I was watching a video made at Dumbarton Oaks with Robin Cormack when I came to this segment. I had to back up and repeat it six or seven times to make sure he said what thought he did. Thankfully there is a transcript on the DOAKS website so I could copy and paste this. I had never heard this story about what happened to the Beautiful Doors of Hagia Sophia:

RC: Subsequent to that work, in either the next year or the year after, having established a relationship with the director, we went out and we put scaffolding up in front of the Deësis mosaic, and we did about seven days on the Deësis mosaic, which we weren’t quite comfortable about results – we thought we dated it – we weren’t quite comfortable and so we kind of always published that in dribs and drabs. We’ve never done a full publication of our reasons for that. And we also – I have to say I can’t remember when this happened, but I spent a month with Ernest in St. Sophia when the bronze doors of the vestibule were brought back. And maybe you know what year that was but I can’t remember what year that was, but I do remember the quite extraordinary circumstance that the bronze doors had been taken down, left out in the atrium, the front of St. Sophia, had been robbed by thieves – enough of the bronze had been stolen that to – this has never really been confessed, but there were then conservationists from Rome - Madame Borrelli - did a remake of the lost bits of the bronze doors. And then – and I think they may even have been taken to Italy, but I don’t know how that was done. Then, the doors had to be put back. And Ernest and I were there, because nobody knew how to get the doors back. They’d been taken off so many years before, even the floor had been filled in and there were no workers. And it seems, judging from the photographs here in the Archive, that the only workers we could find were an aged Armenian team, and they may have been the ones that took it down – took the doors down. And it was quite extraordinary having six aged Armenian laborers putting up these massively heavy doors. And we had to dig out a hole to put the base in. We had to put them up. And we worked at night, because we tried working during the daytime but there was no – people had to come through those doors. And Ernest used to get extremely angry, because instead of going into St. Sophia they would stop and watch us digging up a hole. And I remember Ernest saying, “You’ve come to see the greatest monument that man has ever put up and all you’re doing is watching us digging a hole. Go away.” So we worked at night, which – maybe sometimes slept – Ernest had a stove and two camp beds up in one of the rooms of the gallery of St. Sophia and I feel very fortunate to have been at night in St. Sophia, because it takes people a long time to appreciate the size and scale of St. Sophia, but you sure appreciate much quicker if you’re there in the dark. So I did work with Ernest on the Deësis and on putting up those doors and obviously he was regarded by St. Sophia as an American worker from Dumbarton Oaks, but a person in his own right, as well. He played the ambiguity of his position to allow us to work there.

RR: Because when you worked with this door project, it was a secret project, right?

RC: Yes.

RR: And it was financed by –?

RC: It was financed by FIAT. For St. Sophia, though, obviously the monograms and so on are published in Dumbarton Oaks papers, so not only did I do the work in the dark, I can see my memories of it are rather obscure as well.

RR: Why was it a secret project?

RC: Because it was being covered up, that there had been damage done to the doors. And I don’t know why they were ever taken off. I think the whole episode is obscure to me.

I must say I was terribly shocked by this because I had never heard this story before so I stated to do some research on the bronze doors of Hagia Sophia. I am going to include something I found about the doors and what happened to them in an Article I found "The Emperor Teophilos (829-842). Between Classicism and Exoticism" by Siliva Pedone:

This is a real Classic “relic”, today mounted in the doorway giving access to the so-called southern vestibule, in which the famous lunette mosaic with the emperors Constantine and Justinian was found and through which you can enter the narthex and the very heart of the building. An important passage point for the visitors of the monument that however makes almost “transparent” the door itself.

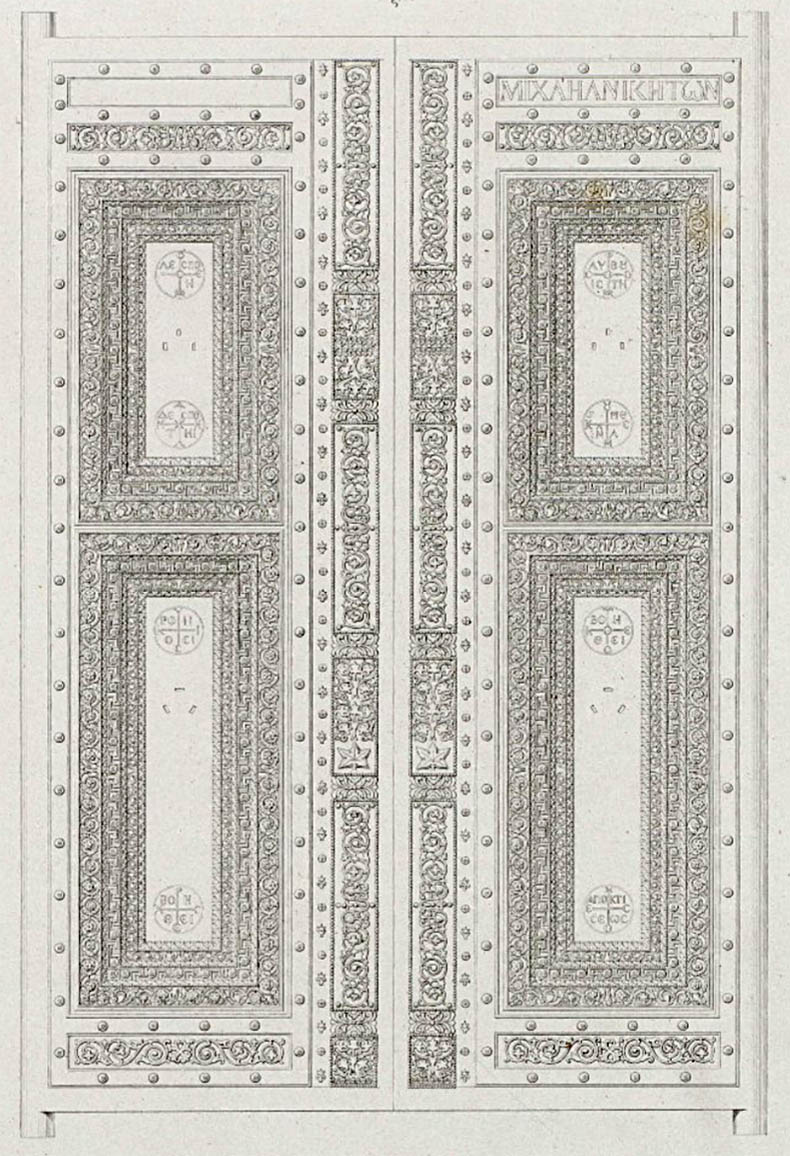

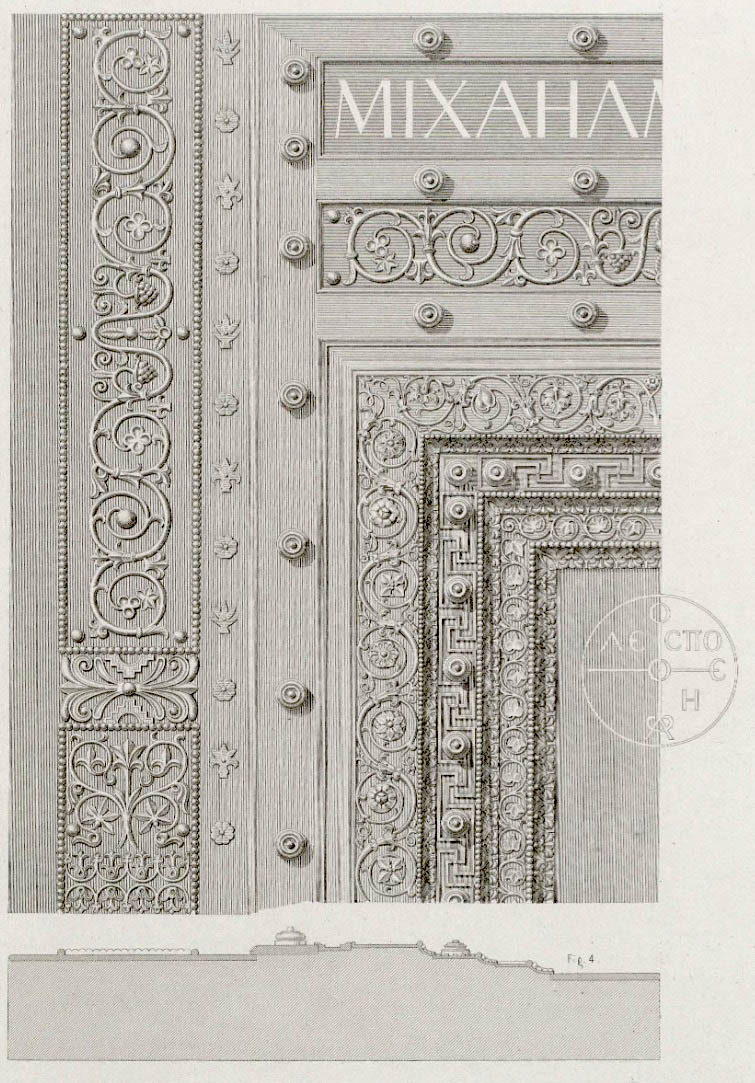

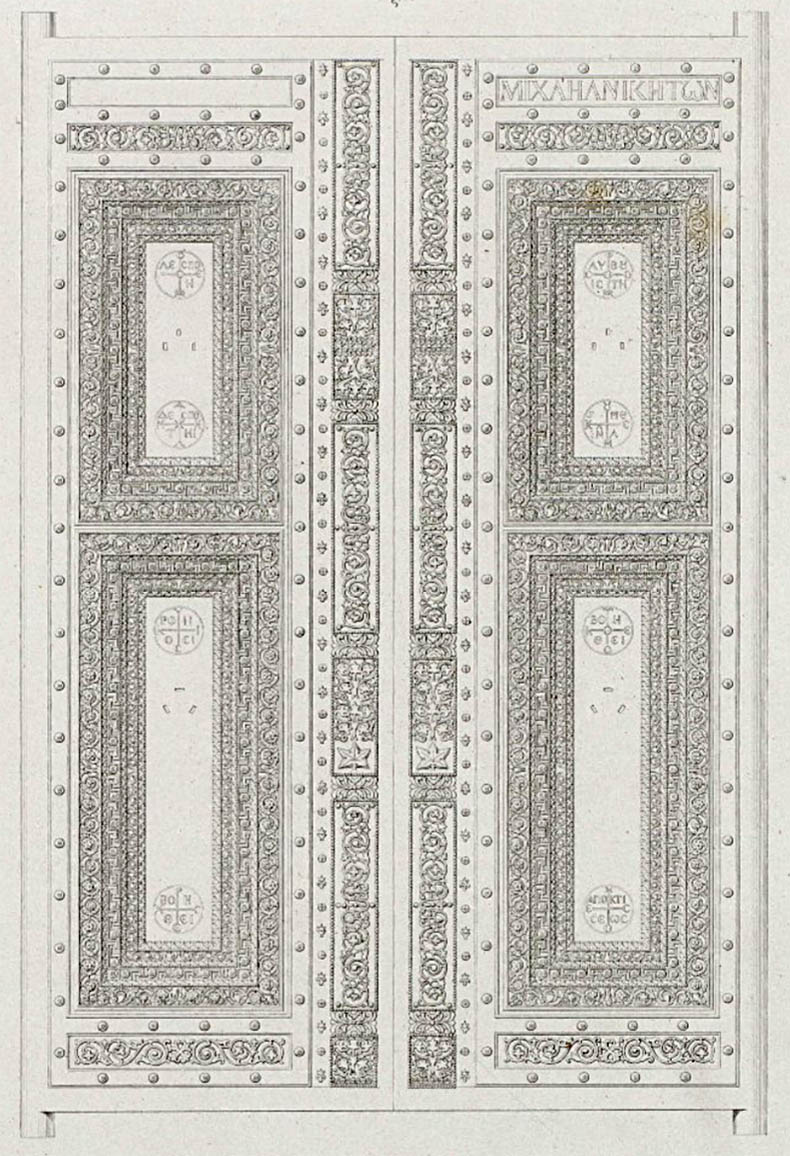

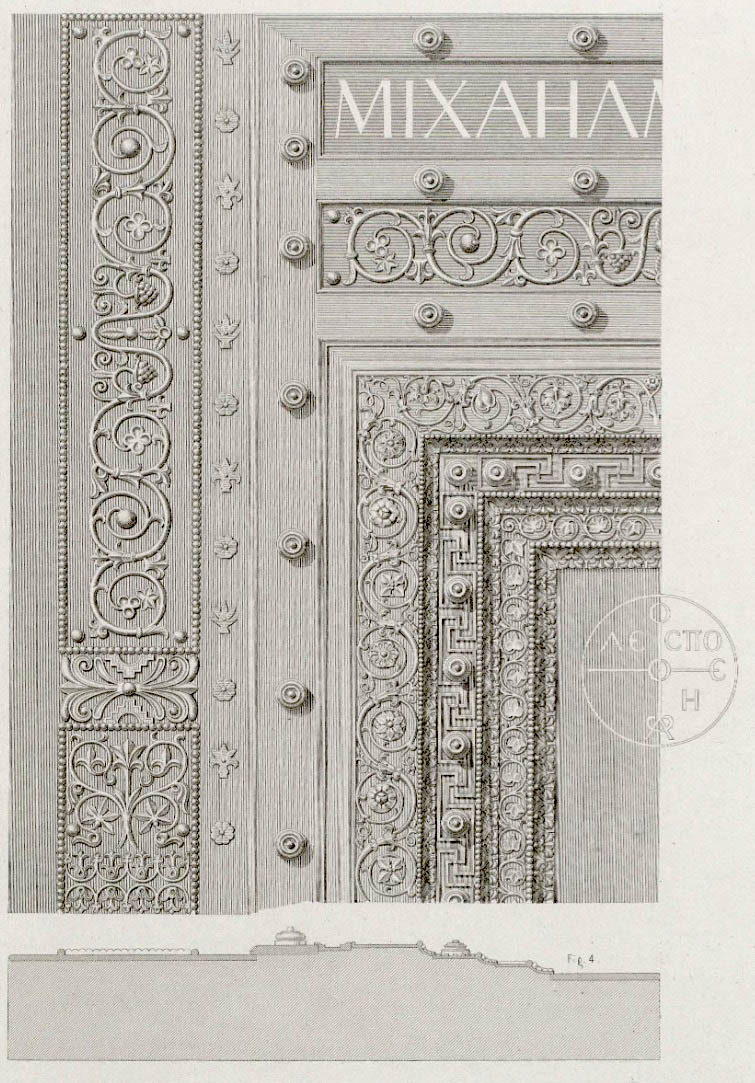

Unlike the other bronze doors still in situ, stylistically homogeneous and dating back to the Justinianic phase of the construction, our door is, on the contrary, an unicum, as a re-used Classic work, a Greek or Roman great double door of unknown provenance. The original structure was enlarged in height and width with the purpose of re-contextualizing and re-semantizing it in a different space, as a symbolic access to the starting point of the imperial liturgies. e door is documented only in late sources, and in particular it is mentioned several times in the Book of Ceremonies. Its modern location was recorded by sketches and drawings of travellers during the 19th century — as that by Charles Texier (1830s) or the engraving published in the volume devoted to the antiquities of Constantinople by Salzenberg (1854) — but also through many photographs of the end of the century .

Unfortunately, there is some uncertainty about the original position of the door and about the date of its positioning into the Hagia Sophia, also considering the lack of information about the date of construction of the vestibule and the disposition of the door, which was probably reworked several times, with the resulting raising of the original level, which occurred one more time on the occasion of the restoration carried out by Gaspare and Giuseppe Fossati by the half of the 19th century. At that time the open valves of the door were still partly recessed into the floor, so that it was impossible to move the leaves, and also the sketches we have just seen depicted only the visible portion.

Only in 1963 the researchers of “Istituto Centrale per il Restauro” of Rome (the national institute for the restoration of artworks) brought to light the lower part of the door (about 50 cm high), creating a kind of niche (or a trench) in the floor which makes it visible, established the original height of the door and discovered the early doorstep. The pieces were in a poor condition, because of the weakening of the wood structure, the detachment of the bronze foils and the loss of some applied decorative elements. The restoration works, on both structure and decoration, were carried out in two steps. In 1963 the door leafs were unhinged, consolidated and cleaned; in a second stage, ten years later, the lost parts were restored and the door settled again upon its hinges. But, in the meantime the inscription with the name of Michael (the son of Theophilos) and the broad plate with rinceaux (applied in the 9th century on the upper part of the right leaf) were stolen.

If you compare the drawings made by Salzenberg below with the pictures of the current state of the doors you can see the Michael inscription at the top is missing and large parts of the ornament have been picked off - as Robin explained. This is a very sad story, none of this needed to happen and the doors were damaged beyond repair. I wonder if bad things are still happening to them, millions of people walk by them every year and they are wide open to touch and grab. It looks to me like more bits are missing. What do you think?

Bob Atchison

Ivory of John the Baptist and Saints

Ivory of John the Baptist and Saints

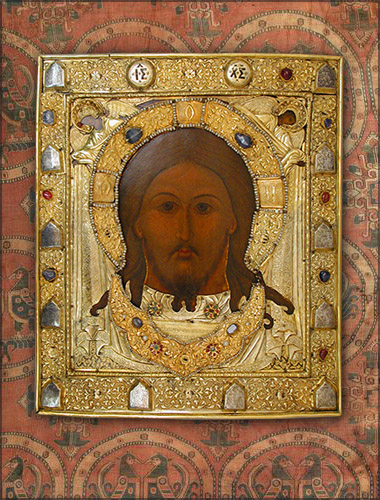

click here for icons of christ

click here for icons of christ click here for icons of the theotokos

click here for icons of the theotokos click here for icons of angels

click here for icons of angels click here for icons of saints

click here for icons of saints