I have created a special page on the doors of Hagia Sophia with many of the doors from the inner and outer narthexes of Hagia Sophia - click here to see pictures and learn more about them.

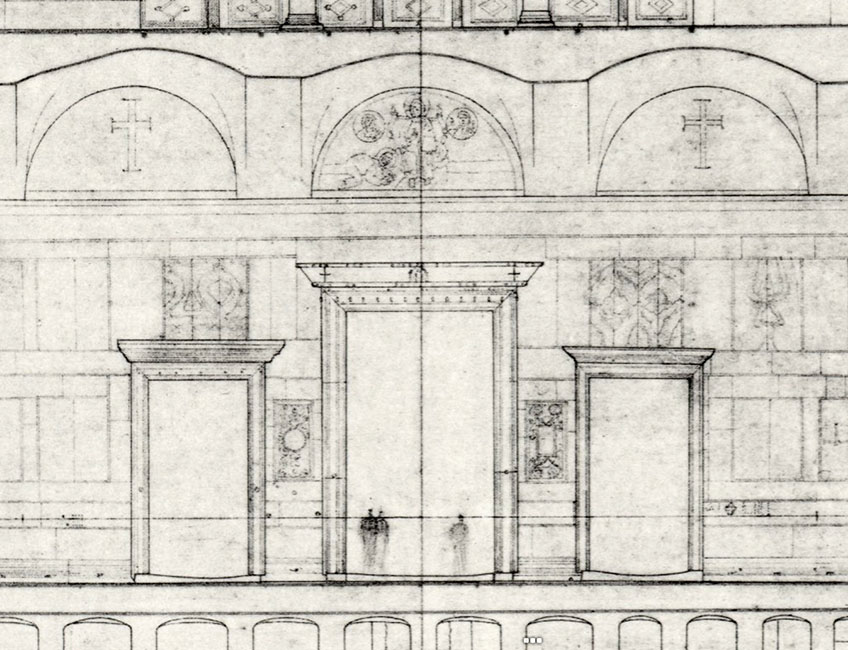

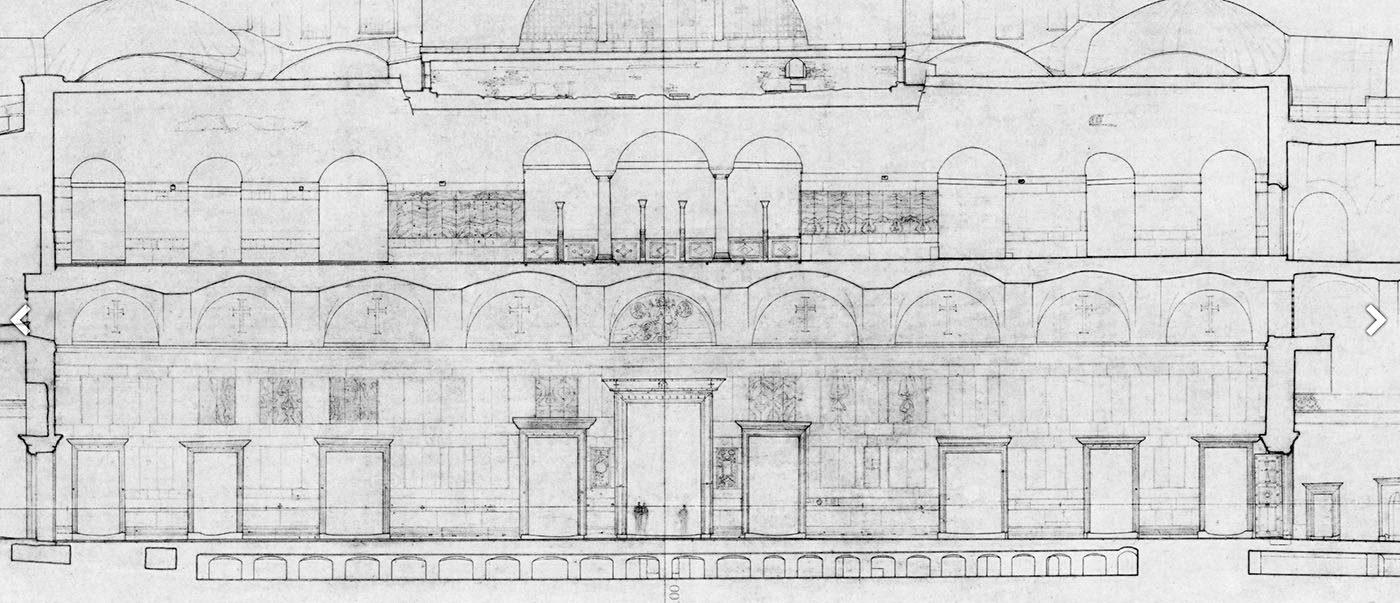

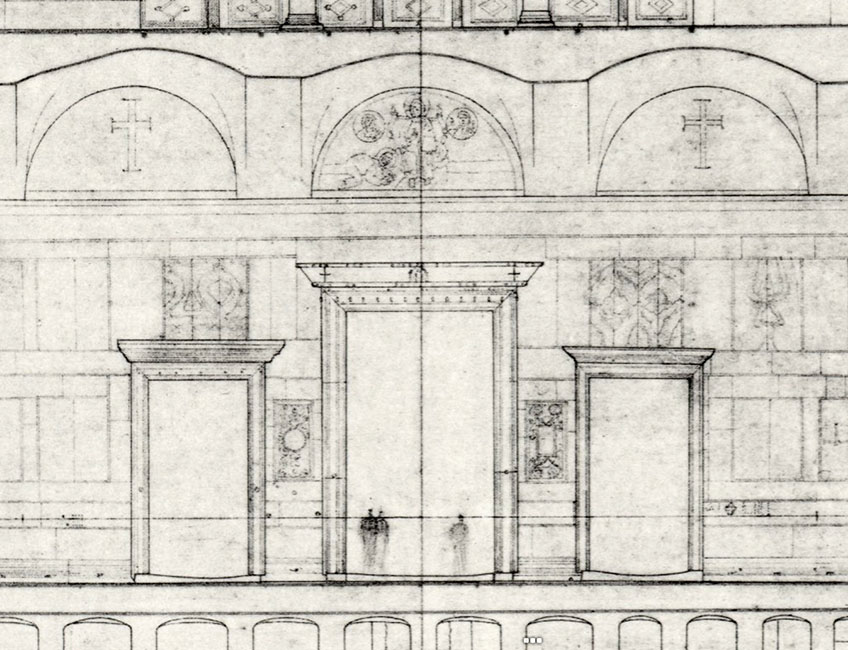

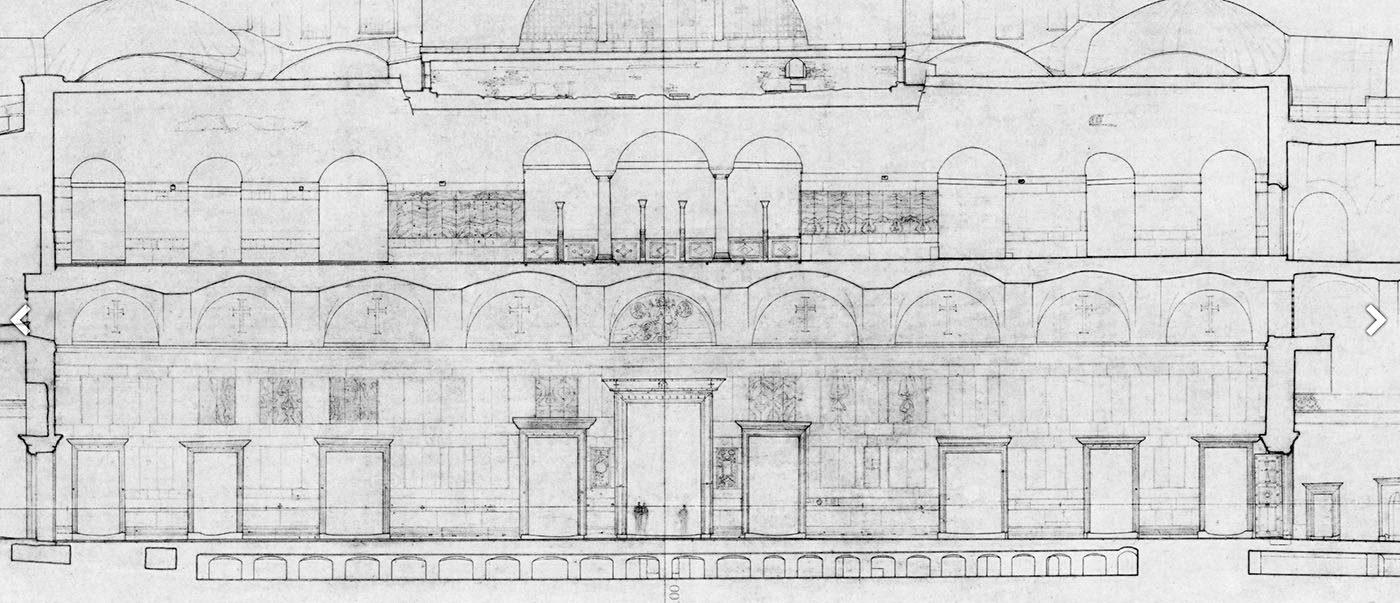

The outer narthex is extremely simple, and hardly seems part of tho original design; 5 doors lead from it to the inner narthex, which was set apart for penitents and catechumens. In contrast, the inner narthex is a splendid hall, 205 ft. in length internally, by 26 ft. wide, and two stories in height. Its walls are re vetted with variegated marbles, and its ceiling glitters with mosaics. The center door is best known for its mosaic of Leo VI, which was the first mosaic uncovered by the Byzantine Institute starting in December 1931, which was completed in September 1932. The restorers were learning on the job, so to speak, carefully exploring and implementing new techniques for cleaning and consolidating mosaics. The mosaic had been already known through Saltzenberg's reproduction of it in his famous book on Byzantine architecture. He saw it uncovered while the Fossatis were at work in the mosque. It had been covered up again on orders of the Sultan when the Fossatis finished their work.

Kemal Attaturk, the President of the Turkish Republic closely monitored the work of the Byzantine Institute in Aya Sofya and received Thomas Whittemore in Ankara on July 11, 1932 to discuss it with him and look at photographs. In their meeting Attaurk learned more about Byzantine architecture and offered the comment that Sinan and later Turkish architects had exceeded Aya Sofya in scale and beauty. It was decided and decreed that the mosque would be reopened as a museum of Byzantine art with Ottoman works in appropriate places.

Leo VI was called the Wise for his completion of the compilation of a great law code in Greek for the empire, called the Basilika. He was the second son of the previous emperor, Basil I and Eudokia Ingerina. Leo was actually the son of the precious emperor Michael the Drunkard, which is a long story best told in its own page. Basil knew Leo was not his son; Leo also knew who his real father was.. As result, Basil treated him badly; he favored his first, natural son, Constantine, over Leo. Even though Basil had Constantine and Leo crowned as co-emperors, he excluded Leo from any role in government or the military. He finally shut Leo up in captivity within the palace grounds.

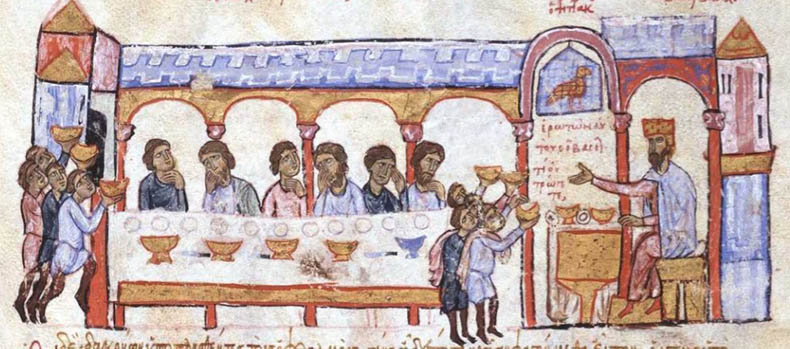

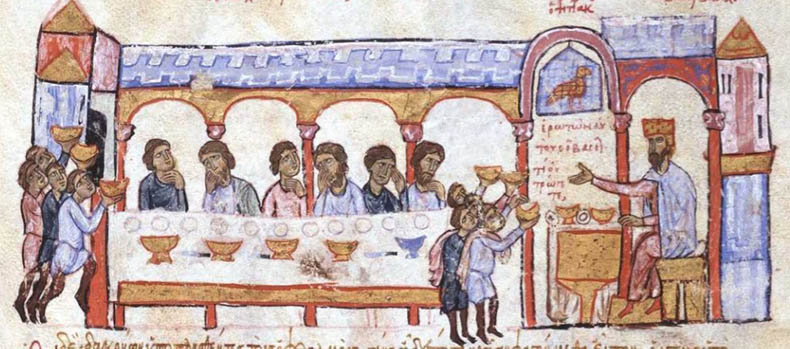

Alas for Basil, his favorite Constantine died and he was compelled to release Leo from prison due to public pressure and a guilty conscience. Basil was hosting a banquet in the palace for a group of senators. During the dinner a palace parrot - a favorite and very popular bird - who had been kept in a cage near Basil started screeching "Poor Leo, Poor Leo, let him go", over and over again! No one knew where the parrot learned to say it and his words were considered an omen. The senators pleaded with Basil to take pity on Leo. Basil released Leo in June and three months later in, September 866, Basil was dead! Happy Leo, poor Basil. There is no record of what happened to the parrot, one can hope Leo rewarded him for his intervention on Leo's behalf when he became sole emperor. Below is a manuscript illustration of the incident of the parrot, probably a green Indian ringneck parakeet, which was very popular in Byzantium as a pet. They were recognized for their ability to clearly mimic human language were admired for their colors and charming disposition, but the church discouraged excessive attention being given to pets like birds. Clement of Alexandria rebuked people who kept parrots, apes, and peacocks to amuse them at dinner, instead of providing for the poor. On can only imagine Imperial dinners with apes!

In the same year Leo had his eunuch brother, the 19 year old Stephen, made Patriarch. He served for seven years and seems to have been a pious, if ridiculously youthful prelate. Leo deposed the scholar-patriarch Photius when he had his brother elevated. Photios had been Leo's tutor and Leo had no love for him. Photius later became a saint in the Orthodox church.

Leo had been married when he was 16 to Theopano, a beautiful but highly religious and frigid girl. She had been selected by his mother in a bridal competition among potential girls. Leo hated Theopano. When his mother died he took up publicly with a mistress, Zoe Zaoutzaina. Through a series of marriages that ended in deaths he had a son with another mistress named, Zoe - whose nickname was Dark Eyes. She bore him a son - his first surviving boy - and this began Leo's campaign to having his marriage to Zoe recognized by the church and his son made his heir. Eventually Leo's marriage was recognized and his son was made legitimate in time to succeed him on the throne as Constantine VII Porphyrogennetos - "Born in the Purple Chamber".

Indeed, Leo had a very bad relationship with the church. He considered himself a great theologian and preacher and personally delivered sermons in church. He took Muslim ambassadors through Hagia Sophia and order the clergy to show them the sacred vestments, vessels and crosses from the Treasury. The Muslim ambassadors had come from the Emirate of Tarsus. The son of the emir was with them. There was talk that the emir was considering converting to Christianity and he was given a grand tour of Hagia Sophia in order to impress him with the superiority of the Christian faith. Choirs were chanting and fragrant incense was burnt to enhance the other-worldliness of the church. The church had been decorated with garlands of flowers and the floors were strewn with fragrant rosemary, myrtle and grape leaves and it had been washed with rosewater. The emir's son was forced to return to his father and did not convert. Below is an illustration of Leo VI showing the sacred treasures to the Muslim visitors in Hagia Sophia.

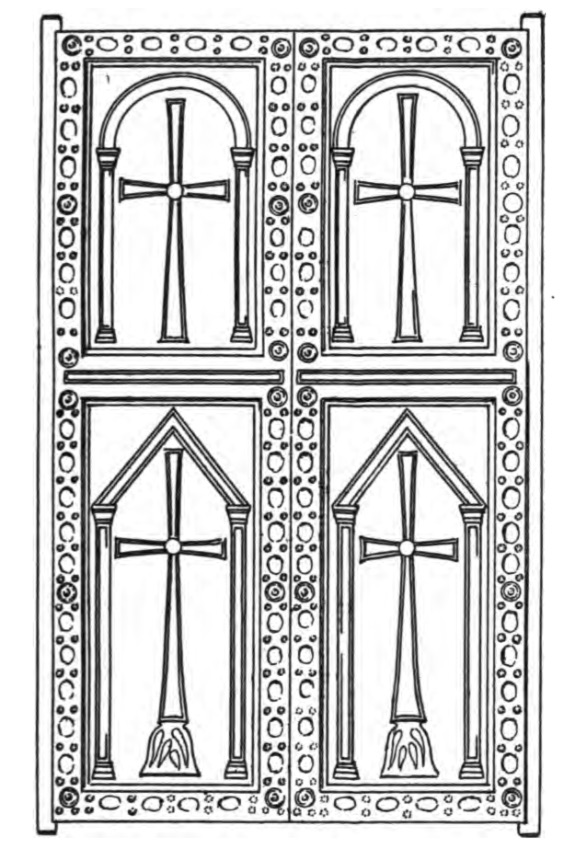

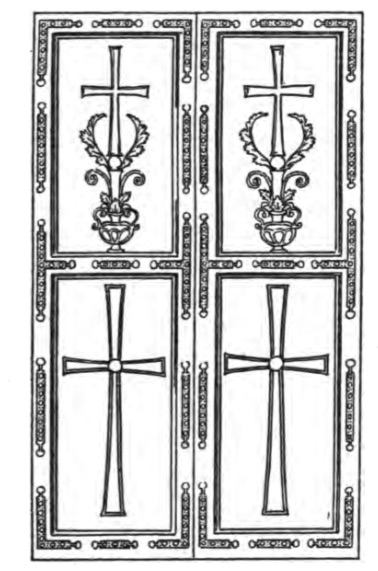

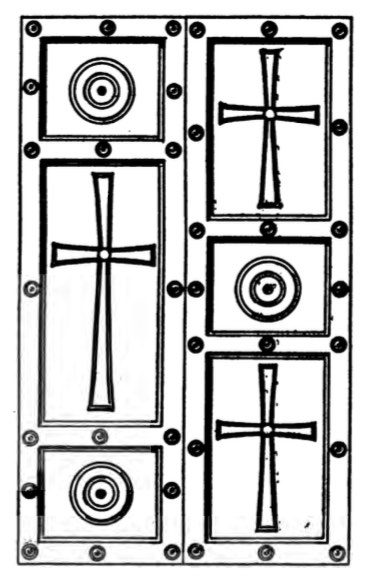

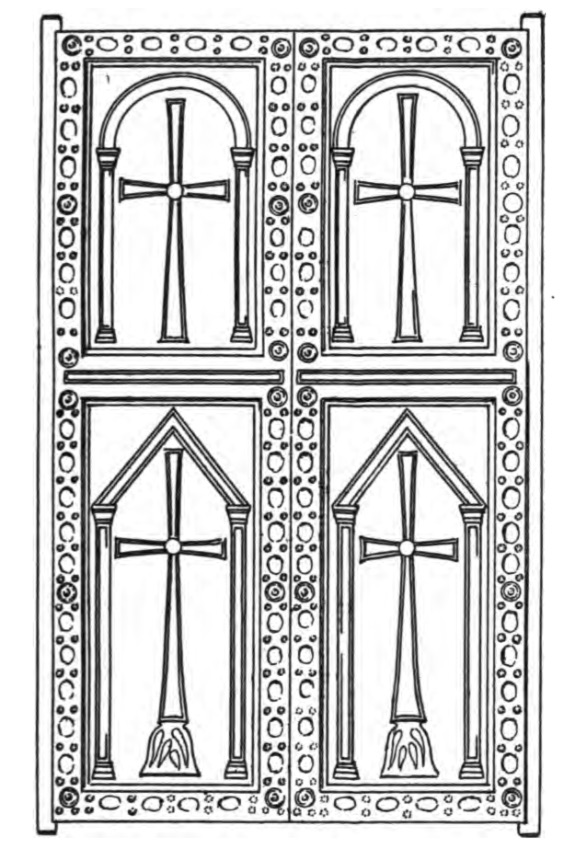

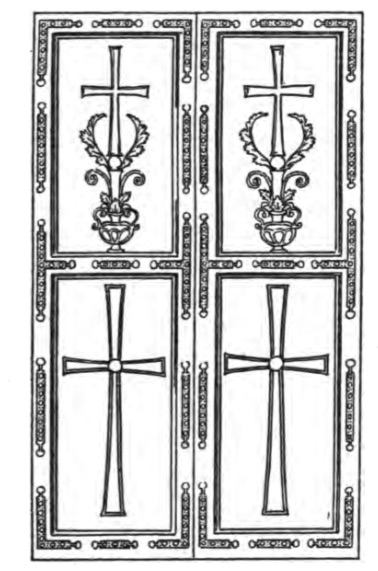

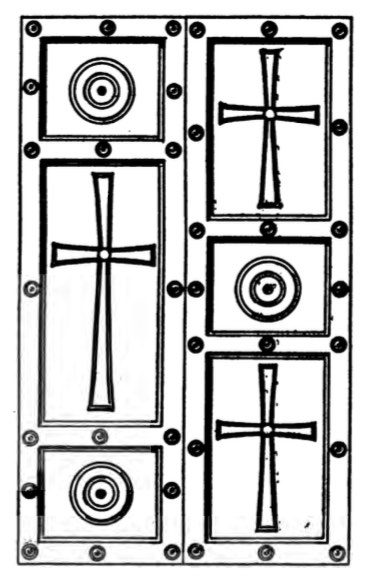

All the doors opening into or from the narthex, with one exception, are cased in leaded brass on a wood foundation about five inches thick, formed into panels. They are all hung in two leaves, and the back edges against the frame are rounded continuing top and bottom as pivots on which they revolve. The

nine doors entering the church are comparatively plain, each leaf being divided into three panels.

The center door was called the Royal Door and only the Emperor could pass through it on special days. At the ritual entrance of the Emperor to Hagia Sophia, holding a large candle, he would bow three times before this door, while choirs chanted. It's huge and massive planks were said to be wood from Noah's Ark, a story first recorded in the 9th century. The Partia Constantinopoleos informs us: “In the second narthex the doors were made of ivory (three to the right, three to the left, and between them) three other doors: two of the middle size, and between them there was the very big one of gilded silver. All the doors were gilded. Inside these doors instead of normal wood there was the Wood of the Ark”. Alas, the wood in the doors did not come from the the Great Ark. All of the many varieties of wood used in Constantinople for furniture and construction came from the Pontic forests of Anatolia, which produced very long logs and timber, or from the forests of the Haemus/Balkan mountains which come down to the sea north of Messembria. The Pontic Forests along the Black Sea contain Nordmann Fir, Oriental Beech, Sweet chestnut, Black Alder and Scotch Pine. Nordmann Fir grows up to 78m (255 ft) in height there. It is the tallest tree that grows in Europe. They would have been used for roofing wide spaces like basilica churches. As long as Byzantium controlled the Pontic Coast of northern Anatolia they had access to all of the wood they could possibly want and it was easy to transport. Today the Nordmann Fir, which is evergreen and has soft needles that do not drop, is widely grown as a Christmas tree in Europe and North America.

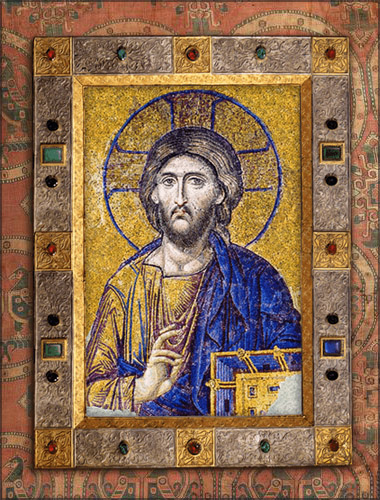

As described in the Partia the door was covered by sheets of silver-gilt. It was secured by a big and impressive silver lock. In Byzantine times the door was also known as the Silver Gates as well as the Beautiful Gates. On either side of the door hung an icon of the Savior and one Mary of Egypt and the Theotokos, brought here from the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem. Markings 7ft from the floor show where the icons were placed. The door was also known as Door of Repentance, above in the arch is a mosaic of the Byzantine Emperor Leo the Wise. He ran afoul of the Church by marrying too many times, once to the extraordinary beauty Zoe Karbonopsina "Dark-Eyes", who bore him a son and heir. On two occasions (Christmas 906 and Epiphany, 6 January 907) the emperor arrived in procession with the senate at this very door - only to be denied entry by the Patriarch Nicholas for his forth illegal marriage to Zoe. For this he was compelled to make penance for the sin of marrying too many times. In the mosaic you can see Leo prostrated before Christ. Although he was forbidden to enter the nave of the church, Leo was allowed to enter the church through the right aisle to walk to the private Imperial changing room - the Metatorian - at the end of the aisle where he could watch and listen to the liturgy in disgrace. Leo had dinner with the Patriarch and a bunch of bishops to plead his case for the recognition of his marriage and the legitimacy of his son. This dinner might have been held in the changing room, emperors had breakfast there after services. Was his parrot there to add his voice in support of Leo's case? "Poor Leo, Poor Leo"? After dinner he was able to drag the clergymen to his private quarters in the palace, where he showed his son to them and shed tears for the tragedy of his marriages - especially that to Theopano. In time the crisis was resolved and Leo was allowed to enter the nave again and receive the sacrament.

As described in the Partia the door was covered by sheets of silver-gilt. It was secured by a big and impressive silver lock. In Byzantine times the door was also known as the Silver Gates as well as the Beautiful Gates. On either side of the door hung an icon of the Savior and one Mary of Egypt and the Theotokos, brought here from the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem. Markings 7ft from the floor show where the icons were placed. The door was also known as Door of Repentance, above in the arch is a mosaic of the Byzantine Emperor Leo the Wise. He ran afoul of the Church by marrying too many times, once to the extraordinary beauty Zoe Karbonopsina "Dark-Eyes", who bore him a son and heir. On two occasions (Christmas 906 and Epiphany, 6 January 907) the emperor arrived in procession with the senate at this very door - only to be denied entry by the Patriarch Nicholas for his forth illegal marriage to Zoe. For this he was compelled to make penance for the sin of marrying too many times. In the mosaic you can see Leo prostrated before Christ. Although he was forbidden to enter the nave of the church, Leo was allowed to enter the church through the right aisle to walk to the private Imperial changing room - the Metatorian - at the end of the aisle where he could watch and listen to the liturgy in disgrace. Leo had dinner with the Patriarch and a bunch of bishops to plead his case for the recognition of his marriage and the legitimacy of his son. This dinner might have been held in the changing room, emperors had breakfast there after services. Was his parrot there to add his voice in support of Leo's case? "Poor Leo, Poor Leo"? After dinner he was able to drag the clergymen to his private quarters in the palace, where he showed his son to them and shed tears for the tragedy of his marriages - especially that to Theopano. In time the crisis was resolved and Leo was allowed to enter the nave again and receive the sacrament.

The door has a leaded brass frame that dates from either the 6th century or the ninth century. Based on the style of the text, most recent scholarship supports a later date. Along the top are a series of hooks in the shape of fingers The brass has the same fine ornamentation in its borders as the other doors in Hagia Sophia. I don't know if the brass frame was ever gilded. I think not, since the only gilding method that could be oil based one. Brass can be kept polished to a very fine gold-like finish, let's assume that's what was done.

The door has a leaded brass frame that dates from either the 6th century or the ninth century. Based on the style of the text, most recent scholarship supports a later date. Along the top are a series of hooks in the shape of fingers The brass has the same fine ornamentation in its borders as the other doors in Hagia Sophia. I don't know if the brass frame was ever gilded. I think not, since the only gilding method that could be oil based one. Brass can be kept polished to a very fine gold-like finish, let's assume that's what was done.

The two doors on the sides of the Royal Doors are carved of green Verde Antico marble from Thessaly. There were several Imperial quarries of this stone near Larissa. This stone was extremely popular in Byzantine times. It is used through Hagia Sophia for columns, architectural items and revetment. You can learn more about Verde Antico by visiting this page.

Anyone who wanted to enter Hagia Sophia had to have recently been to confession to be ritually pure. I don't think this could have been checked because there would have been thousands of visitors every hour of the day. If you could not find a priest you could confess your sins to the icon of Christ and receive forgiveness through Him. This would have been a fast thing anyone could do quickly and privately.

In 1453, when the Muslim army hacked its way into Hagia Sophia it is unlikely they could have battered this door down. It was still probably covered in metal plates and the wood (probably Oak) was too thick. So is the wood the original wood; how old is it? Some experts have speculated that it must have been replaced during the mid-19th century restoration by the Fosatti brothers. It would be easy to test the wood to determine its age. Maybe this has already been done.

All of the doors of the inner and outer narthexes are made of leaded brass. Constantinople was the main source for leaded brass doors which were ornamented with inlaid gold and silver. There are many examples in Italy that still survive, including the doors of Saint Paul Outside the walls in Rome. The doors were transported in parts by ship and assembled on site.

The inner and outer narthexes are very irregular in design and execution. The doorways don't align and are different sizes. All of the doors have different profiles and lintels. Those lintels might have been carved on the spot, after the marble block had been inserted into the wall. There is no explanation for why they are different. Had they all been carved in advance in the marble yard they could have been made the right sizes with similar profiles. There must have been different teams working on the doors who do not seem to have been coordinating their work so that they would match. This spontaneousness is one of the things that endears some people to Hagia Sophia and drives others nuts.

The inner and outer narthexes are very irregular in design and execution. The doorways don't align and are different sizes. All of the doors have different profiles and lintels. Those lintels might have been carved on the spot, after the marble block had been inserted into the wall. There is no explanation for why they are different. Had they all been carved in advance in the marble yard they could have been made the right sizes with similar profiles. There must have been different teams working on the doors who do not seem to have been coordinating their work so that they would match. This spontaneousness is one of the things that endears some people to Hagia Sophia and drives others nuts.

Recently all of the imperfections in design - especially marble carving - have been blamed on the great darkening of the Earth that took place at the same time Hagia Sophia was being built. The darkening was caused by an volcanic eruption and lasted several years. There was no more than 4 hours of dim light a day during this darkening. From tree rings it has been proven that It occurred in 536-537 - just as Hagia Sophia was being finished (it was opened officially in December 537.

Underneath the floor you can see a long vaulted passage. This passage is forgotten and 'rediscovered' every 20 years or so. It is low and you can't stand up in it. This cross section, drawn by Robert Van Nice, shows the upper West Gallery.

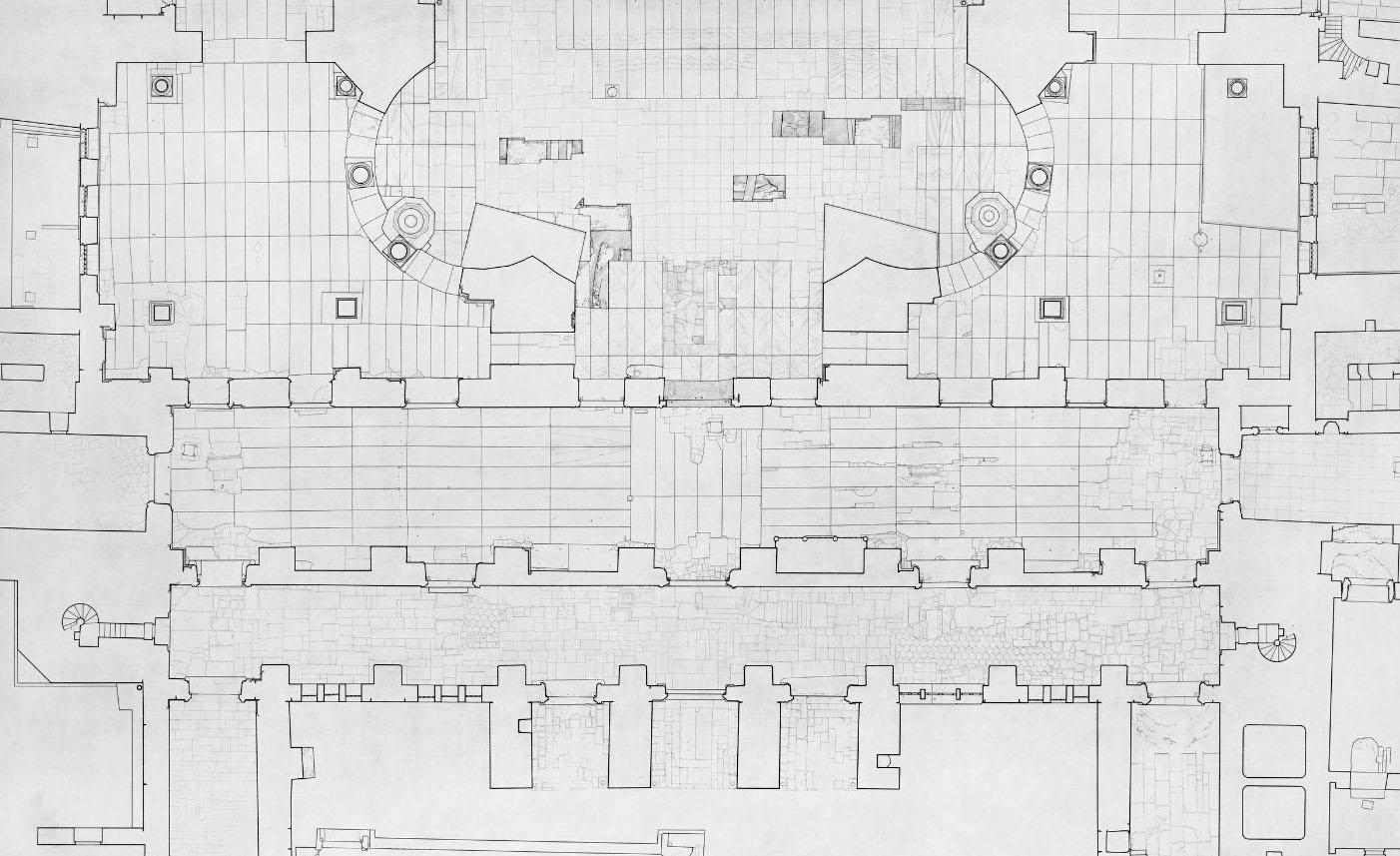

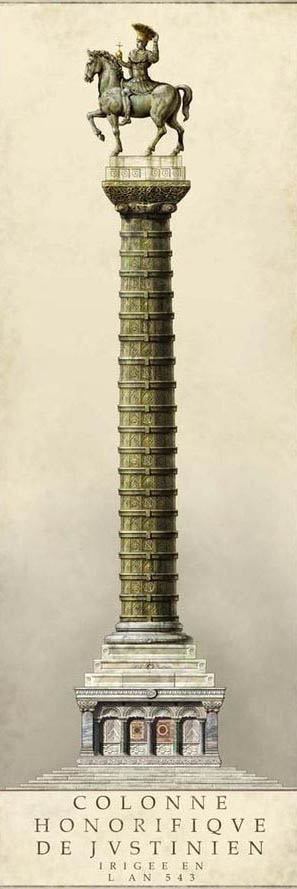

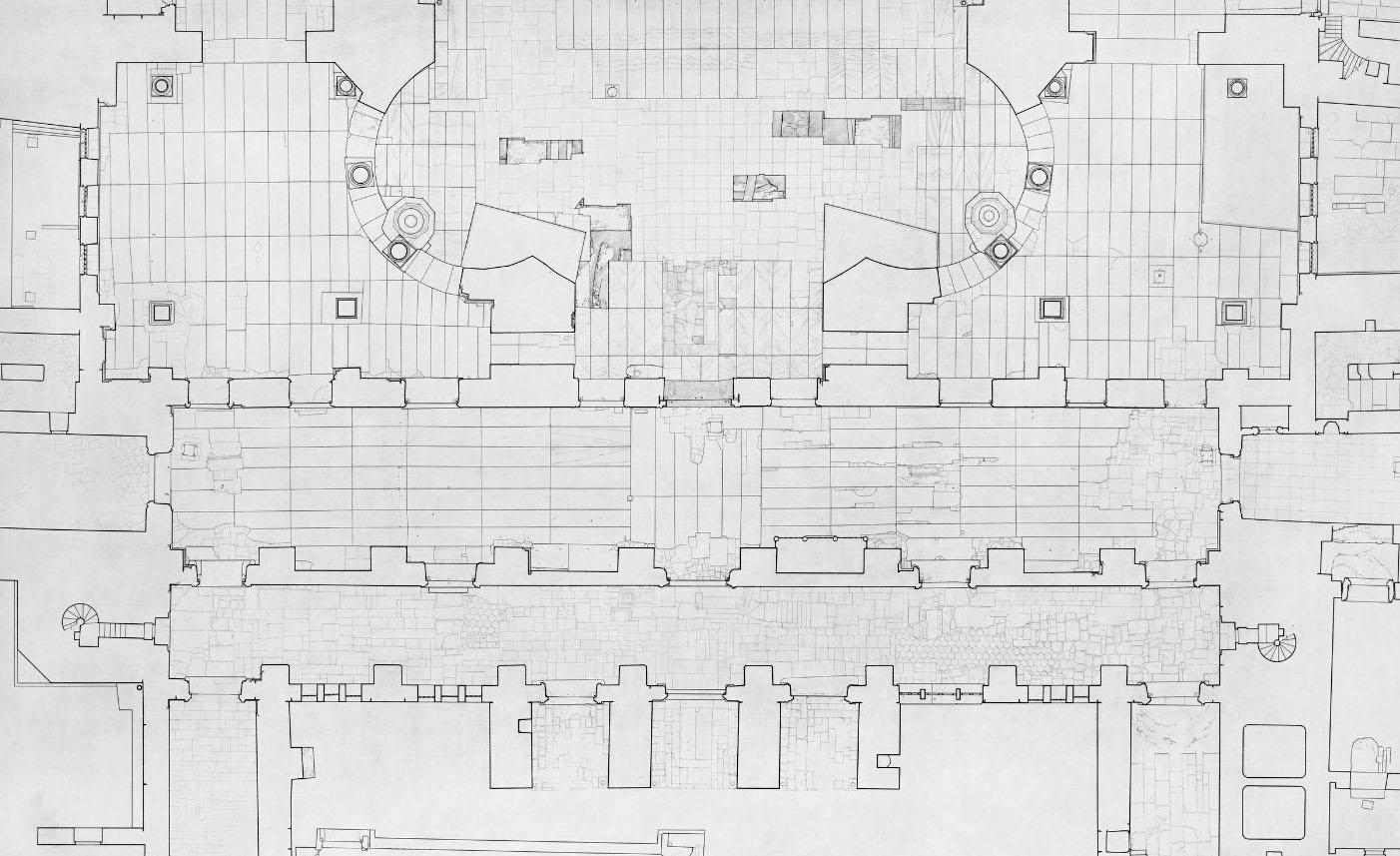

Here is a floor plan of the narthexes. The inner narthex has nine doors and the outer five. Only the center door lines up. You can see the inner narthex still has most of its floor of white Proconnesian marble in slabs that match the paving of the nave. The other narthex has been relaid with a a hodge-podge of marble bits and even terracotta tiles. It's a mess! The outer narthex opened onto an atrium with a fountain. On Sundays free bread was distributed to the elderly poor alongside it. The atrium had a colonnade of columns and piers. The columns probably were pinkish troad granite from quarries near the city. The atrium was dismantled in the 19th century for its building parts. They columns were needed for Ottoman building projects. Over the center flying buttresses was a belfry for bells. You can see an image below. In Byzantine times the main entrance to Hagia Sophia shifted to the Southern Vestibule which opened onto the Augusteon, a forum which became the forecourt of the church. if was full of ancient statues and a colossal column with a statue of Justinian on horseback set on the top. The Augusteon was full of shops and restaurants that catered to visitors to Hagia Sophia. Their rents supported the operation of the church.

The vaults of the inner narthex are encrusted with original gold and glass mosaic from the time of Justinian. It seems the original Hagia Sophia had no figurative mosaics - just decorative patterns, crosses and acanthus. The inner narthex was used for public meetings. The clerical court of Hagia Sophia, which heard claims of sanctuary in murder cases, was seated here. Pilgrims entered the north aisle of Hagia Sophia through the last door of the inner narthex. The door frame was inset with a silver cross, which was worn down by millions of pilgrims kissing it before entering, but you can still see where it was. Anyone who didn't kiss this cross would be assumed not be a Christian. Leo's Muslim visitors to Hagia Sophia would not have kissed it - or any other cross they saw or were offered during the show he put on for them. One they were in pilgrims moved clockwise through the north aisle, the eastern part of the nave, then the Chapel of the Holy Well and finally the north aisle - venerating the icons and relics along the way.

The vaults of the inner narthex are encrusted with original gold and glass mosaic from the time of Justinian. It seems the original Hagia Sophia had no figurative mosaics - just decorative patterns, crosses and acanthus. The inner narthex was used for public meetings. The clerical court of Hagia Sophia, which heard claims of sanctuary in murder cases, was seated here. Pilgrims entered the north aisle of Hagia Sophia through the last door of the inner narthex. The door frame was inset with a silver cross, which was worn down by millions of pilgrims kissing it before entering, but you can still see where it was. Anyone who didn't kiss this cross would be assumed not be a Christian. Leo's Muslim visitors to Hagia Sophia would not have kissed it - or any other cross they saw or were offered during the show he put on for them. One they were in pilgrims moved clockwise through the north aisle, the eastern part of the nave, then the Chapel of the Holy Well and finally the north aisle - venerating the icons and relics along the way.

This is a great picture of the inner narthex that shows the condition of the floors and the huge slabs of marble that were used. There are a couple of pictures of revetment in the narthex above. the revetment was laid irregularly - some of the transverse bands of Verde Antico don't line up - the second one up is wider on the right than the left. It changes at the third door on the left in the center. Many of the panels of above the doors don't line up perfectly. Those big gray (they are really black) and white panels need cleaning and polishing - they are Celticum marble from St. Girons Hèche and Hèchettes, in Hautes-Pyrénées, France. The broad framing bands are pale yellow giallo antico, which was used in the narthex instead of golden onyx. The inner narthex was probably the first part of Hagia Sophia to receive its revetment. The giallo antico seems to have run out early on. In the nave golden onyx, which is Alabastro fiorito, from the Pamukkale area in Denizli, Turkey was used. This onyx is actually a banded travertine. Pamukkale is the site of the ancient city of Hierapolis, and travertine, deposited by hot springs, forms huge terraces from which stone was extracted in ancient times, and is still quarried to this day. I have a special page on the revetment of Hagia Sophia which you can read here.

This is a great picture of the inner narthex that shows the condition of the floors and the huge slabs of marble that were used. There are a couple of pictures of revetment in the narthex above. the revetment was laid irregularly - some of the transverse bands of Verde Antico don't line up - the second one up is wider on the right than the left. It changes at the third door on the left in the center. Many of the panels of above the doors don't line up perfectly. Those big gray (they are really black) and white panels need cleaning and polishing - they are Celticum marble from St. Girons Hèche and Hèchettes, in Hautes-Pyrénées, France. The broad framing bands are pale yellow giallo antico, which was used in the narthex instead of golden onyx. The inner narthex was probably the first part of Hagia Sophia to receive its revetment. The giallo antico seems to have run out early on. In the nave golden onyx, which is Alabastro fiorito, from the Pamukkale area in Denizli, Turkey was used. This onyx is actually a banded travertine. Pamukkale is the site of the ancient city of Hierapolis, and travertine, deposited by hot springs, forms huge terraces from which stone was extracted in ancient times, and is still quarried to this day. I have a special page on the revetment of Hagia Sophia which you can read here.

The outer narthex was stripped of its marble revetment, mosaics and plastered in Ottoman times. Since Hagia Sophia became a museum the plaster has been removed leaving the exposed brick. The hooks above the doors were for draperies. In this image (thank you again Ken Grub) you can see terracotta tiles in the lower left. All of the bits of marble in the floor came from other parts of Hagia Sophia and many bear markings showing where columns and railings were inserted.

The outer narthex was stripped of its marble revetment, mosaics and plastered in Ottoman times. Since Hagia Sophia became a museum the plaster has been removed leaving the exposed brick. The hooks above the doors were for draperies. In this image (thank you again Ken Grub) you can see terracotta tiles in the lower left. All of the bits of marble in the floor came from other parts of Hagia Sophia and many bear markings showing where columns and railings were inserted.

The outer narthex has a number of Byzantine marble remnants on display. Here is an interesting basin carved with serpents. Most of the Byzantine leftovers are in the sculpture garden outside the church, slowly dissolving and loosing them features in the acid rain.

The outer narthex has a number of Byzantine marble remnants on display. Here is an interesting basin carved with serpents. Most of the Byzantine leftovers are in the sculpture garden outside the church, slowly dissolving and loosing them features in the acid rain.

Above is the tomb of Eirene in Verde Antica Serpentinite Breccia, which was formerly in the Pantokrator Monastery. Until at least the late 19th century it was seen outside the former church, where it had been moved and was used as a fountain. In 1960 it was moved to Hagia Sophia where you can see it in the outer narthex. It was carved with simple crosses in circles, which have almost vanished with time. There are 14 marble tombs preserved in Hagia Sophia today, most of them are in the garden.

Here is a image from Ottoman times. All of the doors were covered like this with Islamic inscriptions using the original Byzantine hooks. In Byzantine times the draperies were parted in the middle and were made of heavy silk woven with patterns in bands. They could also have had gold embroideries. Here you can see how the marble threshold has been worn away by hundreds of years of feet.

Here is a image from Ottoman times. All of the doors were covered like this with Islamic inscriptions using the original Byzantine hooks. In Byzantine times the draperies were parted in the middle and were made of heavy silk woven with patterns in bands. They could also have had gold embroideries. Here you can see how the marble threshold has been worn away by hundreds of years of feet.

As described in the Partia the door was covered by sheets of silver-gilt. It was secured by a big and impressive silver lock. In Byzantine times the door was also known as the Silver Gates as well as the Beautiful Gates. On either side of the door hung an icon of the Savior and one Mary of Egypt and the Theotokos, brought here from the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem. Markings 7ft from the floor show where the icons were placed. The door was also known as Door of Repentance, above in the arch is a mosaic of the Byzantine Emperor Leo the Wise. He ran afoul of the Church by marrying too many times, once to the extraordinary beauty Zoe Karbonopsina "Dark-Eyes", who bore him a son and heir. On two occasions (Christmas 906 and Epiphany, 6 January 907) the emperor arrived in procession with the senate at this very door - only to be denied entry by the Patriarch Nicholas for his forth illegal marriage to Zoe. For this he was compelled to make penance for the sin of marrying too many times. In the mosaic you can see Leo prostrated before Christ. Although he was forbidden to enter the nave of the church, Leo was allowed to enter the church through the right aisle to walk to the private Imperial changing room - the Metatorian - at the end of the aisle where he could watch and listen to the liturgy in disgrace. Leo had dinner with the Patriarch and a bunch of bishops to plead his case for the recognition of his marriage and the legitimacy of his son. This dinner might have been held in the changing room, emperors had breakfast there after services. Was his parrot there to add his voice in support of Leo's case? "Poor Leo, Poor Leo"? After dinner he was able to drag the clergymen to his private quarters in the palace, where he showed his son to them and shed tears for the tragedy of his marriages - especially that to Theopano. In time the crisis was resolved and Leo was allowed to enter the nave again and receive the sacrament.

As described in the Partia the door was covered by sheets of silver-gilt. It was secured by a big and impressive silver lock. In Byzantine times the door was also known as the Silver Gates as well as the Beautiful Gates. On either side of the door hung an icon of the Savior and one Mary of Egypt and the Theotokos, brought here from the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem. Markings 7ft from the floor show where the icons were placed. The door was also known as Door of Repentance, above in the arch is a mosaic of the Byzantine Emperor Leo the Wise. He ran afoul of the Church by marrying too many times, once to the extraordinary beauty Zoe Karbonopsina "Dark-Eyes", who bore him a son and heir. On two occasions (Christmas 906 and Epiphany, 6 January 907) the emperor arrived in procession with the senate at this very door - only to be denied entry by the Patriarch Nicholas for his forth illegal marriage to Zoe. For this he was compelled to make penance for the sin of marrying too many times. In the mosaic you can see Leo prostrated before Christ. Although he was forbidden to enter the nave of the church, Leo was allowed to enter the church through the right aisle to walk to the private Imperial changing room - the Metatorian - at the end of the aisle where he could watch and listen to the liturgy in disgrace. Leo had dinner with the Patriarch and a bunch of bishops to plead his case for the recognition of his marriage and the legitimacy of his son. This dinner might have been held in the changing room, emperors had breakfast there after services. Was his parrot there to add his voice in support of Leo's case? "Poor Leo, Poor Leo"? After dinner he was able to drag the clergymen to his private quarters in the palace, where he showed his son to them and shed tears for the tragedy of his marriages - especially that to Theopano. In time the crisis was resolved and Leo was allowed to enter the nave again and receive the sacrament. The door has a leaded brass frame that dates from either the 6th century or the ninth century. Based on the style of the text, most recent scholarship supports a later date. Along the top are a series of hooks in the shape of fingers The brass has the same fine ornamentation in its borders as the other doors in Hagia Sophia. I don't know if the brass frame was ever gilded. I think not, since the only gilding method that could be oil based one. Brass can be kept polished to a very fine gold-like finish, let's assume that's what was done.

The door has a leaded brass frame that dates from either the 6th century or the ninth century. Based on the style of the text, most recent scholarship supports a later date. Along the top are a series of hooks in the shape of fingers The brass has the same fine ornamentation in its borders as the other doors in Hagia Sophia. I don't know if the brass frame was ever gilded. I think not, since the only gilding method that could be oil based one. Brass can be kept polished to a very fine gold-like finish, let's assume that's what was done. The inner and outer narthexes are very irregular in design and execution. The doorways don't align and are different sizes. All of the doors have different profiles and lintels. Those lintels might have been carved on the spot, after the marble block had been inserted into the wall. There is no explanation for why they are different. Had they all been carved in advance in the marble yard they could have been made the right sizes with similar profiles. There must have been different teams working on the doors who do not seem to have been coordinating their work so that they would match. This spontaneousness is one of the things that endears some people to Hagia Sophia and drives others nuts.

The inner and outer narthexes are very irregular in design and execution. The doorways don't align and are different sizes. All of the doors have different profiles and lintels. Those lintels might have been carved on the spot, after the marble block had been inserted into the wall. There is no explanation for why they are different. Had they all been carved in advance in the marble yard they could have been made the right sizes with similar profiles. There must have been different teams working on the doors who do not seem to have been coordinating their work so that they would match. This spontaneousness is one of the things that endears some people to Hagia Sophia and drives others nuts.

The vaults of the inner narthex are encrusted with original gold and glass mosaic from the time of Justinian. It seems the original Hagia Sophia had no figurative mosaics - just decorative patterns, crosses and acanthus. The inner narthex was used for public meetings. The clerical court of Hagia Sophia, which heard claims of sanctuary in murder cases, was seated here. Pilgrims entered the north aisle of Hagia Sophia through the last door of the inner narthex. The door frame was inset with a silver cross, which was worn down by millions of pilgrims kissing it before entering, but you can still see where it was. Anyone who didn't kiss this cross would be assumed not be a Christian. Leo's Muslim visitors to Hagia Sophia would not have kissed it - or any other cross they saw or were offered during the show he put on for them. One they were in pilgrims moved clockwise through the north aisle, the eastern part of the nave, then the Chapel of the Holy Well and finally the north aisle - venerating the icons and relics along the way.

The vaults of the inner narthex are encrusted with original gold and glass mosaic from the time of Justinian. It seems the original Hagia Sophia had no figurative mosaics - just decorative patterns, crosses and acanthus. The inner narthex was used for public meetings. The clerical court of Hagia Sophia, which heard claims of sanctuary in murder cases, was seated here. Pilgrims entered the north aisle of Hagia Sophia through the last door of the inner narthex. The door frame was inset with a silver cross, which was worn down by millions of pilgrims kissing it before entering, but you can still see where it was. Anyone who didn't kiss this cross would be assumed not be a Christian. Leo's Muslim visitors to Hagia Sophia would not have kissed it - or any other cross they saw or were offered during the show he put on for them. One they were in pilgrims moved clockwise through the north aisle, the eastern part of the nave, then the Chapel of the Holy Well and finally the north aisle - venerating the icons and relics along the way. This is a great picture of the inner narthex that shows the condition of the floors and the huge slabs of marble that were used. There are a couple of pictures of revetment in the narthex above. the revetment was laid irregularly - some of the transverse bands of Verde Antico don't line up - the second one up is wider on the right than the left. It changes at the third door on the left in the center. Many of the panels of above the doors don't line up perfectly. Those big gray (they are really black) and white panels need cleaning and polishing - they are Celticum marble from St. Girons Hèche and Hèchettes, in Hautes-Pyrénées, France. The broad framing bands are pale yellow giallo antico, which was used in the narthex instead of golden onyx. The inner narthex was probably the first part of Hagia Sophia to receive its revetment. The giallo antico seems to have run out early on. In the nave golden onyx, which is Alabastro fiorito, from the Pamukkale area in Denizli, Turkey was used. This onyx is actually a banded travertine. Pamukkale is the site of the ancient city of Hierapolis, and travertine, deposited by hot springs, forms huge terraces from which stone was extracted in ancient times, and is still quarried to this day. I have a special page on the revetment of Hagia Sophia

This is a great picture of the inner narthex that shows the condition of the floors and the huge slabs of marble that were used. There are a couple of pictures of revetment in the narthex above. the revetment was laid irregularly - some of the transverse bands of Verde Antico don't line up - the second one up is wider on the right than the left. It changes at the third door on the left in the center. Many of the panels of above the doors don't line up perfectly. Those big gray (they are really black) and white panels need cleaning and polishing - they are Celticum marble from St. Girons Hèche and Hèchettes, in Hautes-Pyrénées, France. The broad framing bands are pale yellow giallo antico, which was used in the narthex instead of golden onyx. The inner narthex was probably the first part of Hagia Sophia to receive its revetment. The giallo antico seems to have run out early on. In the nave golden onyx, which is Alabastro fiorito, from the Pamukkale area in Denizli, Turkey was used. This onyx is actually a banded travertine. Pamukkale is the site of the ancient city of Hierapolis, and travertine, deposited by hot springs, forms huge terraces from which stone was extracted in ancient times, and is still quarried to this day. I have a special page on the revetment of Hagia Sophia  The outer narthex was stripped of its marble revetment, mosaics and plastered in Ottoman times. Since Hagia Sophia became a museum the plaster has been removed leaving the exposed brick. The hooks above the doors were for draperies. In this image (thank you again Ken Grub) you can see terracotta tiles in the lower left. All of the bits of marble in the floor came from other parts of Hagia Sophia and many bear markings showing where columns and railings were inserted.

The outer narthex was stripped of its marble revetment, mosaics and plastered in Ottoman times. Since Hagia Sophia became a museum the plaster has been removed leaving the exposed brick. The hooks above the doors were for draperies. In this image (thank you again Ken Grub) you can see terracotta tiles in the lower left. All of the bits of marble in the floor came from other parts of Hagia Sophia and many bear markings showing where columns and railings were inserted. The outer narthex has a number of Byzantine marble remnants on display. Here is an interesting basin carved with serpents. Most of the Byzantine leftovers are in the sculpture garden outside the church, slowly dissolving and loosing them features in the acid rain.

The outer narthex has a number of Byzantine marble remnants on display. Here is an interesting basin carved with serpents. Most of the Byzantine leftovers are in the sculpture garden outside the church, slowly dissolving and loosing them features in the acid rain.

Here is a image from Ottoman times. All of the doors were covered like this with Islamic inscriptions using the original Byzantine hooks. In Byzantine times the draperies were parted in the middle and were made of heavy silk woven with patterns in bands. They could also have had gold embroideries. Here you can see how the marble threshold has been worn away by hundreds of years of feet.

Here is a image from Ottoman times. All of the doors were covered like this with Islamic inscriptions using the original Byzantine hooks. In Byzantine times the draperies were parted in the middle and were made of heavy silk woven with patterns in bands. They could also have had gold embroideries. Here you can see how the marble threshold has been worn away by hundreds of years of feet.

click here for icons of christ

click here for icons of christ click here for icons of the theotokos

click here for icons of the theotokos click here for icons of angels

click here for icons of angels click here for icons of saints

click here for icons of saints