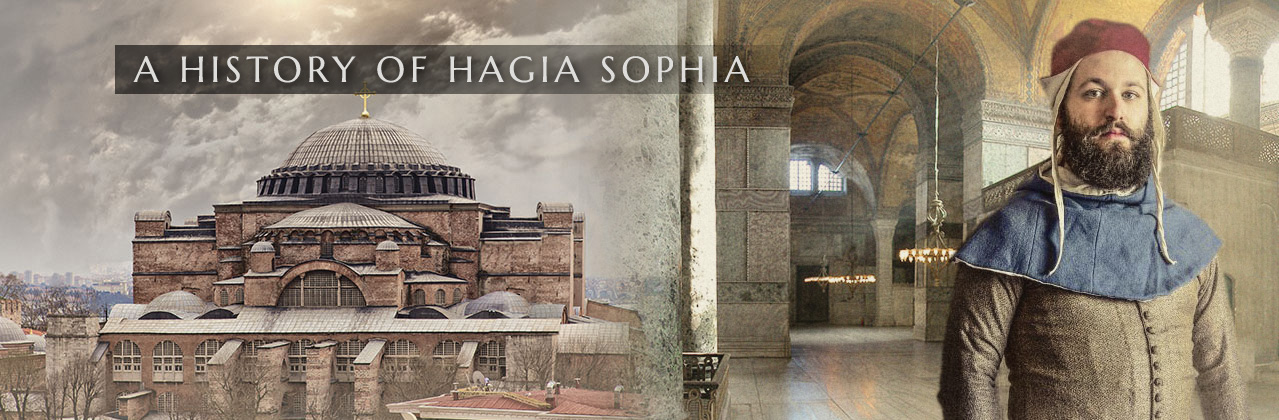

This Varangian Guard is standing outside the Boukoleon Palace, which was decorated with statues of lions and bulls. You can see banners on the right.

This Varangian Guard is standing outside the Boukoleon Palace, which was decorated with statues of lions and bulls. You can see banners on the right. Here we see a guard and court official standing in the courtyard of the Blachernae Palace. He might not be a Varangian because he is not carrying an axe. That strange white hat was actually worn in late Byzantine times. Byzantine peaked hats were widely admired abroad.

Here we see a guard and court official standing in the courtyard of the Blachernae Palace. He might not be a Varangian because he is not carrying an axe. That strange white hat was actually worn in late Byzantine times. Byzantine peaked hats were widely admired abroad. The Chalke Gate of the Great Palace had a high dome over it like this one.

The Chalke Gate of the Great Palace had a high dome over it like this one.

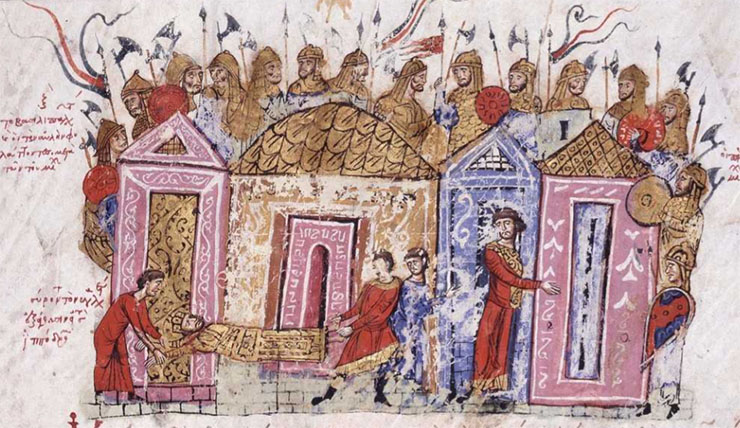

Manuel I Entertains Sultan Kilij Arslan in Constantinople

From O City of Byzantium by Niketas Choniates

Together with the sultan, Manuel entered Constantinople. There he proclaimed a magnificent triumph resplendent with exquisite and precious robes and diverse adornment cunningly wrought. But as the emperor, with members of the bodyguard, the nobility, the imperial retinue, and the sultan (seen below), was about to make his appearance before the citizens to receive their applause, God annulled the splendors of that day The earth shook, and many splendid dwellings collapsed, the atmospheric conditions were violent and unstable, and other such terrors took place so that if one could not pay heed to the triumph, and the mind swooned. The clergy of the holy church, contended (and the emperor himself received their words as evil omens) that God was wroth and that under no circumstances would he tolerate an impious man to show himself and participate in a triumph adorned by all-hallowed furnishings and embellished by the likenesses of the saints and sanctified by the image of Christ. Thus, the triumph was thoughtlessly conceived, and neither did the emperor himself pay adequate attention to it, nor was proper regard paid to custom.

<

Above : Sultan Kilij Arslan

The sultan sojourned with the emperor for some time [80 days] and feasted his eyes on the horse races. Now, in the Hippodrome there was a tower which stood opposite the spectators; beneath it were the starting posts which opened into the racecourse through parallel arches and above were fixed four gilt-bronze horses, their necks somewhat curved as if they eyed each other as they raced round the last lap.

At this time a certain descendant of Agar, who posed as a conjurer but who, as later events were to show, was the most wretched of men and no more than a suicide, ascended, announcing that he would fly through the stadium. He stood on the tower as though at a starting post, dressed in an extremely long, wide white robe, on which twisted withes, gathering the garment all around, made ample folds. It was the Agarene's intention to unfurl the upper garment like the sail of a ship, thus enveloping the wind in its folds. All eyes were turned on him. The spectators smiled and repeatedly shouted, "Fly," and "How long will you keep us in suspense, swaying from the tower to and fro in the wind?" The emperor sent word, attempting to dissuade him from attempting the flight. The sultan, an observer of the unfolding drama, was dubious as to the outcome, he both throbbed with emotion and grinned, elated and at the same time fearful for his compatriot. Snapping at the air frequently and testing the wind, the Agarene mocked the hopes of the spectators. Many times he raised his arms, forming them into wings and beating the air as he poised himself for flight. When a fair and favorable wind arose, he flapped his arms like a bird in the belief that he could walk the air. But he was an even more wretched sky-runner than Ikaros. Instead of taking wing, he plummeted groundward like a solid mass pulled down by gravity. In the end, he plunged to the earth, and his life was snuffed out, his arms and legs and all the bones of his body shattered.

At this time a certain descendant of Agar, who posed as a conjurer but who, as later events were to show, was the most wretched of men and no more than a suicide, ascended, announcing that he would fly through the stadium. He stood on the tower as though at a starting post, dressed in an extremely long, wide white robe, on which twisted withes, gathering the garment all around, made ample folds. It was the Agarene's intention to unfurl the upper garment like the sail of a ship, thus enveloping the wind in its folds. All eyes were turned on him. The spectators smiled and repeatedly shouted, "Fly," and "How long will you keep us in suspense, swaying from the tower to and fro in the wind?" The emperor sent word, attempting to dissuade him from attempting the flight. The sultan, an observer of the unfolding drama, was dubious as to the outcome, he both throbbed with emotion and grinned, elated and at the same time fearful for his compatriot. Snapping at the air frequently and testing the wind, the Agarene mocked the hopes of the spectators. Many times he raised his arms, forming them into wings and beating the air as he poised himself for flight. When a fair and favorable wind arose, he flapped his arms like a bird in the belief that he could walk the air. But he was an even more wretched sky-runner than Ikaros. Instead of taking wing, he plummeted groundward like a solid mass pulled down by gravity. In the end, he plunged to the earth, and his life was snuffed out, his arms and legs and all the bones of his body shattered.

Above: Manuel I Komnenos

This abortive flight was bruited about by the citizens in mockery and ridicule of the Turks in the sultan's retinue. They could not even pass through the agora without being laughed at as the silversmiths made loud noises by striking the iron tools of their benches. When the emperor was informed of these things, he was, in all probability, amused, knowing how the rabble was fond of gossip and play, but he humored the sultan (for as he gradually became aware of the coarse jests, his soul was sorely vexed) and pretended to restrict their freedom of speech.

After the display of admirable munificence, the sultan, who had skimmed off many splendid gifts from the imperial treasuries, before which he stood amazed, wondering if the emperor could possibly possess others of such number and magnitude, returned home laden and rejoicing.

Manuel, who knew that no barbarian is able to resist the temptation of gain, wished to magnify himself and to astound Kilij Arslan with the immense riches of the treasuries which overflowed on all sides of the Roman empire, and thus he displayed all the gifts which he proposed to offer the sultan in one of the palace's splendid men's apartments. These consisted of gold and silver coins, luxuriant raiment, silver beakers, golden Theriklean vessels, linens of the finest weave, and other choice ornaments which were easily procured by the Romans but rare among the barbarians and hardly ever seen by them. On entering the men's apart- ments to which he had summoned the sultan, the emperor inquired if he wished to receive as gifts the contents of the treasury at hand. When the sultan replied that he would take whatever the emperor offered him, the emperor posed a second question, asking if any of the enemies of the Romans could possibly withstand their assault should he pour such treasures on mercenary and native troops. Seized with wonder, and answering that were he the master of such vast sums of money he would have subjugated his enemies long ago, the emperor said, "I present you with all these treasures so that you may know my generosity and munificence and that he who is lord over such wealth is he who grants so much to one man." The sultan was delighted and astonished at the outpouring of money and, blinded by the desire of gain, promised to hand over Sebasteia and its lands to the emperor. Manuel gladly welcomed this promise and agreed to give him more money should he confirm his words by deeds.

Manuel, who knew that no barbarian is able to resist the temptation of gain, wished to magnify himself and to astound Kilij Arslan with the immense riches of the treasuries which overflowed on all sides of the Roman empire, and thus he displayed all the gifts which he proposed to offer the sultan in one of the palace's splendid men's apartments. These consisted of gold and silver coins, luxuriant raiment, silver beakers, golden Theriklean vessels, linens of the finest weave, and other choice ornaments which were easily procured by the Romans but rare among the barbarians and hardly ever seen by them. On entering the men's apart- ments to which he had summoned the sultan, the emperor inquired if he wished to receive as gifts the contents of the treasury at hand. When the sultan replied that he would take whatever the emperor offered him, the emperor posed a second question, asking if any of the enemies of the Romans could possibly withstand their assault should he pour such treasures on mercenary and native troops. Seized with wonder, and answering that were he the master of such vast sums of money he would have subjugated his enemies long ago, the emperor said, "I present you with all these treasures so that you may know my generosity and munificence and that he who is lord over such wealth is he who grants so much to one man." The sultan was delighted and astonished at the outpouring of money and, blinded by the desire of gain, promised to hand over Sebasteia and its lands to the emperor. Manuel gladly welcomed this promise and agreed to give him more money should he confirm his words by deeds.

But the emperor anticipated that the barbarian might not be constant, and, wishing to strike while the iron was hot, acted shortly afterwards according to his promise. He dispatched Constantine Gabras [1162] and sent along with him many other gifts and all manner of armaments, but the sultan, who was a cheat and incapable of speaking the truth, ignored the treaties; on his return to Ikonion, he lay siege to Sebasteia and conquered its subject lands and became master over all.

But the emperor anticipated that the barbarian might not be constant, and, wishing to strike while the iron was hot, acted shortly afterwards according to his promise. He dispatched Constantine Gabras [1162] and sent along with him many other gifts and all manner of armaments, but the sultan, who was a cheat and incapable of speaking the truth, ignored the treaties; on his return to Ikonion, he lay siege to Sebasteia and conquered its subject lands and became master over all.

The sultan had ejected Dhu'l-Nun from his own dominion and made of him a runaway and vagabond while he occupied Kaisareia. Now, he went in pursuit of his remaining countryman; I speak of Yaghi-Basan, whose land he longed for with a passion and after whose life he thirsted. Yaghi-Basan assembled his troops and drew up his forces in battle order, but he was checked in his eagerness by death [1164]. Since Yaghi-Basan's throne was vacant, Dhu'l-Nun secretly entered the satrapy of Amaseia. There he was repulsed and there he was the cause of the death of Yaghi-Basan's wife, who had secretly made Dhu'l-Nun ruler by marrying him; after he had sent for her, the Amaseians rebelled and killed her. Dhu'I-Nun, whom they held in contempt as a ruler, they expelled.

They were not, however, mightier than Kilij Arslan, who proved himself more powerful then they. Just as he had earlier laid claim to Cappadocia, so did he later seize Amaseia, taking advantage of conspicuous good fortune in these affairs. Kilij Arslan was not a physically well-proportioned man but maimed in several of the vital parts of his body. His hands were dislocated at the joints, and he had a slight limp and traveled mostly in a litter. This was the origin of the gibes against him, as a result of which Andronikos later contrived to call him Koutz-Arslan [Halt-Arslan]. Andronikos was fonder of reviling than all other men and devastating in his reproaches, and he was also extremely competent in using the soft words of cunning men to inflict humiliation on those who had committed foul deeds or who had suffered a repulsive physical deformity.

Regardless of his misshapen body (for thus, I deem, nature had molded him), Kilij Arslan had obtained a mighty dominion and was in command of large forces. He did not choose to lead a quiet life, but being by nature an agitator and as turbulent as the gulf of a sea, he harassed the Romans incessantly without a declaration of war and frequently initiated warfare without giving cause, disregarding accords and violating truces, weighing the action he was about to take according to his personal desire. Nor did he hold back from Melitene....

These events took place later. Kilij Arslan had become very powerful. He showed no deference to the emperor, and forgetting the court he had paid when he had been assailed by difficulties, he now required the emperor to pay court to him. Changing with the seasons in the fashion of barbarians, when in need he was inordinately humble but he was high-flying whenever Fortune tipped the scales in his favor. At times, he resorted to unctuous flattery to mollify the emperor and rendered him the esteem due a father; then the emperor, instead of treating him as if he were a wild beast in need of surveillance, honored him by adopting him as a son. In the letters which they exchanged, the emperor was addressed him as father and the sultan as son.But the friendship which they both sanctioned was not genuine, even though they did not dishonor their treaties. The sultan, like a swollen torrent or a serpent which had devoured herbs, deluged and swept away everything before him and often swallowed up our fortresses, spitting out the venom of evil. The emperor, on the other hand, dammed up the main roads and stemmed the rising tide with an unbreakable wall of soldiers, or he lulled the serpent to sleep in peace with the enticement of seductive gold, and as it reared up to strike in pursuit of plunder and coiled its body to crush the army, he soothed and quieted it.

click here for icons of christ

click here for icons of christ click here for icons of the theotokos

click here for icons of the theotokos click here for icons of angels

click here for icons of angels click here for icons of saints

click here for icons of saints