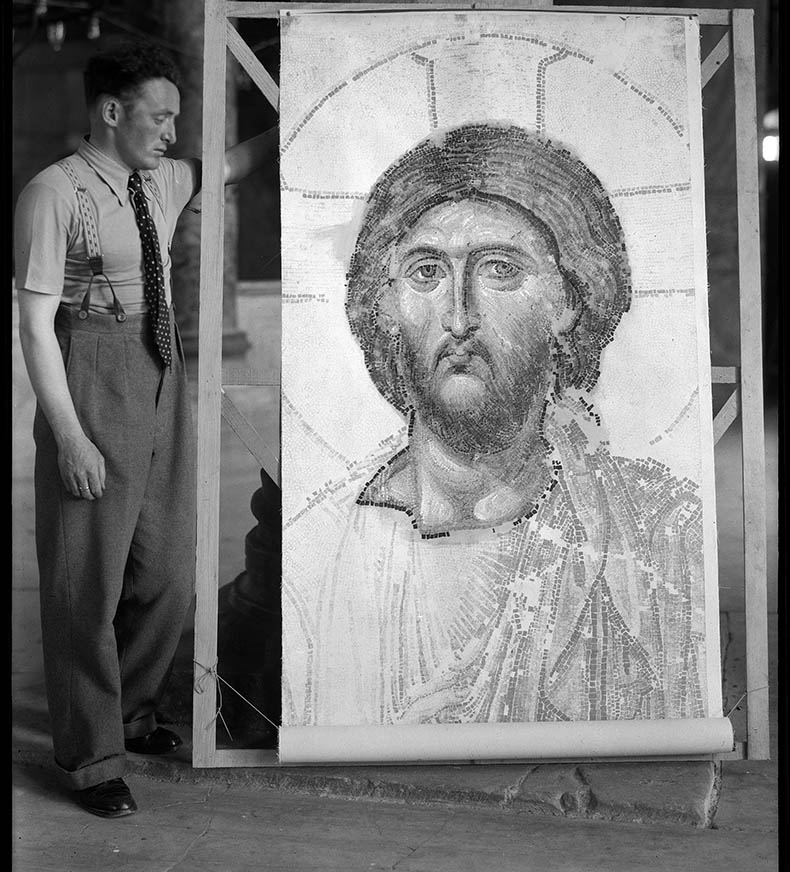

The image above is another of the first color pictures taken after the restoration was complete in the late 1930's.

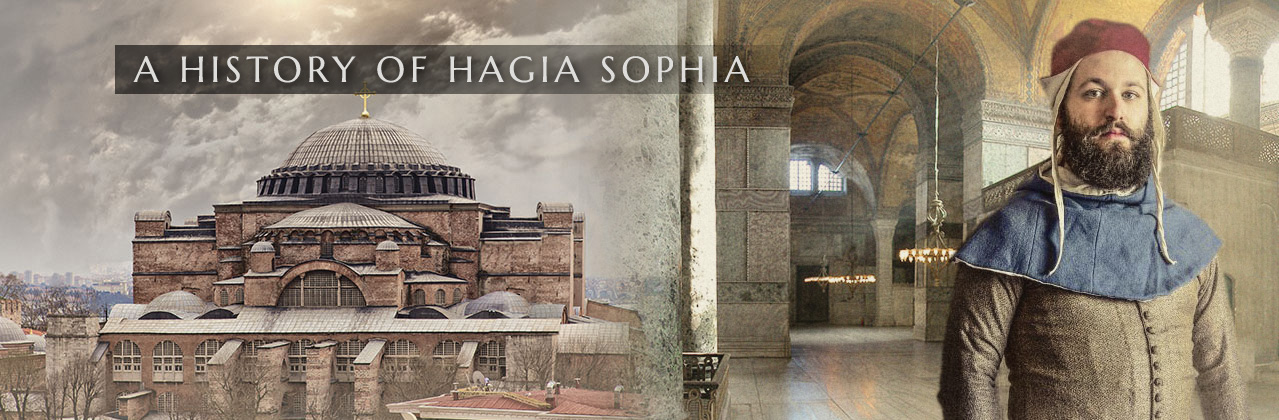

On Tuesday, May 29, 1453 the ancient dream of Islam to capture Constantinople, which originated with Muhammad, the founder of the religion was achieved by his namesake, Mehmed II. After allowing his troops to sack the city and terrorize the people, killing them or capturing them to ransom or sell as slaves, the Ottoman Sultan ordered the destruction of the city to seize. He entered the city on horseback and rode through the doors of Hagia Sophia. He could not travel on foot because the church was full of dead people and the floor was covered in blood and gore. Islamic troops were in the process of smashing the icons and stripping them of any valuables they could find. The silver chalices, candlesticks, gospel covers and other things used in the liturgy were taken and broken up. Priests and nuns were tortured in search for hidden treasure. Running out of precious things (It had been a very long time since Hagia Sophia had any treasures of value). The frenzied looting even extended to hacking at the marble ambo, sanctuary screen and the altar-ciborium. The ignorant soldiers believed they were made of precious stones. Mehmed II ordered a stop to the destruction of Hagia Sophia and declared that it was his personal property. Next he dismounted from his horse, climbed onto the great altar and recited a Muslim prayer converting Hagia Sophia into a Muslim mosque. Eleven hundred years of Hagia Sophia as a Christian church ended.

Because Hagia Sophia was the personal property of the sultan it had a special position among the mosques of Constantinople. It was not open all of the time, only by special permission of the Sultan. Areas like the galleries went for decades being closed to the public. No changes could be made without the Sultan's approval. This meant that the Ottoman sultans felt a special responsibility for the building, its decoration and history. It was not easy to get inside, especially for foreigners. Islamic zealots could not destroy the mosaics, they belonged to the Sultan. For hundreds of years - up until the middle of the 18th century - most of the mosaics were left exposed. The only ones covered up were the wall panels which were subject to hacking. The covering up was done to protect them, they could have been scraped off instead of being painted or plastered over. It was much more difficult for vandals to get at the vault mosaics, so nothing was done to them and they were never covered up.

The Sultans collected a large number of Byzantine things, including relics and manuscripts, which were considered valuable and interesting trophies from the past.

A greater threat to the mosaics were earthquakes and modern oil-based house paints.

As time went on Islamic extremists increasingly focused their attention of the Christian mosaics of Hagia Sophia and wanted them destroyed. Around 1710's the Sultan Ahmet III allowed an European engineer named Cornelius Loos attached to the King of Sweden, Charles XII, who was the the guest of the Sultan, into "Aya Sofa" to make detailed drawings of it. A few years earlier a few other explorers had made drawings of the mosque. From the Swedish drawings we know that the almost all of the mosaics of Hagia Sophia that were in place in 1453 were still there and could be seen up close. Sometime later in the 18th century all of the mosaics were covered up. We don't know when for sure.

In the 1840's the Sultan ordered a complete restoration of Aya Sofa. The work was done by the Fossati brothers.

When Hagia Sophia functioned as a church, the South Gallery was reserved for the emperor and his family, courtiers, servants and guards. They all would have been splendidly dressed in silks, velvets and other fine materials. The soldiers - in later times bearded Viking and Englishmen - were dressed to the hilt in their Imperial military uniforms, carrying splendid swords and shields, and wearing gilded and silvered polished armor set with gold enamel that glinted as they moved. Unlike Western European churches the Byzantines did not remove their hats in church.

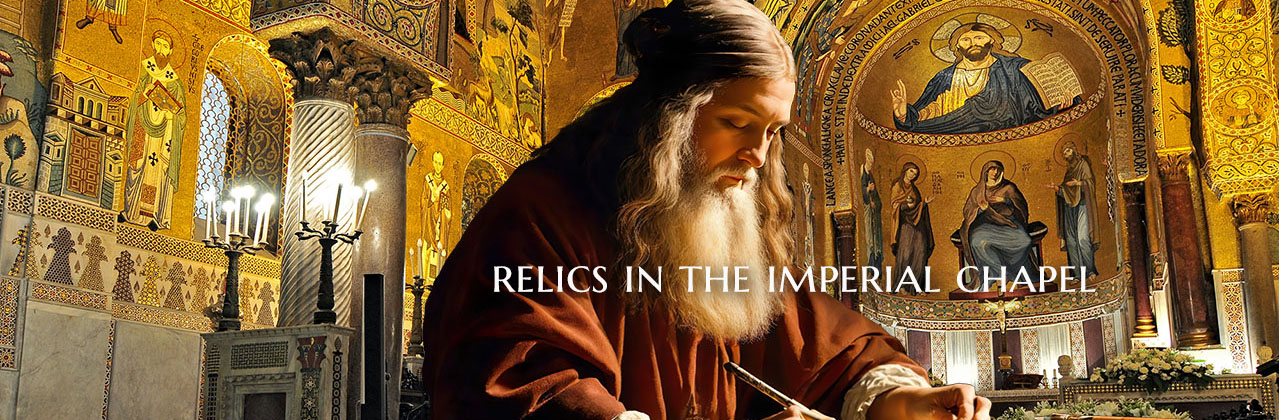

Above is a reconstruction I did showing how the South Gallery might have looked in the 12th century. Mosaics of seraphim and cherubim with Christ like this were in this exact spot and had survived up until 1850. These mosaics are from Sicily and were put up for Norman Kings by Byzantine artists. Seraphim and cherubim guarded God in His heavenly court. There are a couple of things that are wrong. The face of Christ is facing the wrong way, for one. The scale of the people is pretty close.

The galleries of Hagia Sophia could accommodate thousands of people and were especially crowded on feast days and for special services or ceremonies. At night and in the early morning the gallery was virtually deserted except for a few clergy or bored guards. Hagia Sophia had a maintenance staff that cleaned the church and kept the lamps filled with oil and lit. The had tall ladders and had gang-ways along the tops of cornices to access all of the chandeliers and hanging lamps. The altar was washed with rose water by clergy everyday. There was also a fire brigade assigned to the church on 24 hour watch. The central and eastern sections of the south gallery were walled off with a ornately carved marble partition that still has its original 6th century wooden beams along its top. From its great height and exceptional position, the south gallery was the supreme vantage point in the church, with a complete view over the nave and the the altar area. During the liturgy communion would have been brought to gallery and served to the worshipers there.

One could enter the gallery directly from the Great Palace without having to pass through the nave of Hagia Sophia. Outside there was a private elevated covered passageway - the Anabasion of the Chalkê - from the palace that ended at an external wooden spiral staircase. The passageway was really cool, it had windows you could open and look out of and see people in the streets and squares below. They could see you, too. It was even possible to address crowds of people below. The spiral stairs are long gone, but the portal remains. There are inscriptions scratched into the marble door surround on both the inside and the outside that are over a thousand years old, and in different languages. Hagia Sophia is full of ancient graffiti - hundreds have been recorded - including FOUR Viking boats!

The South Gallery was brightly lit by natural light during the day. Sunlight would spill over the balustrade into the nave below. The walls and ceilings were covered with gold glass mosaic which reflected and bounced light around gallery like an inner sun. In Justinian's time the vaults were covered with ornamental mosaics set in plain gold backgrounds. Later some of these were replaced with mosaics of saints, Christ and angels. In one vault was a scene of Pentecost, with fiery tongues of light descending onto the heads of the Apostles from the Holy Spirit. There were also gigantic Cherubim and Seraphim surrounding a Christ Pantokrator, which was set in a great circular medallion in the center of the vault. The huge windows have marble frames that were set originally with panes of clear greenish glass, then plaster squares set with round glasses during Ottoman times, and now back to glass panels.

The gallery was even more beautiful at night when it was lit by candles and oil lamps. There were great silver candelabra hanging from the ceiling and single oversized glass lamps in groups of three suspended from cross-rods in the arcade arches. The candelabra were also set with glass cups that held burning lamp oil. There were also big silver candle stands in front of the icons and mosaic panels on the walls. There is a special property in semi-transparent gold glass mosaic that is especially effective in reflecting lamp and candle light. The glass cubes were set at angles and in patterns to magnify this effect. Evening and night vigil and vespers services in Hagia Sophia were unforgettable events. At twilight and then at night the air would smoulder with flickering light. The oil in the lamps was fragranced which added to the sensual experience. The chanting, voices of priests and deacons and the voices of the choirs reverberating from the walls and vaults added sound to the sensational overload. Now we can only imagine this lost and mysterious splendor which contrasts so dramatically with in the cold bright light and hordes of tourists we see today.

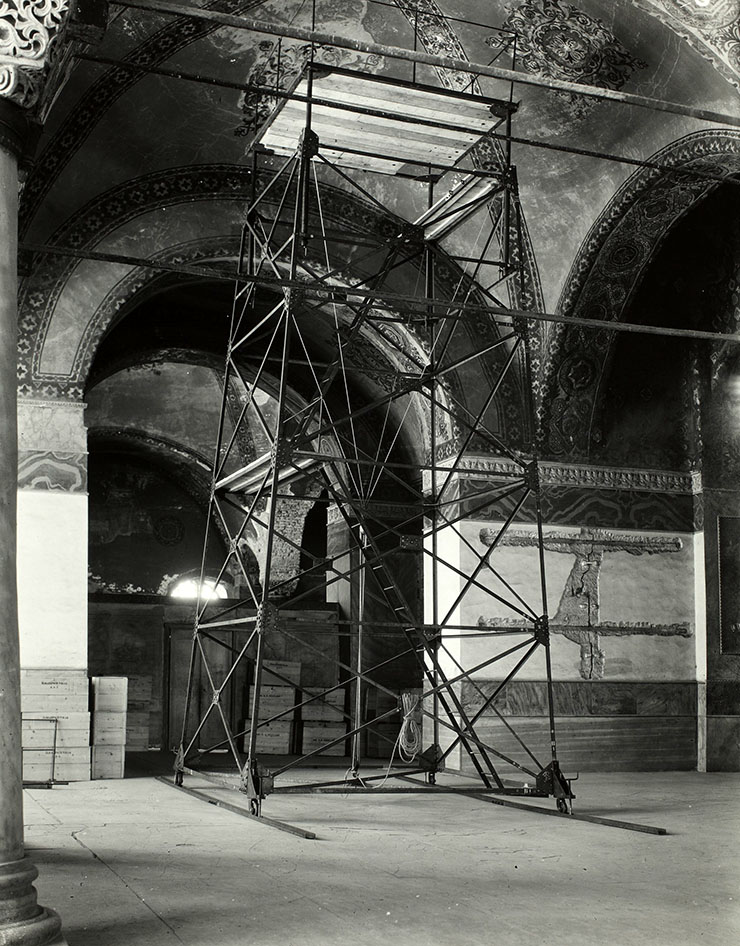

From May until June in 1936 the scaffold was moved around the South Gallery to search the vaults for mosaics that were last seen in the 1840's. These mosaics were lost because the Fossatis used ordinary oil house paint on top of plaster when they recovered them. The oil paint created a seal retaining water underneath it. This caused the mosaics to blister and fall off. They team was extremely disappointed to discover these awesome mosaics were lost forever.

This area of the south gallery (seen above) was also a location for assembly of the Patriarchate, the offices of which climbed up the side of Hagia Sophia, filling the space between the church and the great square of the Augusteum. Connected with the second floor here on the south side of the Church, remains of the Patriarchal offices still exist. On the right hand side of the entrance to the church is a beautiful room now called the “Baptistery” that was actually the main Patriarchal reception room. Other rooms survive in the walls and passages on this side of Hagia Sophia, but they are not open to the public so few see or know much about them. This area of Hagia Sophia is particularly bright and spacious because of the huge windows and the fact that the facade here is unobstructed. A significant part of the original marble revetment has been saved here.

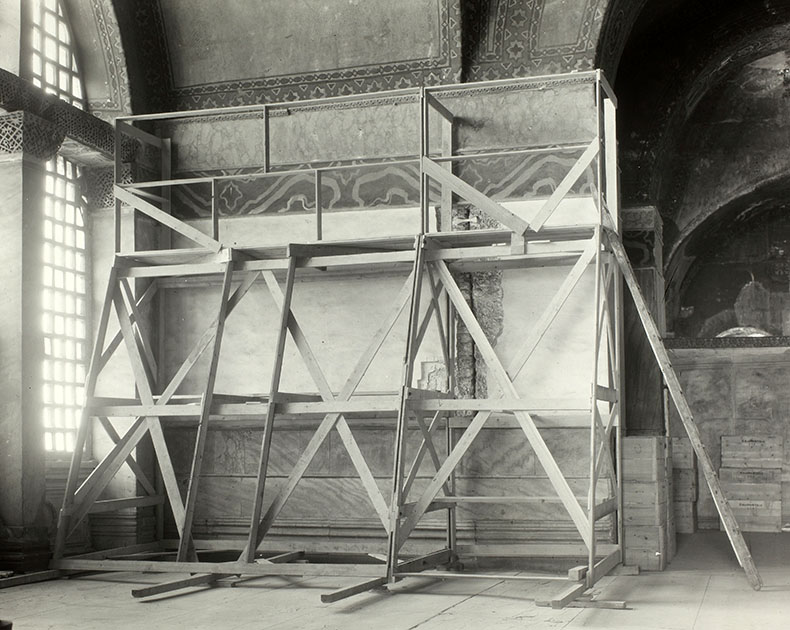

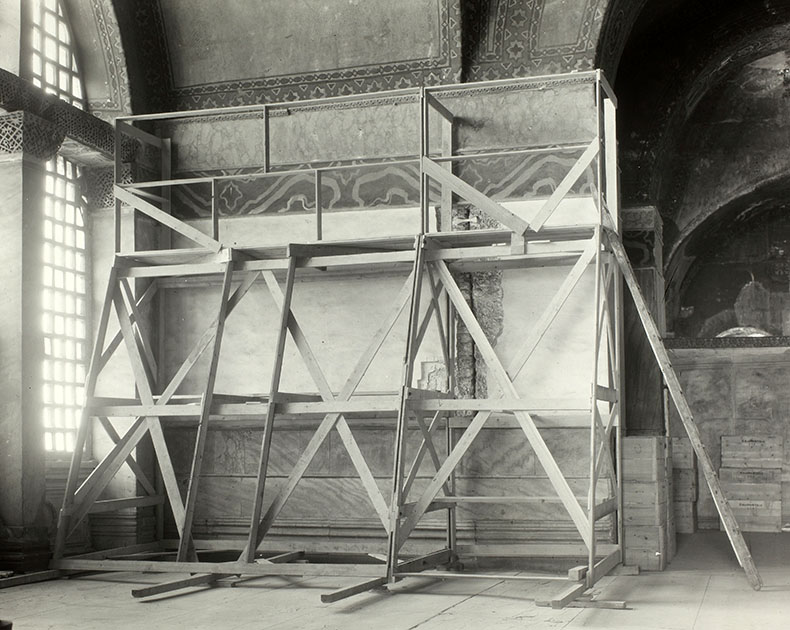

The picture above shows a wood scaffold erected so the restorers could examine the area where they hoped they would find the Deesis mosaic. Prior to the restorers arriving to hunt for mosaics workers had opened up a part of the panel to examine the cracks there. In doing so they destroyed half of the figure of John the Baptist!

Thomas Whittemore was a tiny man, 5 feet tall and weighing just 110lbs. He was deeply religious and a vegetarian. Although he was short he seems much larger in photographs dressed in formal attire and wearing a hat. His men called him Mr. Whittemore, Tom or "Chief". Before the Russian Revolution, during World War I he had worked with the Grand Duchess Tatiana's American Automotive Ambulance corps. After the Revolution he helped tens of thousands of Russians to escape the Bolsheviks. He organized relief organizations to house and feed the refugees on the Prince's Islands, just outside the city. He raised millions of dollars to finance this work. He was distressed and mortified at the human cost of the revolution and witnessed the beginning of the wide-spread destruction of religious art and churches by the new Soviet regime. Whittemore's interest in Russia had been, in large part, focused on the Orthodox - Byzantine - religion and its art. He had a fascination with the beautiful and spiritual things created in the Byzantine world, that were virtually unknown in the west at that time. Until then, western art experts had always looked down on Byzantine art as unworthy of serious study. The irregularities and strange perspectives were not easy to appreciate by historians, most of whom were Protestants, who believed that religious art must be orderly and free of anything that smacked of idolatry, especially icons. This attitude was changing in the 1920's when the beauty of Byzantine art was being widely promoted by artists like Matisse. "Sailing to Byzantium" was published by Yeats in 1926 followed by the poem "Byzantium" in 1930. This change in attitude came at just at the right time to create thee Byzantine Institute of America which was led by Whittemore. He had many rich friends who were ready to make sizable donations and support the work of the institute, year after year. He was joined by prominent individuals, such as Charles R. Morey, John Nicholas Brown, Charles R. Crane, George D. Pratt, and Matthew S. Prichard.

Whittemore was something of an eccentric. He had a flamboyant personality which was not appreciate by his more colleagues who criticized his lack of scientific discipline. They also complained that in his later publications documenting the work that had been done on Hagia Sophia he took credit for the work of others, which is true. He was invited by President Roosevelt to discuss his work in Hagia Sophia which was widely reported in the press. He was able to show Roosevelt a color movie that had been made of the restorers at work. There is tremendous value in publicity in the promotion of cultural preservation. This fostered jealousy by those who don't share in the limelight with him. Some felt they deserved more glory than Whittemore. There has always been tension among Byzantinists between those, like Whittemore, who focus on art versus those value scientific fact over human experience.

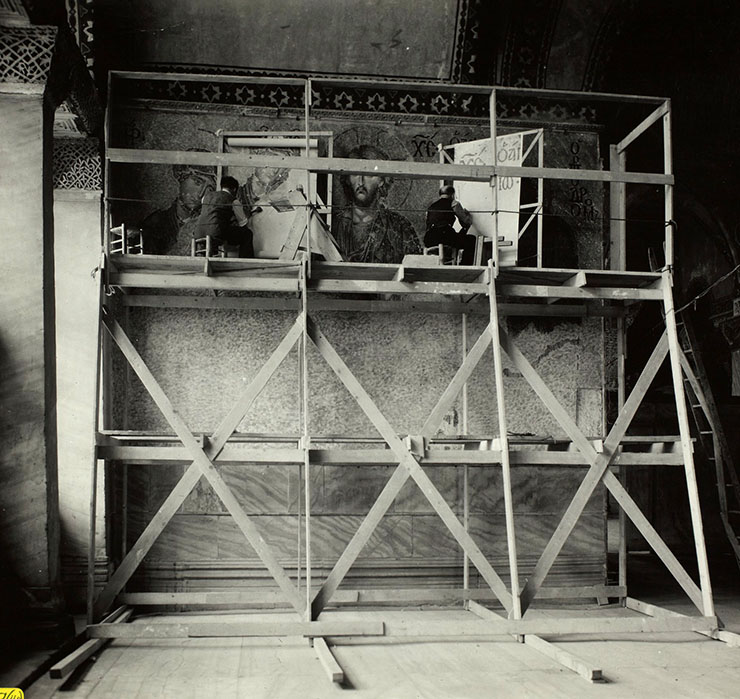

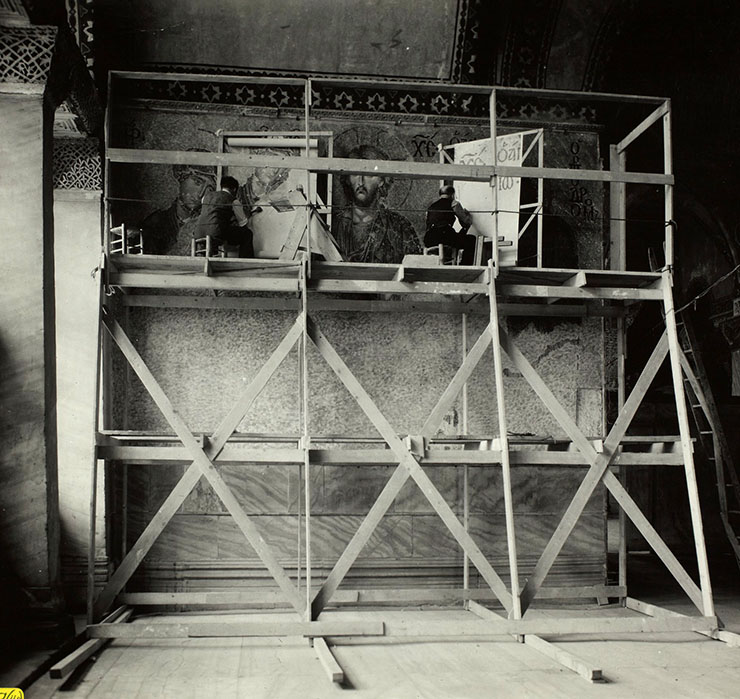

Two artists doing tracings of the Deesis, on the left is Aldi Bey, a Turkish architectural student who worked for Whittemore in Hagia Sophia and on the right is Nicholas Kluge, a Russian refugee and former member of the Imperial Russian Archaeological Institute. You can see they are working in natural light. Nicholas worked right up to the last days of his life and virtually died on the job. He was climbing all over the scaffolding when he was 77. Ernest Hawkins noticed Nicholas was exhausted but Kluge would not listen to him and stop working.

Each season of the Byzantine Institute in Istanbul cost between $17,000 and $31,000. This was nothing compared to the money Whittemore had raised for the relief of Russian refugees, which had ended by the time he was raising money for Hagia Sophia. After that work had been completed Thomas Whittemore and the Byzantine Institute moved to the Chora Church and the consolidation and restoration of the mosaics there, which had never been concealed and required their emergency attention. Whittemore died in June, 1950 and no one was able to replace him and his "mystic" view of things. Most of fund-raising relationships were personal and were difficult to extend beyond his death. No one could replace his personal enthusiasm and intense passion which was always the source of the strength of his advocacy. Artists, like Matisse, were his close friends. His donors were "converts" to the glories of Byzantine art and culture that he had nurtured over years of patient evangelism. Many of them where "Bachelors of Art" like himself, Whittemore never married. It is amazing how much of his advocacy of Byzantium was conducted over lunches or dinners in fine restaurants with groups of intellectually minded men, like himself, who were served fine wines and caviar. He had created his own brotherhood that could not outlive him. After he was gone the Byzantine Institute entered a difficult phase in its relationship with Turkey and it was banned from work there for a number of years.

In 1931 Hagia Sophia the decision was made to close the mosque for a period of study and restoration before it reopened as a museum. The Turkish authorities were so pleased by the immediate progress that had been made that they opened the museum to the public as soon as it was possible to do so, even as the work was underway and scaffolding was erected in various parts of the museum with restorers climbing up and down ladders. Whittemore and his new Byzantine Institute of America had the complete support of the Turkish government and the first President of Turkey, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk. The President took an active interest in the progress of uncovering the mosaics and met with Whittemore to review their progress and see pictures of the work. The Turkish Government issued a special degree about the conversion of Hagia Sophia from mosque to museum. It dictated that the new museum should retain any Ottoman additions that were necessary to tell the history of Hagia Sophia, but these should not obscure anything Byzantine, which was recognized to be the most important period to the building as a museum.

1931 was a treasure hunt; using records left by the Fossatis 80 years before, they using copies of their notes and their book to find locate mosaics The Fossati brothers, Gaspare and Giuseppi, in their 1849 restoration and redecoration of the mosque, discovered, sketched, and re-covered all of the figural mosaics they discovered. The Sultan had instructed them to preserve the mosaics for the future, wisely recognizing that no one knew how Hagia Sophia would be used in the future. The Institute had the brothers’ sketched reconstructions, and ideas about where the works might be located, but only had the vaguest hope to find them. This was complicated by the damage Hagia Sophia had sustained in an 1894 earthquake. This earthquake had destroyed the nearby Grand Bazaar. Earthquakes effected different parts of Istanbul based on the ground beneath the buildings. Hagia Sophia was built on bedrock so it should have not have had a serious effect on the building itself, but the mosaics were extensively damaged for some reason, and there was no guarantee that anything that was seen in 1850 remained. There had been an extensive restoration of the 1894 earthquake that went on for almost 20 years. We how know that huge areas - 50% - of the surviving mosaics were scraped off and the walls, vaults and domes were replastered. Once can blame the restoration techniques of the Fosattis for the loss of so much mosaic. They covered them back up with new plaster which they painted over in oil paints. The oil paints created a barrier to the evaporation of moisture through them and made the mosaics detach themselves from the wall. A few years after the Fosattis painted Hagia Sophia the paint was badly pealing off in strips.

The Fosattis did not take much interest in the mosaics of the vaults of the south gallery, but fortunately Wilhelm Saltzenberg did. In contrast Saltzenberg did not document the Deesis or the Imperial portraits, which must have already been recovered by the time he arrived. Things were going so fast that Salzenburg only had a few days to record mosaics as they came to light and then vanished once more. After he got back to Germany he published a big sumptuous illustrated guide to Hagia Sophia that included watercolor renderings of mosaics and decorative patterns he saw throughout the church. To some extent his watercolors included restorations of missing parts and they were drawn with the precision of a draftsman that eliminated many irregularities. This book - along with the records of the Fossatis were the two resources Whittemore had to locate the mosaics of the south gallery.

For generations Turkish tour guides had offered handfuls of mosaics from the south gallery to their customers. The gold mosaic was especially valued by the guides because it brought bigger tips from tourists. Some of them hesitated to take these souvenirs, knowing they were contributing to the destruction of the mosaics. The upper galleries of Hagia Sophia were closed to visitors from 1894 until 1907 because of raining mosaics and chunks of plaster as a result of the 1894 earthquake. Knowing the mosaic cubes had value they must have been collected by cleaners sweeping up the mosque and were sold or given to the guides. In the figure of the Virgin of the Deesis we can see how someone has climbed up on the window sill and picked out gold mosaic from the golden band of maphorion by hand. This whole area of the top left of the mosaic has either been damaged by man or by rain coming in through broken or missing panes of glass. The work of restoration in Hagia Sophia from 1894 - 1912 seems to have been undocumented and unsupervised by conservation experts - no attempt was made to save or record anything.

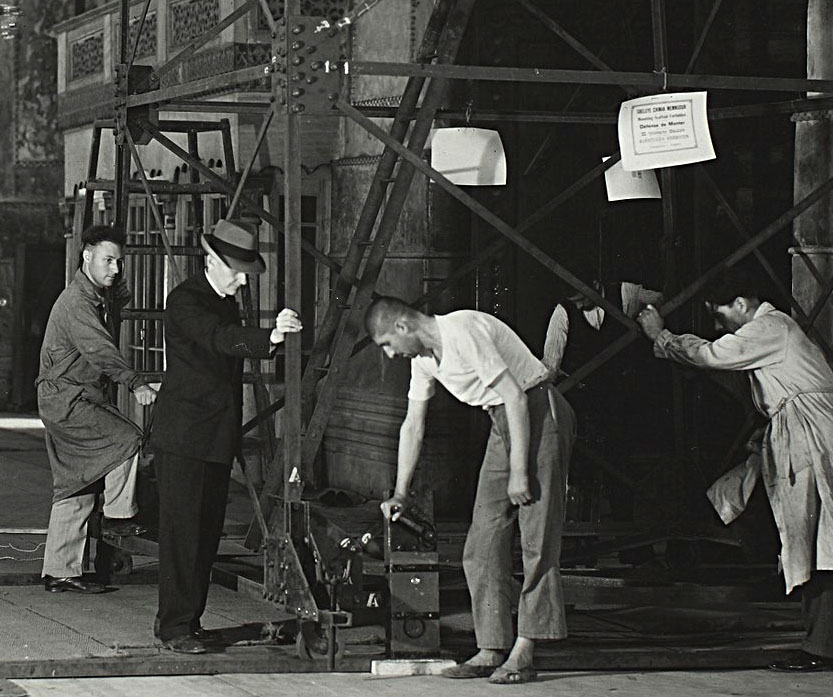

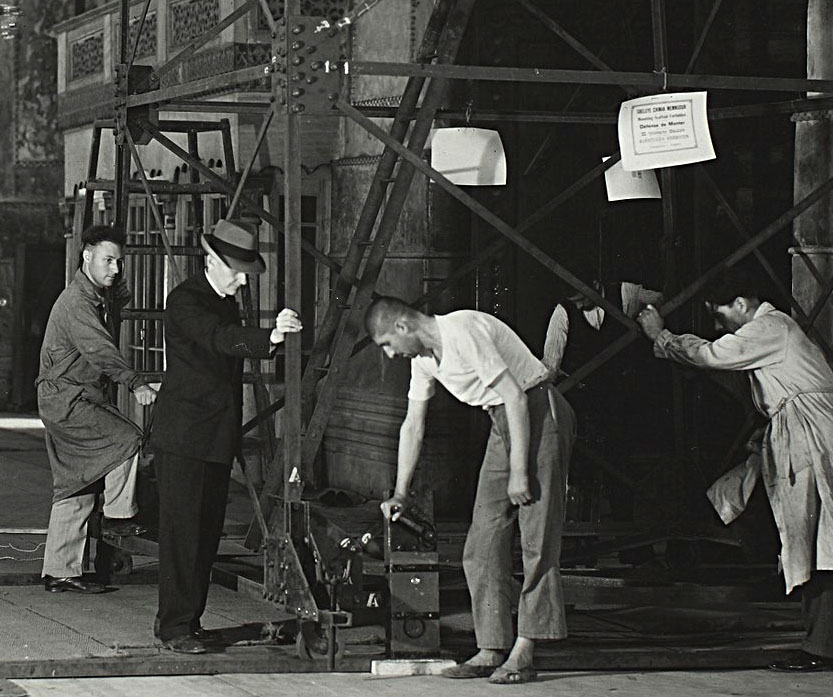

Everybody - including Whittemore - moving the scaffolding in the inner narthex. Here they were working on the restoration and cleaning of the crosses in the vaults from the original decoration of the church during the reign of Justinian. This is obviously a staged publicity shot. The crosses and the Church Fathers in the Typana were the last of the mosaics to be worked on. The guy on the far left is Ernest Hawkins.

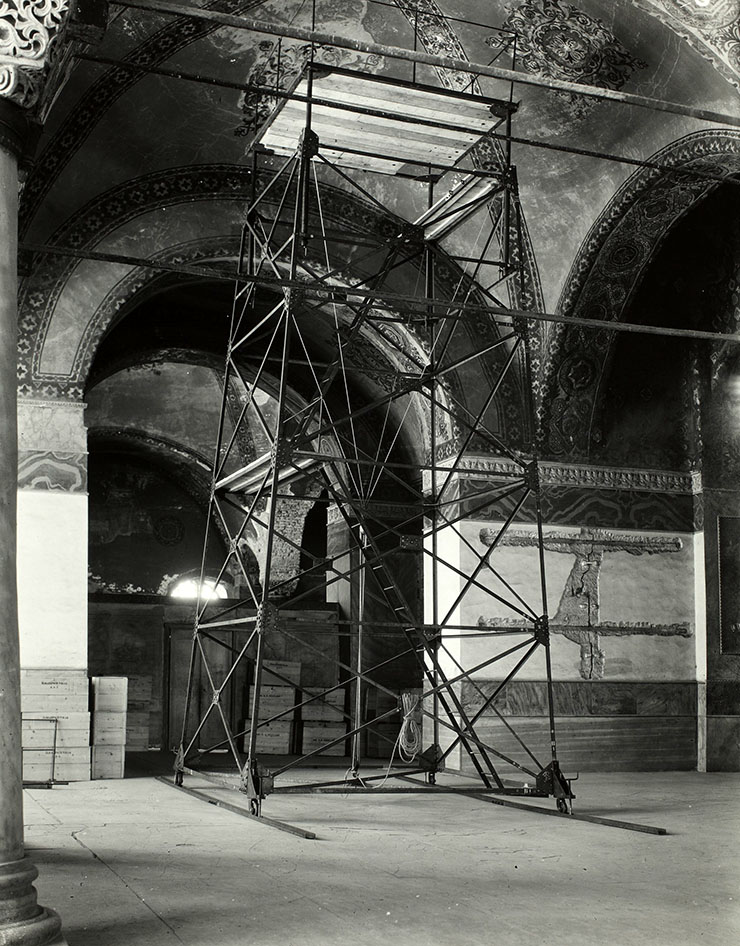

The iron scaffolding was supplied and erected by Jones Engineering. It was moved around the church as needed. The apse scaffold was made of wood. Sometimes there were too many people working on a mosaic panel and there was no room to work on the scaffold - this was a problem on the church fathers in the tympana. Hawkins had to demand Kluge go work elsewhere. He was very old at the time, what he was doing on scaffolding at his age is a mystery.

One cannot forget to list the men who did the work for Whittemore, Richard "Dick" Gregory and his brother William "Bill" Gregory, Albert Lye, J. Jack Brennan, George Flockton, Alywin Green, Ernst Hawkins and Robert Van Nice, who worked as a spy for the OSS - the intelligence agency of the United States - during WWII. All of these guys were involved in the discovery and conservation of the mosaics. Whittemore found most of them in Britain - some of them unemployed artists - and paid them almost nothing to follow him to Istanbul and work in Hagia Sophia. It was the depression of the 1930's and work was hard to find. His workers were happy to have an exciting job in an exotic local. Every worker had to be approved by the local police in Istanbul after arrival and carry documents. Whittemore also had an administrative team working out of the new Byzantine Institute offices in Paris. Here he employed Russians, like Nicholas Kluge, to organize and compile all of the research that was coming out of Hagia Sophia. The workers in Hagia Sophia kept extensive daily notes that you can read online, so you can follow the work day-by-day as it happens. This was tedious for them, they were instructed to stop taking notes in pencil and record them in ink. There were continuous photographs being made and they also made films which you can watch on line.

There are very interesting notebooks made by George Flockton who studied and cleaned the revetment of the apse. There are beautiful friezes of inlaid marbles that he has both described and drawn. The apse had lots of panels of red porphyry and colorful white onyx which is also called oriental alabaster. Flockton notes that the white onyx, a fragile material, used in apse has frequently split and fallen from the wall. The Fossatis replaced this with painted white plaster which had darkened and turned gray. Most of the panels of red porphyry were made of of pieces of stone that had been skillfully been scalloped on their edges and spliced together. I have a page of 45 images of the marble revetment here.

Electrical lights were added to help the work, but their glare and distortion actually made the work harder. It took some time to figure out how to use them effectively. The men preferred to work in natural light.

They lived together in housing supplied by the Byzantine Institute. They learned as much Turkish as they could, the notebooks have translations of useful phrases and Turkish grammar. None of them knew long long the work would go on and whether they would return for the next season. Some of them started in 1933 and continued until 1946. They were paid around $180.00 a month.

The work was done on scaffolds starting at the top and moving down. There first responsibility was uncover and preserve loose tesserae and secure loose plaster and mosaic with copper clamps. Next they cleaned mosaic and filled in missing areas with new plaster. They were experimenting with new techniques of restoration and conservation on the job and were very concerned with preserving the original mosaics without adding to them. There were many loose tesserae discovered and each one had to be dealt with individually. As they moved down they were exposing mosaic that had not been see for almost 100 years. They had few records to go with and didn't know exactly were some mosaics, like the portrait of Emperor Alexander was. It took a lot of searching until he was found in the North Gallery.

While they were working in the Galleries they were also working elsewhere in Hagia Sophia on other mosaics. Whittemore wanted them to discover everything so he could raise more money and keep the work going. At any time the Turkish government could have halted work. Donors had to be approached for every season of work. Pictures were taken constantly to document what was being done for both scientific and fund raising.

They returned to Hagia Sophia every year, working from roughly April until November. From 1935 - 1938 they worked in the galleries. They weren't exactly sure what they would find. Wilhelm Salzenburg had published watercolor and drawings - along with written descriptions - of extensive surviving mosaics in 1850. No one was sure what was still there and exactly where mosaics would be found. This was especially true of the Deesis. The Imperial portraits were located and uncovered first. They began with the panel of Constantine Monomachos and Zoe and then moved to the panel of John II Komnenos and his wife Eirene. Next Whittemore examined a wall in the central part of the upper south gallery, west of where they found the Imperial Portraits, quickly striking "gold". The team had found what they were looking for.

In 1933, the space above this marble revetment and the vaults were plastered over and painted. When Thomas Whittemore and his team arrived to begin work they found a thousand cases of documents from the Hagia Sophia mosque archives pushed up against the walls. They had recently been moved from the room over the Vestibule at the far south side of the western gallery.

The Deesis was not the first mosaic to be uncovered. The work began with the mosaic of Leo over the Royal Doors in the inner narthex; this was a smart move to start with the mosaic of Leo which was over the main door and was seen by anyone entering the church. The first incision into the plaster in the South Gallery took place on July 14, 1934. This season there would be work on the location of the Deesis, the Zoe panel and the mosaic of John II and Eirene. Later they planned to move downstairs to look for the Virgin and Child in the apse and uncover the mosaics in the South Vestibule. The first season of work took four months and ended in late November of the same year. The uncovering of the mosaic panels in the south gallery involved further conservation, consolidation and study, lasting through seasons of work in 1936, 1937, and 1938. It was a slow and deliberate effort. To some extent they were learning on the job using different methods to consolidate and clean them. They were in a very precarious state. As they uncovered the mosaic, they realized that were unveiling a something of world significance - this actually filled them with awe, and made them even more careful in their work on it.

The pictures that somehow got out caused quite a sensation in the press. The following is an excerpt from letter of Royall Tyler to Mildred Barnes Bliss, October 11, 1936 about seeing the Deesis for the first time. Royall was a world traveler and an advisor to Mildred Bliss on art purchases:

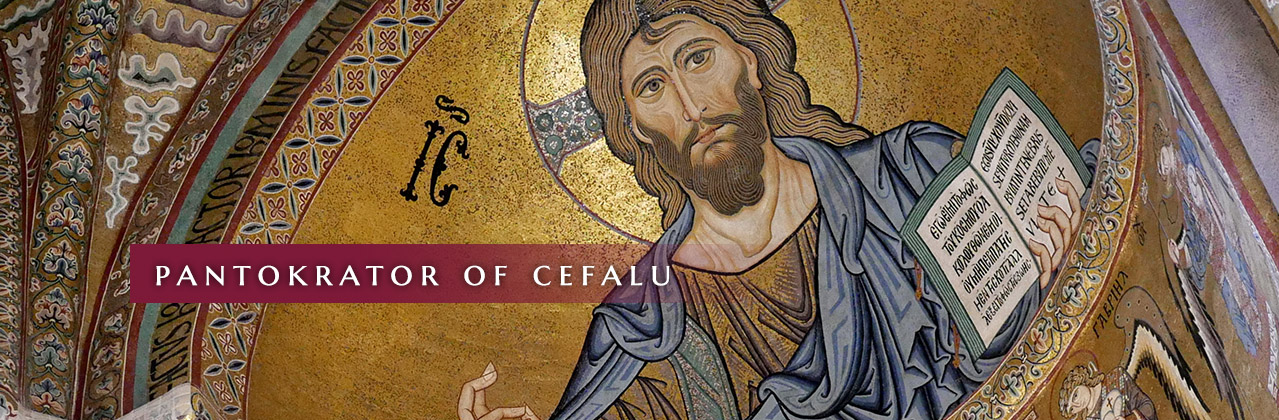

"The Deesis, also in the S. Gallery, has rather less left than the others, but it is a marvel of beauty—all 3 heads: the Christ, the Virgin and St. John Baptist. This is by far the most beautiful mosaic I’ve ever seen, and it shows where Daphni comes from, and the Sicilian mosaics. Its perfection and accomplishment, in drawing, colour and cube-setting, are amazing. Looking at it, I felt that if Rubens could have seen it, he’d have sat up and sneezed—It has all his lightness of touch and of colour, richness of impasto. Until one has seen that, one doesn’t know what XI cent. mosaic is. Even the Pródromos (St. John B.) at Daphni pales a bit before this Pródromos—tho’ it’s honourably near, and very grand."

The former King of England Edward VIII and Wallis Simpson were among the VIP visitors. On Saturday, September 5, 1936, guided by Whittemore Edward VIII fearlessly climbed up the apse scaffolding so he could see the Theotokos and the Archangel in the bema arch up close. The scaffolds in the apse were scary to climb on. Ernest Hawkins suffered from extreme acrophobia - fear of heights - so a special tunnel was made so he could get on the platform around the Theotokos. In 1946 he was called upon to make emergency repairs to the mosaics of the dome in a storm! The windows were being replaced during a gale and huge sections of gold mosaic were peeling off and moving around in the wind. At least one large section of mosaic fell into the nave. he must have been terrified to have to climb out onto the internal cornice of the dome.

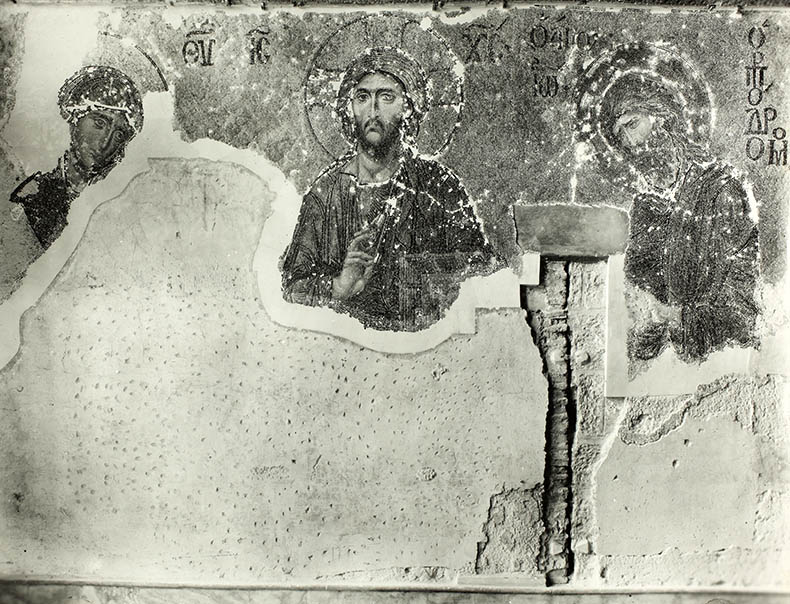

These files were stacked up in front of the mosaic when the work began. What a horror to see the damage done to the panel. This was done in 1910 when the Sultan ordered Hagia Sophia surveyed for potential weak spots or places where things were moving. There had been warnings that it could collapse at any time. Here they have exposed a crack in the pier. At the same time work was done in the dome.

The Deesis panel is 5.95m (19.5 ft) wide and 4.08m (13.5 ft) tall. The Byzantine Institute recorded everything with clear photos and copious notes so we are able to see exactly what happened in their journals. Below we can see the state of the mosaic midway through cleaning and consolidation. The painted plaster decoration above the panel was meant to imitate marble revetment is a 19th century restoration. The marble vine-leaf cornice above it is from the time of Justinian. There were two courses of Proconnesian marble at the bottom. The lower course was part of the original decoration of Hagia Sophia and the second, upper one was added to frame the mosaic panel. At some point after the mosaic was created, in the Byzantine period, this row of unmatched marble panels was put up to hide damage along the bottom of the mosaic.

Look at that crack in the wall to the right. In 1910, Sultan Mehmet V set up a commission of specialists to examine the fabric of Hagia Sophia. This cut was made to expose the line of junction between the brick and stone of the pier. They inserted glass epies to detect any settlement in the building. Unfortunately, a part of the mosaic was damaged in this process.

Above another picture showing a step in the process of the restoration - what a mess. Everything has been secured and the mosaic has been set in plaster beds. It shows you how difficult a job of conservation it was. One of the big challenges they faces was toning in the plaster so the white didn't show so starkly. After many tries, they actually made a wash of cobwebs

From 1847 through 1849 a complete renovation of the mosque of Hagia Sophia was conducted by Giuseppe and Gaspare Fossati at the command of Sultan Abdul-Medjit. During this renovation they discovered the Deesis panel and made a rudimentary watercolor record of it. During their work they made large repairs to parts of the plaster here. Finding the mosaic was in a perilous state and about to detach from the wall, they had little time to fix it and worked fast. In great haste to save the mosaic from dropping off the wall in front of their very eyes, they drove rough hand-wrought iron nails right into the panel and along the top to hold it up. That was invasive, but it saved the panel.

Above you can see the restorers with their tools - working on the bema Angel. The restorers were plagued by rats and birds who used to steal anything - even their tools right from under their eyes. They were especially attracted to their brushes.

Even though they had uncovered and recorded the mosaics at the express command of the Sultan, the intention was always to cover them again, since the building was a mosque and intended for Islamic use which prohibits representational imagery. First, they smeared a size over the mosaic tesserae that was extremely difficult to remove during the restoration, requiring dental tools and carborundum to get it off. Then the Fossatis covered the panel with several layers of plaster, increasing the depth from right to left to correct the slant of the wall. Finally the Italo-Swiss architects painted two horizontal bands imitating red and Proconnesian marble panels over the area to make it blend it with the rest of their decoration of the mosque. The watercolor sketch made by the Fossatis showed that in its outlines and masses the mosaic had not undergone serious material change since 1849. This was not true of the mosaic vaults of the South Gallery, however, which had mysteriously vanished since the Fossatis last covered them up.

Above is one of the first color pictures of the restored mosaic taken in the 1930's

As mentioned above, although the actual removal of plaster took only one year, further seasons of work were needed to consolidate and restore the mosaic.

That's Professor Thomas Whittemore on the left, working in the Kariye Djami. On June 8, 1950, as he was about to enter the conference room in the office of John Foster Dulles at the State Department in Washington, D.C., Whittemore suffered a heart attack and died at the age of 79. He is buried at Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, MA.

All of the Fossati, and earlier Byzantine ones, iron nails, which had become badly corroded, were extracted - one by one - and replaced with cramps of 'Delta' metal. Thin copper wires, now invisible, were used where necessary to secure the plaster bed and the mosaic

Publication of the discovery of the mosaic created a sensation in the art world. Never before had a Byzantine mosaic of this artistry been seen and the level of technique surpassed anything previously known. The mosaics went a long way towards redeeming Byzantine art in the view of art historians and public opinion, the art of Byzantium having been denigrated for centuries. The extraordinary quality of the Deesis and the stunning visual impression it made upon all who saw it, changed minds about the importance of Byzantine art, its originality and creativity.

In the beginning the mosaic was known only through black and white photographs, Fortunately, amazing reproductions of the mosaics were created, just in case Hagia Sophia was bombed in a war or destroyed by riot or earthquake. The first step was the production of tracings from the mosaics. The method was simple; tracing paper was attached to a section of mosaic and an assistant copied each tesserae exactly. These tracings were sent to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology to be photographed, blueprints backed on linen were produced and sent back to Istanbul where they were then painted in egg tempera by Alwyn A. Green, a young English artist who was in his twenties. These full-sized reproductions, paid for by the Robert and Mildred Bliss, among others, went on tour around the USA. One of them, the panel of John II Komnenos and Eirene, ended up at the Seattle Art Museum in Volunteer Park, where I saw it as kid hanging high up over a door to one of the halls. The copy of the Deesis was completed in 1946 and cost $7,500. It went on permanent display in the Metropolitan Museum in New York and is still on display there in the Medieval hall, where it is seen from the same distance it would have been viewed from the lower gallery at Hagia Sophia.

Castings were also made and hand-painted by George A. C. Holt of Bennington College, who invented the process and Alwyn (that's him below). A drawing of the Deesis was made during the summer of 1936 in 7 parts by Adli Bey - a Turkish architectural student. The drawing of the Zoe panel and the John panel was done by a Russian, Nicholas Kluge. The work of tracing the mosaics was tedious and took months to complete. In addition Kluge had eye trouble. Kluge also made all of the official notes on the mosaics in Russian which are online. Whittemore translated them and took credit for them in official publications of the Byzantine Institute. The drawings were not enough and George Holt took the castings himself.

Robin Cormack tells us that Ernest Hawkins, a Byzantinist who was originally a sculptor and the author of many of the reports published in this website and was working at Hagia Sophia at this time (beginning in 1938), and Whittemore were temperamental artists who had frequent disagreements. Green was born in Lancashire and spent his first years in Blackpool. In 1939 Alwyn was single and living in Chelsea, London where he worked as a mural artist and lived with a couple of church caretakers, Frank and Cecelia Axfel, who were in their 90's. Alywin's father died during WWI in 1917. Alwyn and Ernest remained close for the rest of their lives. As mentioned above Alwyn did the copy of the Deesis that's in the Met. George Holt arrived on June 2nd.

After being drawn in pencil on transparent linen, the tracings were sent to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology,where K.J. Conant photographed, backed them with linen and setback to Istanbul to be painted.

Green began and finished his painting of the Deesis on December 7, 1940. He imported his paints and gold leaf from America which were delivered to the American Embassy in Istanbul. The gold leaf was damaged in shipping and Green had to find it locally in the city. He used 40 books of leaf in the coloring of the Deesis. The Deesis was packed and Green returned home to England two days later. He returned to Hagia Sophia in 1946 and worked alongside Nicholas Kluge, now 77, in uncovering and conserving the Church Fathers in the tympana. They also supervised the final photographs of the Deesis that were to be used in the final report with Whittemore. He finished his painting of the John and Eirene mosaic in October. Nicholas Kluge died a year later on October 5, 1947. Alwyn Green lived until 1979.

These painted reproductions are a part of the legacy of the "Byzantine Boys" - as Green called them.

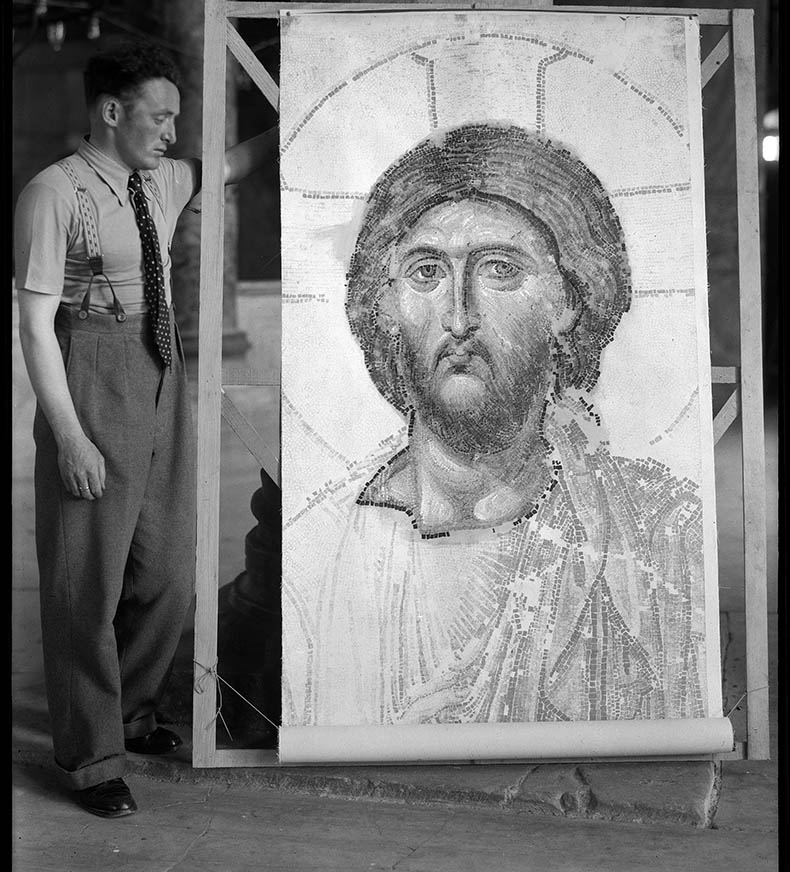

Above, here's Alywn Green holding one of the hand-colored molds they made of the mosaic - this gives you an idea of the scale of the figures. In 1944 the first ones were on display at the Met in New York. During the war the Deesis was sealed up and protected with wood. The painted molds and drawings were not completed until October 1947 and were shipped out at the end of the season. The Deesis was done in seven long strips of molding cloth. When he was hired by Whittemore Alywn was not a professional restorer, he was a mural painter. In the years he worked in Hagia Sophia he became involved in all aspects of conservation and restoration. All of the colored murals from Hagia Sophia were done by him. One of the advantages Alywn had was he was young and worked fast. Kluge was so slow at drawing the mosaics - it look him weeks to complete one strip. It turned out he had bad eyesight, but never told anyone. Perhaps this kind of work ruined his eyes.

As a sculptor Ernest Hawkins worked in a neo-Romanesque style, producing work for Westminster Cathedral (the staircase to the pulpit, added at the time of remodeling in 1934) and the screen to St. Patrick's Chapel. Hawkins joined Whittemore as a technical assistant in Istanbul in 1938. His motivation was apparently less scholarly than the need to make a living, he had no formal training as an art historian. After Whittemore died he had long career in Byzantine studies. Hawkins became an expert in the sourcing of historical pigments. He received an OBE in 1971.

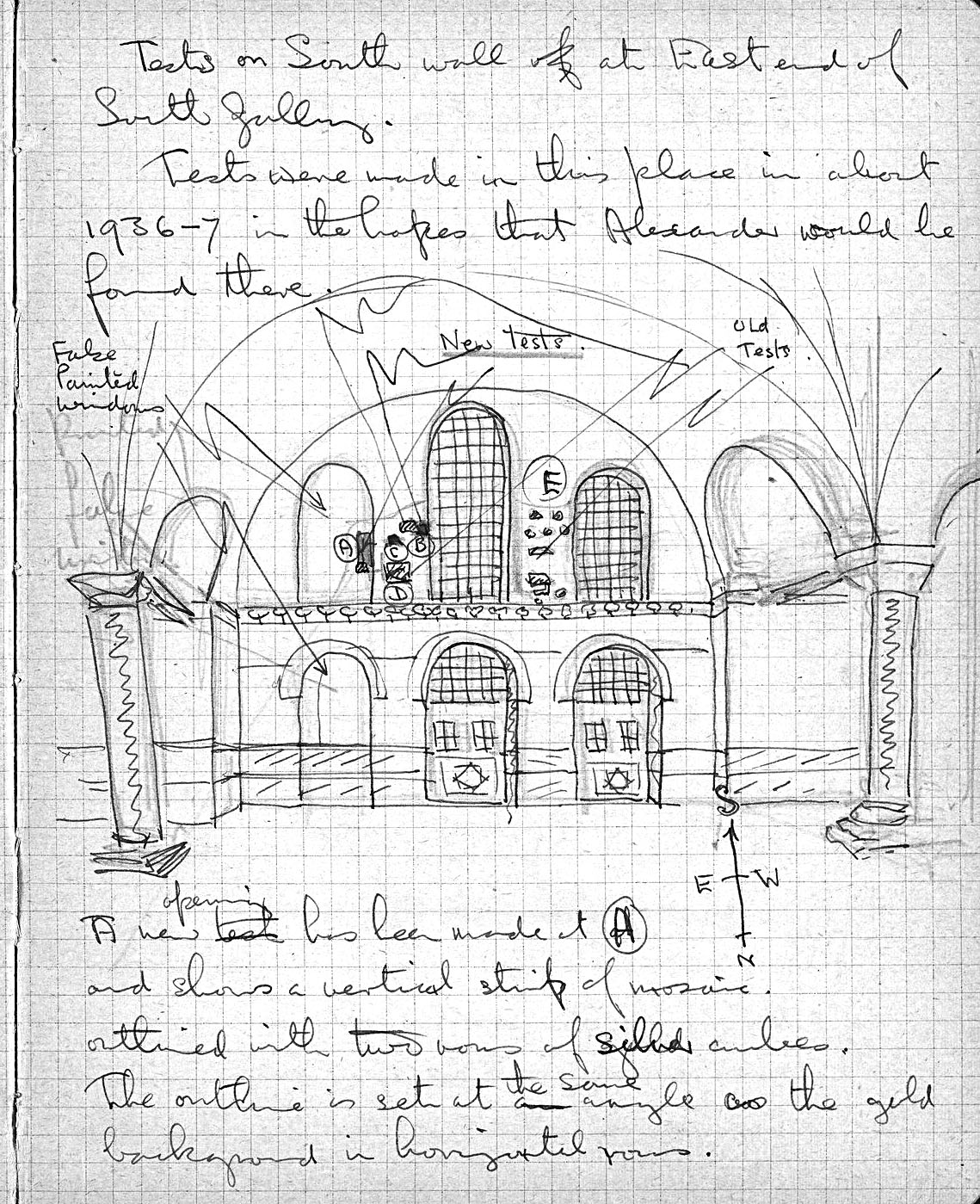

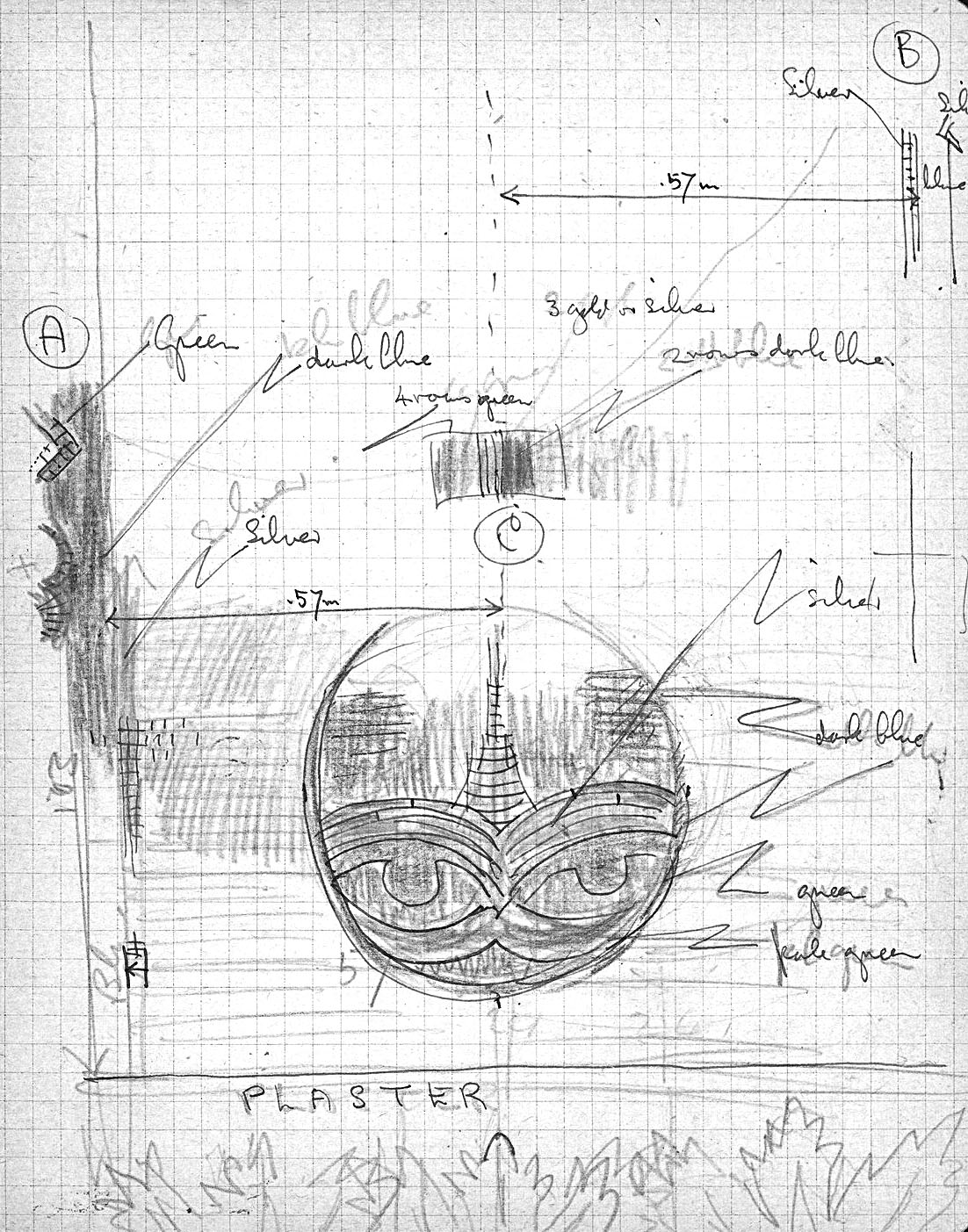

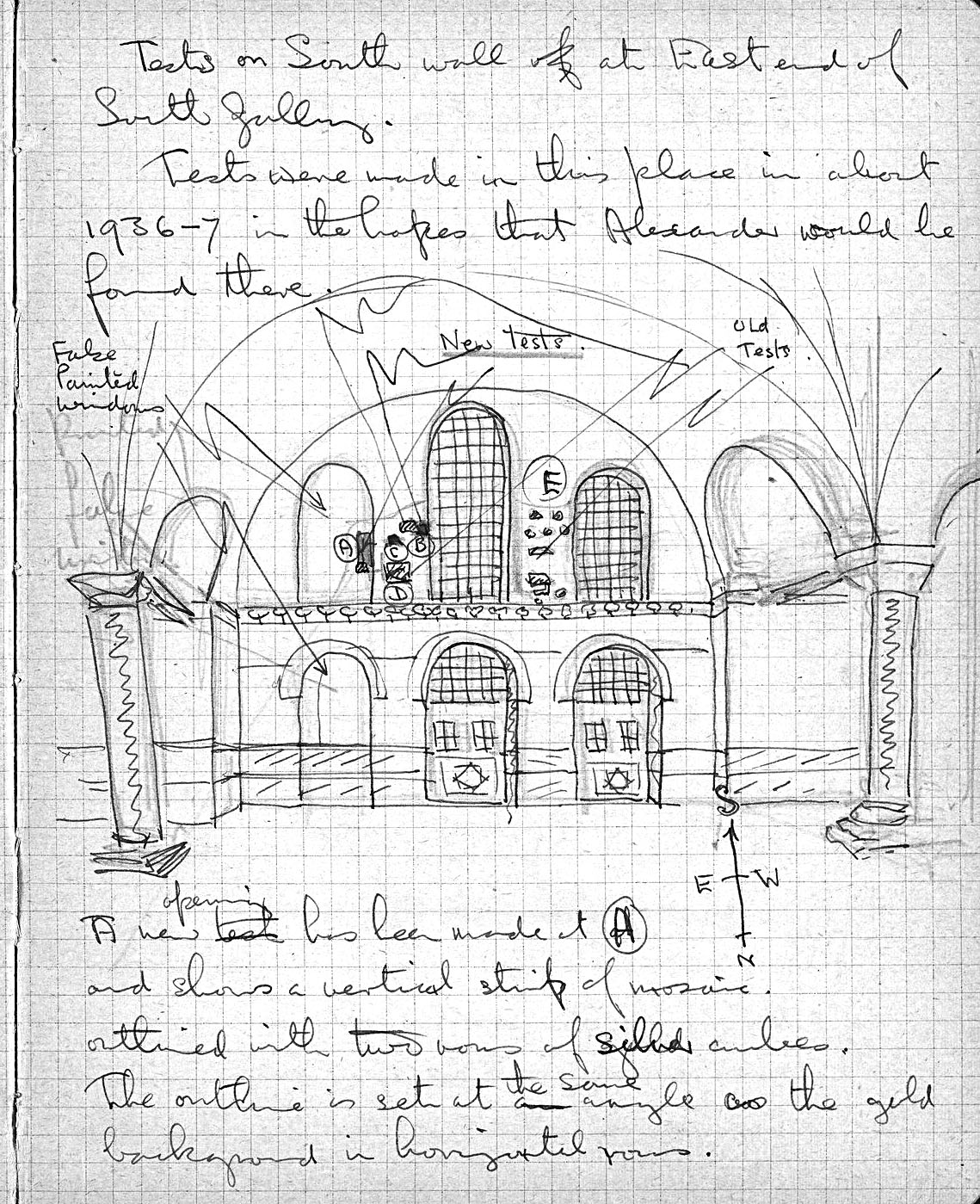

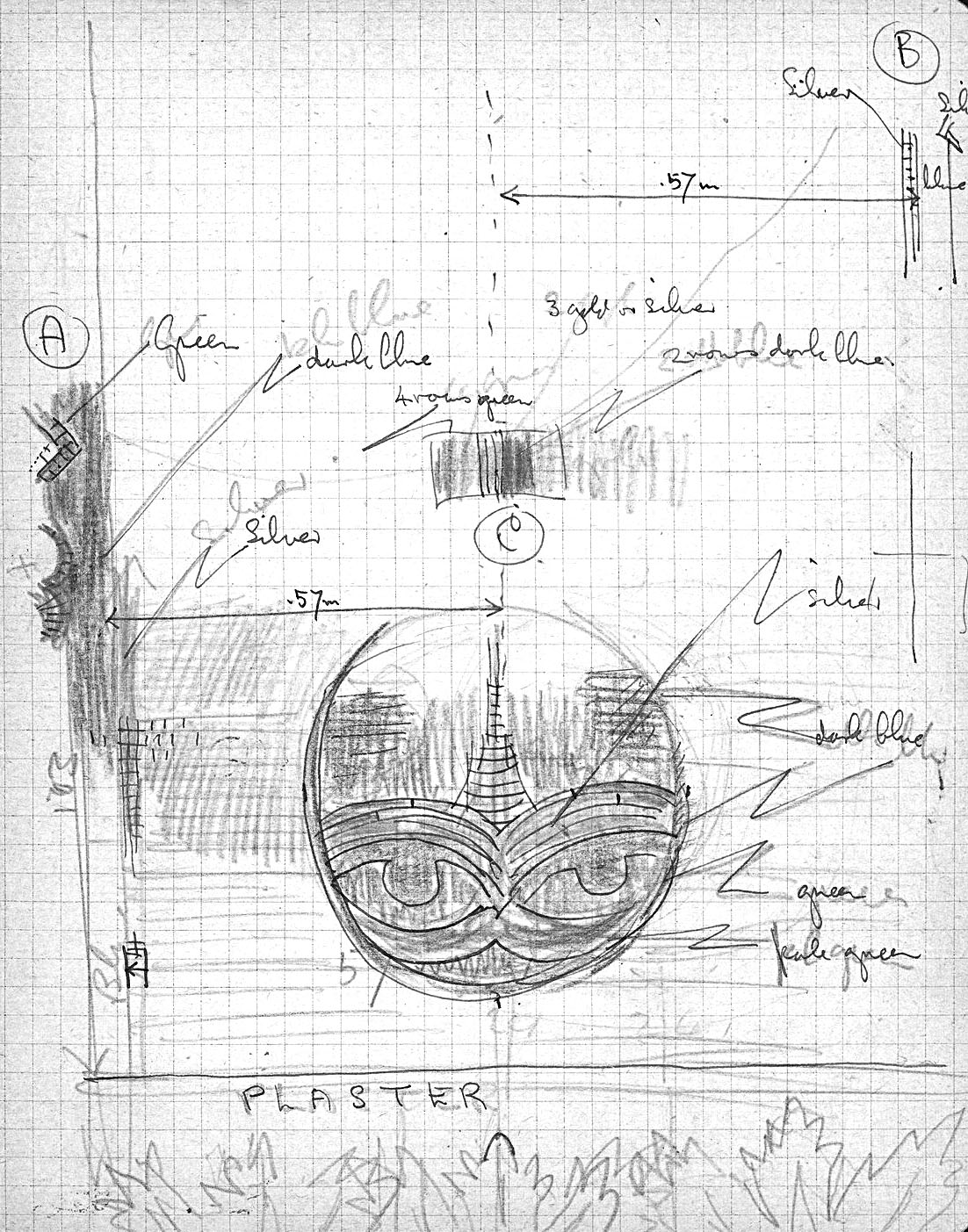

In 1950 Paul Underwood discovered that mosaic cubes had been taken from the Theotokos in the panel of John II and tesserae were missing from the Deesis. He discovered splinters of green and red mosaic cubes and plaster dust on the floor. Paul believed that the gold mosaic had been under constant attack by vandals. A piece of glass was put up to protect the Deesis from visitors who could not stop themselves from touching it. Later in the same year Paul discovered that two holes had been bored into the Deesis. As a result he recommended that a railing be put up in front of it. In the same year Paul made additional tests in the south wall of the east end of the South Gallery for new mosaics. They found some. I have never seen anything other than these notes that describes them.

Above are two pages from Paul Underwood's notebook for 19550 in which he describes what he found. There is more that I didn't put up. This page is already too long. I am not sure anyone will make it this far down!

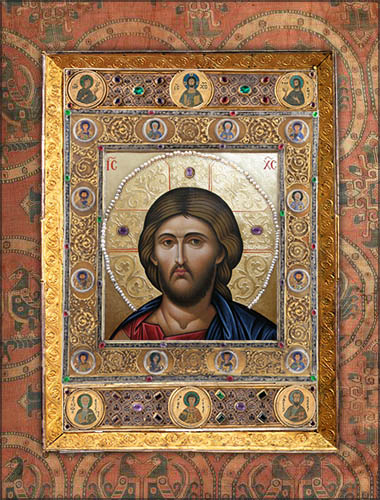

In the late 30's few people traveled to Istanbul to see the mosaics first-hand. During WWII the Deesis was covered to protect it from harm until after the war. The mosaic did not become popular and well-known until recently; thousands of tourists visit Hagia Sophia each day taking photographs and posting them places on the web. Today the Christ of the Deesis has become one of the preeminent images of Jesus in the world.

In 1948 the huge Islamic discs - which so disfigure the interior - were removed and the nave was photographed without them. It's possible they came down to protect them during the war or they needed restoration

The discovery of the mosaic was a sad reminder of how much of Byzantine monumental art has been lost over time. Thomas Whittemore was interviewed by magazines and newspapers around the world about the work of the Byzantine Institute in Hagia Sophia.

In 1942 Thomas Whittemore wrote about the his work on the mosaics for American Journal of Archaeology and described how they were uncovered. Here he writes specifically about the mosaic of the two Emperors over the door in the vestibule:

"The method used by the Institute is worthy of description. A steel scaffold was built, thirteen meters in height and moving on swivelled wheels on a steel track. It had two sliding floors which reached to the vault of the Narthex, but which were constructed so as to avoid its transverse ribs when the scaffold moved. Both floors were enclosed in canvas, and lighted and heated with electricity from the Mosque. After the mosaic area of the vaults and walls had been thoroughly studied and photographed, two experts undertook the task of cleaning. No solvents of any kind were used in removing the paint from the mosaics. It was flaked off, tessella by tessella, by means of a small steel chisel, like those used in cleaning fossils or in scraping varnish and overpainting from pictures. The old plaster reinforcement between the cubes was not touched, as it strengthened the tessellae without spoiling the effect of the mosaics."

The date of the creation of the mosaic is unknown. There are no surviving Byzantine writings that mention it and Byzantine artists usually did not sign their works - so we don't know the artist or workshop that created it. The only mosaic that has similarities to the Deesis is the small panel of Alexios that was added to the nearby mosaic of John II and his wife Irene just a few feet away.

Thomas Whittemore believed the mosaic dated from the late part of the reign of John II or the first years of his successor, Manuel I Komnenos. Whittemore felt the closest dated parallel to the Deesis was Our Lady of Vladimir, a famous icon which traveled from Constantinople to Russia in this period. He saw an unmistakable connection of the style and tenderness between the face of the Virgin in the Deesis mosaic and the icon. We can also see a connection in the Kahn Madonna in the National Gallery.

Above you can see the restorers working on the Church Fathers in the typana.

click here for icons of christ

click here for icons of christ click here for icons of the theotokos

click here for icons of the theotokos click here for icons of angels

click here for icons of angels click here for icons of saints

click here for icons of saints