life of Irene and Anna Komnena

The Empresses of Constantinople by Joseph McCabe

The distinguished family of the Comneni has already made its appearance in our narrative. It may be recalled that the last chapter opened with a march of the great provincial nobles upon the capital, and the placing of one of their ablest representatives, Isaac Comnenus, upon the throne. Isaac’s brave life had ended in heroic foolishness. Terrified by an apparition, he embraced the monastic life, ignored the natural desire of his brother John to succeed him, and handed the crown to the Ducas family. During the reign of Eudocia the widow of John Comnenus, Anna, remained in Constantinople to guard the fortunes of her children and eventually to help them to secure the throne. She was a woman of the old Roman build, rather than Byzantine; strong, ambitious, able and despotic. The Cæsar John Ducas looked on her with just suspicion, and accused her of treasonable correspondence with Romanus, when he was struggling to regain his throne. She boldly asserted that the letters were forged, and brandished an image of Christ in the eyes of her judges; but it was expedient to condemn her, and she passed to the melancholy Princes’ Islands.

Michael the Scholar released her as soon as Diogenes was dead, and she returned to Constantinople, to watch and work. She had something of the spirit of her father, who had sent so many of the enemy to the land of shades that he had won the name of Alexius Charon: her mother had been of the great family of the Delasseni. The feebleness of Michael and the insipidity of Nicephorus gave promise of a successful revolution, and Anna and her two sons were shrewd enough not to force the opportunity. The youth had first to learn the mastery of legions and to marry. There were, in fact, four women in Constantinople, all able and ambitious, who sought the throne for their children, and a stupendous amount of intrigue must have been expended. The four were: Anna Comnena, the Empresses Eudocia and Maria, and the wife of Andronicus, son of the Cæsar John Ducas. Andronicus had been fatally wounded in war, and condemned to a lingering death, and his wife pressed the Cæsar to find good alliances for her three daughters. She was one of those virile and beautiful Bulgarian princesses who had found the way to Constantinople, and her eldest daughter, Irene, was now just marriageable.

The wife of Andronicus—we do not know her name—shrewdly concluded that an alliance with the Comneni would best serve her ambition, and she pressed her father-in-law to bring about a marriage between Irene and Alexis, the elder of Anna’s two sons. Alexis was a very promising and successful commander who had recently lost his first wife, and he was not unwilling to wed the fair Irene. Anna Comnena (the younger) describes the pair for us, with her usual verbosity and inexactness, premising that it is beyond the power of art to reproduce their comeliness. Alexis was, it seems, a man of medium height, with very broad shoulders and massive chest, eyes of “terrible splendour,” and a look that was “at once both truculent and bland.” He seems, in fact, to have been a very ordinary young man, with an extraordinary capacity for ruse and intrigue. Irene (Anna’s mother) was, of course, a paragon. Her face was “like the moon,” though not quite so round, and her rosy cheeks and fine blue eyes make the simile somewhat weak; her look, like that of her husband, was “at once sweet and terrible”—the look of “a Minerva of heavenly splendour”—and calm and storm succeeded each other, as on the sea, in her expressive blue eyes;199 her arms and hands were like carven ivory, and her constant gestures extremely graceful. In other words, Irene was a very pretty maiden of thirteen summers at the time, with a large share of the spirit and temper of her Bulgarian mother. These fragments of Anna Comnena’s art may serve to illustrate Gibbon’s indulgent complaint that it is more feminine than the artist herself.

The prospect of so significant a marriage released a fresh flood of intrigue. Anna, the mother of Alexis, remembered that it was John Ducas who had driven her into exile, and would not hear of a match with his daughter-in-law. The Emperor Michael regarded the marriage with distrust; his brother Constantine wanted to marry Alexis to his sister Zoe, Eudocia’s youngest daughter. Through this thicket of obstacles and intrigues the wife of Andronicus fought her way with spirit, and not a little bribery, and the marriage took place. We may assume that this was in the second or third year of Nicephorus, when Irene, who was only fifteen at her coronation, cannot have been more than thirteen or fourteen years old.

The Empress Eudocia had now played her last card, and resigned herself to the life of the monastery; it remained to secure the favour of the lovely Empress Maria. Isaac Comnenus had married her cousin Irene, and had therefore the entrée of her palace. The Slavonian ministers of Nicephorus watched him and his brother with concern, but he won the affection of Maria and, by generous distribution of money, the service of her eunuchs. It was presently announced that the Empress Maria proposed to adopt the successful young commander of the troops, Alexis Comnenus, and when this ceremony had been performed both brothers were at liberty to make lengthy visits to the Empress. It is not difficult to accept the rumour that the relation of Alexis to his “mother” was not entirely filial. Alexis was no ascetic, and he notoriously strayed from his girl-wife. On the other hand, Maria had not shown much delicacy200 in marrying the white-haired sensualist, and the privilege of intimacy with a handsome young general of thirty-seven, her eunuchs being bribed in his and her favour, would be appreciated by her. Her mind was not strong and penetrating enough to see through the trickery of Alexis. He posed as an unambitious general, loyally devoted to her reign and that of her son.

The Emperor Nicephorus probably felt that the young men would await the natural termination of his imperial orgies before seizing the throne, and seems to have regarded them with a certain genial indifference. His ministers, however, knew that their fortunes were ruined if Alexis came to the throne, and they insisted that Nicephorus must name a successor. He chose his nephew, a handsome young noble named Synadenus. Maria was now seriously alarmed, since the accession of Synadenus would mean the monastery for her and, possibly, death for her son, and she allowed the Comneni to witness her tears. They were, they said, devoted to her cause. Nay, they swore on the holy cross that they would acknowledge no rulers but Maria and her son, and she promised, in return, that they should be informed of any step that might be contemplated against them in the palace. I am following, almost entirely, the narrative of Anna Comnena, who enlarges with the most candid pleasure on the deceit of her father, and assures us that her grandmother, Anna, was the soul of the plot. In the palace of the Comneni councils were held daily, and the virile mother directed the movements of her sons. It was a time of great anxiety. One night Nicephorus invited Alexis and Isaac to his banquet, and Anna depicts them nervously glancing round them during the meal for the guards or assassins who might have been summoned to despatch them. But Alexis, a master of ruse and insinuation, won the Emperor, and, when a charge of treason was afterwards brought against him, he easily cleared himself.

At last a message came to the mansion of the Comneni from Maria that Barilas (one of the Slav ministers)201 intended to seize the throne and put out the eyes of Alexis; and it was decided that the time had come for action. Alexis hastily made a tour of the city, persuading some, bribing others, until he had a large number of officers and Senators bound by secret oath to support him. Anna meantime made preparations for the flight of the family during the night. The chief weakness of their position was that a young relative of the Emperor had recently married a young girl of their family, and lived, with a tutor, in an outlying part of their mansion. Anna, regarding the tutor as a spy, locked them in their rooms when they were asleep, and before dawn the whole Comneni family set out on foot to cross the city. At that hour of the night there was little watch in Constantinople, and the nervous band—the mother, the two brothers with their wives, children, and sisters, and a few servants—passed safely and silently down the colonnaded main street as far as the Forum of Constantine, where horses awaited the men. They bade each other farewell in the darkness of the early spring morning, and the brothers galloped to the Blachernæ palace, where they broke into the stables, chose the swiftest horses, hamstrung the rest of the horses, and fled to the army which awaited them in Thrace.

The women and children made their way noiselessly back along the Mese to the cathedral. As they went along the street, the glare of a torch appeared in the distance and they found themselves inconveniently accosted by the tutor spy. Anna kept her presence of mind, however. They had heard, she said, that they were accused of some crime and they were going at once to St Sophia, but as soon as the day broke they would go to the palace to demand justice, and she begged the tutor to go on to the palace to announce their intention. As soon as he had gone, they made for the house of Bishop Nicholas, an annexe of the cathedral into which fugitives were admitted during the night. Rousing the doorkeeper, they announced themselves—they were all heavily veiled—as a party of women who had just landed at the quays from the east, and who would render thanks to the Almighty before repairing to their homes. They were admitted to the church, and, when the officers of the infuriated Emperor arrived, in the early morning, they found that nothing less than a violation of the sanctuary would put the women in the power of Nicephorus. Anna, in fact, clung to the gates of the sanctuary, and exclaimed that the soldiers would have to cut off her hands to remove her from the church, as the Slav ministers threatened. Isaac’s wife Irene, an Iberian princess like her cousin Maria, followed the example of her mother-in-law, and we must imagine the younger Irene and the children standing by, with large and tearful blue eyes, taking their first lesson in Byzantine politics. Nicephorus temporized, and swore to spare their lives. Anna shrewdly stipulated that his oath should be taken on the large cross which the Sybarite Emperor always wore, and, when this had been brought and the oath guaranteed to them, the women passed from the church to the palace-fortress-monastery at Petrion, on the Golden Horn. There they were soon joined by the wife and mother-in-law of George Paleologus, a dashing young commander who had fled with the Comneni, and, by sharing their delicate meats and wines liberally with their jailers, they secured a constant account of the progress of the insurgent brothers.

They heard presently that Alexis and Isaac had safely reached the camp in Thrace, and that it had needed only a little further intrigue on the part of Alexis for the troops to proclaim him Emperor. The next news of importance was that the brothers were encamped with their troops on the higher ground without the city walls, and Nicephorus was distracted and terrified. But we may tell in few words the success of the Comneni. The formidable walls of Constantinople were held by the Varangian guards and Immortals, on whose blind fidelity a ruling (and paying) Emperor could always rely. But the extravagance of Nicephorus had in three years exhausted the treasury—its doors stood open for any man to enter the empty building—the troops were few, and uncertain mercenaries had to be enlisted in the defence. Alexis bribed the German soldiers who held the tower overlooking the Blachernæ gate, and at dawn of Maundy Thursday (1081) his troops poured into the city.

It is one of the few points in favour of Alexis that he here made a very human blunder which might have cost him his life and his ambition. Instead of holding his troops to scatter the guards, who had retreated upon the palace, he rode at once to Petrion to see that the women were safe, and his soldiers—a motley and savage crowd of Thracian and Macedonian mercenaries—spread with fiendish delight over the city, violating nuns in the monasteries and burdening themselves with wine and loot. Paleologus saved them by a bold and crafty seizure of the fleet, cutting off the Emperor’s retreat to Asia. Nicephorus wavered between the vigorous counsels of his ministers and the command of the patriarch that he should abdicate and prevent civil war, but his hesitation enabled the troops to rally, and, with a melancholy farewell to his perfumed baths and opulent banquets, he suffered himself to be shipped to the opposite shore and shaved into a monk.

The Empress Maria is described as trembling in her palace during these critical days of the Holy Week, clinging to her boy Constantine, a pretty seven-year-old lad with curly golden hair and pink and white complexion. Alexis had apparently deceived her, and the Comnenian women would have little consideration for her. For some days, however, she remained in quiet possession of her apartments, and a very keen discussion took place in Constantinople as to the intentions of Alexis. He had put Irene, with her mother and sisters, in the lower and older palace, while he, his mother, brother, and other relations had taken residence in the more important Bucoleon palace, by the water. Did he204 propose to put away his doll-wife and wed the riper beauty? Such things had happened before, and the careful reader of Anna Comnena’s discreet narrative will easily believe that that was the intention, or the disposition, of Alexis. He had treated Irene with coldness and disdain (other chroniclers tell us), and been unfaithful to her. But the little Irene had her party, or Maria had her enemies, and the indecision of Alexis was forced. Paleologus drew up the fleet before Bucoleon. When Alexis sent orders to him that the sailors must not acclaim Irene, he boldly replied that he had “not done all this for Alexis, but for Irene,” and her name rolled from galley to galley. Next the Cæsar John Ducas intervened, and urged Maria to retire; probably he sought favour with Anna. Alexis still hesitated, and Irene was not crowned with him.

Speculation in the city was now seething, but a curious circumstance soon ended the hesitation of Alexis. His mother was devoted to monks generally, and one in particular she so esteemed that she insisted on his being appointed at once patriarch of Constantinople. The actual patriarch, Cosmas, swore that he would not resign in favour of the monk until he had crowned Irene, and Anna had now an additional incentive to press her son. Within a week of the coronation of Alexis the second coronation took place, and Irene began to share the bed and the throne of her husband. The last hope of Maria had gone down before her more virile and older antagonist, and she prepared to retire. Her son Constantine was clothed with the imperial dignity, and an imperial rescript, written in the red or purple ink and signed with the golden seal of the Emperor, guaranteed their safety. With this precious document Maria retired, accompanied by her son, to a somewhat remote palace in the imperial domain, and we may briefly dismiss her from the story. Some years later a pretext was found to remove her from her semi-imperial state and lodge her in a monastery. Her last recorded act is that she205 bethought herself of her first and real husband, who still lived in Constantinople as titular Bishop of Ephesus, and asked and obtained forgiveness.

Alexis now hastened to form about his throne a bulwark of loyal, and richly rewarded, friends, and the Court resounded with sonorous new titles and glittered with new insignia. Another noble, Nicephorus Melissenus, had sought the throne at the same time as Alexis; he was disarmed with the dignity of Cæsar and the remote governorship of Thessalonica. Isaac received the newly created dignity of Sebastocrator; Michael Taroneita, who had married a sister of Alexis, rejoiced in the opulent name of Panhypersebastos; and younger brothers were created Protosebastos and Sebastos.2 When we recollect that the wife of each had a corresponding title and state, we appreciate the splendour of the processions which now constantly fed the enthusiasm of Constantinople.

For a time, however, life in the palace wore a humorously mournful complexion. The appalling outrages of Alexis’s troops had sown bitterness in the minds of the people, and the memory of them had to be obliterated. Any other Emperor would have at once provided a glorious series of chariot races and flung gold in showers from his chariot. Alexis Comnenus found a less expensive device; unless we care to attribute the scheme to his mother, whom he consulted. The new patriarch was humbly begged to impose a penance on all the royal inmates of the palace, and he decided that forty days of fasting and prayer would efface the stain. Alexis himself generously went beyond the letter of the penance; he slept nightly on the ground and wore a hair shirt—and took care that all the citizens knew it. His brothers, his mother and the other women of the family embraced their share of the imposition, and for five or six weeks the Bucoleon palace resembled a monastery.

206 When the period of mourning came to an end Alexis turned to face the numerous and pressing enemies of his Empire, and his mother became the active ruler. Her granddaughter would have us believe that the elder Anna had no ambition to wield power; she was disposed to retire at once into a monastery, and it was only in obedience to a solemn decree of Alexis that she consented to remain in the palace and use the powers of her absent son. But Anna Comnena, the royal historian, possessed in a considerable degree the faculty for ruse and duplicity which distinguished her family, and we have little difficulty in seeing that the older Anna claimed and clung to power. Irene was, of course, still a negligible child. Anna at once set about the restoration of discipline in the palace, which had been so grossly neglected under Nicephorus and Maria. Hours were fixed for meals and prayers and the chanting of hymns, and her table was rarely without the blessing of some priest or monk who would discuss with her the sacred books and theological issues in which she was interested. Sober in diet, liberal to the poor and the Church, awake beyond the hours of most mortals with her long prayers, yet up early in the morning for those imperial duties which the golden bull of her son had laid on her, Anna was at least not unworthy of the power she had intrigued to secure. We must, however, not exaggerate her political influence. A few years later we find Alexis, when he sets out for the field, entrusting the reins of government to his brother, and no doubt Isaac generally controlled the administration.

Of Irene we hear little until the latter part of her husband’s reign, when her services as nurse make him appreciate her value. In spite of the glowing assurances207 of their daughter, we perceive confidently that Irene was slighted, both by the mother and the son, and we shall ultimately find her dismissing him from the world with an assurance of her profound disdain. For two years the chronicles are silent about her, and the one reference to her in twenty years is that she bore children to her spouse. As Christmas approached in 1083 she began to feel the first pangs of travail. Alexis was expected home from his campaign against Robert Guiscard in two days, and Anna Comnena, who is not hypersensitive in her narrative, relates that the young mother signed her body with a cross and said: “Stay where you are, my boy, until your father arrives.” It was not a boy, but the historian herself, who saw the light two days later, and Anna—a fierce and murderous rebel against her brother—asks us to applaud her very early practice of the virtue of obedience.

In view of this silence concerning the Empresses we will hold ourselves dispensed from following Alexis through the campaigns, plots and counter-plots of the next twenty years. Five years were spent in struggle with Robert Guiscard of Italy: five in repelling the wild Patzinaks of Scythia: five more in suppressing conspiracies, or alleged conspiracies, against the throne. It may seem ungenerous to suspect that the hard-working Alexis invented these conspiracies in order to rid his camp and Court of suspected relatives or nobles, but Byzantine historians not obscurely hint such a suspicion. One conspiracy only need be related, since Irene appears on the stage at the time.

Some years after his accession to the throne—the date is uncertain—Alexis consented to the retirement of his mother into the monastery to which, her granddaughter says, her heart had always turned. Very probably Irene, as she grew to womanhood, resented the older woman’s restraint and piety, and insisted on her removal. She died, a nun, a few years afterwards. From that time Alexis drew nearer to Irene, and used to take her with208 him on his campaigns. In 1092 or 1093 there was trouble in Dalmatia, and Irene accompanied her husband and shared his tent in the camp. It was noticed with some alarm by the officers that Nicephorus Diogenes, son of Eudocia, who had received imperial dignity in his infancy and might aspire to regain it, pitched his tent nearer to that of the Emperor than courtesy permitted. Alexis scouted their suspicions, and retired to rest with Irene; but in the middle of the night the maid who was engaged in keeping the flies, or other insects, off the royal sleepers, aroused them with the news that Nicephorus had entered the tent with a drawn sword. One hesitates to say which is the more remarkable: that there should be no guard to the imperial tent, or that Alexis should take no notice of this attempt on his life. A few days later, Anna assures us, Nicephorus renewed the attempt, and was detected with drawn sword near the Emperor’s bath. He was now put to the torture and provided a list of nobles who were obnoxious to the Emperor and were duly punished. It is interesting to find that the ex-Empress Maria was included among the conspirators, and it was possibly on this occasion that she was sent to a nunnery. But the narrated details of the conspiracy are so clumsy, and the issue proved so profitable to Alexis, that historians regard it with grave suspicion.

We come next to the page of Byzantine history which is least unfamiliar to English readers, the page restored to life by Sir Walter Scott in his “Count Robert of Paris.”28 But, profoundly important as the passage of209 the first Crusaders is in Byzantine history and in the biography of Alexis, we have no decent pretext to enlarge on that fascinating episode in a biography of the Empresses. We need say only that Irene trembled with her husband, or more than her husband, at the formidable tide of the invasion. Thinking to secure a few thousand spears to assist him in his warfare with the Turks, Alexis had added a pathetic, if not hypocritical, plea to the eloquence of Peter the Hermit. The response was, in 1096, a devouring and destructive army of locusts: a flood of 300,000 men, women and children, who, before they could be persuaded to cross the straits and leave their bones on the plains of Asia Minor, gravely embarrassed the Byzantine Court. In their train came a more formidable menace: Godfrey of Bouillon, Robert of Flanders, the princes of Western chivalry, with their hawks and hounds and ladies, and their vast hordes of hungry and blustering men-at-arms. Their suspicions, ferocious outbursts, disdain, and greed of wealth, called out every diplomatic resource at the command of Alexis, and few will do more than smile at his duplicity in such circumstances. At one moment, when it was rumoured in their camp without the walls that Alexis had imprisoned some of their leaders, they flung themselves against the city, and a howl of terror was heard from Blachernæ to the Sea of Marmora. How Alexis astutely drew them from the fascinations of his capital, and hovered in their rear, jackal-like, to recover the towns from which they expelled the Turk, and at last brought on a conflict of Latin and Greek, must be read in history. Seven further years of the reign of Alexis and Irene passed in these adventures.

The next decade was full of war against Bohemund, son of his former antagonist Robert Guiscard, and other Crusaders. In the course of the war, in 1105, we again catch a glimpse of Irene, who accompanied Alexis to the camp of Thessalonica. Apropos of the journey her daughter, who was now a mature eyewitness of events, depicts Irene’s character in phrases which we read with some discretion. She was, it seems, so devoted to the reading of sacred books, the conversation of holy men and the discharge of her domestic duties, that she was reluctant to make these journeys; indeed, she could never appear in public without a nervous blush. It is not like the Irene whom we shall know more fully anon. But her husband needed her, and she obeyed. Plotters and conspirators surrounded him, and he suffered acutely from gout in the feet. Of the constant plots Anna offers no explanation; it is not from her that we learn how Alexis so far debased the coinage that his “gold” pieces (almost entirely bronze) were a thing of contempt throughout Europe, how he further oppressed his subjects with monopolies, and how savagely he could at times treat malcontents and heretics. His gout, however, she is eager to explain. It was due, not to any generosity of diet, but to an injury to his knee in early years, aggravated by the stupid “barbarians of the West” (the Crusaders), who kept the sacred Emperor standing for hours to listen to their unceasing torrents of talk. So Irene had to accompany her husband, to chafe his poignant limbs when the gout racked him and to scare away conspirators. She travelled with great modesty, in a litter borne by two mules and so enwrapped with purple that “her divine body was not visible.”

In the following year a conspiracy was “detected” at Constantinople. A wealthy Senator named Solomon and four brothers of Saracenic origin were the chief plotters, and the treasury was enriched by their fortunes. Solomon’s mansion was given to Irene, who is said to have restored it to the wife of the Senator. For once Anna admits that her father could be truculent. Anna was at a window of the palace overlooking the Forum, or the streets near it, when the soldiers and mob passed with the four brother conspirators. They were mounted on oxen, and were derisively adorned with the horns and entrails of oxen by the theatrical folk to whom they had been entrusted before their eyes were put out; from another historian we learn that the hair had already been torn, by means of pitch, from their heads and chins. Anna called her mother, and the two women forced Alexis to put an end to the horrible display and spare the prisoners’ eyes.

A year or two later Irene is said to have saved her husband’s life from fresh conspirators. She had again set out with him for Thessalonica, and, as they camped at Psyllus on the way, a plot was formed to murder Alexis as soon as Irene should return to the city. Alexis would not part with her, and the impatient conspirators threw a parchment in his tent, deriding him for his reluctance to take the field and urging the dismissal of Irene. Shortly afterwards a more violent diatribe was placed under their bed while they slept, but one of Irene’s eunuchs was on guard and arrested the man, who betrayed the plotters. Then the death of Bohemund put an end to the war in the West, and the indefatigable Emperor turned to face the Turks and the Crusaders who had settled in the East. Irene became seriously ill when she accompanied Alexis to the Chersonesus in 1112, yet we find her with him at Philippopolis in the following year.

Irene was little more than nurse to the gouty monarch during these campaigns, yet we must, in order to understand her last fierce word to him, glance for a moment at the conduct she observed in him. She had for years seen how he conducted wars and diplomacy chiefly by guile and deceit, and she now saw how he converted heretics. A few years before he had set out to refute the tenets of the “Bogomilians,” one of the many sects, mingling Eastern and Western ideas, in which age after age the protestant feeling against the superstitions and corruption of the Greek Church found expression. By the use of torture Alexis discovered that the leader of the sect was a staid and venerable monk named Basil, invited the monk to visit him in the palace, and, by a grossly hypocritical pretence that he himself leaned to the sect, induced him to talk freely of their doctrines. When he had “vomited his heresy,” Alexis drew aside a curtain, and showed the man that a shorthand-writer had secretly taken down his words. Basil was imprisoned, and Alexis spent hours in argumentation with him; and a few years later the “archsatrap of Satan” and large numbers of his followers were burned alive for refusing to see the force of the imperial logic. Similar tactics were now adopted at Philippopolis, where Alexis and Irene spent the greater part of 1113. It was an important seat of the Paulicians (a modified Manichæan sect), and Alexis spent days in disputation with their leaders; when persuasion failed, he resorted to bribery and coercion.

These few instances will suffice to illustrate the relations of Irene and Alexis, and we may hasten to the final scene. The last years were occupied with a campaign against the Turks, but Alexis was now seriously ill and the enemy advanced and reviled him for his cowardice. In their camp they bore about a bed with an effigy of Alexis pretending that gouty feet prevented him from taking the field. Irene was awakened one night with the news that the Turks were upon them, and Alexis was forced to let her return to the capital. There is no doubt that she accompanied Alexis on these later campaigns only because he compelled her, and one wonders whether he was not afraid to leave her in the palace. He retreated, and recalled her at once to Nicomedia. Here she found that his own subjects were singing, on the streets, comic songs about the gout of the great Emperor and his flight before the Turks. He was undoubtedly very ill, and in the spring of 1118 he was brought back to the palace to die. Then arose a fierce struggle for the throne.

Anna Comnena, the princess born in 1083, had been betrothed, in her tender years, to the Empress Maria’s pretty boy Constantine. The boy died, however, and in time she was married to the distinguished and ambitious noble, Nicephorus Bryennius, who received the title of Cæsar and then that of Panhypersebastos (“the august above all others”). Bryennius was a scholar: Anna a prodigy of female learning, a cyclopædia of arts and philosophy, a most imposing writer, and—strange to say—a spirited and ambitious princess. The brilliance of this imperial pair dazzled the Court and the capital, and it was very naturally suggested that the crowns could not be placed on wiser and more fitting heads than theirs. Such was the opinion of Irene. But Alexis and Irene had three sons (John, Andronicus and Isaac) and three daughters (Maria, Eudocia and Theodora) besides the gifted Anna, and the crown belonged, by such right as was recognized in Byzantium, to the eldest son. John was a plain, quiet youth of—as events proved—sterling character and no ostentation. His father appreciated him, though few others knew him. He observed with sullen eyes the efforts of his mother to displace him, and secretly engaged officers and nobles to support him against her; and Irene retorted by forbidding them to have any intercourse with John. This struggle was now to reach the height of passion round the deathbed of the Emperor.

The last ten pages of Anna’s narrative give a vivid account of the progress of her father’s illness. She was appointed to a kind of presidency over the skilled medical men who were summoned from all parts of the Empire to check the “mysterious” illness—of a gouty old man of seventy. I will quote only that, when relics failed to improve his condition, they applied a red-hot iron to his stomach—to counterpoise the pain at the extremities, perhaps—and, when this brought about no relief, removed him to the Mangana palace, near what is now known as the Seraglio Point. Irene watched her husband night and day (carefully excluding John), and, although the monks assured her that he would live to214 visit the Holy Sepulchre, she shed “more tears than the waters of the Nile,” Anna says.

In the afternoon of 15th August 1118, Alexis lay dying on his purple couch. The description of the scene, which closes Anna’s narrative, has reached us only in a torn and fragmentary condition, but the chronicle of the monk Zonaras, who lived about this date, is full and authoritative, and it is supported by the chronicle of Nicetas. Their account of that last scene in the life of Alexis shows that Anna Comnena crowns her work with a masterpiece of deliberate lying. She depicts her mother overwhelmed with sorrow at the impending loss of her husband, crying that thrones and crowns are vanity, and calling for the black robe of a nun, if not actually shearing her golden tresses, before the last breath has left her husband’s body. Of the real features of the scene there is merely a faint and vague report that John is hurrying to the main palace and the city is disturbed. The truth is less touching, more dramatic.

Availing himself of a temporary absence of his mother—probably bribing the guards—John entered the room and approached the bed of the dying and speechless monarch. Alexis was still conscious; but whether he gave his ring to John, or the son detached it from his finger, the chroniclers are not agreed. No doubt Alexis was too feeble to detach and give it, and merely looked assent when John detached it; Alexis had always favoured John. By the time Irene returned John was galloping across the imperial domain to the chief palace (either Daphne or, more probably, Bucoleon), and the Empress was furious. She angrily observed to Alexis that his son was seizing the throne while he yet lived. Alexis feebly, and equivocally—though some writers say that he smiled—lifted his hands and eyes toward heaven, as if to intimate that there was the only throne about which he was now concerned. Nicephorus Bryennius was summoned, and Irene urged him to unite with her in claiming the throne. He refused, and she215 returned to her husband. The last words, loudly and harshly spoken, which she gave the dying man were: “Husband, while you lived, you were full of guile, saying one thing and thinking another; you are no better now that you are dying.”29 We may assume that Alexis had deceived her about the succession. He died that evening, so completely deserted that there were no ministers to perform the ceremonial services over his remains. The interest had passed to the main palace.

John had found before the door a regiment of the Varangians, who, even when he showed his father’s ring, refused to allow him to enter. But they grounded their formidable two-edged axes, and stood aside, when he swore (a false oath) that his father was already dead, and had appointed him successor. He at once secured the palace and the crown, and the reign of Irene Comnena was over, the hope of Anna Comnena shattered. John would not even issue to attend the funeral of Alexis, so determined he was to hold the palace. The women were beaten by the quiet, ugly little youth they had despised, and a few words of the chroniclers dismiss them from the stage of history.

Irene, changing her name to that of Xene, retired to a monastery which she had built in the city. Curiously enough, a manuscript copy of the rules of this monastery has survived, and been published, so that we have an interesting glimpse of Irene’s later years and of the monastic life of the time. The inmates were to number between thirty and forty, were to sleep in a common dormitory, and were to elect a prefect. Besides the steward, who was to be a eunuch, and the two chaplains, who must be monks and eunuchs, no man was ever to enter the monastery, and the reception of visitors was strictly controlled. There was midnight office to be chanted, and the remaining offices and meals and other216 details were planned much as in a modern “convent” (a Latin word unknown in the East). Each nun was permitted to have a bath once a month. Irene little dreamed, when she sanctioned this ascetic scheme, that she would one day be forced to adopt it. But the last glimpse we catch of her in the chronicles suggests that she did not embrace it in all its rigour. Fifteen years later, when another Irene came from the West to wed the Emperor Manuel, she noticed, among the crowd of notabilities who welcomed her to the city, an aged lady whose dark monastic robe was relieved by strips of purple and edges of gold. When she asked the name of this royal nun, she learned that it was the widow of the great Alexis. Probably Irene tempered the diet and prayers, as well as the robe, of the monastery. She was then seventy-seven years old, and cannot have lived much longer.

Anna Comnena seems to have retained her liberty and rank at the accession of her brother. He soon proved his worthiness of the crown, and the corrupt nobles and ministers, shrinking from his inflexible justice, gathered darkly about Anna and Bryennius. Anna was the most active spirit in the plot, and it would have succeeded but for the irresolution, or humanity, of Bryennius. The doorkeeper of the palace was bribed, and John might have been murdered in his bed. When Bryennius failed to use the advantage, Anna turned upon him with fury. Nicetas tells us that she complained, “in somewhat obscene language,” that Nature had made her a woman and him a man. John was content to confiscate their property; though, when he gave Anna’s luxurious palace and all it contained to his Turkish minister, that strange type of Byzantine official begged his master to lay aside his anger and permit him to restore the palace to Anna. Some years later she entered her mother’s monastery—probably when her husband died in 1128—and lived there at least twenty years, writing her famous work, the “Alexiad,” a chronicle of her father’s deeds. That work—affected, insincere and ambitious—reflects the character of its author, nor can its lavish use of the art of suppressing some facts and enlarging others efface from our memory the ignoble attitude of Irene and Anna by the bedside of the dying Alexis and toward his legitimate heir.

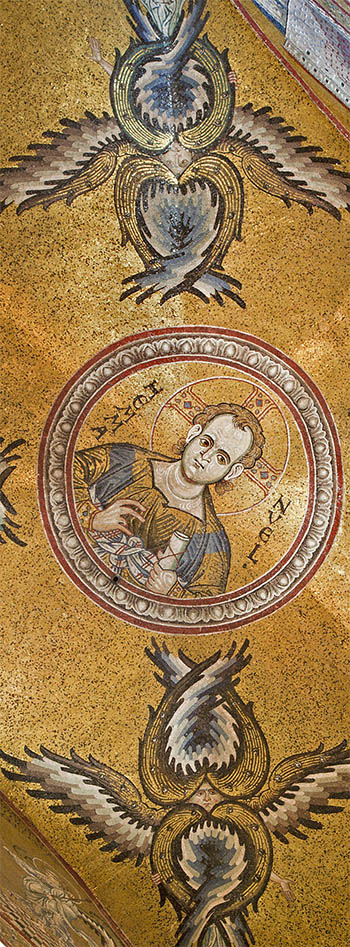

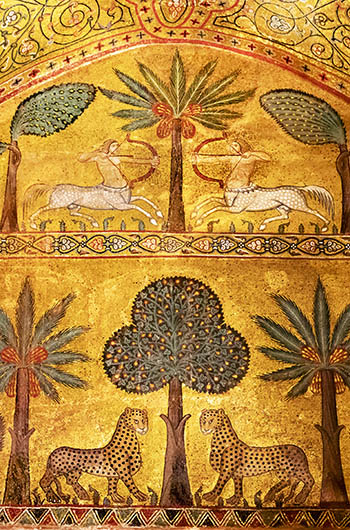

click here for icons of christ

click here for icons of christ click here for icons of the theotokos

click here for icons of the theotokos click here for icons of angels

click here for icons of angels click here for icons of saints

click here for icons of saints