Зборник радова Византолошког института LVI, 2019.

Zbornik radova Vizantološkog instituta LVI, 2019.

UDC: 7.041:271.2-526.62

726.54(495.02):271.2“11/12“

https://doi.org/10.2298/ZRVI1956233S

CHRISTINA SAVOVA

New Bulgarian University, Sofa, Bulgaria savova.christina@gmail.com

THOMAS TOMOV

New Bulgarian University, Sofa, Bulgaria pyperko@yahoo.com

This paper sheds light on the graffito-drawing from Hagia Sophia. It mainly discussed the possibility that the graffito presented a Western medieval woman donating a chalice. It is also very probable that the graffito was a work of the 15th century, produced by a anonymous skilled author, who must have been familiar with the woman’s fashion of his time.

Keywords: graffiti, drawing, medieval clothes, medieval fashion, Hagia Sophia, deaconess, medieval headdress, gown

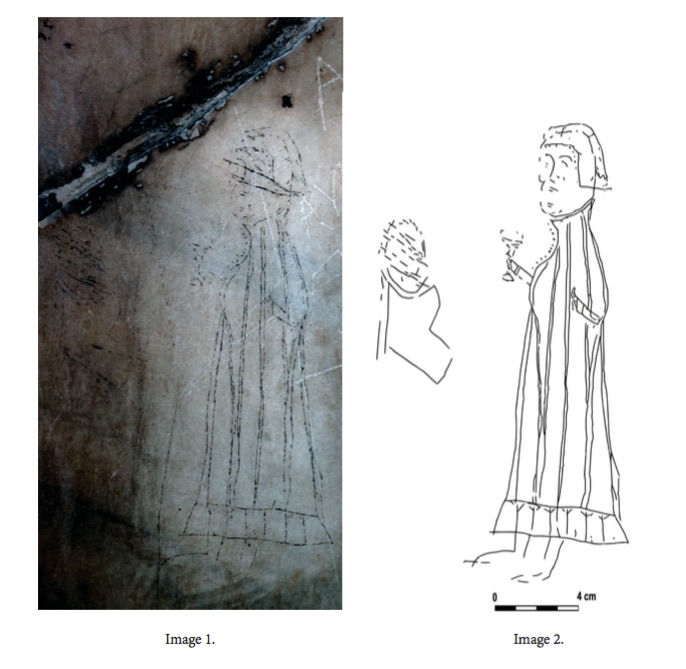

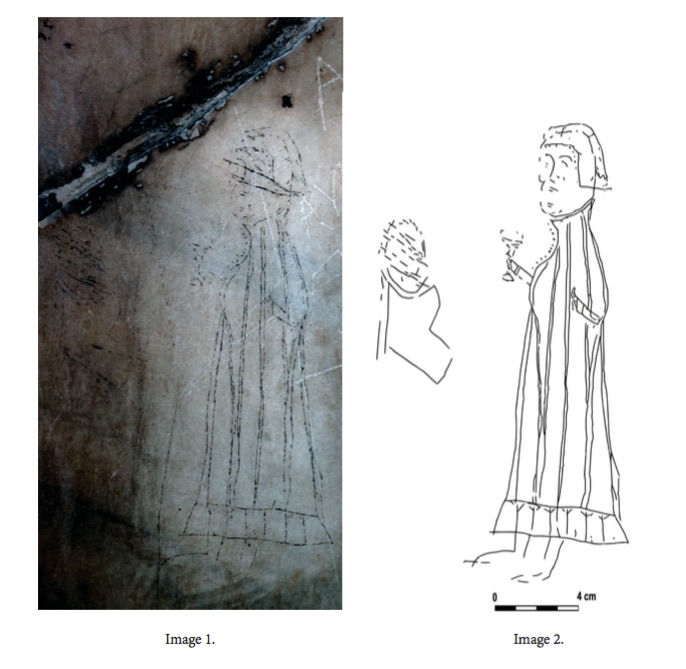

One of the places with abundance of graffiti is the Great Church or the Church of the Holy Wisdom – the famous sixth-century domed church, which was built by emperor Justinian the Great. It was considered to be one of the wonders of the world and the most important religious edifice in the city of Constantinople. Hagia Sophia was a focus of God’s blessing with tales of wonders and miracles, well-known beyond the borders of Byzantium. In the Great Church, graffiti comprised inscriptions in various languages, as well as some drawings. The marble wall plate on the right side of the last window (from left to right) on the eastern wall of the north gallery of Hagia Sophia contains a unique graffito drawing. e drawing, which is 7.5 cm in width and 23 cm in height, is lightly engraved at about 130 cm above the floor. Above the graffito two Greek monograms are inscribed. The left one can be decoded as “Meletios”, and the second one ‒ as “Patriarchos”. An inscription between them, written in Old Slavonic and dated between the second half of the 12th to the beginning of the 13th century announced the prayer for the dead woman: “O Lord, commemorate the sinful Thedora Smena”. A Greek inscription was written immediately above the Old Slavonic one. e anonymous Greek author uses some of the Cyrillic letters to create his own inscription which runs as follows: “ΔΗΑΚ[Ο]ΝΗ[ΣΑΝ]” or “deaconess”. It makes its appearance chiefly after the creation of the drawing ‒ a full-length figure of a woman with a chalice in her right hand. The main purpose of this paper is to present the graffito of the woman’s figure and to show the lack of connection between the drawing and the Old Slavonic inscription, as well with Greek word “Deaconess” due to the absence of the most marked characteristic of the deaconess: an orarion.

The anonymous author seems to have been a trained artist and a careful observer, and he captured the most essential features of the composition with great fidelity (see Image # 1 and 2). This is supported by such details as bands (stripes), ornamental decoration, cuffs, and headdress with cross. The woman’s sleeveless over-garment with standing high collar and closed in front with buttons goes down to her calves. It has slits for the arms to show that the fitted under-garment’s sleeves ended with cuffs at the wrist. Its decorative stripes ended at the ru e or lower part of the hem. This over-garment accentuated the body and made buttons and buttonholes necessary. A long row of eleven buttons started at the woman’s chest and stretched up to her chin.

She is wearing a longer under-garment reaching to the calves with modest Y-shaped ornamentation at the lower hem. She is holding a chalice with her right hand, while her left hand can be seen through the slit or side opening. Finally, a pair of shoes can be seen beneath the hem of the under tunic. Small embellishments on the collar, and sometimes the shoes emphasize the dignity of the citizen.

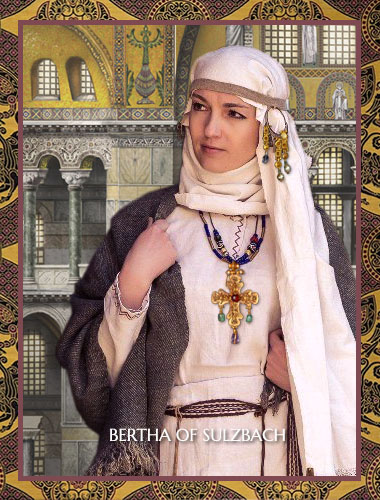

On her head she is wearing a close-fitting cloth caul or cap without ties, resembling a baby bonnet, covering the ears and identifies her as a married woman. It seems to us much more like Western medieval than anything Byzantine because the common maphorion is much longer. Definitely, the cross on the top of the headdress is more Byzantine than Latin, but this could be an example of some “cross-pollination” of dress and other practices. Perhaps the cross on the headdress is an indication that the woman was a pilgrim making an offering.

We come now to the question of the woman’s clothes. It seems much more likely that the upper-garment is a long gown known as “the houppelande” (worn by both sexes). The houppelande rst appeared about 1359 and persisted well into the 15th century. Its earlier form was similar for both men and woman. It was a voluminous upper garment tting the shoulders and generally falling in tubular folds. It has a high, bottle-neck collar, buttoned right up to the ears, and expanding round the head. Sleeves were very wide, expanding to a funnel shape below. A belt was usual but optional. e belt worn by men was at natural waist level, and by women high up under the bust. The length varied: from tailing on the ground (in ceremonial costume) to the ankle, calf, or just below the knee. In the second half of the 14th century the buttons were set to position between neck and hem, instead of from neck to waist. The front opening of the houppelande was buttoned or laced closed to the chest, or reached down to the hem. They were also fashionable accessories. At the end of the 14th century men and women styles started to diverge into distinct garments.

The feminine houppelande was longer, with a high-necked collar, sometimes with slashed sleeves, and lined or edged with fur. By the early 15th century most women, be they a lady or rich merchant’s wife, might have worn it regularly. During that time the bodice became more fitted round the shoulders and upper chest, and the fullness moved downwards to the hips, as can be seen on the drawing.

As for the garment’s ornament, the festoons were preferable decoration for the hem itself or folds, and by 1400 they decorate the openings for the sleeves. It was not unusual for the edges of the garment to be made of fur. There are also images of houppelande decorated with broad and narrow thin strips and embroidery. In Italy, the houppelande changed slightly and was named zimarra, and in Germany it became a very comfortable garment called tapert.

The discipline of the church today requires a woman to cover her head before entering a cathedral for worship. us, most of the women covered their hair with linen head cloths: caps or kerchiefs, wimples, sometime voiles or hoods but from the middle of the 14th century, the headdress became more complex. e style of headdress was ephemeral and changed regularly ‒ like fashion, and its quality and complexity was a sign of the owner’s status. e high collar of the early houppelande a ected the style of headwear: the frilled veil was replaced with a caul or small cloth cap without ties. Apparently, the cauls seem to have been worn by all levels of society or they were just an alternative to other types of headwear such as veils and hairnets. However, they would fall into the category of headwear worn by married women, the same way as veils would. In other words, a person with such an extreme high expanding collar needed only a small cap to top o his collar. It seems that in this case we are dealing with such a small cloth caul or cap covering the ears and confining the back hair.

Another possibility led us to the nun’s headdress with a small cloth cap covering the ears and a short veil on the back of the head. As an illustration of this, one may consult the manuscripts from the 14th and 15th centuries.

We also have no difficulty in believing that she must be holding a chalice in her right hand. We are skeptical about a more specific association of the vessel from the drawing with the Eucharist. A woman (even the Empress) would not touch the chalice while taking communion. is leads to assumption that the drawing depicted an act of donating. at is a Western medieval woman donating a chalice, much as the 6th century Empress Theodora is depicted in a mosaic at St. Vitale in Ravenna, donating a Eucharistic paten. A simple and more probable explanation would be that this is a Western medieval woman donating a chalice. us, we can conclude that for the person who created this drawing it was necessary to emphasize the act of donating.

In order to provide an approximate date for the drawing, it is necessary to consider some characteristic details of the clothes. Firstly, we must turn to the high-necked collar of the houppelande, which in the feminine types was into fashion up to ca. 1415. To this, we should add the fact that in the beginning of the 15th century the woman’s houppelande was diverged into a distinct garment. Because of this, it seems feasible to date the graffito with a reasonable certainty to the beginning of the 15th century. For this reason, one cannot sustain any kind of connection between the drawing and the Cyrillic inscription. Consequently it may be concluded that the Greek word ‘deaconess’ was incised a er the appearance of the drawing. However, as has been stated above, the lack of an orarium is what shows that the figure is not a deaconess.

Therefore, the graffito was a work of the 15th century, produced by an anonymous skilled author, who must have been familiar with the woman’s fashion of his time. Such an assumption, as well as the Western origin of the dress would require us to conclude that he was a Westerner. Some support for this comes from the concentration of the large number of Latin graffiti in the northern gallery of the Church of Hagia Sophia. It is apparent from their careful examination that the middle and eastern part of the gallery was a preferable area for the Westerners. Moreover, this might be the exact reason for the author’s choice of a scratching place. While this explanation is quite plausible, we do not wish to rule out the possibility that the author might be native inhabitant of the City knowing well westernizing female dress31. Unfortunately, his identification opens the door of various hypotheses. In such circumstances and with meagre evidence at our disposal it would be unwise to attempt an identification of the author of the graffito to drawing.

Download a PDF of this article with footnotes - click here.