![]()

![]()

Passion Relics and the Pharos Church in Constantinople

If you would like to learn more about the Maphorion of the Virgin Mary and the Holy Shroud in Blachernae visit this page

The Church of the Virgin of the Pharos - Theotokos tou Pharou - was located behind the Palace of the Boukoleon. It was one of the great landmarks of the city that sailors and travelers saw as their ships rounded the corner of the sea walls enroute to the harbor of the Golden Horn. There would have been great banners and flags flying from standards on the Imperial quay where you would land if you were visiting the emperor at Bukoleon or on your way to visit the Church of the Pharos. The whole area was protected by the English members of the Varangian Guard who wore thick silk uniforms woven with eagles covered by golden scaled armor, their heads crowned with gilded peaked helmets and their arms carrying great axes. You would have also seen court officials who wore big hats and luxurious silk robes. Many of them were clean-shaven because a large number of the emperor's attendants were eunuchs who were selected for their beauty and soft child-like voices. The quay and facade of the palace were decorated with sculptures of beasts and lions and a long loggia of marble columns. Through a great arch a long and magnificent marble staircase awaited for the ascent to the terrace where the church stood. There were so many beautiful buildings all around that it would have felt like being in a fairy-tale kingdom.

The Church of the Pharos has been described as the church-reliquary of Byzantium - its Sainte-Chapelle. It was like a giant, life-sized Faberge egg filled with treasures. But we can only imagine what it looked like because it vanished without a trace long ago. Some fragments of its decoration have been discovered - a few stray marble panels of angels and saints inlaid with semi-precious stone and glass mosaic. It stood on a high platform close to the Pharos - the lighthouse - of the Great Sacred Palace. The name Pharos is derived from the great lighthouse of Alexandria - in ancient Rome and Byzantium all lighthouses were called pharos. It was located southeast of the throne room of the palace - the Chrysotriklinos - or Golden Chamber. Nearby the church were the private Imperial apartments and a bath. Many of the top shrines in Constantinople had nearby baths, some with holy wells, so the worshiper could clean up and change dress before entering the sanctuary.

In Byzantium Imperial court ceremonial had religious overtones. The old Roman ways of the Caesars had been merged with Christian festivals and liturgies. The emperor was considered a sacred figure, not divine but somehow closer to God than the average man. The daily court rituals followed the hours of church services. Throughout the day, from the emperor's rising until bed there were prayers and short services that required a nearby chapel. Even during the night the ruler awoke for private devotions in a close-by chapel. The Pharos Church was positions just outside the Imperial bedroom which communicated with it by a private passage and door. It was kept continuously in operation 24 hours a day awaiting the visits of the emperor and his wife. The church was always lit by candles and oil lamps, the air was scented by incense. Not only was the chapel the heart of religious life in the inner sanctum of the palace, the narthex of the church connected directly with the Imperial treasury.

Naturally very few people were allowed to visit the Pharos church. The special ceremonies associated with the relics in the church were attended by members of the family and a few close friends. However, the relics the church contained were the number one objective and destination of every pilgrim who entered the city. The Passion relics were annually transferred from the chapel to Hagia Sophia at Easter, but during the rest of the year you could visit the church and venerate them with special permission from the emperor. Pilgrims came from all over the world at Easter to see the Passion relics in Hagia Sophia when 100,00 or more streamed past them in a single day.

On the right is a gilt-silver reliquary box from the the Church of the Pharos that enclosed a piece of the tomb of Christ. It dates from the 12th century and was taken to France after 1204 in the sale of the relics to the French king.

On the right is a gilt-silver reliquary box from the the Church of the Pharos that enclosed a piece of the tomb of Christ. It dates from the 12th century and was taken to France after 1204 in the sale of the relics to the French king.

It was considered a tremendous honor when Manuel I Comnenus personally conducted King Louis VII of France and his wife Eleanor of Aquitaine on a tour of the church where they were allowed to hold the relics in their cases. A few days later Manuel conducted his brother-in-law, the German Emperor Conrad, on another visit to the chapel. The tours were attended by members of their entourages, everyone wanted to be invited on the tour. Venerating the relics would have been the high point of their visit. They were all in Constantinople on the way to the Holy Land during the second crusade and would have experienced the overwhelming emotion of encountering Christ first-hand through His relics. There was nowhere in the West that had personal relics like this. The experience would have been heightened by the breath-taking beauty of the church and the chanting of the famous eunuch singers of the Imperial choir who sang for the Emperor in the palace and were loaned to Hagia Sophia on occasion. The singers combined chanting with graceful movements of the head and arms, which the crusaders found strange and especially enchanting. The clergy who served the Imperial family were also brought in for these royal visits. Manuel may have spoken to his visitors in French. His wife, the German Princess Bertha, would have also accompanied them.

The visits would have been followed by a meal, either breakfast or lunch. For generations, the emperor frequently hosted banquets at the church.

There was a special ceremony held annually in the narthex of the Pharos church where the emperor presented two apples and a stick of cinnamon to members of the court. The Byzantines believed that giant "cinnamon birds" collected the cinnamon sticks from an unknown land where the cinnamon trees grew and used them to construct their nests. Cinnamon as a spice and aromatic was much appreciated by the Byzantines.

The Byzantine princess, Anna Comnena, describes the bedroom and the chapel which was connected to it by a door, which she knew well:

"This imperial bedroom, where the Emperors then slept, was situated on the left side of the chapel in the palace dedicated to the Mother of God; most people said it was dedicated to the great martyr Demetrius. To the right was an atrium paved with marble. And the door leading to this from the chapel was always open to all. They intended, therefore, to enter the chapel by this door, to force open the doors which shut off the Emperor's bedroom and thus to enter and dispatch him by the sword".

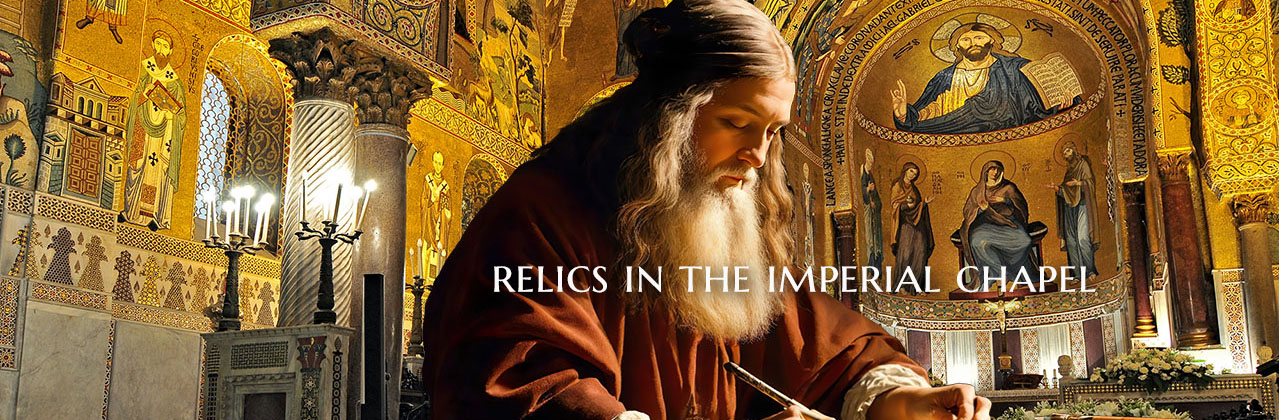

There were around 30 churches and chapels in the territory of the great Sacred Palace. They ranged from big and impressive to small and intimate. The Pharos church was considered small in comparison to nearby churches like the Nea. To understand its size we should look to the Capella Palatina in Norman Sicily which directly copied the Church of the Pharos in size and in the beauty of its decoration. It is believed the original Church of the Pharos was built by the iconoclastic Emperor Constantine V - called Kopronymos (poop head) - and it served as his personal Imperial chapel. After the restoration of icons the church was renovated or even rebuilt by Emperor Michael III who reigned from 842-867. Michael had the sarcophagus of Constantine V removed from the mausoleum of Justinian near the church of the Holy Apostles, and cut it apart to make chancel panels for the church. The church was a four-columned cross-in-square with three apses. The dome was small. It had a narthex and an atrium. The re-dedication took place in 864 and the patriarch Photius delivered a homily to celebrate the occasion in which describes the church. From this document we can obtain many details about it. Photius writes:

"But when with difficulty one has torn oneself away from there and looked into the church itself, with what joy and trepidation and astonishment is one filled! It is as if one had entered heaven itself with no one barring the way from any side, and was illuminated by the beauty in all forms shining all around like so many stars, so is one utterly amazed. Thenceforth it seems that everything is in ecstatic motion, and the church itself is circling round. For the spectator, through his whirling about in all directions and being constantly astir, which he is forced to experience by the variegated spectacle on all sides, imagines that his personal impression is transferred to the object"

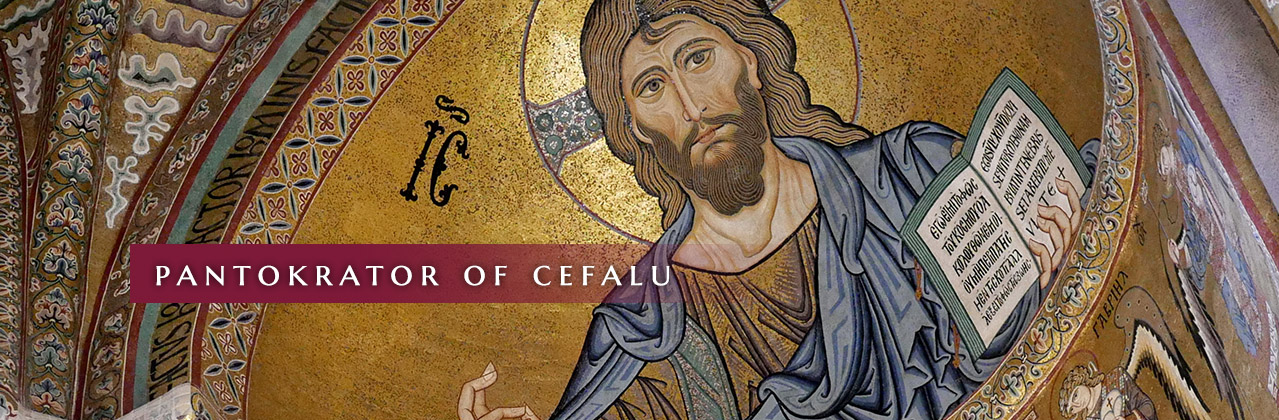

Photius also tells us that the church was entirely faced in white marble. The interior architecture had many arches and vaults and the walls were covered in rare polychrome jasper and marble revetment of many colors - laid in patterns to show off the grain and patterns in it. The floor was set with an opus sectile floor inlaid with beasts, sea creatures and mythological figures. The four columns had silver capitals with gold bands at their base. There was a mosaic of Christ Pantokrator in the dome with angels below. In the apse what the Theotokos extending her hands in prayer and blessing. The walls were covered with saints, some of whom held scrolls with inscriptions. This all sounds very much like the Palatine Chapel in Norman Sicily, which performed a similar function and had the same richness in it's decoration. Some of supposed that at least the chapel's mosaics were done during the Comnenian dynasty, which would be at the exact time a the Palatine Chapel. Perhaps the same artists worked in both places. Since the Pharos chapel has vanished we will never know for sure.

The crusader Robert of Clari - who saw the chapel described it:

"More–over, there were full thirty chapels there, both large and small; and there was one of these which was called the Holy Chapel, that was so rich and so noble that it contained neither hinge nor socket, nor any other appurtenance such as is wont to be wrought of iron, that was not all of silver; nor was there a pillar there that was not of jasper or porphyry or such like rich and precious stone. And the pavement of the chapel was of white marble, so smooth and so clear that it seemed that it was of crystal. And this chapel was so rich that one could not describe to you the great beauty and the great magnificence thereof. Within this chapel were found many precious relics; for therein were found two pieces of the True Cross, as thick as a man’s leg and a fathom in length. And there was found the lance wherewith Our Lord had His side pierced, and the two nails that were driven through the midst of His hands and through the midst of His feet. And there was also found, in a crystal phial, a great part of His blood. And there was found the tunic that he wore, which was stripped from Him when He had been led to the Mount of Calvary. And there, too, was found the blessed crown wherewith He was crowned, which was wrought of sea rushes, sharp as dagger blades. There also was found the raiment of Our Lady, and the head of my Lord Saint John Baptist, and so many other precious relics that I could never describe them to you or tell you the truth concerning them."

The Byzantine scholar and historian Nicholas Mesarites describes it as well:

"...magnificent church, expensive silver, costly pearls, priceless emerald, precious red gems and abundant gold. The katapetasma of the church is all silver and the columns supporting it are silver and gold plated, luminous, sparkling. From the tetragon the katapetasma like a geometric pyramid recedes to a sharp point. Life-giving true crosses are covered with gold from one edge to the other. The precious stones are fastened to them in abundance, fixed, planted in are the pearls rounded off in perfect shapes. The doves hover over the holy table, they are not silver or gold plated, but entirely, and their backs too, shine with yellow gold. The wings are adorned with emeralds, illuminated by the pearls pierced through, the feathers are loose: as if they were hovering in the air and have just stopped for a rest. Their beaks hold young branches, not those with olives but with pearls and the branches are cross shaped..."

Mesarites is especially interested in the connection of the relics in the church to the events of Christ's life and passion in the Holy Land and the Imperial status of the chapel. He notes that the church was so beautiful that it had special glass mirrors in adjustable wooden frames to reflect more light into the church. This also indicates how small it must have been and full of precious things. These reflective mirrors could have been used to cast light on the relics that were displayed here.

During iconoclasm the emperors preserved and honored the relics of Christ's Passion and the Maphorion of the Virgin. The relics were not images, nor were they parts of the bodies of saints, so they were in a unique category. The TrueCross The iconoclast Emperor Theophlius had the maphorion and reliquaries of the True Cross carried in processions in Constantinople. He especially favored the shrine of the Virgin of Blachernae where the maphorion was housed and visited it on many occasions. He refurbished a nearby palace so his daughters could easily visit the church.

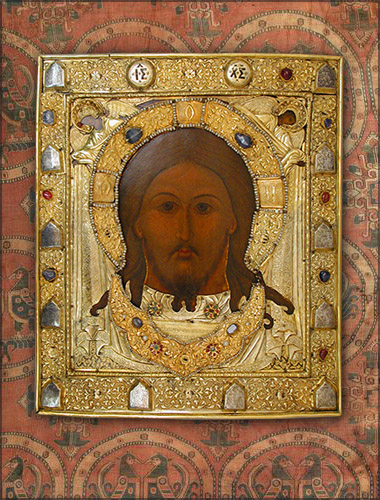

There were two GREAT churches for the relics of the Passion in Constantinople. One was the enormous Hagia Sophia and the other was the Pharos church. Pilgrims were sure to visit them both when they visited the city. In the Pharos church were to be found the Mandylion and the Karamion. The Mandylion was the famous image of Christ that was said to have been imprinted on cloth and sent to King Agbar of Edessa and a gift in place of His coming to Edessa as invited by the King to heal him. In the 10th century there were two copies of it in Edessa, along with the original. When it was decided by the Abraham, the bishop of Samasota to send the Mandylion to Constantinople he insisted that all three copies be obtained as a group as shipped together. The people of Edessa rioted to prevent the loss of their most precious relic, but Abraham managed to make it to the banks of the Euphrates, where the bishop's boat miraculously crossed the river at breakneck speed with the use of oars or sails. It stayed for a short time in Edessa where it performed miracles before heading for Constantinople by land.

Thus the Mandylion came to Constantinople during the reign of the Emperor Romanos I Lekapenos, arriving on August 15th in 944. It spent it first night in Constantinople at the Church of the Blachernae, the next day it was taken by the co-emperors in procession around the sea and land walls of the city, then through the Golden Gate to Hagia Sophia. Miracles followed the Mandylion as it processed through the city, including a paralytic who was cured by the mere sight of it, despite the fact that the image was very faded, smudged and hard to make out. There were four co-emperors at the time - Romanos I, his two sons and Constantine Porphyrogennetus. Constantine was able to see the image very clearly, but to his two "wicked" co-emperors, the Lecapeni brothers (notorious drunkards), the image was blurred. Indeed, the Mandylion, was a disappointment to see, unless you had faith. The Icelandic Viking pilgrim and traveler, Abbot Nicholas Bergsson of Thingeyrar, who visited Constantinople around 1150, and reported on the relics in the Pharos Church, wasn't sure what the Mandylion was. After its stay in Hagia Sophia the Mandylion was displayed in the Great Palace where it was placed on the Imperial throne; and then finally placed in the Pharos church along with the letter written by Christ that accompanied it when He sent His image to King Agbar.

The Keramion, the miraculous imprint of Christ's face in the Mandylion on a tile, arrived at the Pharos Church in 968, twenty years later, brought there by Nikephoros II Phocas. The Mandylion and the Keramion were suspended from the vaults of the church and were covered with veils. They were hung facing one another with a lamp hung between them. This lamp was though to be miraculous with the light never dying out, being continuously filled with oil by the mysterious power of God.

A few years later, in 975, John I Tzimiskes added the sandals of Christ to the collection.

Robert of Clari describes how the Mandylion and the Keramion were displayed in the Church of the Pharos:

"Now there were yet other holy relics in this chapel, of which we had forgotten to tell you. For there were two rich vessels of gold which hung in the midst of the chapel by two great chains of silver, and in the one of these vessels was a tile, and in the other a towel. And we will tell you whence these relics had come.

There lived of yore, in Constantinople, a certain holy man. And it chanced that this holy man was mending with tiles the roof of a widow woman’s house, for the love of God. And as he was mending it, lo, Our Lord appeared to him and spoke to him; and the good man had a towel girt about him. “Give thither,” said Our Lord, “that towel.”

And the good man yielded it to Him. And Our Lord wrapped His own face therein, so that the likeness thereof was imprinted upon the towel; then gave He it back to him. And He told him that he should carry it away, and lay it on sick folk, and that whosoever had faith therein, he would be cleansed of his sickness. And the good man took it and carried it away. But before he carried it away, when God had given his towel back to him, the good man took it and hid it under a tile until the evening. In the evening, when he went thence, he took the towel; but as he lifted up the tile, he saw the likeness imprinted upon the tile also, even as upon the towel. And he carried away both the tile and the towel, and thereafter were many sick folk healed by them. And these relics hung in the midst of the chapel, even as I have told you.

Now there was also in this chapel another holy relic, for there was to be seen therein a likeness of Saint Demetrius, which was painted upon a board. This likeness gave forth so much oil that it was not possible to remove all the oil that flowed ever downward from this picture.

And there were some twenty of these chapels, and there were some two hundred chambers, or three hundred, which all adjoined one to another, and they were all wrought in mosaic of gold. And this palace was so rich and so magnificent that one could not describe or relate to you the magnificence and richness thereof."

The Mandylion arrived in the city to wild and enthusiastic demonstrations of the people and the nobles. Many other relics were here particularly centered on the Passion: the Crown of Thorns, the Holy Nail, Christ's clothes, purple mantle and reed cane, and even a piece from his tombstone.

The relics in the chapel were frequently moved to other churches and called upon to save the city in times of great trouble, like famines and droughts. They were carried in great processions to Hagia Sophia, the Blachernae and other parts of the Great Palace, and they could be taken out to participate in special liturgical processions, spectacular events that pleased - and entertained - the population of Constantinople. Once a year, in August, the True Cross was brought out and processed through the city. The relics would be placed in chests of gold and silver-gilt with enamels, jewels and pearls and carried by members of the Imperial family on foot. These processions were important events on the civic and religious calendar when citizens would dress up in various costumes and factional colors, displaying carpets and tapestries from balconies. The streets were strewn with rosemary, camomile and grape leaves which released their scent was the procession trod upon them.

The Byzantine scholar, Thomas Thomov, has recently discovered a 14 line inscription in old Russian carved into a column in the North Gallery of Hagia Sophia which reads:

“So I, Fyodor venerated the Holy Passion relics.

So I, John venerated the Holy Passion relics.

So I, Kosmas was the third one; I venerated the Holy Passion relics,

I was the third one.

So I, ..."

He dates the inscription to the 15th century and believes it to have been inscribed by a Russian pilgrim who was a not a member of the clergy because he did not say "I, Kosmas, servant of Christ". It was carefully carved during Holy Week when the Passion relics were displayed in Hagia Sophia to huge crowds. The Russians, like Kosmas, usually came to Hagia Sophia in groups. The column Thomas Thomov found it on appears to have been a favorite for pilgrims to leave messages on, it is in the far eastern bay, close to the altar.

Early on there were relics to be seen in the church. In 675, before Iconoclasm, the Gallic bishop Arculf, in the earliest Western account of Hagia Sophia, reported he saw the True Cross on display in the north aisle, where it was kept in a reliquary. It was brought out in its wooden box during Passion Week for veneration. The box was kept on a special table which he describes as an altar, and he says the True Cross was assembled from three pieces of wood. A separate day for veneration was assigned for men on Good Friday, a second day for women, and a third day for the clergy. He says that the chest, when opened to show the cross, put off a beautiful sweet smell.

There was a gilt silver reliquary containing fragments of the Passion relics that was displayed in a large standing crucifix near the entrance to the Chapel of the Holy Well in the far eastern corner of the nave of Hagia Sophia, near to the Imperial dressing room. This seems to have been a stand-in for the Passon relics themselves which were on display once a year in Hagia Sophia. It was probably something like the Limburg Staurotheke which will be mentioned later on. Everyone who passed by it would venerate it. It seems to have disappeared in 1204.

On at least one occasion there was an attempt to steal a relic. During the reign of Alexis I Comnenus, Gregory, son of Theodore Gabras, one of his military dukes and a Georgian aristocrat, was being held as a hostage in the palace. Alexis had decided to marry Maria, one of his daughters, to him as a bargaining chip with the man's father, who was Duke of Trabzon. Theodore had recently re-conquered Trabzon from the Turks and - in the hopes of securing the region - had been assigned to him as a new dukedom by Alexis. The son, Gregory, was sent to the Pharos church to remove and then swear on the relic of the Holy Nail that he would marry the sister and take an oath to Alexis. Somehow he concealed the Holy Nail in his clothes and was about to leave the city for his father's lands when one of his co-conspirators spilled the beans. He was caught and searched; the Holy Nail fell from his clothing, the precious relic clanking as it hit the floor -and was returned to the Pharos. Gregory did marry Maria but the marriage was later annulled. This story shows us that the chapel was not closely guarded and that you could easily get your hands on things. The church was within a special walled enclosure that included the Boukoleon. Even though the chapel was open it was not thought necessary to place guards inside.

We don't have a precise date for when the Crown of Thorns came to Constantinople. One French account says it arrived in Constantinople in 1063, but no Byzantine records to support this. It seems to have been in Jerusalem at least as early as the late fifth century. In the 500's it hung on a wall of the great Zion church that Justinian I built there. The relic was not safe in Jerusalem, in 614 the Persians sacked and looted Jerusalem, taking many of the valuable relics - like the true cross - back to Persia. The True Cross was recovered by Heraclius and returned to Jerusalem, perhaps the Crown of Thorns followed the same path. Justinian's huge 80-column church of Zion was heavily damaged in the Persian sack and was finally demolished by the mad Caliph al-Hakim 1009, so the Crown of Thorns must have left Jerusalem before that. In 798 the Byzantine Empress Irene made gift of thorns taken from it to Charlemagne. We know the Crown of Thorns was in Constantinople by around 950, because there is golden chamber for a piece of it in the great Limburg Staurotheke commissioned by Basil the Proedros which is firmly dated no later than 985. The inscription identifying it reads "The Thorny Crown of the philanthropic Christ and our God."

In 1201 Mesarites described the Crown of Thorns. Mesarites was in charge of all of the relics at the Pharos Church and knew it from personal observation:

Hear from my lips the divine account, and learn how these ten treasures are called. [...] First, there is the Crown of Thorns displayed for veneration, still fresh and green and unwithered, since it had a share in immortality through its contact with the head of Christ the Lord, refuting the still-unbelieving Jews, who do not bow down to worship the cross of Christ. In appearance, it is neither rough nor stingy or harmful in any way, but instead looks like it was made from beautiful flowers. If one were allowed to touch it, it would feel smooth and lovely. The branches from which it was wrought are unlike those that grow in the hedges of the vineyards, which catch the dips and hems of garments like street robbers catch their pray, or which sometimes scratch a foot with their thorny tips and draw blood when one passes by, no, nothing like this at all. Rather, they resemble the blossoms of the Frankincense tree, which grow as tiny shoots on the knots of their branches much like small leaves.

Over the years 75 thorns were detached and sent to various rulers, bishops and religious institutions. There are no thorns remaining on the Crown of Thorns.

In 1204 the Fourth Crusade brought the collection of relics to an end. For weeks before the city walls were scaled by the crusaders huge parts of the city had been burnt in gigantic fires that snaked through the city - devouring everything in their path. Hagia Sophia was spared - barely - the atrium of the great church was partly destroyed. When the city fell it was sacked completely. The Church of the Theotokos in Blachernae, where the Maphorion of the Virgin and the Holy Shroud were displayed, was looted and the Holy Shroud vanished along with the famous miraculous icon of the Theotokos called the "Great Panagia". Amazingly the church of the Pharos was spared. Looking for members of the Imperial family - especially the women - Boniface of Montferrat moved swiftly to occupy the area of the Boukoleon Palace and seized the Pharos church at the same time. Geoffrey of Villehardouin, Marshal of Champagne and of Romania, participated in the Fourth Crusade and wrote an account of it called "On the Conquest of Constantinople". About Boniface of Montferrat and the Boukoleon he wrote:

"...rode all along the shore to the palace of Bucoleon, and when he arrived there it surrendered, on condition that the lives of all therein should be spared. At Bucoleon were found the larger number of the great ladies who had fled to the castle, for there were found the sister of the King of France, who had been empress, and the sister of the King of Hungary, who had also been empress, and other ladies very many. Of the treasure that was found in that palace I cannot well speak, for there was so much that it was beyond end or counting."

All the relics were preserved, untouched in their jeweled cases. They became the property of the first Latin Emperor, Baldwin I. Both the Pharos and Blachernae churches, which were attached to palaces, were given to the French as the personal property of the new Latin Emperor. The Venetians took over the Patriarchal Palace and Hagia Sophia, where they ejected the Greeks and installed Venetian clergy and Canons. In 1205 the Crown of Thorns was used to secure a large loan by the Barons of the Latin Empire from a Venetian living in Constantinople, Nicolo Querini. It was then transferred to the treasury of the Pantokrator Church, which was occupied and used as the headquarters of Venice in the city after the conquest. The Crown of Thorns was held there by the Camerarius of the Venetian Commune in Constantinople. This loan appears to have been repaid because in 1235 the Latin Emperor John of Brienne was granted a new loan by the Venetians using the Crown of Thorns and other passion relics as security for it. The Barons were unable to repay this loan which was due in 1238 and the relics remained in the hands of the Venetians at the Pantokrator until they sold them to the French.

Ten years later, in 1248, King Louis IX of France secured the Crown of Thorns and other relics of the passion for his own Pharos church - the famous Sainte-Chapelle. The king paid 155,000 livres for them, which was half of the annual income of the kingdom. It's possible that they were still in their original silver-gilt and jeweled cases, since there are drawings of them from Sainte-Chapelle before the French Revolution, when they were lost. When the relics arrived in France they still had the scent of balsam attached to them. Aleksei Lidov, the famous Russian Byzantine scholar, has called Sainte-Chapelle a "Gothic replica of the Theotokos of the Pharos". A part of the True Cross, the Crown of Thrones and one Holy Nail survived the Revolution and can be venerated in France today. Here's a picture of the Crown of Thorns below, all of the thorns have been detached over the years..

The Crown of Thorns that Louis received was made of a wreath of Juncus balticus rushes, commonly called Baltic rush. Intertwined with it were branches of Ziziphus spina-christi, known as the Christ's thorn jujube, which grows near Jerusalem. There is a 2,000 year old tree of Christ's thorn jujube growing south of the city that is said to be the very tree used in the Crown of Thorns. It is unclear how and when Baltic Rush was woven into the Crown of Thorns, Robert of Clari says the Crown was woven with sea rushes when he saw it in the early 1200's. Mesarites is the best description of it; "still fresh and green - beautiful flowers- smooth and lovely - thorny tips - blooms of the Frankincense tree". Is it possible the rushes were renewed after the crown arrived in France? That could explain the presence of Baltic rush from Northern Europe.

In 1247 the Mandylion also ended up in Sainte-Chapelle, where it was listed in many inventories as the "Holy Towel", and was thought lost in 1792 during the French Revolution, It was always hard to see, but every vestige of facial features has vanished. It seems to have been almost forgotten and nobody recognizes it as the Mandylion anymore. There was another Holy Towel in the collection of relics kept in the Pharos Church which is called "The Towel of the modeler, Christ (the son) of God" on the Limburg reliquary which contained a fragment of it. This was said to have been the towel Christ used to wash the feet of the Apostles. It was a plain towel with no image on it.

It's an interesting related story that the famous Hodegetria icon of the Theotokos (the Byzantines believed it had been painted by St. Luke) which ended up in Hagia Sophia just after the sack of city in 1204 became another scandalous tool in the hands of the Venetians. In 1206 they forcefully stole the icon from the Latin Patriarch, Tomaso Morosini, which was in Hagia Sophia, and removed it to the south church of the Pantokrator where they could control access to it in their headquarters. It is no surprise that the Venetian Quarter in Constantinople was not burned in the great fires that swept the city in 1204 which had been set by the crusaders to drive the urban population from the city in advance of their invasion.

It is possible that the Holy Face of Genoa is the Karamion. How and why it could have remained in Constantinople - and was not sold to the French - is unknown. The Holy Face was a gift from the emperor John V Palaeologus to the doge of Genoa Leonardo Montaldo in a desperate effort to gain support for his war against the Turks. It is painted on cloth that has been mounted on wood, and is set in a magnificent filigree frame, which is lined in Imperial red Byzantine silk. It is a rare example of late Byzantine silver-gilt work. John V considered the Holy Face to be the most precious of his possessions.

The idea that the Mandylion was the Sidona - the Shroud of Christ - folded up to just show the face - is without any basis in fact. Robert of Clari tells us that the Sidona was displayed at the Blachernae church it was placed on a mechanism that unrolled it to show the the body from the waist up. He saw it up close. You could plainly see the features of the body and especially the face. It is interesting the Holy Shroud of Turin was folded in just such a way. Nicholas Mesarites describes the Holy Shroud - the winding sheets:

"The burial sheets of Christ:

They are of linen, cheap and simple material, still breathing with myrrh, defying destruction, for they winding the uncircumscribed one, a naked body after the passion"

It is obvious that the appearance of altar cloths decorated with the body of Christ is directly related to the Shroud which was kept in Constantinople at least until 1204. Threads from this shroud were preserved in the Limburg reliquary. I don't know if they are still there. The inscription reads "The Shroud of the everlasting Christ and God". It would be interesting to compare these threads with the Shroud of Turin. If there was a match it would overturn the carbon dating of the Shroud and confirm that it was in Constantinople in the tenth century.

The Limburg reliquary (shown above) was portable and could be displayed on a pole. It is said the reliquary was carried by emperors on military campaigns and displayed to the troops. It would have been kept in the Imperial tent. It was probably kept in the Pharos church when it was home in Constantinople.

The Limburg reliquary (shown above) was portable and could be displayed on a pole. It is said the reliquary was carried by emperors on military campaigns and displayed to the troops. It would have been kept in the Imperial tent. It was probably kept in the Pharos church when it was home in Constantinople.

Some relics were to be found in Constantinople after the recovery of the city by Michael VII in 1271. Even these were soon in danger due to the financial peril the empire found itself into. The personal accounts of the Imperial family were especially threatened. In 1356 Empress Helena Kantakouzene , wife of John V Palaeologus and mother of Manuel II sold priceless relics in their settings. They included Drops of Christ's Blood, a piece of the Tunic of Christ, the Sponge, the Swaddling Clothes, the precious wood of the cross, a relic of John Chrysostom and a piece of the Holy Girdle of the Theotokos. For all of these she raised 100,000 hyperpyra from a Florentine merchant in Pera. The crown jewels had already been sold for 60,000 hyperpyra.

Later, in the reign of Manuel II, around 1400, the emperor was forced to sell - or offer in exchange for military aid - pieces of one of the two tunics of Christ that were in his possession. Manuel had one of them cut into small pieces.

One of the tunics was called the purple and the other was called the seamless one. Both were recorded in Constantinople before 1204 and somehow had remained in the city. The seamless robe was described as being woven in heaven and was the one the soldiers had cast lots. It had been dark red at one time, but had faded to grey - violet. It was kept in a silver box and kept with the other Passion relics, you could only see a sleeve of it in 1430. A few pieces were already missing from it, which had been stolen by pilgrims. This tunic might have survived 1453 - one was offered for sale in the west after the conquest. The other tunic was blue. Potential buyers were put off because there had been some concern that the tunic was not the genuine relic. Manuel had success in offering pieces as gifts - he received six armed galleys from the King of Spain in exchange.

One can speculate on the demise of the Church of the Pharos which occurred sometime after 1204 and before 1271. It is possible that the church was a victim in the quake of 1231 - too heavily damaged to be repaired. The remains may have been cleared away and sold as building supplies to the Venetians. The Palace of Bukoleon was chosen as the official residence of the Latin Emperors in the first years of their occupation, but they abandoned it in favor of the Blachernae palaces where they moved permanently in the last years before the recovery of the city by the Greeks. Perhaps the Bukoleon was damaged in the same earthquake. There is no mention of the Church of the Pharos after the reconquest of the city.

Bob Atchison

click here for icons of christ

click here for icons of christ click here for icons of the theotokos

click here for icons of the theotokos click here for icons of angels

click here for icons of angels click here for icons of saints

click here for icons of saints