In the 1980s the French collector Pierre de Gigord traveled to Turkey and collected thousands of Ottoman-era photographs in a variety of media and formats. The resulting Pierre de Gigord Collection is now housed in the Getty Research Institute, which recently digitized over 12,000 of the nineteenth - and early twentieth - century photographs, making them available to study and download for free online. I have assembled a collection of images of Hagia Sophia from that archive. I have cropped, improved the contrast and decreased the saturation in the darkening of a few of them which added a distracting reddish hue.

One of the first things I noticed about the images is how badly the Fossati oil painting of the vaults and walls and has decayed. Sometime in the mid to late 18th century the Ottomans whitewashed the mosaics. Whitewash breathes and it did less damage than Fossati did by plastering and then painting everything in oil paints. The oil paint created a seal that kept in moisture. Within a few years the paint pealed very badly and began to blister off and fall. The water that had backed up under and on top the plaster layer made huge chunks of mosaic fall. There was a horrible earthquake in 1894 that damaged Hagia Sophia and most likely shook down huge areas of plaster and mosaic from the vaults. This earthquake had less effect on the wall mosaics. There does not seem to be a record of the repairs that was done after the quake from 1894 - 1907. A recent survey of the dome shows that this restoration effected a large part of the mosaic there. You will be able to see the damage being done to the Fossati restoration as soon as 15 years after it was completed. the earliest image here that shows the damage is dated 1860.

Bob Atchison

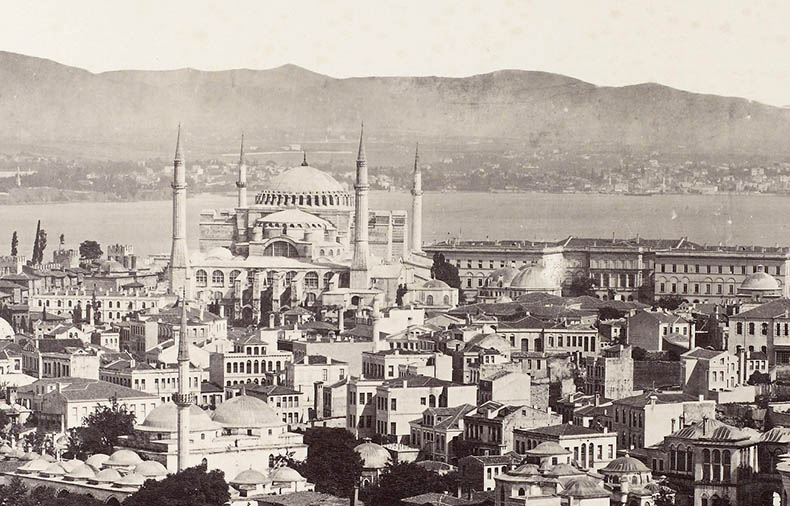

Aerial View of Hagia Sophia showing the Ottoman Palace of Justice which was built over the remains of the Great Palace. It burned down early in the 20th century.

Aerial View of Hagia Sophia showing the Ottoman Palace of Justice which was built over the remains of the Great Palace. It burned down early in the 20th century.

Hagia Sophia from the southwest. It was painted in stripes because it was through that was an appropriate Byzantine style to use. In Byzantine times Hagia Sophia was painted blue and had a gilded dome.

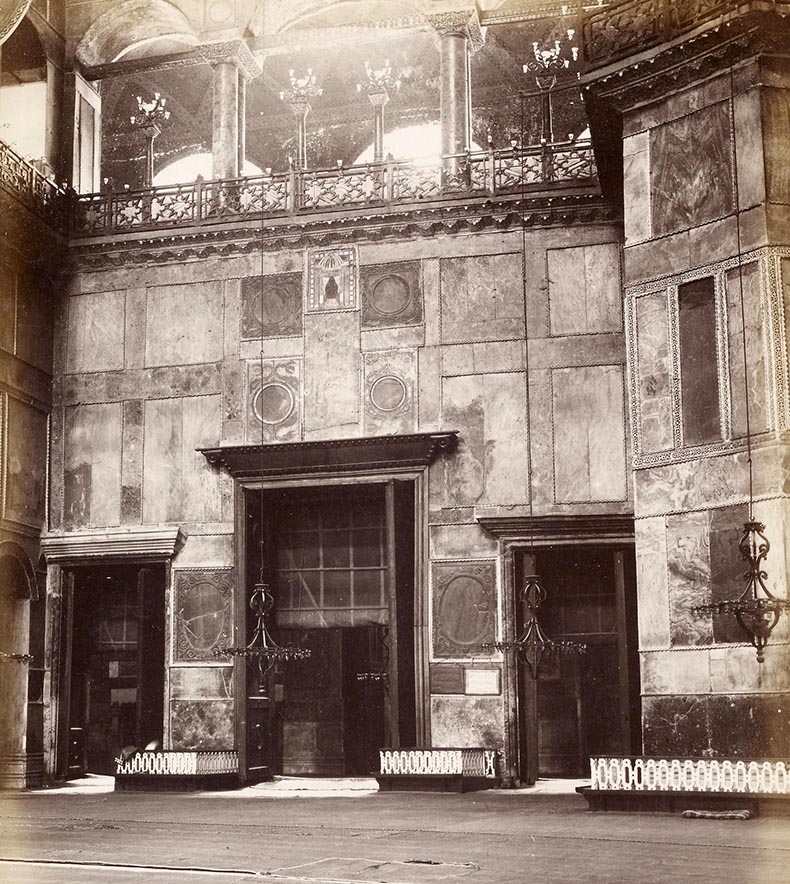

The inner Narthex looking south. The floor is covered with plain carpeting. In Ottoman times fancy rugs were brought it for special occasions. You can see huge Turkish curtains with Islamic inscriptions are hung over all of the doors. These were removed when Hagia Sophia became a museum.

This image shows the Royal Door open into the sanctuary. The curtain can be lowered up and down so the great doors (which were claimed to be made of wood from Noah's Ark) don't have to be open and closed constantly. In Byzantine times these doors were covered in sheets of silver inlaid with gold and their were two famous icons here, hanging on either side of the door. You can see the threshold, made of Verde Antique marble, has been worn down by centuries of traffic. It had already been replaced at least once at some point.

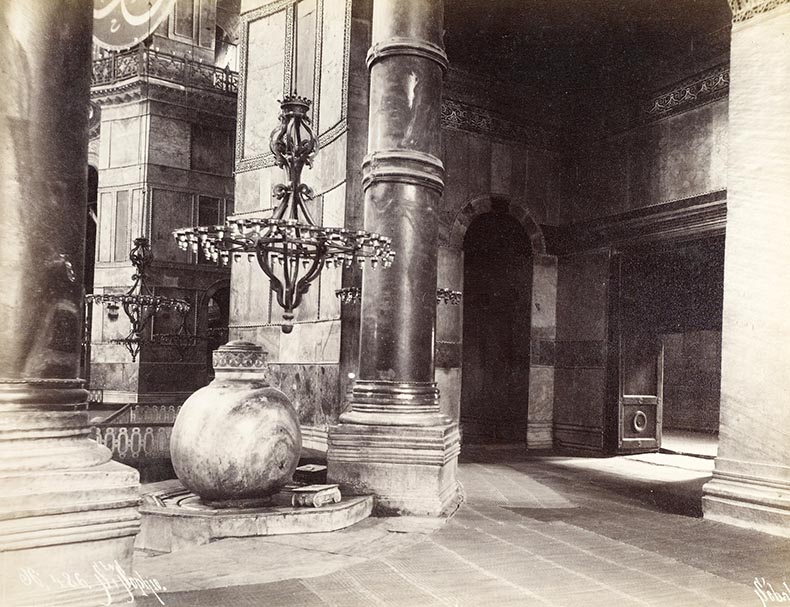

Here is a view of the southern side of the nave showing the monolithic columns of green Verde Antique marble from Thessaly in Greece. They were newly quarried for the construction of Hagia Sophia. The story that these came from the Temple of Diana at Ephesus is a myth.

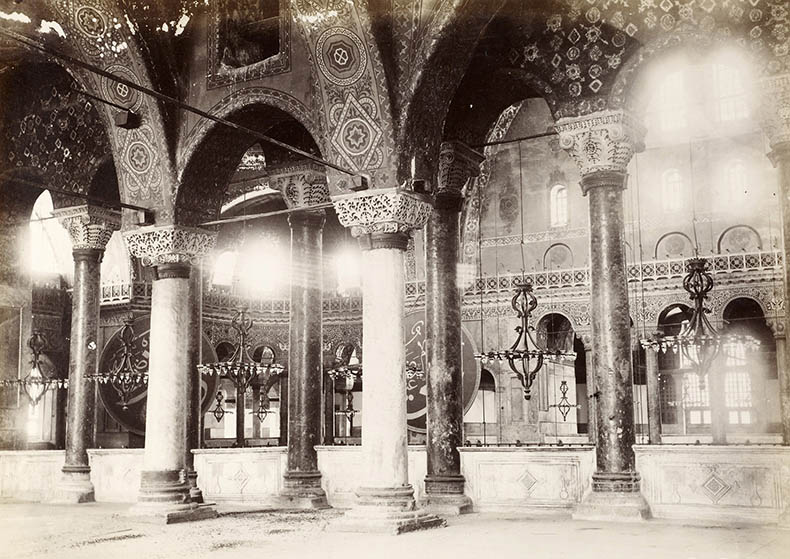

This is a view of the opposite, northern side of the nave. You can see the Sultans Box in the distance. The chandeliers are Ottoman and made of wood. They hold glass inserts for the burning of oil lamps. Today these have been electrified and are covered with ugly electric wiring. In Byzantine times the chandeliers were smaller and made of silver. Each one of them held 6-12 oil lamps.

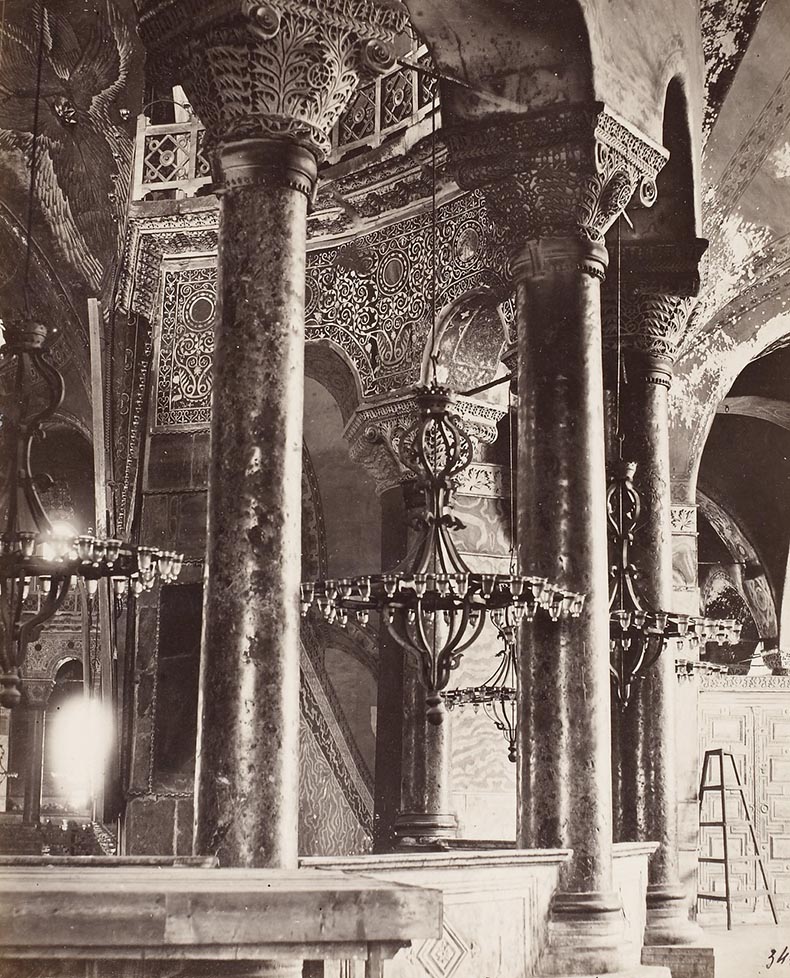

The Sultan's Box was added in the mid 19th century during the Fossatti restoration. It replaced a very small one. One cannot argue with the fact that it is really beautiful. It stands on delicate columns made of Dokimeion Pavonazzetto marble, from Iscehisar (Synnada), in Afyonkarahisar province, Turkey. They are white with spidery red veining. These columns were reused, the quarry stopped production in the 7th century. In the 19th century there were still many blocks and unfinished column shafts left in the quarry.

This is a view of the west wall of the nave. You can see how the cross and doves in the inlaid panel have been plastered over with black paint so you can't see them. Just below that panel, where the huge panel of Verde Antique is, was the location of a famous Byzantine mosaic icon of a standing Christ Chalkites, the original hung over the door of the entrance to the Great Palace, called Chalke. It was destroyed during Ottoman times. The panels on either side of the mosaic have inlaid dolphins swimming around disks of Red Porphyry. Orphans stood on benches to the left of the Royal Doors and shouted best wishes and prayers for the emperor when he passed here.

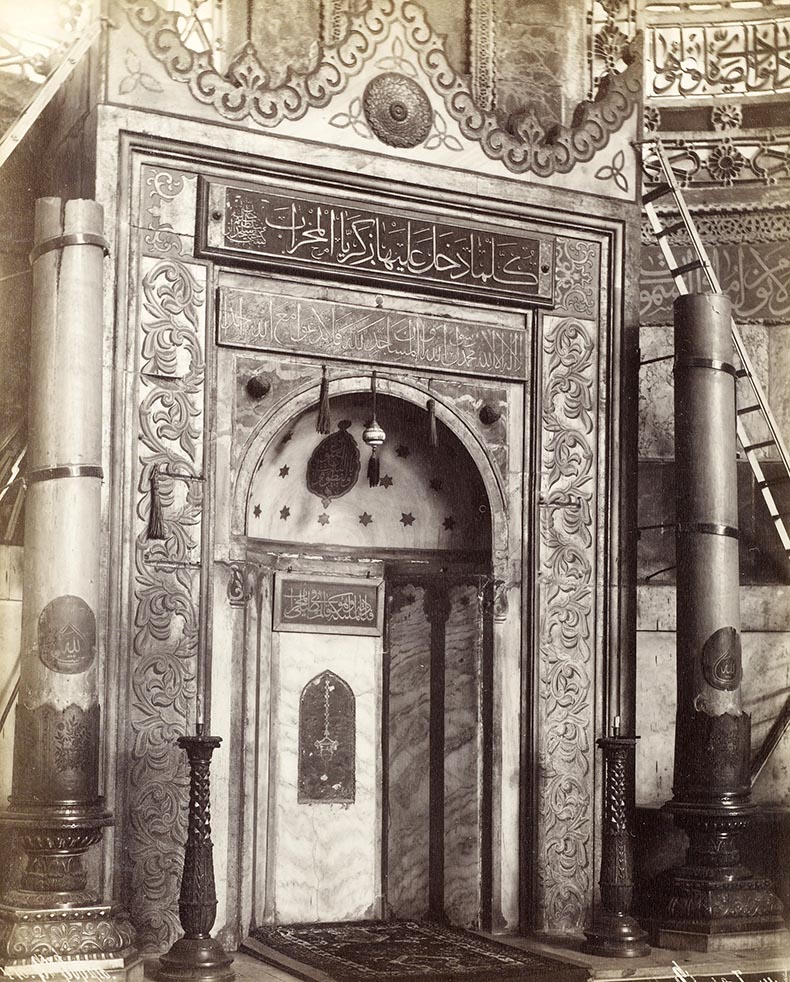

The Muslim Mithrab. It was added after the conquest to indicate the direction of Mecca for prayers. It replaced a great curved, multi-tiered marble bench that was placed against the back of apse for Christian clergy to sit on during services. There was a passage they ran underneath it.

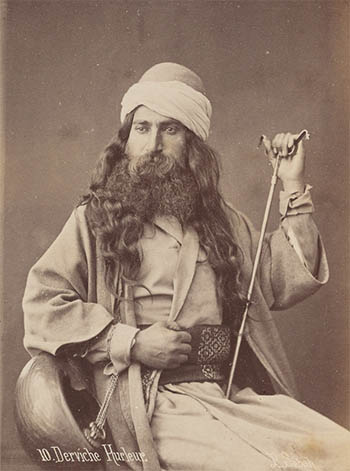

This is the Ottoman minbar, Muslim preachers used it. In Byzantine times there was a huge columned Ambo in the center of the nave where sermons were delivered from. Choristers stood underneath and around the Ambo chanting prayers and hymns. Hagia Sophia has a 10 second echo, which made it difficult to hear the spoken word. In response the Byzantines invented a beautiful sung liturgy that was specifically designed to be more easily heard and followed.

Here are two Red Porphyry columns from Hagia Sophia in the southwestern exhedra. Porfido rosso antico the ancient name for Red Porphyry were quarried by slaves at Gebel Dokhan (the ancient Mons Porphyrites) in the Eastern Desert of Egypt. The quarries stopped production in the 5th century and these columns were reused or came from existing stock. They vary in size up to 28 feet tall, and the bases are of different heights to fit the column.

The columns are set into soft lead blanks at their bases. This prevents earthquake damage. I have read that the columns are not all monoliths, but have been assembled in pieces and that some of the collars mark these joints. One is fractured. The stone is extremely hard and difficult to fashion into columns. It is also brittle, splits and flakes. You can see how bronze (or lead) collars have been added to stop them from cracking under the immense weight they carry. These collars were added very early in the history of the church. We don't know how they came to Constantinople or where they brought from. They could have come from Rome at the time of Constantine or have been brought from some capital during the Tetrarchy, like Nicomedia, the modern Izmit, not very far from Constantinople.

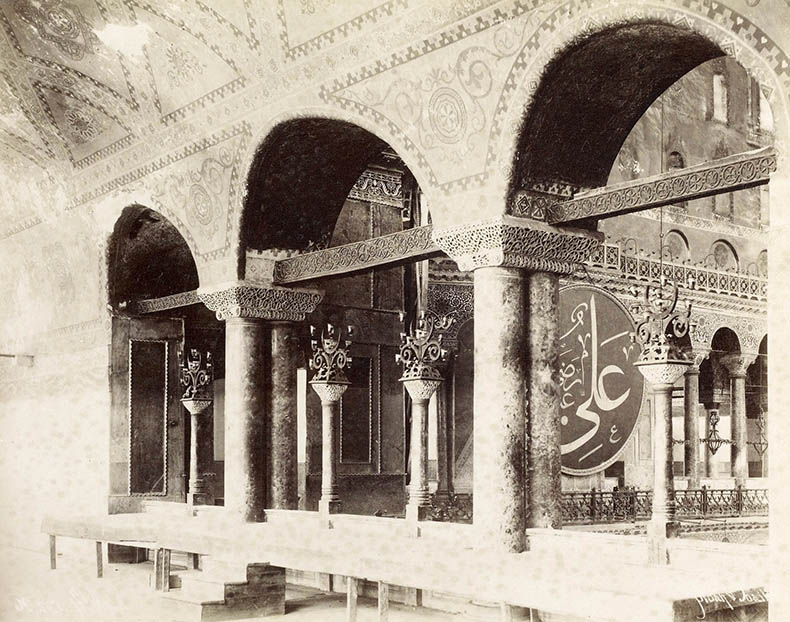

The West Gallery of Hagia Sophia, which is the size of a cathedral. There are no carpets on the Proconnesian marble floors. I am not sure what was in those wooden boxes, perhaps they were Korans. The platform in front of the arcade would allow you to prostrate yourself and pray in the Muslim manner. In Byzantine times the ceiling was covered in gold mosaic set with a multi-colored geometric pattern in glass mosaic similar to the pattern we see painted in oils here.

Another view of the West Gallery. The arcade has columns in green Verde Antique marble, while the capitals are carved in white Proconnesian marble. The carved wooden tie beams are the originals from the 6th century. The original candelabra, also in Verde Antique, have bronze arms set with glass oil lamps. There are low parapet panels in white marble bearing crosses which have been obliterated. The Byzantine Empress used to sit here during services and special ceremonies.

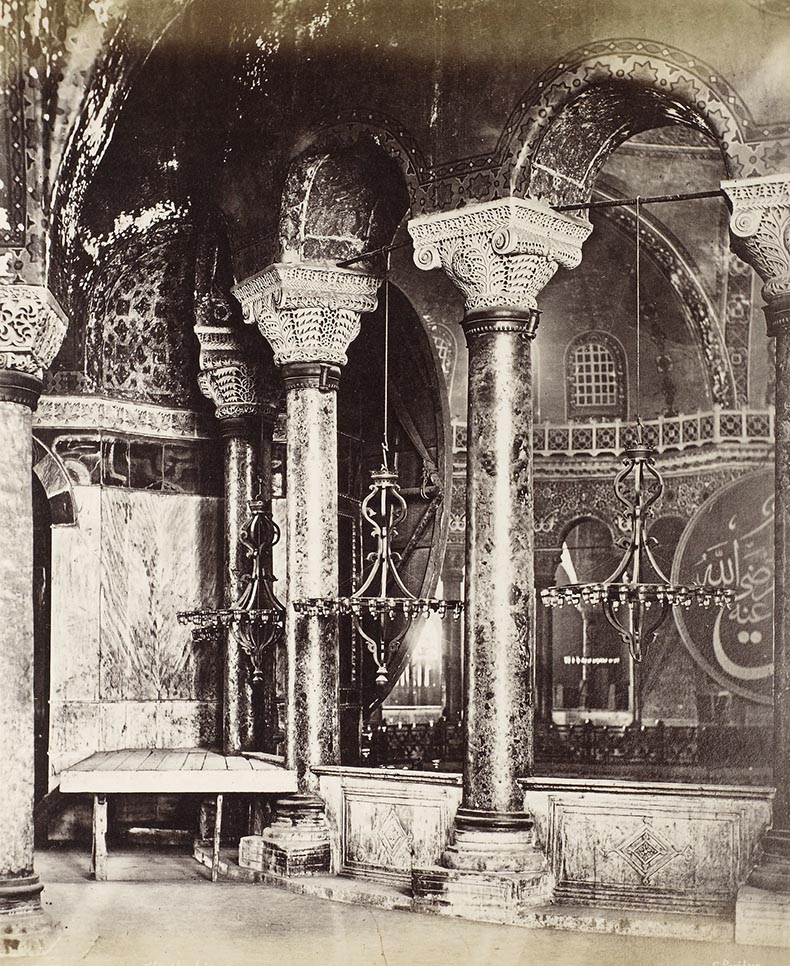

View into the nave from the central bay of the South Gallery. Here you can see more white marble panels with their erased crosses.

Further east this image from the South Gallery shows the southeast exhedra Here is another Muslim prayer platform. This is the closest part of the South Gallery to the sanctuary, in Byzantine times it was used by the Imperial family and also by the church for meetings. The vaults here were originally covered by huge red-winged Seraphim and Cherubim set in gold mosaic. There was an image of Christ Pantokrator in the dome. Prior to the mid 18th century these mosaics were never covered up. For three hundred years Muslim worshipers prayed under them.

The white columns are Proconnesian marble while the colored ones are green Verde Antique.

Another view of an exhedra in the galleries.

Here is the back southeast entrance to Hagia Sophia, which dates from Byzantine times. Above it you can see the famous door to the South Gallery, which now opens into open air. In Byzantine times there was a wooden staircase attached to it which led to a passageway that took you to the Great Palace. The emperor went up and down this staircase when he moved back and forth from the nave to the South Gallery. The Byzantine Imperial family used the suspended walkway, which was also connected to the Chalke Gate, to enter the church privately. The door is next to the mosaic of John II Comnenus and Augusta Eirene. There are still writings on the interior walls here - on either side of the door, left by people who walked here, including an assistant to a Patriarch named Philip who left his name and a prayer scratched into the marble doorway in Slavonic.

click here for icons of christ

click here for icons of christ click here for icons of the theotokos

click here for icons of the theotokos click here for icons of angels

click here for icons of angels click here for icons of saints

click here for icons of saints