theodore Kantakouzenos, as well as Turks who were invited inside, all of which seemed to him to bode no good for the besiegers.

With the coming of spring [1184] he attended the horse races and spectacles and then assembled all the troops, those from the western and eastern armies who had not rebelled, and took the road leading directly to the city of Nicaea. He dispatched Alexios Branas, who had returned from the regions of Branicevo, with a large force to be drawn out in battle array around Lopadion. The Lopadians had already joined their neighbors, the Nicaeans and the Prusaeans, in revolt. Since the expedition fared well for Branas and he had brought a successful conclusion to the campaign, he continued on to Nicaea, where he joined forces with Andronikos. When both armies were gathered together into one force, Andronikos determined to assault the city. The defenders were insolent, not only when Andronikos was absent, but they also scorned him when he was present; appearing on the wall, they defended themselves with weapons and delivered blows of vulgarities, sparing neither missile nor obscenity. The gates of the city were shut and securely bolted, but the gates of the lips opened wide, and the defenders' tongues issued forth from the breastworks of the teeth to discharge missiles of scurrilities against Andronikos. Cut to the quick by such darts, he breathed forth a fire of wrath,"` forcing out a Typhonian blast, and was unable to contain his resentment, for the city of Nicaea boasted to be impregnable, or very nearly so, thanks to her mighty walls built all of baked bricks. At that time, soldiers who abhorred Andronikos streamed into the city. Among these were Isaakios Angelos, who later put an end to Andronikos's tyranny and held sway over the Romans after him, and Theodore Kantakouzenos, as well as Turks who were invited inside, all of which seemed to him to bode no good for the besiegers.

For many days, Andronikos rode up to the walls but was unable to accomplish anything; it seemed to him that he was assaulting precipitous mountains, or that he was foolishly engaging stony ridges in battle and contending against Arbela"s and the walls of Semiramis, or shooting arrows into the sky. The defenders fought furiously: with weapons they beat back the assaults made by weapons; and with their war engines they rendered totally useless the stone-throwing machines contrived by the ingenious Andronikos, who set up a battery of wall-demolishing siege engines and employed miners, making use of everything possible to bring down the city's walls. Emulously vying with those present, Andronikos boasted that he was supremely skilled in the art of taking cities. On the one hand, he positioned the siege engines, carefully examined the sling, secured both the withy end and the crank handle, and reinforced the battering ram with iron; the defenders, on the other hand, leapt forth from the city's hidden posterns, put the torch to the war engines, and smashed them by hand; when similar engines were moved up to the walls, they demolished them like the threads of a spider's web.75 When Andro- nikos saw all his deliberations brought to naught, he contrived an inhu- man deed which had been executed a few times in the past by both besiegers and besieged.

Euphrosyne [Kastamonitissa], the mother of Isaakios Angelos, was brought from Byzantion. Andronikos proposed at first to use her as a shield for the siege engines, but instead he placed her on top of the battering ram as though it were a carriage and moved the engines of war up to the walls. One could not but both weep and marvel at such a spectacle-weep because this strange sight was the cause of fury compounded by the fact that the perpetrators shrank not from an act so incredible and alien to human nature-and marvel that the frail woman, seated on top of the engines of war and hauled to the city's walls, had not died of fright. For the first time, mortals were to see soft feminine flesh become a bulwark for iron, exchanging its function for a dissimilar one,

the fragile human frame projecting out from the hard engines of war to prevent metal from smashing against metal, the human body giving cover to iron. The defenders discharged their missiles from the walls as before, but with great care, so as to wound and strike down the attackers while preserving the noblewoman from all bodily harm; it was as though by gesturing with her hands and nodding, she deflected the missiles away from herself and transfixed them in the hearts of the enemy. Then did Andronikos perceive that this inhuman contrivance would accomplish nothing. As for the Nicaeans, sallying forth at night, they set fire to the engines of war and pulled the woman up by a rope, or like Harpies snatched her up and carried her off, leaving Andronikos behind beating his breast like another Phineus with no meat to set before the hungry beast of his anger. Thus the Nicaeans, who knew great glory for their bravery against the enemy, displayed yet more manliness, and they prosecuted the war with increased vigor and courage.

They appeared on the walls and performed noble deeds and poured down abuse on Andronikos, calling him butcher, bloodthirsty dog, rotten old man, undying evil, Avenger of men, lover of women, Priapos,"' and more aged than Tithonos and Kronos, and every other obscene thing and name. According to reports, they leaped down from the battlements and poured out of the gates. Andronikos, with ashen face and unnatural scowl, twisted his flowing, curly beard with his finger as though he were plying the loom and made no secret of his anger as he wove cunning wiles against the Nicaeans.

Hungering like a dog, which has nothing to feed on, in the words of David,"' he would go round about the city, and, like a bear at a loss marching forth,7' he berated the regiments and castigated the commanders for being inept in warfare and avoiding battle.

Theodore Kantakouzenos, a bold man and in the prime of his life, like newly treaded wine fermenting in the wine vat, observed Emperor An- dronikos one day as he was making a circuit of the city with a sizeable contingent of troops and cavalry regiments. Motivated by a sudden impulse, he leaped forth through the open eastern gates, followed by a few other horsemen, and tilted his lance against Andronikos as he rode out in front. Charging at an ever-quickening pace, he dug his spurs into his horse, urging it to fly as though nature had furnished its feet with wings, but he missed his mark and destroyed himself. When the horse tripped over a hole and fell on its knees, Kantakouzenos was thrown from his saddle: the front of his head struck the ground as he fell head over heels, his back muscles suffered serious injury, and he lay in a daze with his strength spent. Thereupon, many of Andronikos's troops rushed forward with swords drawn and decapitated him; others severed his body piecemeal according to Andronikos's wishes. Shortly afterwards, Kantakouzenos's head, raised on a pike, was exhibited to the inhabitants of Constantinople and paraded through the streets of the City.

The Nicaeans, deprived of their daring and invincible champion, mourned the fallen man greatly and lost heart. They looked to Isaakios Angelos and wished to submit to him and to have him serve as their leader. But he was irresolute and, like Aeneas, stood aloof from the contest,"" looking into the future and imagining that the emperorship was reserved for him to the glory of his family, for he did not highly regard the sovereign.

The Nicaeans, deprived of their daring and invincible champion, mourned the fallen man greatly and lost heart. They looked to Isaakios Angelos and wished to submit to him and to have him serve as their leader. But he was irresolute and, like Aeneas, stood aloof from the contest,"" looking into the future and imagining that the emperorship was reserved for him to the glory of his family, for he did not highly regard the sovereign.

He entered into negotiations with the Romans, and, as a result, the zeal of the troops gradually diminished, and their noble and inspired elan was snuffed out. They met together and in tragic terms declaimed of the terrible hardships the besieged must endure as though these were taking place before their very eyes. Reflecting on Andronikos's cruelty, they considered the diverse kinds of torture and suffering that prevail according to the law of warfare whenever a city is taken by force, and they cowered like leverets; as Kaineus, according to myth, was changed from a woman into a man, they, on the other hand, succumbed to womanish softness, and none cherished the idea of performing deeds of virtue. It was as though with Kantakouzenos's death they had all perished with him and their daring and ardor for warfare lay buried.

Nicholas, the archbishop of Nicaea, realized the grim realities of the situation and argued for the necessity to be generous. Summoning the people to the church, he proposed that they yield to the times and circumstances. Ere the city was deluged by the waves of battle, they would do best voluntarily to hand it over to Andronikos, as it was evident that Andronikos, who had nothing to distract or divert his attention elsewhere, would never return empty-handed and that the Nicaeans were little by little abandoning the watch and ward of the city and inclining towards the cause of peace. Everyone considered the archbishop's suggestion an excellent one, and he grasped the ensuing good with both hands. Donning his sacred vestments and taking into his hands the Holy Scriptures, he commanded the church attendants and all of the remaining citizens to follow him so that neither women nor children would be missing from the procession. They were to bear no weapons and to wave olive branches as suppliants,"' with head and hands uncovered and feet bare, presenting themselves as true suppliants and exciting pity with their ges- tures of wretchedness and their submissive cries.

In such manner did they pour forth from the city. Emperor Andronikos, taken by complete surprise by this unexpected spectacle, blinked many times to verify the reality of what he beheld; he thought that all that he saw was but a dream. Once assured that his eyes were not playing tricks on him, he put aside all sentiments of noble-mindedness and sincerity befitting an emperor, and the deranged man perverted mercy; having no lion skin to put forth, he donned the fox skin,' pretending to receive them gladly and nearly shedding tears. This was an old trick of Andronikos to conceal the truth.

But he did not play the role for long. Soon he cast off his soft words, smoother than olive oil, like so many rags and openly demonstrated to the Nicaeans and, in particular, to those who excelled in rank and nobility of birth how great was the wrath nurtured by the old man. and how, as his rancor, hatred, and malice smoldered, he was in time to dispense retribution. Many were forced to become fugitives from their homeland, while others, cast headlong from the walls, suffered a most horrible death. As for the Turks, he impaled them in a circle around the city.

He extolled Isaakios Angelos for his words and deeds, for Isaakios did not make use of his teeth as weapons and missiles as Theodore Kantakouzenos had done; instead, he had rebuked the latter many times for speaking insolently against the anointed of the Lord and for unsheathing the tongue from his mouth like a sharp sword. Andronikos filled Isaakios with great expectations, thus nurturing by divine direction his own murderer, the man who was to remove him from the throne and whom he cherished for as long as Providence decreed, and he sent him back to Byzantion while he marched on to the city of Prusa with his troops.

He began the siege immediately and established an entrenched camp south of the city, where it appeared that the wall was approachable because here the terrain was level, whereas the rest of the city was situated high on a rocky and rounded hill which jutted out precipitously. The engines of war and the men did not remain idle but performed their tasks suitably. Andronikos, who was given to loquaciousness, attached winged words to the volant shafts of missiles and shot these into the city. These letters borne through the air offered encouragement for a change, and amnesty for evils, should they open the gates, welcome him inside, and seize Theodore Angelos and Lachanas of the marketplace790 and the wit- less Synesios, to use Andronikos's words, as well as their partisans, and give them up. He repeated this for a considerable number of days. Nor was the battle waged against Prusa inferior to that joined against Nicaea in regard to both the prowess of those men who engaged the imperial divisions and the hatred that was felt for Andronikos, the cause of hostilities. Prusa was a city of beautiful towers, encompassed by formidable walls which were double in the southern region. When the two armies joined in battle there were many sallies and many fell on both sides.

As it was fated that this city should bow under the yoke of Andronikos and that the majority of the inhabitants be taken captive and suffer utter ruin, a portion of the wall, repeatedly struck by the siege engines, crumbled. Moreover, when the addition to the old wall at this spot and the girt timbers were thrown down, it appeared to those within that the entire section of the wall struck by the siege engines had come tumbling down, and an unintelligible cry rose up and terror gripped the hearts of all. Frightened almost to death by the crashing noise of the dislodged stones, the defenders abandoned their posts without ascertaining the extent of the damage, descended from the walls, and collected in the streets in a state of confusion. As a result, the enemy easily gained entry into the city through the gates and by way of the scaling ladders placed against the walls. The Prusaeans were seized and cruelly killed; their possessions were carried away as plunder, and the fatted beasts, the flocks of sheep, and the herds of cattle which had been driven into the city to feed the inhabitants during the siege were slaughtered. Such were the horrors inflicted at that time.

Afterwards, Andronikos entered the city and lodged within, but he did not conduct himself as a meek emperor and savior before the Prusaeans, who were former and future subjects even though they had rebelled for a time, but like a ravenous lion falling on unpenned and shepherdless flocks, he broke the neck of one, devoured the inward parts of another, and did even worse things to a third; the rest he scattered in the direction of cliffs and mountains and chasms. In this fashion did Andronikos behave. Since there had been no preceding formal compact or truce with the citizenry of Prusa, nor had a voluntary surrender been negotiated, and as the city had been taken by force, he utterly ruined and destroyed the vast majority, portioning out his savage anger in manifold and diverse punishments.

He had Theodore Angelos, an unmarried youth with the first down of hair on his cheeks, blinded, placed on an ass, and led away beyond the Roman border and gave instructions that he be then released so that he should roam alone wherever the beast of burden should take him. And Angelos would surely have become food for beasts,'94 which was what Andronikos intended when he inflicted this punishment on him, had not the Turks met up with him, taken pity on the youth, and, leading him to their tents, tended his wounds. Leon Synesios and Manuel Lachanas, as well as forty others, he hanged on the branches of trees growing alongside Prusa. He inflicted punishments on many more: the hands of some he cut off and clipped their fingers as though they were branches of grapevines, and he severed the legs of others. Many were deprived of both hands and eyes; some lost their right eye and left leg and again others suffered the reverse.

Having thus brutally deprived his own reign of those who excelled in bodily strength and miltary experience, Andronikos departed for Lopadion where he perpetrated the same crimes. He deprived the bishop of one of his eyes because he showed no indignation against the seditionists, having submitted meekly and calmly to their movement against Androni- kos and stood by without bringing charges, and he returned to the palace delighting in such trophies, leaving behind the cultivated vines of the Prusaeans that climbed trees in close embrace weighted down with the bodies of the hanged like so many clusters of grapes. He allowed none of the impaled to be buried; baked by the sun, they swayed in the wind like scarecrows suspended in a garden of cucumbers by the garden-watchers.

Returning to the City to the acclamations of the populace and the adulation of flatterers, whom the palace ever maintains, he became even more arrogant. In the summertime [1184], when he turned his attention to spectacles and horse racing, a section of the railing of the imperial box collapsed, killing about six men. The fanatic Hippodrome mob became agitated by what happened, and Andronikos, pale with fear, gathered together his bodyguards and jumped from his seat to beat a retreat to the palace, but his favorites pleaded with him to set aside this unseemly resolve and convinced him to remain firmly seated for the time being. They feared he would perish should he rise up and depart, for the fac- tions would then join forces and attack him and his supporters. He remained there only a short while, until the horse races and gymnastic games were concluded, and removed himself completely from the subsequent spectacles in which those who clamber up ropes with hands and feet and dance high in the air on small and delicate tightropes amuse the spectators; moreover, the wing-footed hares and the hunting hounds demonstrated how fond of such novel sights were those who frequented the amphitheater. In this wise then did these events take their course.

There was a certain man named Isaakios (not Isaakios Angelos) of noblest birth, the son of the daughter of Isaakios the sebastokrator, who, as our history has recorded, was Emperor Manuel's brother. This Isaakios, appointed by his granduncle Emperor Manuel, governor of Armenia and Tarsus and general of the troops stationed in these parts, met the Armenians as adversaries in battle and was taken captive. He was incarcerated in a fortress for many years, during which time Emperor Manuel died. Later ransomed by the Hierosolymitai, who are called friars, he deemed it fitting to return to his homeland to enlist Andronikos's help in repaying the ransom money on the advice of Theodora, with whom, as we have often said, Andronikos had sexual relations; this Isaakios was her nephew. Constantine Makrodoukas, the husband of Isaakios's mater- nal aunt, and Andronikos Doukas, Isaakios's kinsman and fast friend from childhood, urged Andronikos to receive Isaakios favorably and to pity him his lengthy exile.

But this Isaakios, who imagined his homeland to be as distant as the stars, did not wish to submit to Emperor Andronikos, and he paid no heed to the advice of kinsmen or cherished companions of his youth. Aspiring to power, he passionately desired to become emperor himself, and unable to bow to the yoke of rulers, he ill-advisedly used the monies, provisions, and auxiliary forces sent him from Byzantion to canvass for the throne. Therefore, with a large force he sailed down to Cyprus, where he first represented himself as the lawful ruler commissioned by the emperor [c. 1183]. Producing for the Cypriots imperial letters which he himself had composed, he read aloud counterfeit imperial decrees osten- sibly representing his responsibilities and did those other things which those who are deputed by others to govern are required to do. Not long afterwards, he exposed himself as a tyrant, revealing the cruelty which he nurtured and behaving savagely towards the inhabitants.

Such was the disposition of this Isaakios that he so far exceeded Andronikos in obdurateness and implacability as the latter diametrically surpassed those who were notorious as the most ruthless men who ever lived. Once he felt secure in his rule, he did not cease from perpetrating countless wicked deeds against the inhabitants of the island. He defiled himself by committing unjustifiable murders by the hour and became the maimer of human bodies, inflicting, like some instrument of disaster, penalties and punishments that led to death. The hideous and accursed lecher illicitly defiled marriage beds and despoiled virgins. He irresponsibly robbed once prosperous households of all their belongings, and those indigenous inhabitants who but yesterday and the day before were admired and rivaled Job in riches, he drove to beggary with famine and nakedness, as many, that is, whom the hot-tempered wretch did not cut down with the sword.

Alas and alack, how the ways of ungodly men prosper! They flourish who deal treacherously. Thou hast planted them, and they have taken root; they have begotten children, and become fruitful. Thus did the prophet make his defense to the Lord when speaking of judgments. For that generation, one might say, produced hemlock to ripen for no other purpose than to bring death to those to whom it was offered, and utter ruin to the majority of cities whose government they 'lawlessly seized.

When Emperor Andronikos heard of these events, in no way whatever could he be restrained, for he saw that which of old had terrified him now about to befall him (he suspected that the letter iota would put an end to his rule).800 He sought some means by which Isaakios might be apprehended and his anticipated destroyer sent from this life; he was afraid lest Isaakios sail from Cyprus and overthrow his tyrannical rule, knowing full well that Isaakios would be warmly received by all, since the evil from afar seems less grievous than that which is at hand, and the greater evil which awaits us appears less oppressive than that which afflicts us in the present. It seems to be a human trait to be content with any brief and incidental relief from suffering.

But he had no means with which to subdue the absent enemy, and thus he turned his anger against those at hand, doing the same thing that dogs are often wont to do: retreating before anyone who throws a stone at them, they defend themselves by barking, but once the stone is thrown, they attack with snapping teeth. Indeed, he put on trial Isaakios's uncle, Constantine Makrodoukas, and Andronikos Doukas, who made a pledge of good faith before Andronikos that they did not wish to see the worthless Isaakios set loose and returned to his homeland. A few days later, they were charged with the crime of lese majesty, despite the fact that they were the most eminent leaders of Andronikos's party and the most powerful members of his faction.80' On the one hand, there was Makrodoukas, who, besides the various proofs of friendship he had diligently bestowed on Andronikos, was also married to the sister of Theodora with whom, as has been often recorded, Andronikos had illicit relations; Andronikos Doukas, on the other hand, was a lecher and a knave, with shamelessness written on his face, who pretended to be the staunchest supporter of Andronikos's cause. Whenever Andronikos resolved to gouge out the eyes of someone, Andronikos Doukas, an apt pupil of the murderer who from the beginning802 delights in the ruin of human beings, would also decree the loss of hands or decide on impalement, frequently uttering imprecations against Andronikos and upbraiding him most shamelessly for not inflicting suitable punishments for offences committed.

When the most splendid and auspicious day arrived on which the bodily ascension of our Lord and Savior into the heavens is celebrated [21 May 1184], all the attendants of the imperial court were summoned to assembly; consequently, there was a tumultuous concourse and sudden rush of representatives of every race and nation to the place where the emperor was sojourning. At that time he had taken up quarters at the Outer Philopation, as it was called. It was as if those who were gathering were singing a palinode, and as they came running, they took another route that led to the so-called palaces of Manganes, which were also built inside the Philopation and were later razed by Andronikos. When large,. extremely large, crowds had swelled the gathering, and no one was missing whose presence was required, Doukas and Makrodoukas suddenly were ushered from the nearby ground-floor prisons and paraded before the court and assembled throng as condemned criminals. Led forth as under judgment, they saw the emperor leaning out from the upper chambers, and they played their role by raising their eyes and solemnly cross- ing their hands. Stephanos Hagiochristophorites, called Antichristoph- orites803 by the people of that time who converted his name according to his works (for he was in fact the most shameless of Andronikos's attendants, filled with every wickedness),804 picked up a stone the size of his hand, took aim, and threw it at Makrodoukas, the most excellent of the emperor's in-laws, the most venerable in age, and by far the richest. He urged everyone to follow his example, and looking round at the entire assembly, he badgered anyone who did not cast a stone and vilified him as being disloyal to the emperor and threatened that he would shortly suffer the same sentence.

Intimidated by this threat, the entire assembly picked up large stones and hurled them at the men; the spectacle that followed this mischief was piteous and incredible, and the stones rose up into a heap. As the men were still breathing, certain attendants who were assigned this task lifted them up and wrapped them in the blankets which cover the pack saddles of mules. They carried Doukas to the opposite shore which had been set aside for the burial of the Jews, while they brought Makrodoukas to a hilly promontory on the side of the straits opposite the Monastery of Mangana, and both men were impaled.

For the first time the Constantinopolitans saw with their eyes what they could not believe with their ears; heretofore when such things had been related to them, they would stop up the orifices of the ear, but now that these things were taking place before their very eyes, they wailed aloud. And as they contemplated the deed, they were utterly bewildered and suffered a double torment over these events: for they were overcome by the sufferings of their countrymen. Those who imagined that the danger had not drawn near to them endured over a longer period of time the trial of those who were already caught up in the midst of vexations. Others desisted from their grievous boding once the evil, which in the past they had turned over in their minds, had materialized. Those who always were able to foresee the future with knowledge of its dangers as though it were the present were robbed of sleep at night, and during the day their conscience was pricked with every kind of torment. Strangest of all, it was not only these men whose inner faculty of judgment was troubled because they prayed and wished for no good to come to Andronikos who suffered; so also did they to whom he was devoted and ever granted some boon; for they were all suspicious of his treacherous nature and the fickleness of his mind. Moreover, they feared his eagerness to inflict punishment, nor could they ignore the acute danger to themselves.

Our history must not pass over the following. Certain outspoken persons made bold to ask Andronikos for permission to take down the bodies of the hanged men. And he, like Pilate with reference to the God-Man, asked if they had been dead a while;` informed by the hang-men that they had perished miserably, he said that he deemed them worthy of pity, weeping as he spoke, and asserted that the severity and authority of the law were stronger than his own impulse and disposition to do otherwise and that the judges' sentence superceded his own choice of action.

O teardrops, shed by those of old and ourselves in the affliction of our souls, showering down on our hearts as from a cloudburst! 0 portent of greater sorrow and unequivocal proof of inner distress! Sometimes they flow or trickle from the tearducts from joy, but this was not the case with Andronikos, for whom the flow of tears presaged certain death. 0, the

light of how many pupils have you extinguished with your hot flow? 0, how many have you swept along to Hades in your torrential downpour? 0, how many have you washed away in your deluge! 0, what manner of men have you dispatched to their graves as their very last bathwater, or as a drink-offering made over their tombs and poured out as the last libation?

In this wise did Andronikos remove Constantine Makrodoukas and Andronikos Doukas from the world of the living, and both men learned in what fashion he repaid his debts for favors rendered. Not long after- wards, he hanged the two Sebasteianos brothers on the opposite shore of the straits called Perama on the grounds that they had conspired to take his life [summer 1184].

Andronikos continued to occupy himself with these and many other, and even worse, crimes. Alexios Komnenos, who was cupbearer to Manuel Komnenos and a scion of the same family (for he was his brother's son), was condemned by Andronikos to banishment among the Cumans, from whom he escaped like a flying serpent, so to speak, and arrived in Sicily. When he appeared before William, the tyrant of that island, he revealed his identity. With him was Maleinos from the province of Philippopolis, a man neither notable for his family, illustrious in station, nor distinguished by profession."' The wrath of both men against Andronikos made them labor strenuously to the injury of their own coun- try: Alexios made his charge perhaps with some justification, but Maleinos simply obliged Komnenos and exerted himself to appear to those who did not know better that he was one of those who merited respect. They did not relate these things only for the ear of the king but also before large numbers and won them over. They very nearly caressed the soles of the king's feet and like fawning dogs licked them with their tongues, not so much that Andronikos might be made to suffer miserably but that the tyrant of Sicily might be instigated to seize the Roman provinces as though they were a ready prey.

William was incited by their words. Moreover, he had often heard identical reports from his fellow Latins who had served in the past as mercenaries with the Romans and had rubbed shoulders in the imperial court but then were scattered hither and yon because of the indifference of the hardhearted and merciless Andronikos.812 Marshaling his military forces in full array, he selected a large number of mercenaries whom he enthused with large stipends and swollen promises and thus enrolled thousands of knights. He transported his land force to Epidamnos813 and took the city without a blow [24 June 1185, Feast of St. John the Baptist]. Directing the naval force to sail straight to the seaports of Thessaloniki, he seized the provinces along the way as they capitulated.

In concert, the land [6 August 1185] and sea forces [15 August 1185] seized and girded the splendid city of Thessaloniki with the taslet of Ares. The city was taken by siege and a few days later [24 August 1185]815 admitted the enemy within, not because the defenders were helpless and unskilled in warfare, but because of the betrayal of the strategos David Komnenos.816 The Thessalonians saw no valor in the man; in his constant dread of Andronikos he was most adroit only in seeking ways to escape his irresistible hands817 by hiding, if needs be, beneath the waves of the sea, or by losing himself among steep crags, or by hiding out on mountains or in caves, or else in being swallowed up by some monster of the deep as was the fugitive prophet [Jonah]."' He did not take it upon himself to do anything. It was the misfortune of the Thessalonians that he who was appointed governor and inglorious commander of the troops, that he who was more effeminate than woman and more cowardly than the deer, taking his and the city of Thessaloniki's future captors by sur- prise, should openly summon the enemy while they were still a good distance away and with premeditation place himself in their hands as a willing captive.

Moreover, when the battle was under way and all manner of weapons and siege engines were employed against the city, he remained a spectator rather than an antagonist of the enemy troops; neither was he observed throughout the entire siege sallying forth even though the city's defenders forcefully roused him to do so, nor did he submit to do their bidding but instead stifled the citizens' fervor like a worthless hunter holding back the courageous onrush of his whelps. Accordingly, absolutely no one saw him dressed in his suit of armor; rather, he shunned helmet, coat of mail, greaves, and shield like those tenderly reared ladies who know nothing outside their shaded women's apartments, and he made the rounds of the city mounted upon a mule with his mantle gathered and fastened from behind, wearing elegant gold-embroidered buskins reaching to the ankles.820 When the siege engines smote the walls, bringing the stones crashing down to the earth, David laughed at the whistling sound made by the stone missiles and the thunderous clap as they struck the wall. As the walls fell in ruins from the breaches, he remarked to the good-for-nothing little fellows in his company, squeezing himself beneath a sturdy arch in the meantime, "I listen to the old lady's bellowing"; so spoke he who still had need of a nurse, and thus he called the largest of the siege engines whose stone missiles hurtled forth from its fitting to demolish the city's walls.

Such then was the traitor unfortunately assigned to guard Thessaloniki; allotted a pirate for pilot and a sorcerer for physician, the city capitulated after putting up a brief resistance.

The evils which ensued were another succession of Trojan woes sur- passing even the calamitous events of tragedy,S23 for every house was robbed of its contents, no dwelling was spared, no narrow passageway was free of despoilers, no hiding place was long hidden. No piteous creature was shown any pity; neither was any heed paid to the entreaty, but the sword passed through all things, and the death-dealing wound ended all wrath. Futile was the flight of many to the holy temples, and vaintwas their trust in the sacred images. The barbarians,824 who confused divine and human things, neither knew how to honor the things of God nor to grant sanctuary to those who ran to the temples; the same fate which befell those who stayed in their common dwellings, namely, quick death dealt by the sword or being stripped bare of all possessions which the plunderers considered the greatest beneficence, met those who fled to the temples for refuge-not to mention the even more calamitous circumstance, the terrible affliction of the soul caused by the press and conges- tion of the throngs that entered the holy temples.825 Bursting in upon the sanctuaries with weapons in hand, the enemy slew whoever was in the way, and as sacrificial victims mercilessly slaughtered whomever they seized [the clergy].

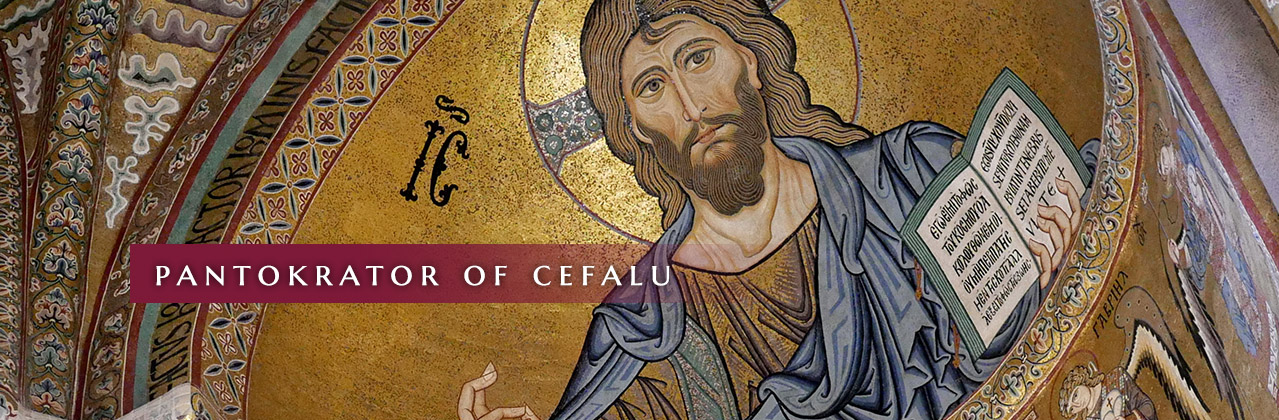

How could men who defiled the divine and took absolutely no heed of God be expected to spare human life?826 It was less novel that they plundered the votive offerings to God, placed profane hands on the sacred, and looked with shameless eyes upon those things forbidden to be seen than it was unholy to have dashed the all-hallowed icons of Christ and his servants to the ground; firmly planting their feet on them, they forcibly removed their precious adornments and then threw the icons out into the streets to be trampled under foot by the passers-by, or they cast them into the fire to cook their food. Even more unholy, and terrible for the faithful to hear, was the fact that certain men climbed on top of the holy altar, which even the angels find hard to look upon, and danced thereon, deporting themselves disgracefully as they sang lewd barbarian songs from their homeland. Afterwards, they uncovered their privy parts and let the membrum virile pour forth the contents of the bladder, urinating round about the sacred floor; they performed these lustral besprinklings for the demons, improvising hot baths for the avenging spirits through which they swam with great effort and thereby contriving great misfortunes for mankind and inflicting dreadful sufferings.

When it was time to put an end to the horrors and for the hostilities to cease, the Sicilian commanders rose up to restrain the murderous onrush of the majority. One of the commanders, on horseback and clad in heavy armor, entered the temple of the myrrh-bearing martyr [Saint Demetrios]; some he smote with the flat side of his sword, and on others he 1 inflicted wounds, but he was barely able to stay the course of evil. These evils were not sufficient unto the Thessalonians, for if the day following the fall put an end straightway to the casting of the besieged down into the House of Hades, the subsequent afflictions pressed the wretched survivors in myriad other ways to seek the end of life and to prefer death to life, so that like sorely pressed Job, many prayed for death and obtained it not.

And every other Latin soldier who took captive his opponent in battle ill-treated him and showed him no mercy. He perpetrated every evil proposed by the arrogance of victory; he robbed his adversary, and, subjugating him, inflicted injury that was indeed intolerable, defying description. Even if the Roman seized could speak the Italian language perfectly, he was nonetheless so far estranged from this alien race that not even his dress had anything in common with the Latins; it was as though he were detested by God, condemned to drink unmingled the

Lord's cup of wrath and to take the cup unmixed. What death-dealing viper, or deadly heel-menacing serpent, or bull-killing lion does not overlook stale meat when sated with fresh game? Thus did Latin inhumanity wreak ruin, taking live captives; it was not moved to pity by supplications, softened by tears, or gladdened by cajolery. And should someone sing a pleasant tune, it was regarded as the shriek of kites or the cawing of crows. Should the music be so beguiling that even rocks were made to rise up, as happened with Orpheus's melodies, for naught did the lyre player strike the chord, and in vain did he lift up his voice in sweet song. Should the barbarian succumb to the song as though it were the swan's dying and honor-loving song, his relentless soul would alter it, once more effecting death and remaining as implacable as before, or obdurate before every supplication like an unyielding anvil.83' The members of his race knew how to indulge his singular wrath and were disposed to submit to his irate commands.

What unending evil was permitted this Roman-hater, and what animosity he had stored in his heart against every Hellene! Even the serpent, the ancient plotter832 against the human race, did not conceive and beget such enmity. But because the land which was our allotted portion to inhabit, and to reap the fruits thereof, was openly likened to paradise by the most accursed Latins, who were filled with passionate longing for our blessings, they were ever ill-disposed toward our race and remain forever workers of evil deeds. Though they may dissemble friendship, submitting to the needs of the time, they yet despise us as their bitterest enemies; and though their speech is affable and smoother than oil flowing noise- lessly, yet are their words darts,833 and thus they are sharper than a two-edged sword.834 Between us and them the greatest gulf of disagree- ment has been fixed,835 and we are separated in purpose and diametrically opposed, even though we are closely associated and frequently share the same dwelling. Overweening in their pretentious display of straightfor- wardness, the Latins would stare up and down at us and behold with curiosity the gentleness and lowliness of our demeanor; and we, looking grimly upon their superciliousness, boastfulness, and pompousness, with the drivel from their nose held in the air, are committed to this course and grit our teeth, secure in the power of Christ, who gives the faithful the power to tread on serpents and scorpions and grants them protection from all harm and hurt.836

And now to continue with the sequence of events. The Sicilian forces which entered the city of Thessaloniki and committed their godless crimes began the siege on the sixth day of the month of August, in the third indiction, in the year 6693 [1185], and ended it on the fifteenth day of the same month without sustaining any injury whatsoever.

It was not, as we have said, only during the first days of the siege that the Thessalonians suffered the worst possible atrocities; even when it was over, the scale of fortune did not incline towards humanity, nor did their captors look upon them kindly. They appropriated the dwellings, expelling their masters and depriving them of the treasures stored within, and they also removed their clothing, not even refraining from taking their last undergarments, which conceal what nature has commanded to be covered as unseemly. Nor did they dispense to the masters any morsel of the fruits of their labors into which they had entered, and they made merry all day long. Those who had gathered in the dainties of cuttlefish were left to wander about hungry in the streets, barefoot and without tunic, to sleep upon the earth; and they who heretofore were dressed in fine garments now had the ground for their bed, the sky as their roof, and a dungheap as their comfortable couch. Of all those things related, that which was the worst and afflicted the very soul was not permitting the masters to enter their houses. Should one do so at any time or merely put his head inside, he was seized by those within as though by the ancient evil of Skylla.839 He was questioned and repeatedly asked his reason for coming thither, or for casting a glance inside, or for stepping on the threshold of the outer door, and he was given many lashes and compelled to give over monies which he was suspected of having hidden there. Pretending to pour out his heart to them, cowering, so to speak, under their boasts, and looking round timidly, he was led out of the dwelling; while afraid lest he be despoiled, yet he was eager to learn whether that place in the house wherein he had hidden his coins had escaped the notice of the enemy who made a most diligent search to find them, or whether he had succeeded in keeping them safe and undetected. Often, when someone did hand over the money he had concealed, with the expecta- tion that he would be released from his own house, he still was not spared lashings and the blows were multiplied; and tortures of diverse kinds were inflicted so that he should reveal even more hidden treasures. And should someone who had nothing to give maintain earnestly, now as before, that he was indigent and explain that, as he was passing by this particular street, he had had a compelling desire to see his paternal home or the house he himself had built at heavy expense, now being both spectator and mourner of his former estate and effects, there was none to show him mercy or to rescue him.840 Such a man would be subjected to torture and torments; he would be suspended by the feet, a heap of chaff would be placed under him and ignited, and he would be blackened by the smoke. His mouth would be smeared with dung, his ribs pierced by arrows, and being subjected to a host of other punishments, he would either give up the ghost as the result of these sufferings or would be dragged out by the feet, half dead, as so much garbage from the house, and would lay ex- posed in the open square.84'

What then? If the Sicilians welcomed the former masters of the houses with such kindnesses and paid them court in this fashion, did they per- chance admit with tender feeling and treat with kindheartedness the rest, who passed by their dwellings as though they were the mouths of caves leading down into hell, or the Cretan labyrinth, or the Laconian pit?12 Not at all! How could it be otherwise with such men who were more savage than the wild beasts, and who were wholly ignorant of the mean- ing of pity, and who rejoiced over human calamities? Like dogs, the victims drew back from those who overtook them and did not molest them with their teeth, but crouched before their pursuers without even barking and voluntarily shut their jaws. The Sicilians confiscated any property that they reckoned to be of great value843 and turned it aside to their ways,844 squandering it on harlots845 and nearly coming to blows with each other. So far were these men from having pity on their victims- these men who boasted that they would seize the entire Roman empire as a deserted brood of chicks and lay hands on her as on abandoned eggs -that they were moved to laughter over the nakedness of so many; they were convulsed with uncontrolled guffaws whenever someone emaciated from hunger passed by with swollen abdomen, sallow and corpselike from feasting on vegetables and banqueting only on bunches of grapes gathered in fear from the nearby vineyards. Thus did they take pity on those who wore tattered garments and covered those parts of the body which needs to be hidden with rush mats, while with the stems of the rush they plaited coverings to provide shade for the head. And when they met these creatures in the streets, the Latins, with grinning laughter, would grab their beards with both hands and pull the hair on their heads, contending that these were unbefitting; they ridiculed the shagginess and length of the beard and insisted that the hair be clipped round about according to their own style.' Whenever they rode through the market- place on horseback, they would brandish their ashen spears and knock down any poor wretch in their way. Should there be a mire or a mud puddle nearby on the same side of the street, they would push them in, for they deemed such chance meetings as producing no good, and so they shoved them aside with great loathing and blocked their way. Should the Romans at any time eat coarse barley bread or any other food which sustains the human body, they would come upon them without warning and mock them, knock over their bowls, and kick over the table to ruin the meal. They would not allow them to draw nigh the time's bread of grief,848 or approach the mixed cup of wine turned sour, or take the cup which had received the cistern's thirst-quenching water. These utterly shameless buffoons, having no fear of God whatsoever, would bend over and pull up their garments, baring their buttocks and all that men keep covered; turning their anus on the poor wretches, close upon their food, the fools would break wind louder than a polecat.849 Sometimes they discharged the urine in their bellies through the spouts of their groins and contaminated the cooked food, even urinating in the faces of some, or they would urinate in the wells and then draw up the water and drink it. The very same vessel served them as chamber pot and wine cup; without having been cleansed first, it received the much-desired wine and water and also held the excreta pouring out of the body's nozzle.

Nonetheless, the Sicilians so honored the servants of God who are accounted among the firstborn,85' took such heed of the miracles they wrought, and were so astonished at the marvelous and novel wonders by which Christ glorifies those who with their own bodies have glorified him85z that they would collect in jars and basins the unguent which exuded , from the crypt of Demetrios-who was renowned in miracles and among `. martyrs-and pour it over their fish dishes; they would rub their leather footgear with this sweet oil and use it for all the purposes which olive oil now serves. The unguent issued forth as from an inexhaustible fount, or gushed out as from a great deep in a most novel manner, so that even the barbarians deemed the phenomenon a miracle, and they were amazed by the grace which the martyr received from God. Even when the time was sounded for the Romans to assemble in the temples for the singing of hymns, the boorish members of the army did not keep away, but went inside as though to attend church services together with the Romans, to offer up to God a sacrifice of praise. They did no such thing, but instead, babbling among themselves and bursting forth in unintelligible shouts or violently throttling certain Romans be- cause of some incident, they caused a great disturbance and confounded the hymn, so that it seemed as though the chanters were singing in a strange land854 rather than standing in the temple of God. In response to those who were praising the Lord, many would let loose with ribald songs, and, barking like dogs, they would break in upon the hymn and drown out the supplication to God.

Nonetheless, the Sicilians so honored the servants of God who are accounted among the firstborn,85' took such heed of the miracles they wrought, and were so astonished at the marvelous and novel wonders by which Christ glorifies those who with their own bodies have glorified him85z that they would collect in jars and basins the unguent which exuded , from the crypt of Demetrios-who was renowned in miracles and among `. martyrs-and pour it over their fish dishes; they would rub their leather footgear with this sweet oil and use it for all the purposes which olive oil now serves. The unguent issued forth as from an inexhaustible fount, or gushed out as from a great deep in a most novel manner, so that even the barbarians deemed the phenomenon a miracle, and they were amazed by the grace which the martyr received from God. Even when the time was sounded for the Romans to assemble in the temples for the singing of hymns, the boorish members of the army did not keep away, but went inside as though to attend church services together with the Romans, to offer up to God a sacrifice of praise. They did no such thing, but instead, babbling among themselves and bursting forth in unintelligible shouts or violently throttling certain Romans be- cause of some incident, they caused a great disturbance and confounded the hymn, so that it seemed as though the chanters were singing in a strange land854 rather than standing in the temple of God. In response to those who were praising the Lord, many would let loose with ribald songs, and, barking like dogs, they would break in upon the hymn and drown out the supplication to God.

To make a long story short, these were the sufferings of the besieged Thessalonians which certain authors have described in their own detailed account of the historical events' When he who dwells in the high place and looks on the low things looked down from heaven858 and saw that none of the captors understood or sought after God, and that they all had become good-for-nothing and had turned to lawless deeds, he resolved to mock them, to destroy them utterly, to trouble them in his own fury, and to take pity on the afflictions of his own people,"' to award them the prize of freedom, giving heed to their grieving spirit, and not to set at nought their broken hearts. He shortens, it seems to me, the long duration of woes for his chosen people, and those things with which before he had violently threatened the Babylonians for showing no mercy to Sion and her delicate sons and daughters in their abduction and captivity, he visited upon them [the Babylonians] in an instant. And the Lord was glorified as never before in the testimony of his martyrs,86' and he magnified his own mercy868 at that time, moved, it seems, by litanies and by hearkening to the prayer of the archbishop of Thessaloniki.

This man was Eustathios, who was renowned the world over for his learning and virtue, for his praiseworthy and beseeming prudence, and for his admirable and quite remarkable depth of experience, who was by far superior to others in eloquence and every kind of wisdom, both sacred and profane, a brimming mixing bowl with its own peculiar and extraordinary style. He chose to suffer affliction with his own flock, rather than to emulate the hired hands, who when the wolves come abandon their flocks and flee.B7' Although it was possible for him to emigrate when the approach of the enemy was awaited and before they had invested the city, he could not justify to himself such an action, for by remaining he could save many. Willingly shutting himself in the city, he shared the afflictions of the sufferers to the end, so as to persuade them with his own example; to exhort them to suffer the chastisements of God as though they were but the stings of a gentle father and to await healing again from him who smiteth. "For if he knows," Eustathios said, "how to smite often, he is also wont to heal much more often. Indeed, if one bears his afflictions meekly and thankfully, and is not so disgusted by bitter anguish as to become devoid of all affection for him who visits these things upon him, and submits with sighs to Providence, that man is freed from the depth of divine judgments, having learned to give thanks to the Lord who alone dost well to him; it is as though the ship of life, borne by fair winds, carries to him the objects of his desire, smoothly and easily, and without shipwreck in the manner of ships bringing their cargoes from afar."

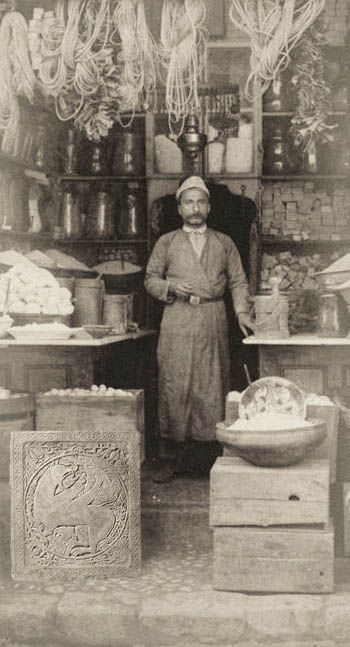

Shops operated from columned porticos. Merchandise was offered on the street and within the store. Most shops were family operated.

Shops operated from columned porticos. Merchandise was offered on the street and within the store. Most shops were family operated. Constantinople was served by aqueducts to fountains and open air cisterns around the city. Fountains would have been decorated with ancient statues and sculpture like this. People drew much of their water from wells that accessed underground cisterns.

Constantinople was served by aqueducts to fountains and open air cisterns around the city. Fountains would have been decorated with ancient statues and sculpture like this. People drew much of their water from wells that accessed underground cisterns. The city had many gardens and even vineyards. Many of the streets were arcaded.

The city had many gardens and even vineyards. Many of the streets were arcaded.

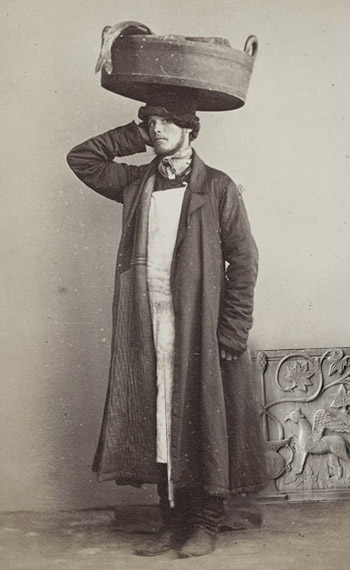

The streets were full of people who delivered fresh and prepared foods or every kind. Water was also delivered right to your door.

The streets were full of people who delivered fresh and prepared foods or every kind. Water was also delivered right to your door. Constantinople was a late antique city of columns, forums and paved streets. Some streets and shops were lit at night.

Constantinople was a late antique city of columns, forums and paved streets. Some streets and shops were lit at night. There were many priests, monks and nuns. Aristocrats and rich merchants founded and endowed convents for the female members of their family to retire to. Not all of them became nuns. Women could spend long periods of time living in nunneries as places of refuge.

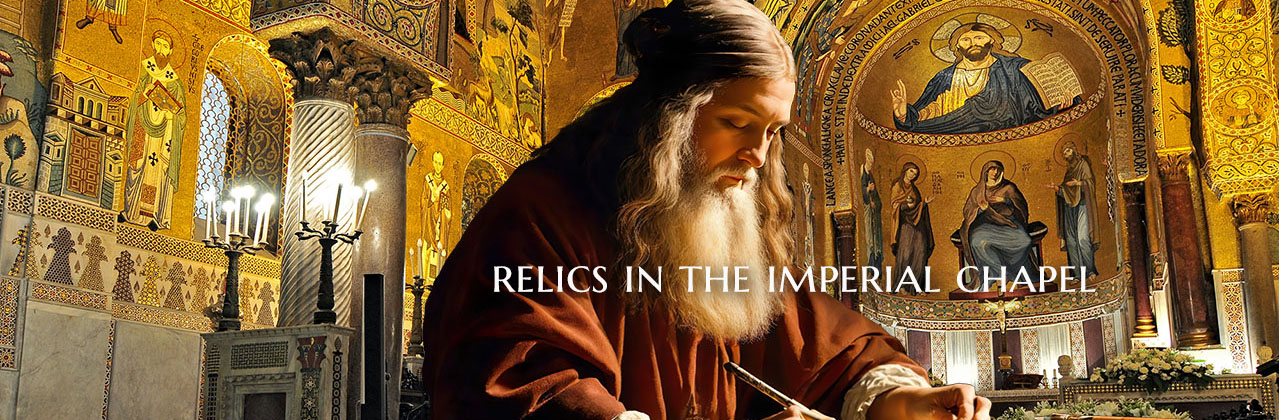

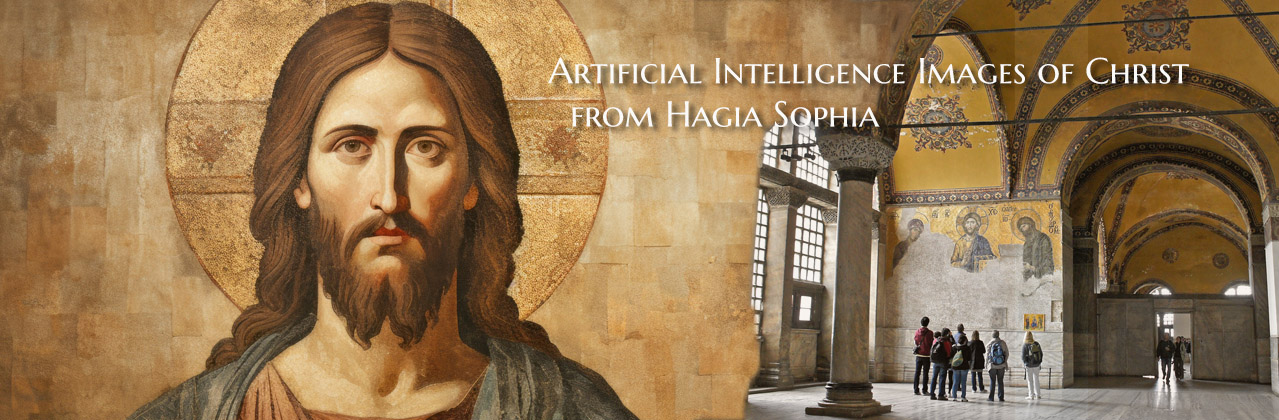

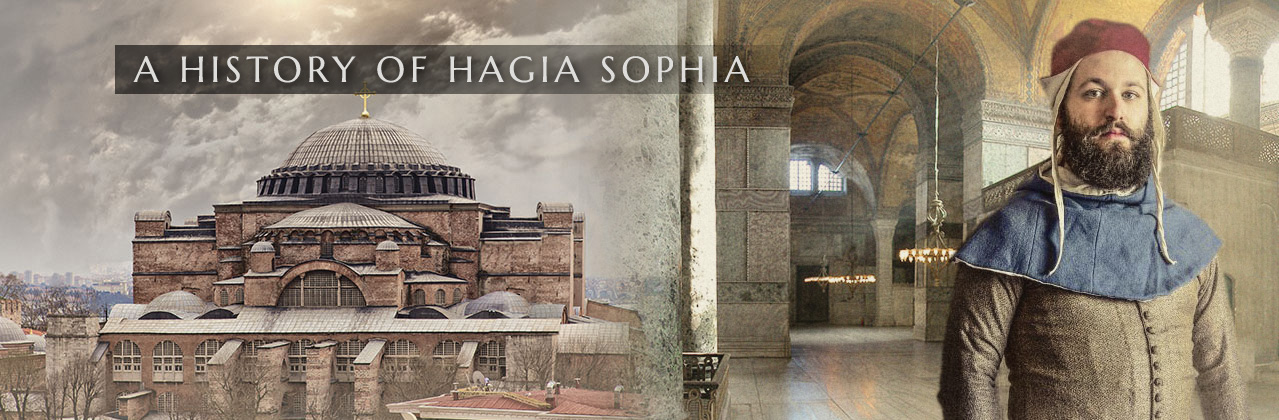

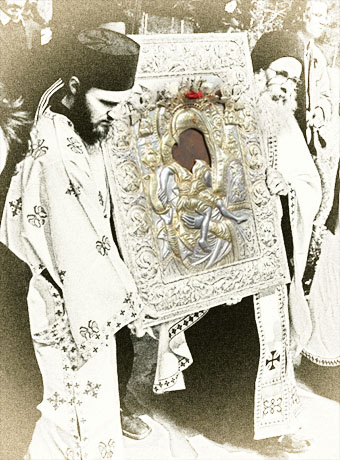

There were many priests, monks and nuns. Aristocrats and rich merchants founded and endowed convents for the female members of their family to retire to. Not all of them became nuns. Women could spend long periods of time living in nunneries as places of refuge. The city was the destination of pilgrims from all over the world. Every year, at Easter, the relics of Christ's Passion were exhibited in Hagia Sophia. Hundreds of thousands of people viewed them.

The city was the destination of pilgrims from all over the world. Every year, at Easter, the relics of Christ's Passion were exhibited in Hagia Sophia. Hundreds of thousands of people viewed them. Women were very involved in the production of textiles and clothing. They also operated shops.

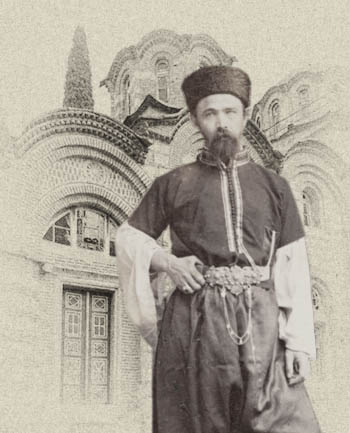

Women were very involved in the production of textiles and clothing. They also operated shops. Fashions changed rapidly in the 12th century. Men's fashions could be outlandish - even foppish. All men wore hats or turbans. Belts were decorated with buckles of bronze, silver and gold.

Fashions changed rapidly in the 12th century. Men's fashions could be outlandish - even foppish. All men wore hats or turbans. Belts were decorated with buckles of bronze, silver and gold. Imperial clothing was made in specialized shops near the Great Palace.

Imperial clothing was made in specialized shops near the Great Palace. Women wore beautifully ornamented clothes. Much of this work was done at home. Byzantine women were expert seamstresses and tailors.

Women wore beautifully ornamented clothes. Much of this work was done at home. Byzantine women were expert seamstresses and tailors. Hauling water and food was a hard job which was done by both men and women. Many of them could serve you wine, bread or fried delicacies in the streets. Some of them were attached to taverns.

Hauling water and food was a hard job which was done by both men and women. Many of them could serve you wine, bread or fried delicacies in the streets. Some of them were attached to taverns. Most Constantinople homes had courtyards. Residents would get water here, do cooking or their washing here. Since people normally lived in family compounds or near their work these activities could be communal.

Most Constantinople homes had courtyards. Residents would get water here, do cooking or their washing here. Since people normally lived in family compounds or near their work these activities could be communal.

THUS did Emperor Alexios disappear from the world, not yet fifteen years of age. He had reigned for three of these years, but not alone and unaided, for as he was but a child, his mother at first governed the realm, and then the affairs of the empire were administered by two tyrants. It was as though the sun were hidden behind the clouds, and it seemed as though Alexios was subject instead of ruler, commanding and doing whatever the rebels proposed until his life was choked out.

THUS did Emperor Alexios disappear from the world, not yet fifteen years of age. He had reigned for three of these years, but not alone and unaided, for as he was but a child, his mother at first governed the realm, and then the affairs of the empire were administered by two tyrants. It was as though the sun were hidden behind the clouds, and it seemed as though Alexios was subject instead of ruler, commanding and doing whatever the rebels proposed until his life was choked out. Hence, since the Divinity's will was contrary, he was seized and sent to Andronikos by those very men whom he hoped would help preserve him unharmed and enable him to work great and noble deeds, those men in whose might of hand and soul he had trusted to find every kind of support in overthrowing Andronikos. These were figments of a deluded imagination and proved to be dream-like apparitions. At Atramyttion, he was apprehended by a certain Kephalas, a man of great power and the tyrant's most trusted supporter, and he was entrusted into the hands of Andronikos as a sacrificial victim. His eyes were gouged out, and he was cast into the Monastery of Pantepoptes. There Lapardas lamented the

Hence, since the Divinity's will was contrary, he was seized and sent to Andronikos by those very men whom he hoped would help preserve him unharmed and enable him to work great and noble deeds, those men in whose might of hand and soul he had trusted to find every kind of support in overthrowing Andronikos. These were figments of a deluded imagination and proved to be dream-like apparitions. At Atramyttion, he was apprehended by a certain Kephalas, a man of great power and the tyrant's most trusted supporter, and he was entrusted into the hands of Andronikos as a sacrificial victim. His eyes were gouged out, and he was cast into the Monastery of Pantepoptes. There Lapardas lamented the  Not long afterwards, Lapardas departed this life. Andronikos had been so frightened by his defection that all throughout Lapardas's flight he had been haunted by his own imminent destruction; he had feared him be- cause he was sudden and quick to give battle and distinguished by manly courage. In the realization that no headway was being made against him by continued pursuit or by armed combat, the contriver had devised a novel stratagem. He had sent to the governors of the eastern provinces imperial letters whose contents truly spoke in wickedness: Andronikos contended that he had sent Lapardas to Asia and that whatever actions Lapardas should undertake, even though unclear to most in purpose, would be done according to plan and on behalf of his rule, and he urged all to welcome him without hesitation. Andronikos's intent was to thwart thereby the onrush of many who were suspicious as to why Lapardas had resolved to oppose Andronikos and was marching out the ranks of warriors769 as his adversary. Andronikos testified to the rebel's loyalty and commanded that the fugitive be welcomed as though sent by him. But even if these novel letters effectively achieved their purpose, it was im- possible to foresee how quickly the man would be taken.

Not long afterwards, Lapardas departed this life. Andronikos had been so frightened by his defection that all throughout Lapardas's flight he had been haunted by his own imminent destruction; he had feared him be- cause he was sudden and quick to give battle and distinguished by manly courage. In the realization that no headway was being made against him by continued pursuit or by armed combat, the contriver had devised a novel stratagem. He had sent to the governors of the eastern provinces imperial letters whose contents truly spoke in wickedness: Andronikos contended that he had sent Lapardas to Asia and that whatever actions Lapardas should undertake, even though unclear to most in purpose, would be done according to plan and on behalf of his rule, and he urged all to welcome him without hesitation. Andronikos's intent was to thwart thereby the onrush of many who were suspicious as to why Lapardas had resolved to oppose Andronikos and was marching out the ranks of warriors769 as his adversary. Andronikos testified to the rebel's loyalty and commanded that the fugitive be welcomed as though sent by him. But even if these novel letters effectively achieved their purpose, it was im- possible to foresee how quickly the man would be taken. With the coming of spring [1184] he attended the horse races and spectacles and then assembled all the troops, those from the western and eastern armies who had not rebelled, and took the road leading directly to the city of Nicaea. He dispatched Alexios Branas, who had returned from the regions of Branicevo, with a large force to be drawn out in battle array around Lopadion. The Lopadians had already joined their neighbors, the Nicaeans and the Prusaeans, in revolt. Since the expedition fared well for Branas and he had brought a successful conclusion to the campaign, he continued on to Nicaea, where he joined forces with Andronikos. When both armies were gathered together into one force, Andronikos determined to assault the city. The defenders were insolent, not only when Andronikos was absent, but they also scorned him when he was present; appearing on the wall, they defended themselves with weapons and delivered blows of vulgarities, sparing neither missile nor obscenity. The gates of the city were shut and securely bolted, but the gates of the lips opened wide, and the defenders' tongues issued forth from the breastworks of the teeth to discharge missiles of scurrilities against Andronikos. Cut to the quick by such darts, he breathed forth a fire of wrath,"` forcing out a Typhonian blast, and was unable to contain his resentment, for the city of Nicaea boasted to be impregnable, or very nearly so, thanks to her mighty walls built all of baked bricks. At that time, soldiers who abhorred Andronikos streamed into the city. Among these were Isaakios Angelos, who later put an end to Andronikos's tyranny and held sway over the Romans after him, and Theodore Kantakouzenos, as well as Turks who were invited inside, all of which seemed to him to bode no good for the besiegers.