By Ignatius of Smolensk

Ignatius was an eyewitness, but he left out many important details which I have added in using blue italic text from another account that was in Byzantinishe Zeitscrift 60 published in 1967. Manuel had married his wife the day before.

At the bottom of the page are some things related to the visit of Manuel to Henry IV and London 1400-1401.

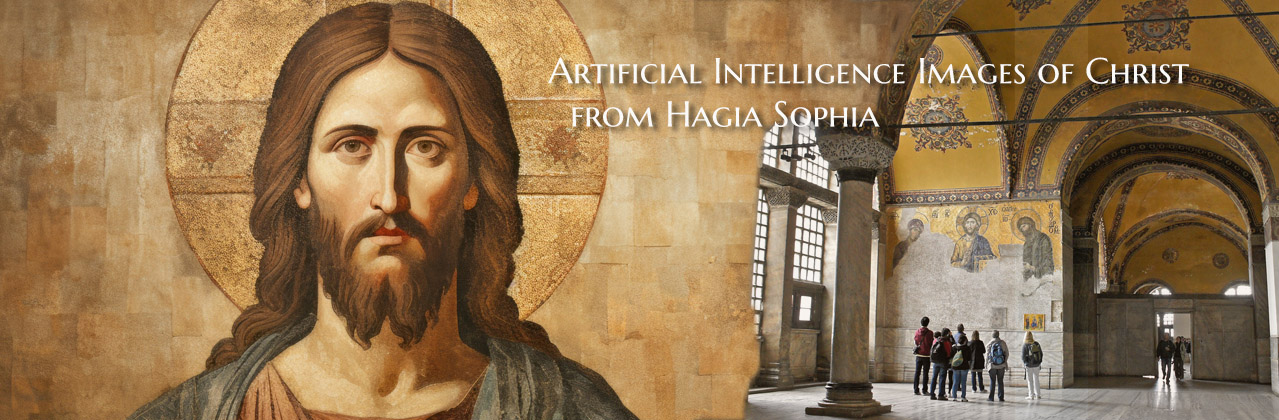

The Turks paid Manuel the ultimate compliment, saying he resembled the Prophet Mohammed. From contemporaries we know he had an aquiline nose, fair skin and long white hair and beard; and he was well-built, strong and agile. He had blue eyes.

Bob Atchison

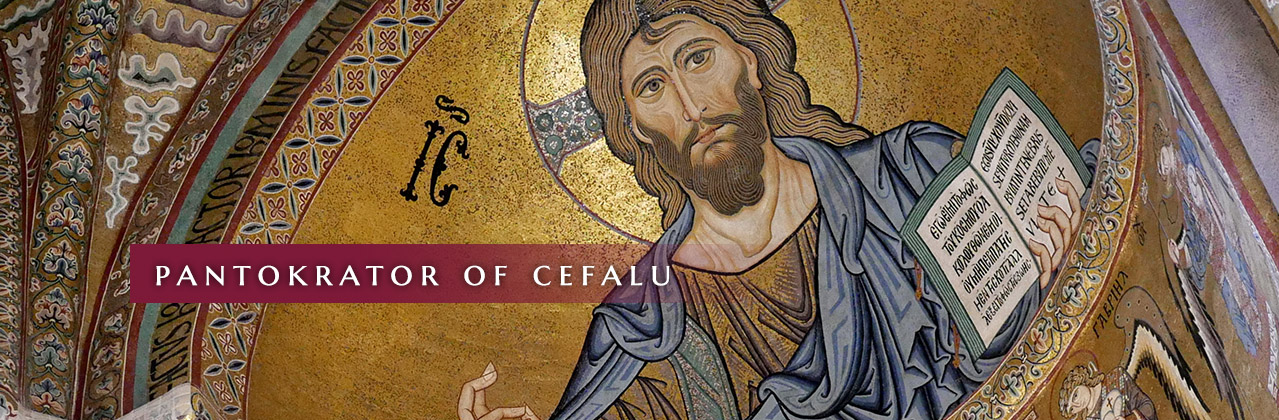

In the year 6900 (1392) on the eleventh day of the month of February, on the Sunday of the Prodigal Son, Manuel was crowned emperor over the empire with his wife the empress by the holy Patriarch Anthony, and his coronation was wonderous to see. That night and All-night Vigil Service was held in St. Sophia. I went at daybreak so I was there for the coronation. A multitude of people were there, the men inside the holy church, the women in the galleries. The arrangement was very artful; all those who were of the female sex stood behind silken drapes so that none of the male congregation could see the adornment of their faces, while they could see everything that was to be seen. The singers stood robed in marvelous vestments, they had long, wide robes like sticharia, but all belted, and the sleeves of the robes were also long and wide. Some robes were of brocade, others of silk, with gold and braid on their shoulders. On their heads the singers wore pointed hats with braid. A multitude of them had gathered; and their leader was a handsome man with robes white as snow. Present were the Franks from Galata and others from Constantinople, Genoese and Venetians. Their arrangement was wonderous to see, for they stood in two groups, some wearing velvet robes, others cerise velvet. One group wore it's emblems on the chest in pearls, and the other had its on emblems, which all matched. Under the galleries on the right-hand side was a chamber and twelve steps two sazhens (9 ft) wide all covered with red stuff. On this were two gold thrones. (George Majeska has noted that this specially built wooden chamber would have fitted quite nicely on the giant central medallion of granite to the right of the ambo).

In the year 6900 (1392) on the eleventh day of the month of February, on the Sunday of the Prodigal Son, Manuel was crowned emperor over the empire with his wife the empress by the holy Patriarch Anthony, and his coronation was wonderous to see. That night and All-night Vigil Service was held in St. Sophia. I went at daybreak so I was there for the coronation. A multitude of people were there, the men inside the holy church, the women in the galleries. The arrangement was very artful; all those who were of the female sex stood behind silken drapes so that none of the male congregation could see the adornment of their faces, while they could see everything that was to be seen. The singers stood robed in marvelous vestments, they had long, wide robes like sticharia, but all belted, and the sleeves of the robes were also long and wide. Some robes were of brocade, others of silk, with gold and braid on their shoulders. On their heads the singers wore pointed hats with braid. A multitude of them had gathered; and their leader was a handsome man with robes white as snow. Present were the Franks from Galata and others from Constantinople, Genoese and Venetians. Their arrangement was wonderous to see, for they stood in two groups, some wearing velvet robes, others cerise velvet. One group wore it's emblems on the chest in pearls, and the other had its on emblems, which all matched. Under the galleries on the right-hand side was a chamber and twelve steps two sazhens (9 ft) wide all covered with red stuff. On this were two gold thrones. (George Majeska has noted that this specially built wooden chamber would have fitted quite nicely on the giant central medallion of granite to the right of the ambo).

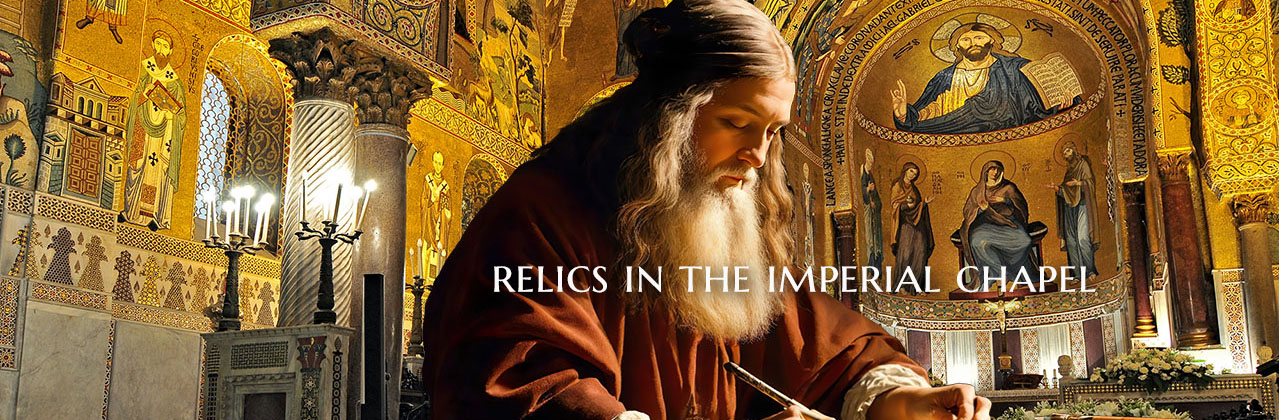

That night (the previous night) the emperor had been in the galleries, but then the first hour of the day began, the emperor descended from the galleries and entered the holy church through the main doors that are called "imperial", while the singers chanted, indescribable, unusual music. The imperial procession was very slow-paced, so that three hours were consumed going from the main doors to the chamber. Twelve men-at-arms (Varangian Guard) walked on either side of the emperor, all in mail from head to foot, in in front of them walked two black-haired standard bearers with red staffs, clothing and hats. Heralds with silver-covered staffs walked before the two standard-bearers. When the emperor had entered the chamber he donned the purple (sakkos - a real late Byzantine Imperial sakkos is shown on the left) and the diadem (in this period the diadem is type of necklace), and placed on his brow the Caesar's crown with crenellations (a bishop then handed the crown to the prokathemenos tou vestiariou - the one in charge of the wardrobe). Then leaving the chamber he went up to escort the empress to the throne. After they had set down on the thrones the liturgy began, with both the emperor and empress seated.

That night (the previous night) the emperor had been in the galleries, but then the first hour of the day began, the emperor descended from the galleries and entered the holy church through the main doors that are called "imperial", while the singers chanted, indescribable, unusual music. The imperial procession was very slow-paced, so that three hours were consumed going from the main doors to the chamber. Twelve men-at-arms (Varangian Guard) walked on either side of the emperor, all in mail from head to foot, in in front of them walked two black-haired standard bearers with red staffs, clothing and hats. Heralds with silver-covered staffs walked before the two standard-bearers. When the emperor had entered the chamber he donned the purple (sakkos - a real late Byzantine Imperial sakkos is shown on the left) and the diadem (in this period the diadem is type of necklace), and placed on his brow the Caesar's crown with crenellations (a bishop then handed the crown to the prokathemenos tou vestiariou - the one in charge of the wardrobe). Then leaving the chamber he went up to escort the empress to the throne. After they had set down on the thrones the liturgy began, with both the emperor and empress seated.

When the procession was about to begin, the two chief deacons approached the emperor and bowed to the waist. The emperor rose and went to the sanctuary, with the standard-bearers going before him and the men-at-arms on either side of him. The emperor entered the sanctuary, while the standard-bearers and men-at-arms stood in front of the sanctuary, on either side of the holy doors. The emperor was vested in a short little purple phelonian reaching to the waist, and so vested the emperor walked in procession carrying a candle in his hand. As the patriarch completed the procession, he went into the ambo with the emperor, and the crown of the emperor was brought on a covered tray, as was that of the empress. After the two chief deacons had gone to the empress and bowed, the empress also went to the ambo. The patriarch (before placing the crown on Manuel's head the Patriarch anointed him with nard and covered his head with a hood) placed the crown on the emperor, and placed a cross in his (right hand). (Here the people hail the emperor and wish him "many years") The emperor then stepped down and placed a crown on the empress (and a gold scepter ornamented with gems and pearls in her right hand). They returned to their places and sat on their thrones, while the patriarch completed the procession and what follows it.

(And the patriarch. after entering the sanctuary, sat on his throne, and one of the deacons who was standing by the doors of the sanctuary voiced the acclamation of the emperors and patriarch. And all of the people, as was the custom, hailed them with song. Behind the ambo were two platforms constructed of wood, one on the right, the other on the left. Upon them sat the maistores - important court officials guiding the ceremonies along with the choir. wearing above their clothing outer garments of gold material issued by the imperial wardrobe. For such is their function. The chief chanter and the domestikos stood motionless before the throne while the torchberarer with a double lamp stood before the emperor below the imperial platform.... a loud voice directed the singing of this verse.

Many years to you, Emperors of the Romans.

Many years, Manuel, Emperor of the Romans.

Many your years, Helen, Empress of the Romans.

For the glory and prosperity of the Romans, this is indeed is the Lord's great day

Glory, glory, glory in the highest to God and peace on earth and goodwill toward men.

Glory to God, who has crowned you rulers of the Romans.

And then they began, "many years, Emperors of the Romans" and in turn the other verses just mentioned. And they chanted them so that the beginning extended from the opening of the Holy Liturgy to its conclusion. But at the time of the coronation, the reading from the Apostle and he Holy Gospels, the Great Entrance when the Holy Eucharist was taken to the altar, the Holy Symbol, Eucharist - the prayer, Our Father and the Elevation of the Eucharist, they remained quiet. And again they began to chant:

Many, many years up to many,

Many years to many,

Many years to many,

Many years to many.)

When it was time for the Cherubic Hymn, the two chief deacons went and bowed to the emperor as they had done previously. The emperor rose and went into the sanctuary where he was vested in the small phelonion (they dressed the emperor in a gold garment in the manner of a bishop and placed in his right hand a staff). Carrying a lighted candle in his hand, he proceeded the holy oblations during their transferal. Who can express the beauty of this moment? The singing of the Cherubic Hymn continued as long as the procession of the holy oblations lasted. Then, standing at the altar, the emperor censed while the holy oblations were brought into the sanctuary. He remained in the sanctuary until the time for holy communion.

When it was time for holy communion, the two chief deacons went and bowed to the empress. When she had descended from her throne, the people standing there tore apart all the drapes on the chamber, each wanting as large a piece as possible for himself. The empress entered a wing of the sanctuary by the south doors, and was given holy communion there. The emperor, however, received communion from the patriarch at the altar of Christ together with the priests (he took holy communion with his own hand).

As the emperor left the church he was showered with staurata (a small silver coin with a cross) which all the people tried to grab with their hands.

(After the end of the service the emperor, riding on horseback, made his way from the church to the Great Palace. And the highest officials, that is, the despots, sebastokrators and caesars, led the horses of the emperor and empress by the bridal from the church to the palace.

Lament for a Beleaguered Emperor

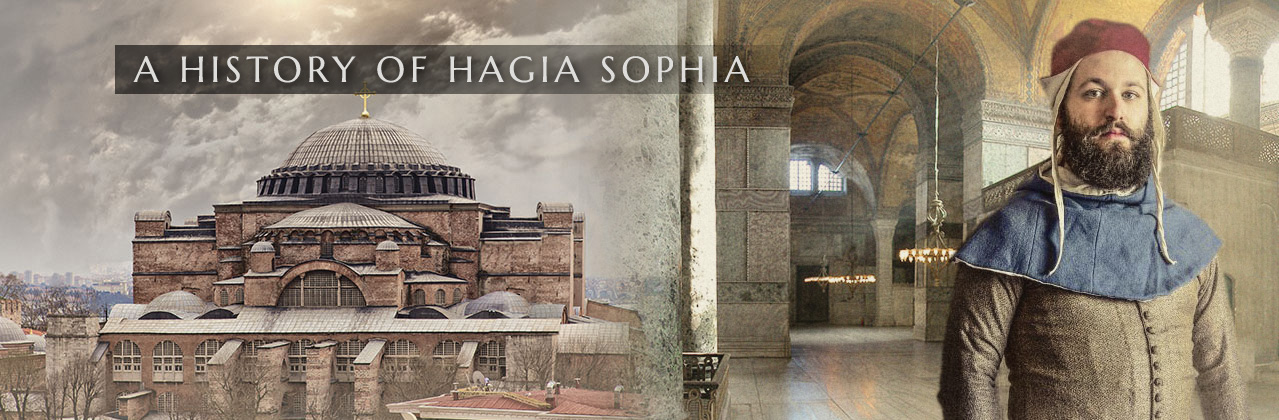

Written by the English chronicler, Adam Usk, describing the impression made by Manuel II during his visit to London in 1400. Manuel stayed for a year with Henry IV staying in Eltham Palace. He traveled with a suite of 40.

The emperor of the Greeks, seeking to get aid against the Saracens, visited the king of England in London, on the day of St. Thomas the Apostle (21st December), being well received by him, and abiding with him, at very great cost, for two months, being also comforted at his departure with very great gifts. The emperor always walked with his men, dressed alike and in one color, namely white, in long robes like tabards: he finding fault with the many fashions and distinctions in dress of the English, wherein he said that fickleness and changeable temper was betokened. No razor touched head or beard of his chaplains.

The emperor of the Greeks, seeking to get aid against the Saracens, visited the king of England in London, on the day of St. Thomas the Apostle (21st December), being well received by him, and abiding with him, at very great cost, for two months, being also comforted at his departure with very great gifts. The emperor always walked with his men, dressed alike and in one color, namely white, in long robes like tabards: he finding fault with the many fashions and distinctions in dress of the English, wherein he said that fickleness and changeable temper was betokened. No razor touched head or beard of his chaplains.

The Greeks were most devout in their church services, which were joined in as well by soldiers and priests, for they chanted them without distinction in their native tongue. I thought within myself, what a grievous thing that it was this great Christian prince from the father east should perforce be driven my unbelievers to visit the distant lands of the west, to seek aid against them.

My God! What dost thou, ancient glory of Rome? Shorn is the greatness of thine empire this day; and truly may the words of Jeremiah be spoken unto thee: "Princess among the provinces, how is she become tributary?" Who would ever believe that thou shouldst sink to such depth of misery, that although once seated on the throne of majesty thou didst lord over all the world. now thou has no power to bring succour to the Christian faith.

A letter of Manuel II from London to Manuel Chrysoloras

January-February 1401

...For what is the reason of the present letter? A large number of letters have come to us from all over bearing excellent and wonderful promises, but most important is the ruler with whom we are now staying, the king of Great Britain the Great, of a second civilized world, which you might say, who abounds in so many good qualities and is adorned with all sorts of virtues. His reputation earns him the admiration of people who have met him, while for those who have not seen him, he proves brilliantly that Fame is not really a goddess, since she is unable to show the man to be as great as does actual experience.

This ruler is most illustrious because of his position, most illustrious because of his intelligence; his might amazes everyone, and his understanding wins him friends; he extends his hand to all and in every way he places himself at the service of those who need help. And now, in accord with his nature, he had made himself a virtual haven for us in the midst of a twofold tempest, that of season and that of fortune, and we have found a refuge in the man himself and his character. His conversation is quite charming; he pleases us in every way; he honors us to the greatest extent and loves us no less. Although he had gone to extremes in all he has done for us, he seems to blush in the belief - and this he is alone - that he might have fallen considerably short of what he has done. This is how magnanimous the man is.

Now, if the rules of letter-writing require conciseness, let us say this. This man is good at what he begins, and he is good at completing the course, becoming better each day, struggling at times to outdo himself in what concerns us. In the end he has given even great proof of his nobility by adding a corning touch to our negotiations, worthy of his character and of the negotiations themselves. For he is providing us with the military assistance, with soldiers, archers, money, and ships to transport the army where it is needed.

During his stay in Britain the suite of Manuel II conducted daily liturgy. It was open to all and curious English attended. They were impressed by a number of things. First the Emperor - and his entire delegation, including soldiers - took communion; second everyone participated in the liturgy - singing and reciting it in Greek, understanding everything. This not true in their own country where the mass was in Latin, a foreign language that cut off the common people from fully participating or understanding the practice of their religion. At the time their was great turmoil in the English church created by the Lollards who wanted their church to use common English, rather than Latin. They were also surprised to discover that the Greeks could read the New Testament in their own language. The Lollards came to believe the the Byzantine Church preserved the true faith of the apostles and this became the established opinion of early Protestant theologians.

The Byzantines were pleasantly surprised to find the British were sincerely interested in their culture and the danger it was in from Islam. In Manuel's letter he refers to Great Britain the Great; in the short time they were there they fell in love with the country and its people. They always called the country Britain in Greek.

“Show me just what Muhammed brought that was new and there you will find things only evil and inhuman, such as his command to spread by the sword the faith he preached.”

“Show me just what Muhammed brought that was new and there you will find things only evil and inhuman, such as his command to spread by the sword the faith he preached.”

In the year 6900 (1392) on the eleventh day of the month of February, on the Sunday of the Prodigal Son, Manuel was crowned emperor over the empire with his wife the empress by the holy Patriarch Anthony, and his coronation was wonderous to see. That night and All-night Vigil Service was held in St. Sophia. I went at daybreak so I was there for the coronation. A multitude of people were there, the men inside the holy church, the women in the galleries. The arrangement was very artful; all those who were of the female sex stood behind silken drapes so that none of the male congregation could see the adornment of their faces, while they could see everything that was to be seen. The singers stood robed in marvelous vestments, they had long, wide robes like sticharia, but all belted, and the sleeves of the robes were also long and wide. Some robes were of brocade, others of silk, with gold and braid on their shoulders. On their heads the singers wore pointed hats with braid. A multitude of them had gathered; and their leader was a handsome man with robes white as snow. Present were the Franks from Galata and others from Constantinople, Genoese and Venetians. Their arrangement was wonderous to see, for they stood in two groups, some wearing velvet robes, others cerise velvet. One group wore it's emblems on the chest in pearls, and the other had its on emblems, which all matched. Under the galleries on the right-hand side was a chamber and twelve steps two sazhens (9 ft) wide all covered with red stuff. On this were two gold thrones. (George Majeska has noted that this specially built wooden chamber would have fitted quite nicely on the giant central medallion of granite to the right of the ambo).

In the year 6900 (1392) on the eleventh day of the month of February, on the Sunday of the Prodigal Son, Manuel was crowned emperor over the empire with his wife the empress by the holy Patriarch Anthony, and his coronation was wonderous to see. That night and All-night Vigil Service was held in St. Sophia. I went at daybreak so I was there for the coronation. A multitude of people were there, the men inside the holy church, the women in the galleries. The arrangement was very artful; all those who were of the female sex stood behind silken drapes so that none of the male congregation could see the adornment of their faces, while they could see everything that was to be seen. The singers stood robed in marvelous vestments, they had long, wide robes like sticharia, but all belted, and the sleeves of the robes were also long and wide. Some robes were of brocade, others of silk, with gold and braid on their shoulders. On their heads the singers wore pointed hats with braid. A multitude of them had gathered; and their leader was a handsome man with robes white as snow. Present were the Franks from Galata and others from Constantinople, Genoese and Venetians. Their arrangement was wonderous to see, for they stood in two groups, some wearing velvet robes, others cerise velvet. One group wore it's emblems on the chest in pearls, and the other had its on emblems, which all matched. Under the galleries on the right-hand side was a chamber and twelve steps two sazhens (9 ft) wide all covered with red stuff. On this were two gold thrones. (George Majeska has noted that this specially built wooden chamber would have fitted quite nicely on the giant central medallion of granite to the right of the ambo). That night (the previous night) the emperor had been in the galleries, but then the first hour of the day began, the emperor descended from the galleries and entered the holy church through the main doors that are called "imperial", while the singers chanted, indescribable, unusual music. The imperial procession was very slow-paced, so that three hours were consumed going from the main doors to the chamber. Twelve men-at-arms (Varangian Guard) walked on either side of the emperor, all in mail from head to foot, in in front of them walked two black-haired standard bearers with red staffs, clothing and hats. Heralds with silver-covered staffs walked before the two standard-bearers. When the emperor had entered the chamber he donned the purple (sakkos - a real late Byzantine Imperial sakkos is shown on the left) and the diadem (in this period the diadem is type of necklace), and placed on his brow the Caesar's crown with crenellations

That night (the previous night) the emperor had been in the galleries, but then the first hour of the day began, the emperor descended from the galleries and entered the holy church through the main doors that are called "imperial", while the singers chanted, indescribable, unusual music. The imperial procession was very slow-paced, so that three hours were consumed going from the main doors to the chamber. Twelve men-at-arms (Varangian Guard) walked on either side of the emperor, all in mail from head to foot, in in front of them walked two black-haired standard bearers with red staffs, clothing and hats. Heralds with silver-covered staffs walked before the two standard-bearers. When the emperor had entered the chamber he donned the purple (sakkos - a real late Byzantine Imperial sakkos is shown on the left) and the diadem (in this period the diadem is type of necklace), and placed on his brow the Caesar's crown with crenellations

The emperor of the Greeks, seeking to get aid against the Saracens, visited the king of England in London, on the day of St. Thomas the Apostle (21st December), being well received by him, and abiding with him, at very great cost, for two months, being also comforted at his departure with very great gifts. The emperor always walked with his men, dressed alike and in one color, namely white, in long robes like tabards: he finding fault with the many fashions and distinctions in dress of the English, wherein he said that fickleness and changeable temper was betokened. No razor touched head or beard of his chaplains.

The emperor of the Greeks, seeking to get aid against the Saracens, visited the king of England in London, on the day of St. Thomas the Apostle (21st December), being well received by him, and abiding with him, at very great cost, for two months, being also comforted at his departure with very great gifts. The emperor always walked with his men, dressed alike and in one color, namely white, in long robes like tabards: he finding fault with the many fashions and distinctions in dress of the English, wherein he said that fickleness and changeable temper was betokened. No razor touched head or beard of his chaplains.

click here for icons of christ

click here for icons of christ click here for icons of the theotokos

click here for icons of the theotokos click here for icons of angels

click here for icons of angels click here for icons of saints

click here for icons of saints