The author of the Turkish Taj-ut-Tavarikh or ‘Crown of History,’ written by Khodja Sad-ud-din, states that after the sultan’s troops had forced a way into the city—not, as he is careful to explain, through any of the gates, but across the broken wall between Top Capou and the Adrianople Gate—they went round and opened the neighbouring gates from the inside, and that the first so opened was the Adrianople Gate. Then the army entered through these gates in regular order, division by division.

While the principal assault was that made under the sultan’s own eyes in the Lycus valley, the city had been elsewhere simultaneously attacked. Though all other attacks sink into insignificance beside this, yet they are deserving of notice. The most important were those made by Zagan Pasha 359from one or more large and specially constructed pontoons which had been brought as close as possible to the walls at the western end of the Golden Horn and by Caraja Pasha between the Adrianople Gate and Tekfour Serai.

Attacks by Zagan and Caraja fail.

Zagan had brought all his division across the bridge near Aivan Serai, and his soldiers, during the early morning, had made a continuous series of attempts to scale the walls from the narrow strip of land between them and the water, while his archers and fusiliers attempted to cover the attacking parties from the pontoons. His efforts were aided by the crews on board the seventy ships which had been transported across Pera Hill and which were now stationed at intervals extending from the pontoons to the Phanar. They were stoutly and successfully opposed by Gabriel Trevisano, who had charge of the walls upon the Horn as far as the Phanar.459

Caraja’s vigorous assault, as has been already mentioned, was at one of the three places where Mahomet boasted that his cannon had made a way into the city. It was probably a part of his division which had followed the discoverers of the open Kerkoporta into the city. Zagan and Caraja were, however, defeated.

By fleet also.

The Turkish fleet under Hamoud had done its part elsewhere. During the night it had come in force to the boom and had taken up a position parallel to it. When, however, the admiral saw that there were against him ten great and other smaller ships, all ready for the defence, he carried out the orders which had been given on the previous evening, passed round Seraglio Point, and took up a position opposite the walls on the side of the Marmora, where the caloyers or monks were among the defenders. But all the efforts of the Turks in the fleet on the side of the Marmora failed to effect an entrance. Small as was the number of the men dispersed along the walls, they held their own and repulsed all attempts to scale them. It was only when they saw the Turks in their rear that they recognised that their struggle had been in vain. Then, indeed, some flung themselves in despair from the walls; others surrendered in hope of saving their lives. The walls were abandoned. Once the Turks had succeeded in effecting their entry through the stockade in the Lycus valley, followed as such entry was by the marching in of the divisions through the ordinary gates, the defence of the city was hopeless.

Probably among the earliest from the fleet to effect an entry were men who appear to have landed at the Jews’ quarter, which was near the Horaia Gate on the side of the Golden Horn.

The two brothers Paul and Troilus Bocchiardi in the highest part of the Myriandrion, near the Adrianople Gate, maintained their resistance for some time after they had observed that the Turks were pouring in on their left. Seeing that further resistance was useless, they determined to look after their own safety and to make for the ships. In doing so they were surrounded, but fought their way through the enemy and escaped to Galata.463 Greeks and Latins alike, who were defending the walls on the Marmora and Golden Horn, judged that it was now impossible to hold them. From the latter position they could see that the Venetian and imperial flags which had waved over the towers from the Adrianople Gate down to the sea had been replaced by the Turkish ensigns. They were, indeed, soon attacked in the rear. The crews of the Turkish ships, likewise learning from the hoisting of the Turkish flags in lieu of those of St. Mark and the empire that their comrades were already within the city, made more strenuous efforts than before to scale the walls, and in doing so met with little resistance when the defenders saw the Turks on their rear.464

The church of St. Theodosia—now known as Gul Jami, or the Mosque of the Rose, still a prominent building a short distance to the west of the present inner bridge—was crowded with worshippers who had passed the night in prayers to the Saint for the safety of the city. The 29th of May was her feast, and a procession of worshippers was met and attacked by a band of Turks, who had made their way to the Plateia, probably the present Vefa. Those who took part in the procession, mostly women, were apparently among the first victims after the capture of the city.

The Greek and Italian ships had for some time, with the aid of the defenders, prevented the men from the Turkish vessels from scaling the walls. When, however, the Turkish sailors succeeded in making their entry into the city, the Christian ships began to take measures for their own safety. The neighbouring gates had been thrown open, and the Turkish sailors joined their countrymen in the plunder and slaughter. Their ships both in the Horn and on the side of the Marmora were, according to Barbaro, absolutely deserted by their crews in their eagerness after General panic throughout city. loot. The defenders fled to their homes, and Ducas regretfully observes that in so doing some were captured; others found neither wife, child, nor possessions, but were themselves made prisoners and marched off. The old men and women who could not walk with the other captives were killed and their babes thrown into the streets. From the moment it was known that the Turkish troops had entered there was a general and well-founded panic. The Moscovite says that there was fighting in the streets, that the people threw down upon the invaders tiles and any available missiles, and that the opposition was so severe that the pashas became afraid and persuaded the sultan to issue an amnesty. But the story is improbable. There were few men within the city capable of fighting except those who had been at the walls. When there became a ‘Sauve qui peut!’ these men hastened, as Ducas reports, to their homes. That many of the fugitives, even old men and women, knowing the fate before them and their children, may have fought in desperation, willing to die rather than be captured by an enemy who spared neither men in his cruelty nor women in his lust, is likely enough, but that there was362 anything like an organised resistance in the streets is incredible.465

General slaughter during half the day.

The Turks seem, indeed, to have anticipated greater resistance than they met with. They could not believe that the city was without more defenders than those who had been at the walls. This, indeed, is their sole excuse for beginning what several writers describe as a general slaughter. From the entry of the army and camp-followers until midday this slaughter went on. The Turks, says Critobulus,466 had been taunted by the besieged with their powerlessness to capture the city and were enraged at the sufferings they had undergone. During the forenoon all whom they encountered were put to the sword, women and men, old and young, of every condition.467 The Turks slew all throughout the city whom they met in their first onslaught.

The statements made by the spectators of such scenes as they themselves witnessed are apt to be exaggerations, but a Turkish massacre without elements of the grossest brutality has never taken place. The declaration of Phrantzes that in some places the earth could no longer be seen on account of the multitude of dead bodies is sufficiently rhetorical to convey its own corrective.469 So, too, is the account by Barbaro of the numbers of heads of dead Christians and Turks in the Golden Horn and the Marmora being so great as to remind him of melons floating in his own Venetian canals, and of the waters being coloured with blood.470 That many nuns and other women preferred to throw themselves into the wells rather than fall into the hands of the Turks may be true. Their glorious successors in the Greek War of Independence, and many Armenian women during the massacres in 1895–6, chose a similar fate in preference to surrendering to Turkish captors.

Probably the truth is that an indiscriminate slaughter went on only till midday. For the love of slaughter was 363tempered by the desire for gain. The young of both sexes, and especially the strong and beautiful, could be held as slaves or sold or ransomed. The statement of Leonard is therefore probably correct, that all who resisted were killed, that the Turks slew the weak, the decrepit and sick persons generally, but that they spared the lives of others who surrendered.

The Turkish historian Sad-ud-din says, ‘Having received permission to loot, they thronged into the city with joyous heart, and there, seizing their possessions and families, they made the wretched misbelievers weep. They acted in accordance with the precept, “Slaughter their aged and capture their youth.”

The brave Cretan sailors, who were defending the walls near the Horaia Gate, took refuge in certain towers named Basil, Leo, and Alexis. They could not be captured, and would not surrender. In the afternoon, however, their stubborn resistance being reported to the sultan, he consented to allow them to leave the city with all their belongings, an offer which they reluctantly accepted. The Cretans seem to have been the last Christians who quitted their posts as defenders of the city.

Flight towards ships.

The panic caused by the morning’s massacre was general. Men, women, and children sought to get outside the city, to escape into the neighbouring country, or to reach the ships in the harbour. Some were struck down on their way; others were drowned before they could get on board. The foreigners naturally made for their own ships. Some of them have placed on record the manner of their escape. Tetaldi says that ‘the great galleys of Romania remained473 till midday trying to save what Christians they could, and receiving four hundred on board,’ among whom was one 364named Tetaldi, who had been on guard very far from the place where the Turks entered.’ He stripped himself and swam to one of these vessels, where he was taken on board. Barbaro relates that when the cry was raised that the Turks had entered the city everybody took to flight and ran to the sea in order to seek refuge in the Greek and foreign ships.

It was a pitiable sight, says Ducas, to see the shore outside the walls all full of men and women, monks and nuns, shouting to the ships and praying to be taken on board. The ships took as many as they could, but the greater number had to be left behind. The wretched inhabitants expected no mercy, nor was any shown to them. Happily, the Turks had now become keener after plunder than after Plunder organised. blood. When they found that there was no organised force to resist them, they turned their attention solely to loot. They set about the pillage of the city with something like system. One body devoted its attention to the wealthy mansions, dividing themselves for this purpose into companies; another undertook the plunder of the churches; a third robbed the smaller houses and shops. These various bands overran the city, killing in case of resistance, and taking as slaves men, women and children, priests and laymen, regardless of age or condition. No tragedy, says Critobulus, could equal it in horror. Women, young and well educated; beautiful maidens of noble family, who had never been exposed to the eye of man, were torn from their chaste chambers with brutal violence and publicly treated in horrible fashion. Virgins consecrated to God were dragged by their hair from the churches and were ruthlessly stripped of every ornament they possessed. A horde of savage brutes committed unnameable atrocities, and hell was let loose.

The conquering horde had spread themselves all over the city. For, while the regular troops had probably been kept in hand on the chance of resistance, there were others who could not be restrained from going in search of loot. Some even among the first who had entered by the Kerkoporta had 365rushed to plunder the famous monastery of the Virgin, the small chapel of which, known as the Kahriè mosque, still attests by its exquisite mosaics the wealth and artistic appreciation of its former occupants. The famous picture attributed to St. Luke was cut into strips. Others among them rushed off towards the many churches in Petra. These were, however, only a small number. It was in the afternoon of the day when the horde had entered across the broken walls and through the gates that they swept like a torrent over the city. Soon the organised bands, which had divided the city among them in order to capture the population and to seize all the gold and silver ornaments which they could lay hands on, began to amass their treasures. Old men and women, children, young men and maidens were tied together in order to mark to whom they belonged.

The loot from private houses and churches was put on one side for subsequent division and the partition was made with considerable method. Small flags were hoisted to indicate to other companies the houses plundered, and everywhere throughout the city these signals were waving, sometimes a single house having as many as ten.

St. Sophia crowded with refugees.

A body of troops more amenable to discipline than we may suppose the Bashi-bazouks to have been hastened across the city towards Saint Sophia. Many inhabitants took refuge in the churches, some probably with the idea that the Turks would recognise that the sacred buildings should afford sanctuary; others in the hope or possible belief of some kind of miraculous interference on their behalf. Ducas relates that a crowd of affrighted citizens ran to the great church of Holy Wisdom because they believed in a prophecy that the Turks would be allowed to enter the city and slaughter the Romans until they reached the column of Constantine—the present Burnt Column—but that then an angel would descend from heaven with a sword and place it and the government of the city in the hands of one whom he would select, calling upon him to avenge the people of the Lord, and that thereupon the Turks would be driven from 366the West. It was on this account, he declares, that the Great Church was, within an hour from the tidings of the entry of the Turks becoming known, filled with a great crowd who believed themselves to be safe. By so doing they had only rendered their capture more easy.

The first detachment of Turks who arrived and found the doors closed soon succeeded in breaking in. The great crowd were taken as in a drag-net, says Critobulus. The miserable refugees thus made prisoners were tied or chained together and any resistance offered was at once overcome. Some were taken to the Turkish ships, others to the camp, and the loot collected was dealt with in the same manner. The scene was terrible, but, unhappily, one which was destined to be reproduced with many even worse features in Turkish history, because, while the chief object of the Turkish hordes in 1453 was mainly to capture slaves and other plunder, the attacks on many congregations in later years, down to the time of the holocaust of Armenians at Ourfa on December 28 and 29, 1895, were mainly for the sake of slaughter. In the Great Church itself the Turks struggled with each other for the possession of the most beautiful women. Damsels who had been brought up in luxury among the remnants of Byzantine nobility, nuns who had been shut off from the world, became the subjects of violence among their captors. Their garments were torn from them by men who would not relinquish their prizes to others. Masters and mistresses were tied to their servants; dignitaries of the Church with the lowest menials. The captors drove their flocks of victims before them in order to lodge them in safety under charge of their comrades and to return as quickly as possible to take a new batch. Ropes, ribbons, handkerchiefs were requisitioned to bind them. The sacred eikons were torn down and burnt, the altar cloths, chandeliers, chalices, carpets, ornaments—indeed everything that was valuable and portable—were carried off. The greatest misfortune of all, says Phrantzes, was to see the Temple of the Holy Wisdom, the Earthly Heaven, the Throne of the Glory of God, defiled by these miscreants. One would367 hope that his story of its defilement and of the scenes of open profligacy is exaggerated. The other churches were plundered in like manner. They furnished a plentiful harvest. The richly embroidered robes, chasubles woven with gold and ornamented with pearls and precious stones, and church furniture, were greedily seized, the ornaments being torn from many of the objects and the rest thrown aside. A crucifix was carried in mock solemnity in procession surmounted by a Janissary’s cap.

While we can understand the indignation of the devout believers at the contemptuous destruction of sacred relics for the sake of the caskets in which they were contained, we can hardly regret the disappearance of the so-called sacred Wanton destruction of books. objects themselves. But it is otherwise with the destruction of books. The professors of Islam, whatever may have been their conduct in regard to particular libraries, have usually held the all-sufficiency of the Koran. That which contradicts its teaching ought to be destroyed; that which is in accordance with it is superfluous. The libraries of the churches, whatever Mahomet himself may have believed, were to the ignorant fanatical masses which followed him anti-Islamic. The only value of books was the amount for which they could be sold. Critobulus says that not only the holy and religious books, but also those treating of profane sciences and of philosophy, were either thrown into the fire or trampled irreverently under foot, but that the greater part were sold—not for the sake of the price but in mockery—for two or three pence or even farthings.477

The ships of the Turkish fleet had among their cargo, says Ducas, an innumerable quantity of books.478 In the booty collected by the Turks they were so plentiful and cheap, that for a nummus—probably worth sixpence—ten volumes were sold containing the works of Plato and Aristotle, treatises on theology and other sciences.Christian and Moslem writers agree in stating that the sack of the city continued, as Mahomet had promised, for three days. Khodja Sad-ud-din, after affirming that the soldiers of Islam ‘acted in accordance with the precept, “Slaughter their aged and capture their youth,”’ adds, with the Oriental imagery of Turkish historians: ‘For three days and nights there was, with the imperial permission, a general sack, and the victorious troops, through the richness of the spoil, entwined the arm of possession round the neck of their desires, and by binding the lustre of their hearts to the locks of the damsels, beautiful as houris, and by the sight of the sweetly smiling fair ones, they made the eye of their hopes the participator in their good fortune.

It must, however, not be forgotten that although those who took the principal part in the sack were Mahometans, yet there were also no small numbers of Christian renegades.

Numbers killed or captured.

As to the number of persons captured or killed, the estimates do not greatly differ.

Leonard states that sixty thousand captives were bound together preparatory to their final distribution. In such circumstances exaggeration is usual and almost unavoidable. But Critobulus, writing some years afterwards, estimates that the number of Greeks and Italians killed during the siege and after the capture was four thousand, that five hundred of the army and upwards of fifty thousand of the rest of the population were reduced to slavery.481

Such of the Genoese and Venetians as had succeeded in escaping from the city were preparing to get away to sea with all haste. Happily the Turkish ships had been deserted by their crews, who were busy looking after their share of plunder on shore.482 In their absence a large number of 369combatants, mostly foreigners, contrived to take refuge either on board some of the various ships in the harbour or in Galata. The Venetian Diedo, who had been appointed captain of the harbour, when he saw that the city was taken, went over to the podestà of Galata, says Barbaro, to consult whether he should get his ships away or give battle. The advice of the podestà was that he should remain until he received an answer from Mahomet by which they would learn whether the conqueror wanted war or peace with Venice and Genoa.

Panic among foreigners.

Meantime, the gates of Galata were closed, much to the disgust of Barbaro himself, who was one of the Venetians thus locked in.483 When, however, the Genoese saw that the galleys were preparing to make sail, Diedo and his men were allowed to leave. They went on board the captain’s galley and pulled out to the boom, which had not yet been opened. Two strong sailors leapt upon it with their axes and cut or broke the chain in two.

The boom was apparently very strong, for, according to Barbaro, the Turkish captains and crews, when they went ashore to plunder, believed that the Christian vessels within the harbour could not escape, because they would not be able to pass through it. The ships passed outside and went to the Double Columns, where the Turkish fleet had been anchored, but which was now deserted. There they waited until noon to see whether the Venetian merchant vessels would join them. They had, however, been captured by the Turks. Diedo, on learning this, left with his galleys. Other Venetians hastened to follow. Some of the vessels had lost a great part of their crews, and one regrets to read that the brave Trevisano was left a prisoner in the hands of the Turks. Happily for those who had reached the ships, there was a strong north wind blowing; for, says Barbaro, ‘if there had been a head wind we should have all been made prisoners.’ Seven Genoese galleys also got outside the boom and escaped. The remaining fifteen ships, which belonged to Genoa, and four galleys of the emperor, were taken by the Turks.

In Galata.

The alarm had spread to Galata, and many of its inhabitants crowded to the shore, praying to be taken on board the Genoese ships. They were ready to barter all they possessed for a passage. Some were captured on their way to the ships: among them, mothers who had deserted their children, children who had been left behind by their parents. Household goods, and even jewels, were abandoned in the mad haste to escape from the terror. The number of fugitives was far in excess of the carrying capacity of the vessels which were hastily preparing to put to sea.

Mahomet, according to Ducas, knew of the preparations and flight of many, and ground his teeth with rage because he could do nothing to prevent their escape. Zagan Pasha, to whom the Genoese, when they saw that Constantinople was captured, opened the gates of Galata,487 seeing the struggling crowd of men, women, and children attempting to get away, and probably fearing that their flight would bring war not only with Genoa but with other Western powers, went among the fugitives and begged them to remain. He swore by the head of the Prophet that they were safe, that Galata would not be attacked, and that they had nothing to fear, since they had been friendly to Mahomet. If they went away, he declared the sultan would be dangerous in his anger; whereas if they remained their capitulations would be renewed on even more favourable conditions than they had received from the emperors.

In spite of these promises, as many left the city as could. They were hardly in time, because Hamoud, the Turkish admiral, had by this time got his sailors in hand again and, the boom being already opened, entered the harbour and destroyed the Greek ships which remained. The podestà and his council went to Mahomet and presented him with the keys of Galata. He received them graciously and gave them specious promises. The report of the podestà himself, written less than a month after the capture of the city, confirms in its essential features the accounts given by Ducas, Leonard, and others of the panic which seized the population under his rule. The Turks, he says, captured many of the burgesses who had been sent to fight at the stockade. A few managed to escape across the water and returned to their families, while others got on board the ships and left the country. He himself was disposed to sacrifice his life rather than abandon his charge. If he also had left, Galata would have been sacked, and he remained to secure its safety. ‘I therefore sent ambassadors to my lord Mahomet, making submission and asking for the conditions of peace.’ No answer was sent on the first day to this request, during which the ships were getting away as fast as possible. The podestà begged their captains for the love of God and their kindred to remain at least another day, as he felt confident that he would be able to make peace. They, however, refused, and sailed during the night. The statement regarding the sultan’s anger was confirmed, for the podestà relates that Mahomet told his ambassadors, when he learned the news of the general flight, that he wanted to be rid of them all. Thereupon the podestà himself went to Mahomet, who either on the same day or shortly afterwards came into Galata and insisted that the fortifications should be so changed that the city would be at his mercy. The walls on the sea front were to be in great part destroyed: so also was the Tower of Galata—called sometimes the Tower of the Holy Cross—to which one end of the boom had been attached, and other strong portions of the defences. All the cannon were taken away from Galata and the arms and ammunition belonging to the burgesses who had fled. Mahomet promised that these should be returned to those who came back. Accordingly, the podestà sent word to Chios to the merchants and other refugees that if they returned they would receive their property. Mahomet, as a pledge of his sincerity and as the best means of convincing the Genoese of his desire to be at peace with them, granted ‘capitulations’ by which they were to retain most of the customs and privileges which they had previously obtained from the empire. They were to retain the fortress of Galata and their own laws and government; to elect their own podestà; to have freedom of trade throughout the empire, and keep their own churches and accustomed worship—but subject to the prohibition of bells—and their private property and churches were to be respected.491

Mahomet’s entry into Constantinople.

The massacre had been limited to the first day. The permission to pillage had been granted for three days. On the afternoon of the day of the capture, or possibly on the following day, Mahomet made his triumphal entry into the city. He was surrounded by his viziers and pashas and by a detachment of Janissaries. He came into the city through the gate now called Top Capou, rode on horseback to the Great Church, descended and entered. As he passed up the church he observed a Turk who was forcing out a morsel of marble from the pavement, and asked why he was thus damaging the building. The Turk pleaded that it was only a building of the infidels and that he was a believer. Mahomet had a sufficiently high opinion of the value of St. Sophia to be angry with him. He drew his sword and struck the man, telling him at the same time that, while he had given the prisoners and the plunder of the city to his followers, he had reserved the buildings for himself.

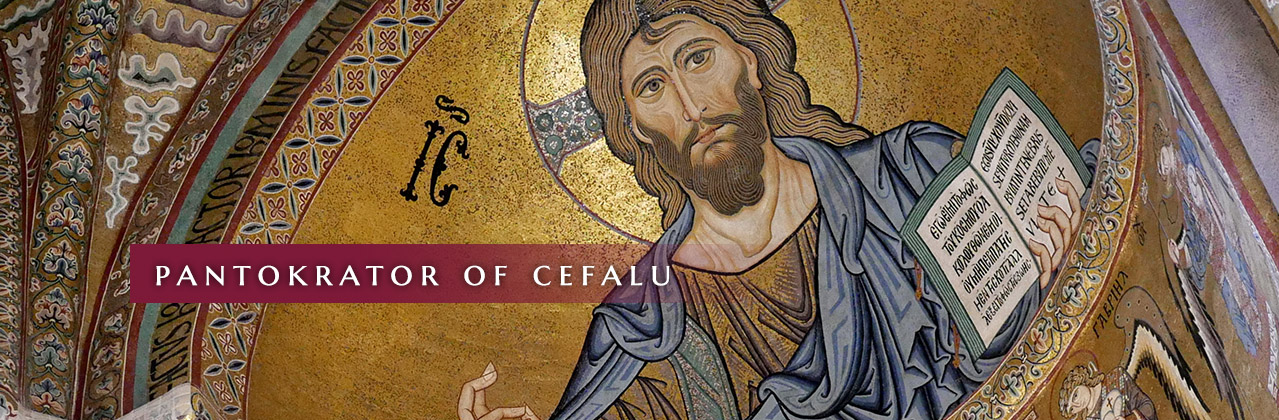

Hagia Sophia becomes a mosque.

Mahomet called for an imaum, who by his orders ascended the pulpit and made the declaration of Mahometan faith. From that time to the present, the Temple of the Holy Wisdom of the Incarnate Word has been a Mahometan mosque.

On the same day Mahomet entered the Imperial Palace, and it is said that as he passed through the deserted rooms in all the desolation resulting from the plunder of a barbarous army, he quoted a Persian couplet on the vicissitudes of mortal greatness: ‘The spider has become watchman in the imperial palace, and has woven a curtain before the doorway; the owl makes the royal tombs of Efrasaib re-echo with its mournful song.' The statement rests on the authority of Cantemir, and, whether historically correct or not, such a reflection under the circumstances is not in disaccord with what we know of the character of the young sovereign.

Fate of defenders after capture. Venetian bailey and other leading Venetians beheaded. Cardinal Isidore.

The fate of the men of most eminence among the defenders of Constantinople is illustrative of Mahomet’s methods. The bailey of the Venetians, with his son and seven of his countrymen, was beheaded. Among them was Contarino, the most distinguished among the Venetian nobles, who had already been ransomed and who in breach of faith was killed because his friends were unable to find the enormous sum of seven thousand gold pieces for his second ransom. The consul of Spain or the Catalans, with five or six of his companions, met with the same fate. Cardinal Isidore in his flight abandoned his clerical robes, and, after having been captured in the disguise of a beggar and sold into slavery, was ransomed for a few aspers.495

Phrantzes.

Phrantzes, the friend of the emperor and the historian of his reign, had an even less happy experience. He suffered the hard lot of slavery during a period of fifteen months. His wife and children were captured and sold to the Master of the Sultan’s Horse, who had bought many other ladies belonging to the Greek nobility. A year later he was able to redeem his wife. But the sultan hearing of the beauty of his daughter Thamar took her into his seraglio. She was then but fourteen years old, and died in 1454, shortly after her captivity.496 In December of 1453 his son John, in the fifteenth year of his age, preferring death to infamy, was killed by the sultan’s own hand.497

Notaras.

Most unhappy of all was the Grand Duke Notaras. He was the most illustrious prisoner, and was indeed next in rank to the emperor himself. He may be taken as a type of the old Byzantine nobility. We have seen that he had been the leader of the party which had resisted union with Rome. On account of this opposition Notaras had incurred the hostility of those who had accepted it, and as our sources of information come almost exclusively from men of the Roman faith or from those who had accepted the Union, he is not usually spoken of with favour. Phrantzes was his rival and enemy. Ducas gives two reports regarding his treatment by Mahomet. According to one, he was betrayed by a captive who purchased his own liberty by the betrayal of the Grand Duke and Orchan. At first the illustrious captive was looked upon favourably by the sultan, who condoled with him and ordered a search for his wife and daughters. When they were found, the sultan made them presents and sent them to their house, declaring to the Grand Duke that it was his intention to 375make him governor of the city and allow him the same rank that he had held under the emperor. This version is confirmed by Critobulus,498 who adds that Mahomet was dissuaded from appointing him governor of the city by the remonstrances of the leading Turks, who represented that it would be dangerous. According to the other report, Mahomet charged him with not having surrendered the city. Notaras is represented as replying that it was neither in his power nor in that of the emperor to do so, and to have made some remark which increased the suspicion and hatred which the sultan felt for his grand vizier, Halil Pasha. Whichever of these reports is correct, no hesitation is expressed by Ducas as to what followed. On the day following the interview, the sultan, after a drinking bout, sent for the youngest of the sons of the Grand Duke. Notaras replied that the Christian religion forbade a father to comply with such a request. When the answer was reported, Mahomet ordered the eunuch to return, to take the executioner with him, and to bring the youngest son together with the Grand Duke and his other son. The order was obeyed and was followed by another to put all three to death. The father asked the headsman to allow the execution of his sons to precede his own. His reason for this request, says Critobulus, was, lest his lads, being perhaps afraid to die, might be tempted to save their lives by renouncing their faith. Drawing himself up to his full height, firmly and unflinchingly, with the stateliness of an ancient aristocrat, the old noble witnessed the beheading of his two sons without shedding a tear or moving a muscle. Then, having given thanks to God that he had seen them die in the faith of Christ, Notaras bent his head to the executioner’s sword and died like a worthy representative of the proud Roman nobility. ‘For this man,’ says the same writer, ‘was pious and renowned for his knowledge of spiritual things, for the loftiness of his soul and the nobility of his life.’499

Including Notaras and his two sons, nine nobles of high rank were put to death, all invincible in their faith. The heads were taken by the executioner into the hall to show 376says Ducas, to the beast greedy of blood that his commands had been obeyed.500

Phrantzes tells the story somewhat differently. He begins his version by stating that the sultan, though elated with the great victory, nevertheless showed himself to be merciless. He makes the Grand Duke offer his wealth of pearls, precious stones, and other valuables to Mahomet, begging him to accept them and pretending that he had kept them to offer to his captor. In reply to the sultan’s question, Who had given to Notaras his wealth and to the sultan the city? the captive answered that each was the gift of God. To this the sultan retorted, ‘Then, why do you pretend that you have kept your wealth for me? Why did you not send it to me, so that I might have rewarded you? Notaras was thrown into prison, but was sent for next day and reproached for not having persuaded the emperor to accept the conditions of peace which had been submitted. Thereupon, the sultan gave the order that on the following day he and his two sons should be put to death. They were taken to the forum of the Xerolophon and the order was carried out.501 Gibbon justly remarks that neither time nor death nor his own retreat to a monastery could extort a feeling of sympathy or forgiveness from Phrantzes towards his personal enemy the Grand Duke.

The version given by Leonard is marked with the same personal hostility towards Notaras which characterises that of Phrantzes. Leonard accuses his old rival of having thrown blame both on Halil Pasha, who had always been friendly towards the emperor, and on the Genoese and Venetians. In the account given by both these writers they were reporting a version spread and probably believed by the Unionist party, as to which it is improbable that they could have had direct evidence. What is important in the narrative of Leonard is that he confirms the ghastly story of Ducas as to the demand for the youngest son by the sultan.502 The fate of the Grand Duke and his family was that which 377befell all the nobles and the chief officers of the empire. Their wives and children were generally saved, Mahomet himself taking possession for his own harem of the fairest and distributing the rest among his followers.503

Orchan.

The end of Orchan was attended by fewer circumstances of ignominy. He had defended a part of the walls near Seraglio Point. Orchan must always have anticipated death if he were captured. It was believed that the sultan had determined to kill him, as an elderly member of the reigning house, in accordance with the custom that was common in the governing family of the Turks, not only at the time in question but for at least three centuries later. Orchan, who was either the son or the grandson of Suliman the brother of Mahomet the First, had fled for safety to the emperor, who had refused to give him up and had treated him with kindness. When it was no longer possible to hold the towers which had been placed under his charge, he and the rest of their defenders surrendered. Among them was a monk, with whom Orchan changed clothes. He joined the Grand Duke, and the two lowered themselves outside the walls, but were caught by the Turks and taken on shipboard. Unfortunately, the rest of the defenders of the towers, who had been taken prisoners, were brought on board the same Turkish ship. A Greek offered to reveal Orchan and the Grand Duke if he were promised his liberty, and, having received the assurance, pointed to the man dressed as a monk and to Notaras. Orchan was at once beheaded and his head taken to Mahomet.504

The city was made a desolation. The followers of Mahomet, soldiers and sailors, left nothing of value except the buildings. Constantinople, says Critobulus, was as if it had been visited by a hurricane or had been burnt. It was as silent as a tomb. The sailors especially were active in 378destruction. The churches, crypts, coffins, cellars, every place and every thing was ransacked or broken into in search of plunder.505 Mahomet, according to the same writer, wept as he saw the ravages his soldiers had wrought, and expressed his amazement at the ruins of the city which had been given over to plunder and had been made a desert.506

All the Turks who first entered the city became rich, says the Superior of the Franciscans.507 Captives were sent in great numbers to Asia Minor either for sale or to the homes of the armed population who had taken part in the siege. Only a miserable remnant remained in Constantinople.

Affection of Constantinopolitans for their city.

The reader of the accounts of the siege, and indeed of its history generally before 1453, cannot but be struck with the attachment shown by its inhabitants towards their city. For them it is the Queen of Cities, the most beautiful, the most wealthy, the most orderly, and the most civilised in the world. There the merchant could find all the produce of the East, and could trade with buyers from all countries. There the student had access to the great libraries of philosophy, law, and theology, the rich storehouse of the writings of the Christian Fathers, and of the great classics of ancient Greece. In quietness and security, generations of monks had copied the manuscripts of earlier days free from the alarms which in Western and Eastern countries alike disturbed the scholar. The Church, the lawyers and scholars had kept alive a knowledge of the ancient language in a form in all its essential features like that which existed in the days of Pericles. Priests and laymen were proud to be inheritors and guardians of the writings of classical times and to consider themselves of the same blood as their authors. Though often almost as intolerant towards heretics as the great sister Church of the West, they did not and could not regard Aristotle and Plato, Leonidas and Pericles, and the rest of their glorious predecessors as eternally lost because they had not known Christ, and their sense of 379relationship with them helped to develop a conviction of the continuity of their history, not only with Constantine and the Roman empire, but with the more remote peoples who had given them their language. The New Rome had for a thousand years been towards all Eastern Christians all that the Elder Rome was to those in the West, and their pride in its stability and security was great. Once, and once alone, had it been captured. But the unfortunate attack made by the West in 1204, the results of which had been so correctly foreseen and foretold by Innocent the Third, had been in part overcome. This new capture was infinitely more serious. The essential difference between the two is commented on by Critobulus. By the first the city sustained a foreign domination for sixty years and lost much of its wealth. A great number of beautiful statues and other works of art, coveted by the whole world, were taken away and many more destroyed. But there the mischief stopped. The city did not lose all its inhabitants. Wives and children were not taken away. When the tyranny was past, the city recovered and once more it figured as the renowned capital of an empire, though only a simulacrum of what it had once been. It was still in the eyes of all Greek-speaking people the leader and example of all that was good, the home of philosophy and of every kind of learning, of science, of virtue, and in truth of all that is best.508 Now, all was changed: the new conquerors were Asiatics. A false religion replaced Christianity. The capital was a desert.

The city’s situation of picturesque beauty, as well as its Christian and historical associations, increased the love for it of its inhabitants and made them as proud of Constantinople as ever were the Italian citizens of Florence or Venice. It is therefore not surprising to find that, on its conquest, the grief and the rage of those who had lived in it are almost too great for words. She, says Critobulus, who had formerly reigned over many people with honour, glory, and renown, is now ruled by others and has sunk into 380poverty, ignominy, dishonour, and shameful slavery. The lamentations of Ducas are as sincere as those of Jeremiah. Its inhabitants gone; its womanhood destined to dishonourable servitude; its nobles massacred; the very babes at the breast butchered; the temples of God defiled: all present a spectacle on which he enlarges with the expression of a hope that the anger of God will be appeased and that His people will yet find favour. Unhappily, the Greek race had entered upon the darkness of the blackest night, and nearly four centuries had to pass before the dawn of their new day was at hand.

Mahomet’s attempts to repeople the capital.

At a later date Mahomet himself recognised that it was necessary to do something towards the repeopling of Constantinople. He gave orders that five thousand families should be sent from the provinces to the capital, and commanded the repair of the walls.509 It does not appear, however, that they were repaired in an efficient manner. It is generally easy to distinguish between Turkish repairs and those effected at an earlier date. Critobulus states that Mahomet ordered the renewal of those parts which had been overthrown by the cannon and of both the sea and the landward walls, which had suffered by time and weather.510 The sea walls were probably thoroughly repaired; of those on the landward side probably only the Inner Wall. Experience had shown that more than one strong wall was a disadvantage rather than otherwise. Ducas states that the five thousand families sent to Constantinople by Mahomet from Trebizond, Sinope, and Asprocastron under pain of death included masons and lime-burners for repairing the walls.

Attempts to induce Greeks to settle in capital.

In order to attract population to the capital, Mahomet recognised that it was necessary to conciliate the Greeks. It may be, as Critobulus asserts, that he felt a genuine pity for the sufferings of the captives. As a young man, with, for a Turk, quite exceptional knowledge of the literary possessions of the old world, it is easy to believe that he was desirous of satisfying the Christians, while his general intelligence must have convinced him that trade and commerce, from which a revenue was to be derived, would be much more likely to flourish with them than with men of his own race. Critobulus insists that his first intention was to employ Notaras and others of the leading Greeks in the public service, and that he recognised when it was too late that he had been misled into the blunder of putting them to death, and sent away from his court some of those who had counselled their executions, and even condemned some others to death.512 A few days after the conquest, he ordered the captives who formed part of his own share in the booty to be established in houses on the slope towards the Golden Horn. From among the noble families he selected the young men for himself. Some of these he placed in the corps of Janissaries; others, who were distinguished by their education, he kept near him as pages.513

It was during these days that Critobulus the historian sent envoys to the city, who took with them the submission of the islands of Imbros, where he was living, of Lemnos and Thasos. The archons had learned of the capture of the city. Most of them fled, fearing that admiral Hamoud, who had returned with the fleet to Gallipoli, would attack the inhabitants of the islands and treat them as he had done those of Prinkipo. Critobulus, however, sent a large bakshish to Hamoud and arranged that if the inhabitants submitted there should be no attack. Thereupon Critobulus had sent the envoys to Constantinople, with rich presents for the sultan, to make submission. The islanders were ordered to pay the same taxes to the sultan as they had formerly paid to the emperor, and thus, says the historian, 382were preserved from the great danger which threatened them.514

Mahomet published an edict within a few weeks of the capture of the city, that all of the former inhabitants who had paid ransom, or who were ready to enter into an agreement with their masters to pay it within a fixed period, should be considered free, be allowed to live in the city, and should for a time be exempt from taxes. Phrantzes states515 that even on the third day after the capture an order was issued allowing those to return who had fled from the city and who were in hiding, promising that they should not be molested. Upon the question whether on such return they would, as Critobulus relates, have to pay ransom Phrantzes is silent. A few weeks later, after his visit to Adrianople, Mahomet sent orders to various parts of his empire to despatch families of Christians, Jews, and Turks to repeople the city. He endeavoured to allure Greeks and other workmen by employing them on public works, notably in the construction of a palace—for which, Critobulus rightly says, he had chosen the most beautiful site in the city, namely, at Seraglio Point—on the construction of the fortress of the Seven Towers around the Golden Gate, and at the repairs of the Inner Wall. He ordered the Turks to allow their slaves to take part in this work, so that they might earn money not only to live but to save enough for their ransom.516

Toleration of Christianity decreed.

Mahomet’s most important step towards conciliation was to decree the toleration of Christian worship and to allow the Church to retain its organisation. As George Scholarius had been the favourite of the Greeks who had refused to accept the Union with Rome, Mahomet ordered search for him. After much difficulty, he was found at Adrianople, a slave in the house of a pasha, kept under confinement as a prisoner, but treated with distinction. His master had recognised, or had learned, that his captive was a man of exceptional talent. He was sent to the sultan, who was already well disposed towards him on account of his renown 383in philosophy. Scholarius made a favourable impression in the interview by his intelligence and manners. Mahomet ordered that he should have access to the palace when he wished, begged him always to speak freely in their intercourse, and sent him away with valuable presents.

A Record of the ecclesiastical affairs of the Orthodox Church, written within ten years after the capture, states that Mahomet, desiring to increase the number of the inhabitants of Constantinople, gave to the Christians permission to follow the customs of their Churches, and, having learned that they had no patriarch, ordered them to choose whom they would. He promised to accept their choice and that the patriarch should enjoy very nearly the same privileges as his predecessors. A local synod having been called, George Scholarius was elected, and became known as Gennadius. The sultan received him at his seraglio, and with his own hands presented him with a valuable pastoral cross of silver and gold, saying to him, ‘Be patriarch and be at peace. Count upon our friendship as long as thou desirest it, and thou shalt enjoy all the privileges of thy predecessors.’

After the interview the sultan caused him to be mounted upon a richly caparisoned horse and conducted to the Church of the Holy Apostles, which he presented to him as the church of the patriarchate as it had formerly been.518

After the election of Gennadius, the sultan, according to Critobulus, continued his intercourse with the new patriarch and discussed with him questions relating to Christianity, urging him to speak his mind freely. Mahomet even paid him visits and took with him the most learned men whom he had persuaded to be present at his court.

Later attempts to repeople capital.

During the long reign of Mahomet his attention was again and again directed to the repeopling of his capital, In addition to the attempts already mentioned, Critobulus recounts many other efforts made with the same object. But the sultan’s inducements mostly failed. The Christians mistrusted his promises, and experience showed that they were justified in so doing. Mahomet addressed himself to the Greek noble families and endeavoured to persuade them to return to the city. He publicly promised that all who came back and could prove their nobility and descent should be treated with even more distinction than had been shown to them under the emperor and should continue to enjoy the same rank as before. Relying on this promise, a number of them returned, on the feast of St. Peter. They, however, paid dearly for their credulity. Either the promise which had been given was of the hasty, spasmodic kind which has often characterised the orders of most of the Ottoman sultans and was repented of, or it had been given treacherously with no idea of its being kept. The heads of the nobles soon sullied the steps of Mahomet’s court. The repeopling which could not be done by persuasion was attempted more successfully by force.

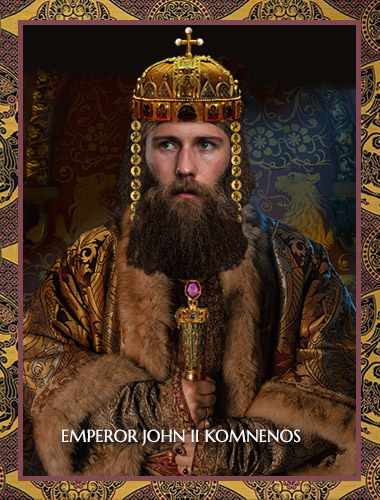

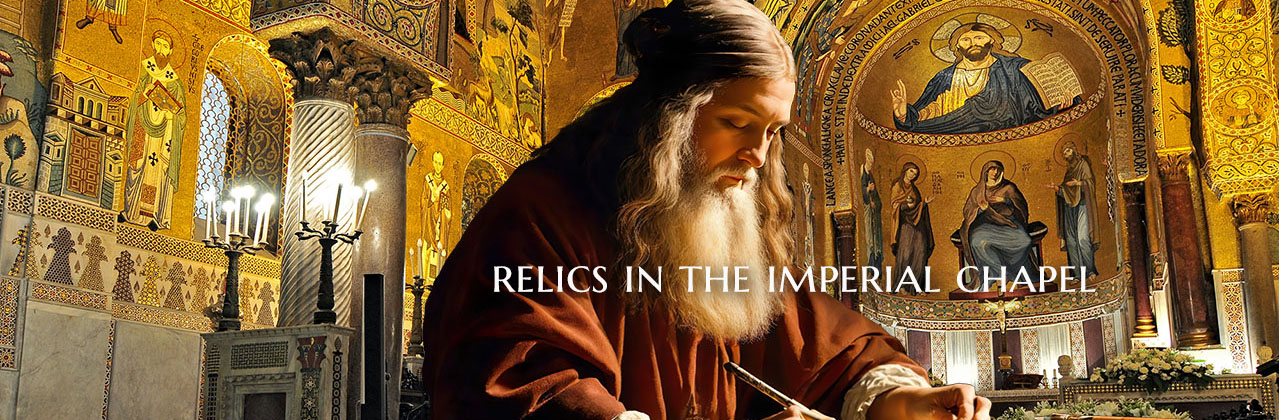

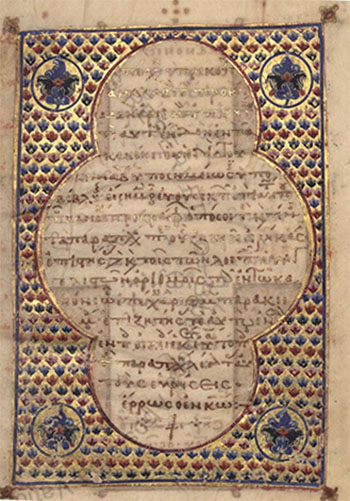

The book is small - 7.25 x 4.75 inches. The surface has been coated with a chalky white ground and the paint is laid on extra thick. It is inscribed "May this manuscript, prepared for the family of the Emperor of the Romans, continue to bless the kingdom of God," and is believed to date to 1122. It is described in the catalog of the Vatican Library as MS Urbinate Gr. 2.

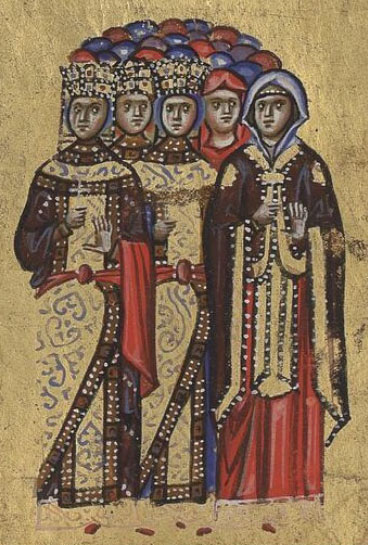

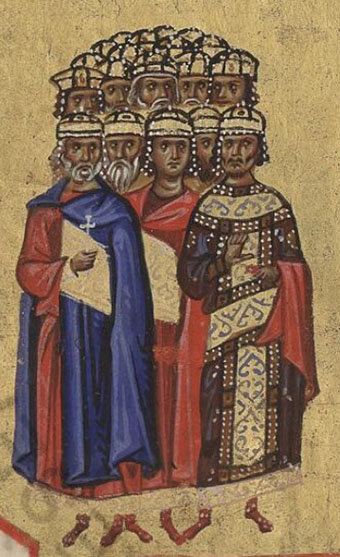

The book is small - 7.25 x 4.75 inches. The surface has been coated with a chalky white ground and the paint is laid on extra thick. It is inscribed "May this manuscript, prepared for the family of the Emperor of the Romans, continue to bless the kingdom of God," and is believed to date to 1122. It is described in the catalog of the Vatican Library as MS Urbinate Gr. 2. It possible the same workshop was involved in the design of her mosaic in the South Gallery of Hagia Sophia. It is called the family gospels because it was expressly made for John as deluxe family edition. There is a special illustration of the Nativity of John the Baptist that was included because the gospels were made for his namesake, the second emperor of the Komnenian dynasty. It's possible it was produced for his son Alexios who used it as his personal New Testament. The Gospels were in Greek, unlike the Roman Church whose gospels were in Latin and incomprehensible to the common man or women, all literate Byzantines had direct access to the Gospels.

It possible the same workshop was involved in the design of her mosaic in the South Gallery of Hagia Sophia. It is called the family gospels because it was expressly made for John as deluxe family edition. There is a special illustration of the Nativity of John the Baptist that was included because the gospels were made for his namesake, the second emperor of the Komnenian dynasty. It's possible it was produced for his son Alexios who used it as his personal New Testament. The Gospels were in Greek, unlike the Roman Church whose gospels were in Latin and incomprehensible to the common man or women, all literate Byzantines had direct access to the Gospels. John was very devout and believed he was chosen by God to serve and emperor. His primary responsibility was to protect the people of the empire and defend the church of Christ from all enemies. He took this role very seriously. The throne was a terrible responsibility and an impossible weight for any man to bear. He was assassinated - poisoned - by Crusader allies.

John was very devout and believed he was chosen by God to serve and emperor. His primary responsibility was to protect the people of the empire and defend the church of Christ from all enemies. He took this role very seriously. The throne was a terrible responsibility and an impossible weight for any man to bear. He was assassinated - poisoned - by Crusader allies. Alexios served as co-emperor with his father. Here is his portrait from Hagia Sophia. His crown is different than his father's. This mosaic and the manuscript have the same crown which was most likely made for his coronation. Alexios died before his father of some virus, his brother died of the same virus while he was taking the body of Alexios back to Constantinople to bury him in the Pantokrator Monastery. Alexios had spent most of his life on campaign with his father and traveled all over the empire. John II took his sons with him everywhere he went. This gospels went with them. As mentioned earlier, in the Renaissance the book was the prized possession of the Duke of Mantua.

Alexios served as co-emperor with his father. Here is his portrait from Hagia Sophia. His crown is different than his father's. This mosaic and the manuscript have the same crown which was most likely made for his coronation. Alexios died before his father of some virus, his brother died of the same virus while he was taking the body of Alexios back to Constantinople to bury him in the Pantokrator Monastery. Alexios had spent most of his life on campaign with his father and traveled all over the empire. John II took his sons with him everywhere he went. This gospels went with them. As mentioned earlier, in the Renaissance the book was the prized possession of the Duke of Mantua.

Eirene is described in poetry of the time as “mistress of the Muses and Muse Kalliope,” “lustrous child of Hermes,” and “sweet-singing Siren".

Eirene is described in poetry of the time as “mistress of the Muses and Muse Kalliope,” “lustrous child of Hermes,” and “sweet-singing Siren".

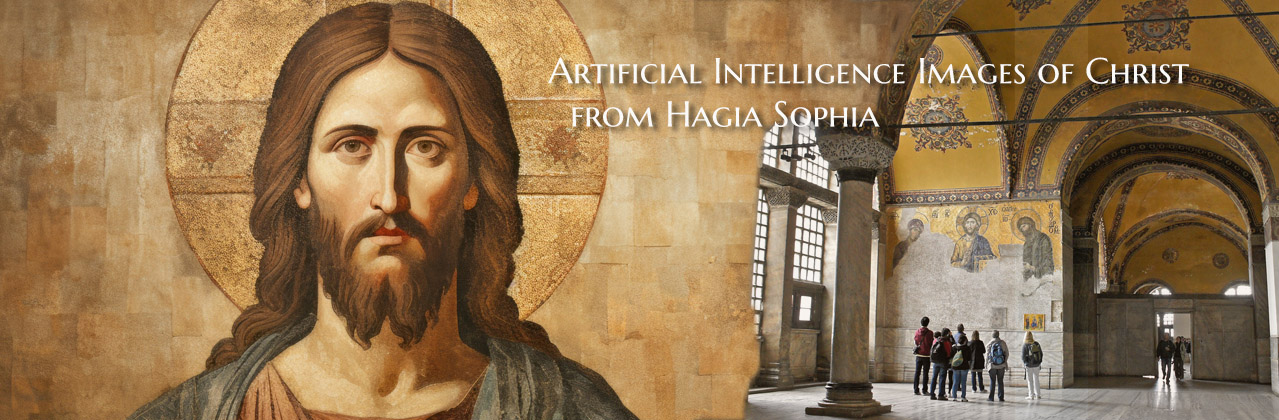

click here for icons of christ

click here for icons of christ click here for icons of the theotokos

click here for icons of the theotokos click here for icons of angels

click here for icons of angels click here for icons of saints

click here for icons of saints