Theodora - wife of Justinian the Great

The Empresses of Constantinople - Author: Joseph McCabe

THE EARLY LIFE OF THEODORA

The next Empress to occupy the superb apartments in the palace, with their couches of ivory and silver and their regiments of fawning eunuchs and silk-clad ladies, was assuredly one of the most remarkable figures that ever sat on a throne. The Empress Euphemia hardly ever issues into the pages of history from the becoming seclusion of the women’s quarters in the palace, but the few details which we have concerning her suggest the most incongruous figure that imagination could place in such a world, and a brief account of her romantic elevation is a necessary introduction to the equally remarkable and better-known story of the famous Empress Theodora. The Roman Empire seemed to be deterred by some faint recollection of its early democratic spirit from admitting the hereditary principle; but the absence of this arrangement for securing the succession, together with the complete lack of any really democratic arrangement, often threw it into a chaotic confusion when a ruler died, and made its internal history a thrilling succession of romances and tragedies, with an occasional page of comedy. In this case it is comedy.

Anastasius, after playing his successive parts as peasant, lay preacher, soldier and ruler of the world, had passed away, amid the derision and rejoicing of his people, in the year 518. His nephews had feeble pretensions to succeed him, but the most powerful man in the city, the Prefect Amantius, decided that the purple should pass to his friend Theocritus. He therefore sought the commander, or Count, of the Excubitors—the more formidable guards of the palace—and placed in his hands a large sum of money for distribution among the troops. Justin, the said commander, was an Illyrian peasant who had won promotion in the wars. He was in his later sixties, though still a powerful man, with handsome rosy face and curly white hair; but under this disarming exterior he concealed an ambition and astuteness which the prefect failed to suspect. He distributed the money in his own interest, and passed unopposed from the modest quarters of the guard to the more luxurious chambers of the palace.

Anastasius, after playing his successive parts as peasant, lay preacher, soldier and ruler of the world, had passed away, amid the derision and rejoicing of his people, in the year 518. His nephews had feeble pretensions to succeed him, but the most powerful man in the city, the Prefect Amantius, decided that the purple should pass to his friend Theocritus. He therefore sought the commander, or Count, of the Excubitors—the more formidable guards of the palace—and placed in his hands a large sum of money for distribution among the troops. Justin, the said commander, was an Illyrian peasant who had won promotion in the wars. He was in his later sixties, though still a powerful man, with handsome rosy face and curly white hair; but under this disarming exterior he concealed an ambition and astuteness which the prefect failed to suspect. He distributed the money in his own interest, and passed unopposed from the modest quarters of the guard to the more luxurious chambers of the palace.

Euphemia was the wife of Justin, and it may safely be said that no woman ever experienced a more romantic elevation. In his military days Justin had bought a barbaric slave named Lupicina, and raised her to the rank of his concubine; though no doubt he married her in the course of time. She retained the uncouth and illiterate manners of her class, and Constantinople must have smiled to see her in the richly embroidered robes of purple silk, with cascades of diamonds and pearls falling from her gorgeous diadem. The acclamation of the crowd changed her name to Euphemia, and she retired to the congenial privacy of her palace. Justin brought his equally illiterate mother Bigleniza to the palace from her rustic home, and the two women no doubt contracted a fitting friendship in their wonderful new home. Of public action on their part there is no question, and the events of the next few years do not concern us. I will say only that, after securing his throne by cutting off the head of Amantius and crushing Theocritus under heavy stones in his dungeon, for venturing to resent the trick he had played them, Justin ruled with moderation, if not prudence, for nine years. Euphemia died three or four years before him, living just long enough to see, and emphatically resent, her successor, the notorious Theodora.

In approaching the story of Theodora it is necessary to premise a few words on the authority which has provided most of the sensational statements about her, and to pay respectful attention to the efforts of some recent historical writers to discredit those statements. The general outline of her story has been made familiar by Gibbon, who has genially dilated on the elevation of one of the lewdest actresses and most notorious prostitutes of Constantinople to the position, not merely of mistress of the greatest empire of the time, but also of patroness of an important branch of the Church and the daily companion of saintly monks and bishops. Since Theodora is very commonly described by the chroniclers as at least equal in power to her husband, the great Justinian, and since the next most powerful woman in the Byzantine Empire at the time is assigned a similar origin to that of Theodora, the world has long reflected with amazement on this spectacle of the Roman Empire at the feet of two imperfectly converted prostitutes. Such a situation could not pass unchallenged before the more critical tribunal of modern history, and there are scholars who have rejected entirely the romantic story of the youth of Theodora. The majority of historians, including the two chief living authorities, Professor Bury and M. Diehl, regard the story as true in substance though unreliable in detail.

In approaching the story of Theodora it is necessary to premise a few words on the authority which has provided most of the sensational statements about her, and to pay respectful attention to the efforts of some recent historical writers to discredit those statements. The general outline of her story has been made familiar by Gibbon, who has genially dilated on the elevation of one of the lewdest actresses and most notorious prostitutes of Constantinople to the position, not merely of mistress of the greatest empire of the time, but also of patroness of an important branch of the Church and the daily companion of saintly monks and bishops. Since Theodora is very commonly described by the chroniclers as at least equal in power to her husband, the great Justinian, and since the next most powerful woman in the Byzantine Empire at the time is assigned a similar origin to that of Theodora, the world has long reflected with amazement on this spectacle of the Roman Empire at the feet of two imperfectly converted prostitutes. Such a situation could not pass unchallenged before the more critical tribunal of modern history, and there are scholars who have rejected entirely the romantic story of the youth of Theodora. The majority of historians, including the two chief living authorities, Professor Bury and M. Diehl, regard the story as true in substance though unreliable in detail.

The more romantic statements concerning Theodora are taken from a work that purports to have been written by the greatest contemporary historical writer, Procopius, but there are writers (such as Ranke and Bury) who regard the work as, at the most, a later compilation of notes left by Procopius, and in any case it is so envenomed in temper, and occasionally so reckless in statement, that it should be regarded with suspicion. The problem cannot be discussed at length here, but it is24 necessary to justify the large use I am about to make of the work (the “Anecdotes”) which bears the name of Procopius.

If it were true, as is sometimes said, that we had no authority for the impeachment of the character of Theodora beyond the “Anecdotes,” we should have to hesitate very seriously, but this is by no means true. Procopius (“On the Persian War”) represents her as playing a most unscrupulous part in the ruin of John of Cappadocia. Liberatus (a contemporary cleric) and Anastasius exhibit the Empress to us corrupting the papacy itself and deposing a venerable pontiff by the most cruel and flagrantly dishonest charges. Zonaras and other writers accuse her, not merely of avarice, as Mr Mallett says, but of the most heartless and unblushing corruption in feeding her avarice. There is every reason to regard Theodora, after her elevation to the throne, as a woman devoid of moral scruple. But we now have ample confirmation also of the story of her origin. The statement of an eleventh-century writer, Aimoinus, that Justinian took his wife from a brothel, shows, in spite of its wild inaccuracies, that some such tradition was found in European literature quite apart from the “Anecdotes.” But the publication in the nineteenth century of the writings of John, Bishop of Ephesus, has furnished a decisive proof. This Monophysite bishop and cultivated writer, who lived for years beside the palace of Theodora, and whose sect received the most imperial and incalculable benefits from her, speaks of her as “Theodora of the brothel”; and he uses the phrase in such a way as to intimate plainly that this was the name by which she was known in Constantinople before her elevation to the throne.7 Indeed, the fact that the author of the “Anecdotes” does not assail the25 chastity of Theodora after her marriage increases our confidence in his account of her earlier life; as he did not intend to publish his work—it was not published until 1623—it would have been just as easy to invent or collect legends about her after as before her marriage. On the other hand, the temper of the writer is so bitter and malignant that we must reserve our judgment in regard to the details of his strange narrative. He has gathered together every defaming rumour about Theodora and Justinian that circulated in Constantinople, even admitting nonsense obviously unworthy of a serious writer, and we cannot sift the true from the legendary. The source of his animosity cannot be determined. From the tone of his remarks on religion I gather that he was one of the many surviving pagans who were forced into outward conformity with the new religion, and, after giving formal praise in his historical works to Justinian and Theodora for the splendour of their reign, he relieved his soul, in this secret collection of notes, of the deep disgust he felt at the contrast between their characters and their professions and between the glamour and the misery of their empire. It must be remembered that the thoroughly Christian and very weighty authority, Evagrius, is just as severe on Justinian; there was in Justinian, he says, “something surpassing the cruelty of beasts,” and any prostitute could despoil a wealthy man by a false charge (say, of unnatural vice—a trick of Theodora’s) “provided she let Justinian share her vile gain.” It is the common teaching of the authorities that the Empress was worse than the Emperor.

If it were true, as is sometimes said, that we had no authority for the impeachment of the character of Theodora beyond the “Anecdotes,” we should have to hesitate very seriously, but this is by no means true. Procopius (“On the Persian War”) represents her as playing a most unscrupulous part in the ruin of John of Cappadocia. Liberatus (a contemporary cleric) and Anastasius exhibit the Empress to us corrupting the papacy itself and deposing a venerable pontiff by the most cruel and flagrantly dishonest charges. Zonaras and other writers accuse her, not merely of avarice, as Mr Mallett says, but of the most heartless and unblushing corruption in feeding her avarice. There is every reason to regard Theodora, after her elevation to the throne, as a woman devoid of moral scruple. But we now have ample confirmation also of the story of her origin. The statement of an eleventh-century writer, Aimoinus, that Justinian took his wife from a brothel, shows, in spite of its wild inaccuracies, that some such tradition was found in European literature quite apart from the “Anecdotes.” But the publication in the nineteenth century of the writings of John, Bishop of Ephesus, has furnished a decisive proof. This Monophysite bishop and cultivated writer, who lived for years beside the palace of Theodora, and whose sect received the most imperial and incalculable benefits from her, speaks of her as “Theodora of the brothel”; and he uses the phrase in such a way as to intimate plainly that this was the name by which she was known in Constantinople before her elevation to the throne.7 Indeed, the fact that the author of the “Anecdotes” does not assail the25 chastity of Theodora after her marriage increases our confidence in his account of her earlier life; as he did not intend to publish his work—it was not published until 1623—it would have been just as easy to invent or collect legends about her after as before her marriage. On the other hand, the temper of the writer is so bitter and malignant that we must reserve our judgment in regard to the details of his strange narrative. He has gathered together every defaming rumour about Theodora and Justinian that circulated in Constantinople, even admitting nonsense obviously unworthy of a serious writer, and we cannot sift the true from the legendary. The source of his animosity cannot be determined. From the tone of his remarks on religion I gather that he was one of the many surviving pagans who were forced into outward conformity with the new religion, and, after giving formal praise in his historical works to Justinian and Theodora for the splendour of their reign, he relieved his soul, in this secret collection of notes, of the deep disgust he felt at the contrast between their characters and their professions and between the glamour and the misery of their empire. It must be remembered that the thoroughly Christian and very weighty authority, Evagrius, is just as severe on Justinian; there was in Justinian, he says, “something surpassing the cruelty of beasts,” and any prostitute could despoil a wealthy man by a false charge (say, of unnatural vice—a trick of Theodora’s) “provided she let Justinian share her vile gain.” It is the common teaching of the authorities that the Empress was worse than the Emperor.

In point of fact, there is nothing implausible or improbable in the details of Procopius’s story of Theodora’s early life, and the judicious reader will merely make allowance for the rhetorical strength of its superlatives. Her father Acacius had been a keeper of the bears which were baited in the Hippodrome in the reign of Anastasius. The Hippodrome at Constantinople united the functions which at Rome had been divided between the circus, the theatre and the amphitheatre. Its chief attraction was the chariot-racing which provided the central and most thrilling sensation of Roman life.8 Between the races, however, there were contests with wild beasts in the arena, and there were the numerous nondescript performances which occupied the theatre at Rome—mimes (actors by gesture), clowns, acrobats, conjurers, etc. Acacius was bear-keeper to the “greens,” and, when he died, his widow promptly secured another partner and claimed the office for him. But the superintendent Asterius had sold the office to another man, and the shrewd widow appealed to the sympathy of the crowd by parading in the Hippodrome, the heads and hands of her three daughters crowned with the emblems of virginity. The “greens” jeered—possibly at the sight of the eldest daughter, Comitona, a loose girl of seventeen, dressed as a Vestal Virgin—but the “blues” received them with sympathy; a distinction which the pale and slender little Theodora would never forget.

In point of fact, there is nothing implausible or improbable in the details of Procopius’s story of Theodora’s early life, and the judicious reader will merely make allowance for the rhetorical strength of its superlatives. Her father Acacius had been a keeper of the bears which were baited in the Hippodrome in the reign of Anastasius. The Hippodrome at Constantinople united the functions which at Rome had been divided between the circus, the theatre and the amphitheatre. Its chief attraction was the chariot-racing which provided the central and most thrilling sensation of Roman life.8 Between the races, however, there were contests with wild beasts in the arena, and there were the numerous nondescript performances which occupied the theatre at Rome—mimes (actors by gesture), clowns, acrobats, conjurers, etc. Acacius was bear-keeper to the “greens,” and, when he died, his widow promptly secured another partner and claimed the office for him. But the superintendent Asterius had sold the office to another man, and the shrewd widow appealed to the sympathy of the crowd by parading in the Hippodrome, the heads and hands of her three daughters crowned with the emblems of virginity. The “greens” jeered—possibly at the sight of the eldest daughter, Comitona, a loose girl of seventeen, dressed as a Vestal Virgin—but the “blues” received them with sympathy; a distinction which the pale and slender little Theodora would never forget.

The mother, who is said to have come from Cyprus, either before or after the birth of Theodora, then pressed the fortunes of her daughters in the theatrical world. Comitona was already a mime (or actress without words) and, as was usual, a prostitute. The young Theodora presently began to attend her elder sister, and is said to have begun her career of infamy as she waited among the slaves and lackeys on the fringe of the Hippodrome. When she in turn became an actress, her pretty pale face, lithe figure and unrestrained gaiety and dissoluteness made her a great favourite. She stripped to the narrowest limit of decency which the very liberal law permitted, performed the most nearly obscene ribaldries27 which the Roman theatre allowed, and was pre-eminent for the abandonment of her gestures and movements; and in the hours of the night, when the wealthier patrons of the Hippodrome entertained themselves in perfumed chambers with the actresses and courtesans, Theodora was in the greatest favour.

It is absurd to say that this is to impute to Theodora “a moral turpitude unparalleled in any age.” It was the common turpitude of that age, of our age, and of every intervening age. The theatre, indeed, no longer admits the very broad licence which was admitted at Constantinople, but the performances which are ascribed by Procopius to Theodora are innocent in comparison with certain performances which may be witnessed, in semi-publicity, in very many cities of Europe to-day. Of Theodora’s private behaviour—that she practised both forms of unnatural, as well as natural, vice—one need only say that it is, and always has been, common to her class. An actress at that time meant a woman of loose conduct. The imperial decrees and the Church fully recognised this, and it is significant that one of the theatres—if not the one theatre—of Constantinople was called “The Harlots,” and is so named in an imperial document. Procopius is merely imputing to Theodora the common practices of loose women of her time and our own. And when, in later pages, we come to realise the fiery and unrestrained temper of the beautiful Greek, we can well believe that she was at that time one of the worst of her class.

Not less plausible is the next chapter in the life of Theodora. A wealthy official, Hecebolus, induced her to accompany him to the African province which he was to administer, and her very brief career at Constantinople came to a close. M. Diehl conjectures that this occurred in 517, in her eighteenth year, and that she remained a few years with Hecebolus. However that may be, she was, about the year 521, ejected from the governor’s house, and she passed to Alexandria, and thence to28 Antioch and the other cities of Syria and Asia Minor. It is most probable that this was the time when, either at Alexandria or Antioch, she became a convert to the Monophysite faith. The question of the true character of Christ had racked and rent the Eastern world, amidst all its ribaldry and vice, for two hundred years, and the burning issue at this time was whether the nature of Christ should be described as single or twofold; the Monophysites held that there was but one nature in Christ, and were bitterly opposed to the “Synodists,” or supporters of the orthodox Council of Chalcedon. It may seem incongruous to drag in so solemn an issue on so defiled a page of biography, but it is essential for the understanding of Theodora’s career.

According to Procopius, Theodora still practised her evil profession in the cities of Asia. For the next few years, however, there is much obscurity about her movements, and the biographer cannot proceed with great confidence. One eleventh-century writer represents that Justinian and the commander Belisarius chose their wives in a loose house in Constantinople; another equally remote and unreliable chronicler says that Justinian found Theodora living a modest life, supporting herself by spinning wool, in a small house under the portico—a very strange residence for a virtuous woman. I prefer still to follow the very plausible story (in substance) of the “Anecdotes.” At Antioch Theodora went in great distress to visit Macedonia, an actress who had influence with Justinian. It is hardly strained to conjecture that this was the real occasion of her introduction to Justinian; that she went on to Constantinople with a recommendation to him and was at once taken into his house. Beyond question she was his mistress for some years before he married her.

Justin had brought from Upper Macedonia, and educated in the schools of Constantinople, the favourite nephew who was to become the Emperor Justinian. At the time when Theodora came back to Constantinople,29 about the year 522, he approached his fortieth year: a handsome, wealthy and free-living bachelor, of fresh and florid complexion and the curly hair of a Greek. His reputation was somewhat sinister: his influence unbounded. In entertaining the populace on his elevation to the consulship in the previous year he had spent about £160,000, and had turned twenty lions and thirty leopards together into the arena. He was plainly marked for the throne. The pretty pale face and bright eyes and graceful figure of Theodora captivated him, and her experienced art enabled her to profit by the infatuation. Justinian lived in the palace of Hormisdas on the shore of the Sea of Marmora, and Constantinople would take little scandal at his connection with Theodora. Four or five years’ absence would have enfeebled the memory of her earlier career, and the zeal for the true religion—the Monophysite heresy, which she paraded from the moment of her connection with Justinian—would ensure the genial indulgence of the frivolous population. Justinian had her made a “patrician” (or noble), lodged her in his beautiful palace, and showered his favours upon her. It is at this point that Bishop John begins to describe his co-religionists appealing to the protection of “Theodora of the brothel” from all parts of the Empire.

There were two obstacles to marriage. Justin was feeble and senile, and little able or disposed to resist his nephew’s whims, but Euphemia strongly opposed the marriage until her death in 523 or 524. The more serious impediment was the standing law of the Roman Empire, that a noble could not wed a woman of ill-fame (an actress, tavern-girl or courtesan). Justinian afterwards removed this restriction, but it must have been in some way overruled by Justin, and many authorities believe that the first law in the Justinian Code on the point was really promulgated by Justin. A daughter seems to have been born before the marriage, possibly before the connexion with Justinian, as John of Ephesus confirms the statement of Procopius that Theodora had a marriageable grandson before she died (in 548).

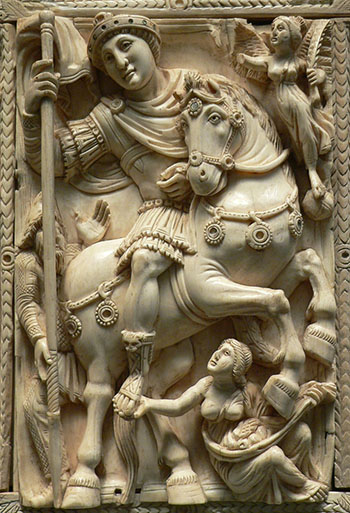

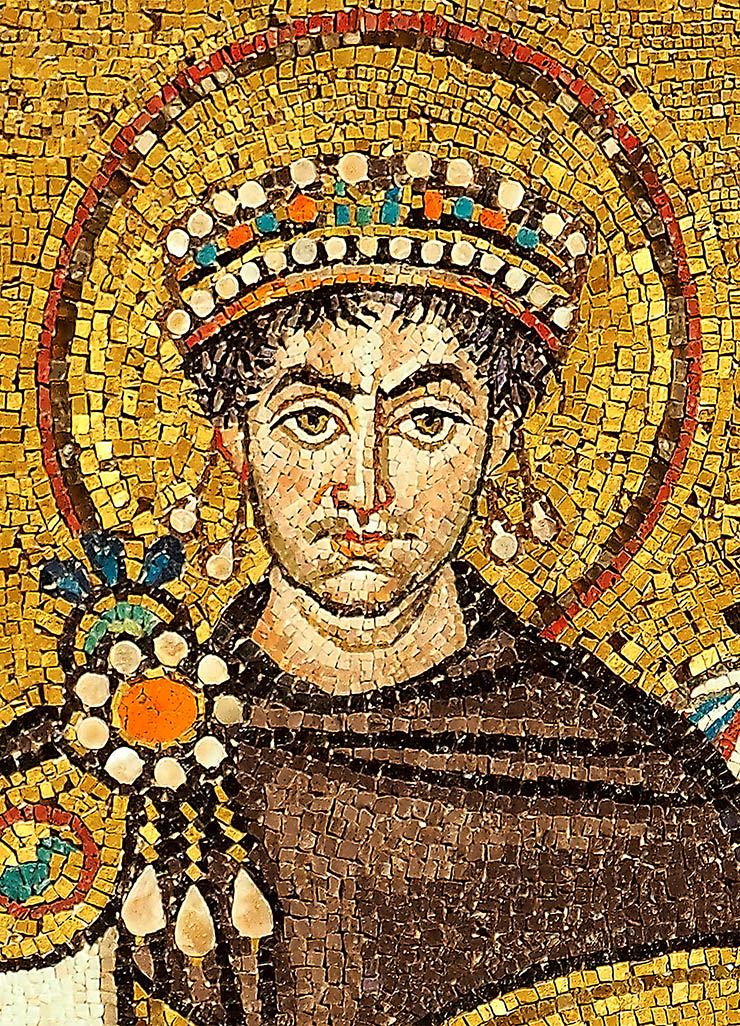

The next step for the enterprising young Greek was the attainment of the throne. Justin was pressed, as he aged, to associate his nephew in the government, and, although he nervously refused for some time, he at length (April 527) conferred the supreme dignity of Augustus on his nephew and of Augusta on Theodora. She now entered upon the full splendour of imperial life, and no parvenue ever bore it with more exaggerated dignity than the ex-actress, as we shall see. There must have been many who smiled when Theodora first witnessed the old sights of the Hippodrome from the imperial chapel of St Stephen, or sat for the homage of the Senators in the long gold-embroidered mantle, with the screen of heavy jewels falling in chains from her diadem upon her neck and breast, as we find her depicted in a mosaic at Ravenna; but her formidable power and her unscrupulous use of it would soon extinguish the last echo of her opprobrious nickname.

The early years of Theodora’s power were spent in enlarging the prestige of her position and in recompensing her friends. The existent palaces could not meet the requirements of the woman who, a few years before, had begged money of an Antioch courtesan. Justin had to annex his palace of Hormisdas to the imperial domain and build fresh palaces. The favourite residence of Theodora was the cool and superb palace of Hieria across the water, and in spite of the lack of accommodation for her enormous suite and the terrors of a whale, popularly named Porphirio, which infested the waters of Constantinople at the time, she frequently crossed to it.

At home, in the sacred palace, she led a life strangely opposed to that of the temperate, accessible and hard-working Justinian. Rising at an early hour she devoted a considerable time to the bath and toilet, by which she trusted to sustain her charm, in spite of delicate health. After breaking her fast, she again retired to rest before she would consent to receive courtiers and suitors. In view of her paramount influence with the Emperor many sought her patronage, or dreaded to incur her terrible resentment, by seeming indifferent to it. Numbers of nobles waited, sometimes for days, in the hot ante-room to her apartments, standing on tiptoe to catch the eye of the pampered eunuchs who passed to and fro. After a long delay they might be admitted to kiss the golden sandals of Theodora, and listen to her august wishes. No man was permitted to speak except in reply to a question. In the course of time, as we shall see, the highest nobles eagerly submitted to this humiliating treatment, in order to preserve their wealth from the extortioner. Dinner and supper, at which, though Theodora ate little, the most opulent banquets had to be served, occupied the further hours of the day, together with Theodora’s abundant devotions and converse with holy men.

Her friends were generously admitted to share her advantages. The “Anecdotes” tell a story of an illegitimate son of hers who discovered his birth, came to the Empress for recognition or money, and was at once despatched to another world. That seems to be one of the calumnious fables which the writer too eagerly admitted into his indictment. The “Anecdotes” themselves rather show that Theodora did not make every effort to conceal the past, however strongly she might resent discussion of it. Her sister Comitona was certainly married in the first year of her reign to a wealthy and powerful noble. It is not so certain, but probable enough, that she cherished her earlier theatrical friends, Chrysomallo and Indara, and found wealthy husbands for their daughters. The woman whose name we shall find most closely connected with hers, Antonina, the wife of the great general Belisarius, is said to have been her tirewoman before she married Belisarius. This would account for Theodora’s coolness until Antonina32 won her by securing her revenge on John of Cappadocia, when Theodora is said not merely to have overlooked, but promoted, the vices of her friend. There is, at least, no room for doubt about the character of Antonina.

But while Theodora admitted these mute reminders of her earlier life, she turned with extraordinary severity upon her earlier colleagues as a body and undertook the purification of the city. The decrees of Justinian for regulating the morals of Constantinople—decrees which go so far as to define the penalties for people who made assignations in churches, and on the strength of which bishops were castrated and exhibited in public for unnatural vice—are generally ascribed to her influence. She had the imperial net dragged through the loose houses of Constantinople, and five hundred of the occupants were imprisoned in an ancient palace on the Asiatic shore: a form of enforced piety which, the carping Procopius says, drove many of them to suicide. Many writers think this zeal for purity inconsistent with the story of her earlier life. It has rather the appearance of a feverish affectation of repentance, and must be balanced by the many proofs we have of Theodora’s really corrupt and unscrupulous character. One may recall that Domitian drastically punished the vices of others. Procopius would have us believe that Theodora compelled unmarried women to marry, and that when two delicate widows fled to the Church to escape her pressure, she had them dragged from the altar and married to men of infamous life. Yet, he says, vice was rampant in Constantinople, and protected by the Empress, when money was paid into her greedy coffers. Such details we cannot control, and must reproduce with reserve; we know only from other sources that she extorted money by corrupt means.

And the most singular and piquant feature of Theodora’s life at this period was her zealous patronage of the Monophysites. Long before her coronation, from the time when she became the mistress of Justinian, the joyous news of her elevation flew throughout the Empire among the persecuted heretics. They had had their hours of triumph under Basiliscus and Anastasius, but with the accession of Justin the orthodox had returned to power, and the twofold nature of the gentle Christ had been urged with bloody arguments. From the monasteries and towns of the provinces pilgrims now began to arrive at the Hormisdas palace in great numbers, and through Justinian she obtained relief and money for them. When she entered the imperial palace the procession increased, and, while the nobles of Constantinople were detained for hours before being permitted to kiss her feet, ragged monks and unlettered deacons strode into the imperial apartments without a moment’s delay.

So zealous, indeed, was Theodora for their edifying conversation that she kept them as long as possible about her. St Simeon of Persia came to plead the cause of his persecuted brethren, and was induced to live for a year in the luxurious palace. Arsenius of Palestine, one of the chief firebrands of his province, was cherished by her; though Procopius affirms that he at length lost her favour and was crucified. Orthodox monks were even permitted with impunity to rebuke the terrible Empress. A holy hermit came one day to chide Theodora for her heresy. Ragged and dirty, with garment so patched that hardly three inches of cloth of one colour appeared in it, he admonished her in fiery language. Theodora was so charmed with his piety that she sought to add him to her domestic collection of sanctities. When persuasion failed, she resorted to corruption; we read the story, not in the “Anecdotes,” but in John. She had a large sum of gold concealed in linen and imposed on him, but the fiery monk hurled it across the palace, crying: “Thy money perish with thee.” St Sabas, also, the unlettered and unadorned abbot of an orthodox monastery at Jerusalem, came to ask her patronage. His piety excused his heresy in her eyes,34 and she kept him for days at the palace, and humbly asked his prayers that she might have a son. The grim monk refused, and, when companions asked how he could scorn the request of so generous a patroness, he replied: “We do not want any fruit from that womb, lest it be suckled on the heretical doctrines of Severus.”

So great at length became the number of pious pilgrims from the provinces, and so eager was Theodora to retain them near her person, that the Hormisdas palace, which Justinian had richly decorated for her and enclosed within the area of the imperial palace, was converted into a monastery. Then were witnessed the quaintest scenes that ever enlivened the passion-throbbing palace of the Eastern Emperors. Five hundred monks, of all ages and nationalities, of every degree of sanctity and raggedness, were crowded in or about its marbled walls. Every form that monastic fervour had assumed in the fiery provinces of Syria or Egypt was exemplified in it. The orderly community sang its endless psalms and macerated its flesh in the rooms where Justinian had dallied with his mistress: little huts were scattered about the grounds for those who were called to the life of the hermit: and even columns were set up here and there for those who would imitate the more novel and arduous piety of St Simeon Stylites, and pass, at the open summit of the column, a kind of existence which the polite pen must refrain from describing. All the beggars of Constantinople gathered for the crumbs of this remarkable colony, and crowds of citizens pressed to witness this singular oasis of virtue in the most corrupt city of the world. Theodora rarely let a day pass without crossing the gardens to receive the blessing and enjoy the pious conversation of such of the saints as would deign to converse with a woman.

How she went on to put a courtly heretic upon the archiepiscopal throne of Constantinople, and, by an extraordinary piece of intrigue and corruption, depose a pope and replace him by one who pretended to favour35 her designs, we shall see presently. We must now set forth the imperial career of Theodora in chronological order, and learn what kind of character this remarkable woman maintained amid the chants and prayers of her deeply venerated monks.

THE EMPRESS THEODORA

We have seen how Theodora rewarded the friends, and must now see how she punished the enemies, of her earlier career. It will be remembered that her father had been a servant of the “greens” of the Hippodrome, but that this party had greeted her mother with derision when she appealed for sympathy with her three children, while the “blues” received them compassionately. Twenty years afterwards the young circus-girl had become the most powerful woman in the world, and the blues began to tyrannize with impunity over their rivals. In the earliest years of the reign of Theodora and Justinian we find them swollen with conceit and encouraged in the perpetration of every kind of disorder. The livelier “sparks” of that faction advertised their formidable character by adopting the trousers and sandals of the fierce Huns and trimming their hair after the fashion of those terrible invaders; they wore long moustaches and beards, shaved the front part of the head, and cultivated long hair at the back.

A few outrages soon taught them that the laws would not be enforced against them, and before long the city of Constantinople became, during the night, a land of terror. The citizen who dared to pass along the streets with a gold clasp to his belt or his cloak or money in his purse was robbed, and women could not move after nightfall. The continued silence of the authorities encouraged the blues, and drew all the dissolute elements of the city into their ranks. They now began to force37 the doors of the houses, plunder the coffers, rape the wives and daughters, and carry off the more handsome slaves and boys. At the least resistance their deadly poniards were drawn, and murder became frequent. When the authorities intervened, none but the greens were punished. The evil rapidly spread from night to day, and from the metropolis to other cities. It would be futile in this case to quarrel with the details given in the “Anecdotes.” The great riot into which the greens were stung by this reign of terror is an historical fact; and nothing but the vindictive memory of Theodora can explain how Justinian, the great legislator, permitted so appalling a disorder.

Theodora meantime enjoyed the conversation of her monks and hermits, and even Justinian seems to have been unconscious that he was slipping the leash of beasts whom he might be powerless to control. At length, on 14th January 532, the greens stirred. The Emperor appeared in his kathisma at the Hippodrome, and an appeal was made to him for justice. His officer replied disdainfully, and a long and curious conversation took place.9 The Emperor still refused to grant the impartial administration of justice or to punish the murderers, and the greens left the Hippodrome. They gathered in strength in the streets, and, although Justinian prudently sent to learn and partly to remove their grievances, they remained in arms. Belisarius was now sent against them with a troop of Goths, and the rioting and burning began. Unfortunately for the Court an accident then happened which had the singular effect of uniting the two factions against the troops. Seven criminals were to be executed, and Procopius cannot conceal the fact—in spite of his insistence that the blues were never punished—that some of the seven were blues and some greens. After five of the seven had been despatched, the rope broke, and the crowd demanded the acquittal of the remaining two. The authorities refused, and, as one criminal was a blue and the other a green, the factions turned in common anger upon the prefect and the troops.

The terrible riot that followed during four days must be read in history. The first part of the palace, the great church of St Sophia, and many other churches, mansions and public buildings were destroyed. Priests who rushed into the fray holding aloft the disarming emblems of their faith were cut down. On the fourth day, a Sunday, Justinian entered the Hippodrome with a Bible in his hand, and took a solemn oath to spare the offenders if they would disarm. “Ass, thou art perjuring thyself,” was the infuriated answer; and he retired to contemplate with Theodora the impending ruin of their reign. On the following day the crowd forced Hypatius, nephew of the Emperor Anastasius, to accept such purple robes as they could obtain, marched with him in triumph to the Hippodrome, and exulted in the downfall of Justinian and Theodora, who were believed to have fled to Asia.

The “great” Justinian makes a lamentable appearance throughout the whole riot, which he had guiltily occasioned, but Theodora and the abler ministers were not minded to yield. As they gathered in the hall of the palace, to which the cries in the Hippodrome must almost have penetrated, the chief eunuch Narses came to report that by a judicious distribution of money he had distracted the factions and weakened the cause of Hypatius. It is probably this news that turned the scale in the wavering counsels of Justinian and his ministers, but it was Theodora who pressed it home. The speech which Procopius assigns to her is worth reproducing, though we cannot regard it as more than a rhetorical paraphrase of the words she used:

“In my opinion this is no time to admit the maxim that a woman must not act as a man among men; nor, if she fires the courage of the halting, are we to consider whether she does right or no. When matters come to a crisis, we must agree as to the best course to take. My opinion is that, although we may save ourselves by flight, it is not to our interest. Every man that sees the light must die, but the man who has once been raised to the height of empire cannot suffer himself to go into exile and survive his dignity. God forbid that I should ever be seen stripped of this purple, or live a single day on which I am not to be saluted as Mistress. If thou desirest to go, Emperor, nothing prevents thee. There is the sea; there are the steps to the boats. But have a care that when thou leavest here, thou dost not exchange this sweet light for an ignoble death. For my part I like the old saying: empire is a fine winding-sheet.”

Some such sentiments, we may believe, were urged by Theodora, and affected the decision. The populace was penned in the Hippodrome, and Justinian’s officers and troops stealthily surrounded it. Rushing in at the various entrances, they fell with such fury upon the people that the sun went down on the corpses of between thirty and forty thousand citizens heaped in its arena or on the terraced seats.

The health of Theodora suffered from the strain of this terrible week, and she went to take the waters at the Pythian baths in Bithynia: a crowd of nobles and four thousand soldiers and eunuchs forming her retinue. Meantime Justinian set about the congenial task of re-erecting the Chalke (or front part of the palace), the church of St Sophia and the other ruined buildings, on a more splendid scale than before. We shall see later by what means he and his Empress obtained the prodigious sums of money they needed for their enormous expenditure. We will also postpone for a moment the40 early relations of Theodora to the general Belisarius and his romantic spouse, and consider the next important episode in which her character is seen.

In spite of the orthodoxy and religious zeal of Justinian, his wife had such influence over him and apart from him that in the year 535 she secured the see of Constantinople for the Monophysite Anthimus, to the unbounded delight of her sect and amidst the furious maledictions of the orthodox throughout the Empire. Rome was at that time regarded only as a sister Church of great authority and antiquity, but its venerable Bishop Agapetus was summoned to the Eastern metropolis and he succeeded in ousting Theodora’s favourite. Agapetus, however, died soon afterwards at Constantinople, and Theodora now conceived the bold design of putting a Monophysite pope upon the throne at Rome itself. For the remarkable events which follow I am not using the “Anecdotes” at all. The story is told in substance by a contemporary ecclesiastical writer, Liberatus the Deacon, of Carthage, and the chronicler Victor, and is repeated, with large and legendary additions, by Anastasius, the Roman librarian, of the ninth century.

In the suite of Agapetus at Constantinople was an ambitious and courtly deacon named Vigilius, who contrived to let his accommodating temper become known to the Empress. He was taken to her apartments, and he promised, if the Roman see and a large sum of money were bestowed on him, to reinstate Anthimus and the other Monophysite bishops. In the meantime the Gothic ruler of Italy had appointed a certain Silverius to the Roman see. Theodora tested him with a request that he would restore Anthimus, but he refused; murmuring, it is said, as he wrote the letter: “This will cost me my life,” as it did. The Byzantine general Belisarius had meantime taken and occupied Rome, and a few words must be said to introduce him, and his wife Antonina, into the story of Theodora.

I have previously mentioned an eleventh-century legend concerning Belisarius and Justinian and their wives. It was said that the two men had one day entered a house of ill-fame, found there two captive and fascinating Amazons named Antonia [Theodora] and Antonina, and married them. The myth seems to have crystallized about a belief that Antonina had risen from the same depths as Theodora, as the “Anecdotes” say, and the fact that Antonina was a woman of abandoned character and a leading lady in the service of the Empress seems to confirm this. In any case, she is openly assailed by Procopius (her husband’s secretary) in his historical works as “capable of anything,” and is described in the Lexicon of Suidas as “an infamous adulteress.” She had married Belisarius, and accompanied him in 533 on his brilliant campaign for the recovery of Africa from the Vandals. With them went a handsome and foppish Thracian youth named Theodosius. He was fresh from the baptismal font, in which the patriarch had washed away his Monophysite heresy, and it was believed that the presence of so sacred a youth would bring luck to the fleet. Before they reached Carthage Antonina enjoyed the secret love of the youth, but a servant betrayed them, and Theodosius fled to Ephesus, where we must leave him for a time. It is said that Antonina had the servant’s tongue cut out.

Belisarius passed from the subjugation of North Africa to a victorious war in Italy, and he and Antonina were staying at a palace on the Pincian Hill at Rome when the deacon Vigilius—now, no doubt, a priest—came with the commands of Theodora. “Trump up a charge against Silverius, and send him to Constantinople,” the order ran, according to the Roman librarian, and as the more authoritative Liberatus affirms that the charge was false, and was supported by mendacious witnesses and forged letters, there is no possibility of freeing Theodora from this grave imputation. The Pope was summoned to the palace, where Antonina lay on a couch with Belisarius42 at her feet. Antonina at once charged him with treasonable correspondence with the Goths. We may or may not believe the picturesque version of Anastasius: that the servants at once stripped the Pope of his robes, dressed him as a monk, and interred him in a distant monastery. It is certain, at least, that Silverius was, at Theodora’s command, deposed on a false charge and thrust out of sight. Vigilius became Pope, and the fate of Silverius is unknown to history.

I cannot entirely omit a later sequel to this sacrilegious and unscrupulous deed, though it rests only on the feebler authority of Anastasius. For a few years Theodora demanded in vain that Vigilius should fulfil his promise. He had, he said, come to see the heinousness of such a promise, and could not discharge it. In 544, therefore, Theodora sent an officer to Rome with a command which Anastasius gives in these words: “If you find him in the church of St Peter spare him, but if in the Lateran or the palace, or in any other church, put him on ship at once, and bring him to us. If you fail, I will, by Him that liveth for ever, have your skin torn from your body.” It is known, at least, that Vigilius was shipped away from Rome at the end of 544; but that he was at once taken to Constantinople, and that Theodora had him dragged through the streets like a bear, is untrue. He reached Constantinople after her death. We cannot therefore follow the deposition of Vigilius as confidently as we follow the sordid story of his elevation, but we can have little doubt that Theodora punished him.

Another authentic episode of the time reveals the same unscrupulous disdain of principles in the patroness of the Monophysite sect. The story is told by Procopius, not in the “Anecdotes,” but in his open and authoritative work “On the Persian War,” in spite of his usual extreme care to suppress offensive details. The Prefect of Constantinople, John of Cappadocia, had incurred the bitter hostility of the Empress. The very43 unattractive portrait which Procopius supplies, and Gibbon reproduces, of John prevents us from thinking that in this case an innocent man was persecuted. While he freely promoted all the schemes of Justinian and his notorious steward to wring money out of the citizens—“by fair means and foul,” as Zonaras says—he levied his private tithe on all their gains, and was popularly believed to indulge in secret the most sensual tastes and the even worse abominations of some pagan cult. He seems to have been the one man to regard Theodora with open disdain, and she retorted with venomous hate. Although guards surrounded his bedroom, he started every hour from his feverish slumbers to look for the expected assassin.

His value to Justinian enabled him to keep his position until the year 540, when Belisarius and Antonina returned from Italy to Constantinople.10 Antonina remained in the city while her husband went against the Persians. She feverishly summoned her Thracian lover from the monastery in which he hypocritically lingered at Ephesus, but the wrath of Belisarius held him aloof. Whether or no Antonina then deliberately sought the intervention of the Empress, we cannot say, but she proceeded to merit it. She learned of Theodora’s hatred of John, and conceived a plot for his destruction.

John had an ingenuous and amiable daughter who seems to have been not unacquainted with the political situation. Twice had the brilliant Belisarius been withdrawn to the city in a fit of jealousy, and there were rumours that the strong man was wearying of serving an Emperor who could do nothing but employ others and reap their glory. Antonina won her way to the heart and confidence of the girl, and betrayed to her that44 her husband was secretly disaffected. The artless Euphemia hastened to tell her father that there was a prospect of overthrowing Theodora, whom they both hated. Even John was deceived by the astute adventuress. It was arranged that Antonina should go to her suburban palace and meet John there during the night. We do not know that Theodora had a share in framing this diabolical plot, but it was now communicated to her by Antonina, and she at once pressed it and used her resources for carrying it out with safety. In the dead of the following night John entered the palace of the unscrupulous adventuress and listened to her whispers of treachery. Procopius says that Theodora had initiated the Emperor to the plot, and he had consented, but at the last moment sent a messenger to John not to see Antonina. This seems to be a piece of polite fiction in the interest of the Emperor; it is incredible that an astute and experienced minister would risk his neck after such a message. John went, and, in the apparently lonely palace, spoke his secret sympathy with the supposed design of Belisarius. No sooner had he uttered the words than a troop of imperial guards entered the room to arrest or assassinate him, but John also had brought soldiers and they enabled him to escape.

Had John gone straight to the palace of Justinian, he might still have saved his position. Instead, he fled nervously to the sanctuary, and Theodora hardened the mind of her husband. The wealthy and powerful noble was stripped of his estates and forced to enter the ranks of the clergy—one of the quaintest penalties of the time—in the suburb of Cyzicus. There the people whom he had oppressed might behold their once powerful enemy, the secret pagan and Sybarite, shaven and humiliated. It appears that Theodora was not yet satisfied, though she is not directly implicated by Procopius in the last act of the tragedy. The Bishop of Cyzicus was murdered, and as John was one of his many bitter enemies, he was arrested, scourged, and driven into exile and poverty.45 The fate of the unhappy Euphemia is unknown; she was probably compelled to enter a nunnery and weep there over the memory of the imperial tigress and her friend.

This story of perfidy, corruption and vindictiveness, which Procopius tells openly in his historical work, disposes us to believe the sequel, as it is narrated in the “Anecdotes,” even if we must regard certain details of the narrative with reserve. There was with Belisarius in Persia a son of Antonina by a former husband (or lover) of the name of Photius. Bitterly ashamed of his mother’s conduct, he accepted from Belisarius the charge of watching her lover Theodosius. At Ephesus he learned that Theodosius was in Constantinople, and soon caused him to fly back to Ephesus and cling to the altars which had sheltered so much vice and crime since the law of sanctuary had been established. The prelate, however, delivered Theodosius to the youth, and he was imprisoned in Cilicia.

Theodora was now eager to reward her friend and she had Photius arrested and scourged. He refused to reveal the prison in which he had placed Theodosius, but an officer was bribed to betray the secret, and the Thracian was brought to Theodora’s apartments. Theodora then sent for Antonina and said: “Dear patrician, yesterday there fell into my hands a gem finer than any that mortal eye has ever seen; if you would like to see it, I will show it to you.” Procopius concludes this astounding story by saying that Photius was kept for four years in the Empress’s underground dungeons. Twice he escaped to the church of St Sophia, and twice he was dragged back; at length he got away from Constantinople and hid from the vindictiveness of Theodora in the robes of a monk. There are writers who flatly refuse to believe this statement, though the authentic actions of Theodora which we have described lend it some plausibility. Once more, however, the recently published works of the contemporary Bishop of Ephesus supply some confirmation. We read in them that46 Photius, son of Antonina, “became a monk for some cause or other”; but the pathos of Gibbon’s picture of his fate is somewhat lessened when we read that he still enlivened the monastic life with his genial soldierly vices and led the troops to the plunder of the southern provinces.

I have mentioned the underground prisons of Theodora. Since it is from the “Anecdotes” alone that we learn of these dungeons, we should regard the statements with some reserve, and in this case there is additional reason for reserve. As Gibbon says: “Darkness is propitious to cruelty, but it is likewise favourable to calumny and fiction.” Procopius seems to know too much of what passed in these carefully guarded places. Theodora doubtless had spies everywhere, and it would be easy enough for her to have her enemies conveyed into the palace during the night, or to some prison in remote provinces. Somewhere about this time (541), we learn from John of Ephesus, her episcopal friend Anthimus incurred the anger of the Emperor and disappeared. John assures us that Anthimus was hidden in the Empress’s apartments for seven years. The two chamberlains who waited on him alone knew the secret, besides Theodora, until the day of her death. A woman with such resources could easily maintain private dungeons if she willed, and we can hardly say that it would be inconsistent with her character. But when Procopius minutely describes the fetid condition of these prisons, and tells how fiercely the prisoners were scourged, or how cords were tightened round their heads until the eyes started from their sockets, we are disposed to think that he has hastily admitted popular rumours which the judicious historian must set aside as unauthoritative.

On the other hand, a set of grave charges which Procopius combines with these statements are not without very serious confirmation. His most persistent charge against Justinian and Theodora is that they47 extorted money by cruel and flagrantly dishonest means. The superb buildings—the new palace, the new St Sophia, etc.—with which Justinian adorned the city absorbed stupendous sums of money; and the personal luxury and religious munificence of Theodora were such that a vast fortune would be needed to sustain them. It is equally certain that the money was largely raised by corrupt means. I have quoted the monastic writer Zonaras saying that Justinian raised money “by fair means and foul” and by “dishonest practices”; and the weighty testimony of Evagrius that the Emperor was of such “insatiable avarice” that he would share the “vile gain” of loose women impeaching wealthy men on false charges. The most that we can say for Justinian is that the money was not spent in personal luxury, and that it was extorted by subordinate officers. Agathias, another good authority, tells us how the steward Anatolius used to forge or suppress wills, and practise other dishonest arts, so that he might affix to houses and estates the strip of purple which betokened that they had become the property of the Emperor.

It is indisputable that the metropolis and the provinces suffered a most unjust and corrupt spoliation in order to sustain the splendour of the reign of Justinian and Theodora. Now Zonaras declares that the Empress was “worse than Justinian in extorting money, both by unlawful and lawful means,” and that she was “especially ingenious in finding ways” to enrich herself. Wealthy men had charges of secret heresy or unnatural vice brought against them, and their fortunes passed into the coffers of Theodora. This must mean that her servants, as the informers, claimed for her the legal share of the confiscated property which went to an informer.

Here again, therefore, the charges in the “Anecdotes” are substantially confirmed. Not content with securing testaments in her favour, she had them forged or altered. She suborned witnesses to support charges of vice or48 heresy. The only difference from Zonaras is in the added allegation of physical cruelty, and on this point Procopius is at times explicit. A member of the blue party, Bassus, a refined and delicate youth, issued some squib upon the Empress, possibly referring to her early career. He was dragged from the church in which he had taken refuge, charged with and convicted of vice, and subjected, before an indignant crowd, to the barbaric mutilation with which such vice was then punished. His property went to Theodora—in part, I assume, for laying information. Usually it was the greens who suffered. So angry were the people that they accused Theodora of a secret (but “impotent”) love of the sinister Syrian financier, Peter Barsymes, who had succeeded John of Cappadocia in the duty of governing and exploiting Constantinople. The restraint with which Procopius represents her love as “impotent” lends credit to his other charges. An accusation of an actual liaison would have been more credible than some of the stories he reproduces.

A few episodes remain in the career of Theodora from which we may confirm our impression of her remarkable personality. Unfortunately, they rest entirely on the authority of the “Anecdotes,” and cannot be pressed; we know only from another, and a sound, authority that Belisarius was maliciously attacked and disgraced after his many brilliant campaigns on behalf of the Empire.

To the evils of oppression, spoliation, corruption of justice, and persecution which afflicted the Eastern Empire under Justinian and Theodora there was added in the year 542 the deadly scourge of the plague, and for several years in succession it scattered the seeds of death over the broad provinces. Justinian at length contracted it, and became dangerously ill. As he had no son, the question of the succession to the throne was very naturally discussed, and the generals Belisarius and Buza in the Persian camp incautiously expressed themselves on the rumour that Justinian was dying, or were represented49 to the Empress by her spies as having done so. She at once ordered them to Constantinople. Buza is said to have been lodged in her underground prisons, and Belisarius was stripped of his rank, his guard and his immense wealth. A eunuch was sent by Theodora to secure the large sums he had deposited in the east, and the chosen soldiers who formed his personal guard, and were maintained at his expense, were distributed among the army. The greatest soldier that the Eastern Empire ever possessed, the most brilliant contributor to the success of Justinian’s reign, a man who had preserved his loyalty in a decade of supreme military power, he was received at the palace with cold haughtiness, and retired in deep distress to his mansion. When at length he observed the approach of a servant of the Empress, he prepared for death. Instead of death, however, Theodora’s officer brought this extraordinary message: “You know what you have done to me, Belisarius, but I forgive your crimes on account of what your wife has done for me. Hope for the future through her, but know that we shall hear how you bear yourself to Antonina.” And the episode closes with the great soldier kissing the feet of his perfidious wife, vowing that he will be her slave, and accepting the office of master of the stables in the imperial service which he had so gloriously illumined. Theodora had secured an enormous sum of money and intimidated an enemy.

Up to the last year of Theodora’s life (548) the implacable writer of the “Anecdotes” pursues his record of her misdeeds. Ever attentive to the men who might some day dislodge her and her relatives from the palace, Theodora watched with especial jealousy the grave and distinguished nephew of the Emperor, Germanus, and his three children. His eldest daughter Justina was in her nineteenth year, yet none had dared, out of fear of Theodora, to offer marriage to her. Theodora then decided to unite the fortunes of the two houses, and secure the succession, by commanding Justina to wed50 her grandson Anastasius—obviously the son of an illegitimate daughter of the Empress, since it was little over twenty years since her marriage to Justinian. Justina refused, and was vindictively married by the Empress to a common officer. She then commanded the daughter of Belisarius, Joannina, to wed Anastasius. Procopius, forgetting that he has stripped Belisarius of almost all his wealth (an exaggeration), says that Theodora wanted in this way to secure the general’s fortune, but we may assume that Theodora was mainly endeavouring to secure the succession to the throne for her grandson. Her own health was delicate, and Justinian was well over sixty. Belisarius shrank from the union, and even Antonina seems to have refused to further it. All knew that a struggle impended between the families of Justinian and Theodora, and it must have been the general feeling that the former would win. Theodora is said to have angrily united Joannina to her grandson in the loose popular form of marriage; indeed later rumour said that she had the young woman violated first.

Another matrimonial interference of the Empress in her later years exhibits the better features of her character. An ambitious general, Artabanes, sought and obtained the hand of Justinian’s niece, whom he had delivered from peril in Africa. Soon afterwards, however, a woman appeared who claimed that she was the legitimate wife of Artabanes. She appealed to the Empress, and Theodora forced Artabanes to take back his humbler wife. Procopius tells this story in one of the historical works in which he was careful not to offend the ruling powers, and he courteously adds that “it was the nature of Theodora to befriend afflicted women.” It is the only instance of her doing so that has reached us, and, ungracious as it may seem to cast a doubt upon the pure humanity of that one recorded good deed, one is compelled to suggest that it was not to her interest to see a niece of Justinian married to a successful commander.

On the 29th of June 548, after a reign of twenty-one51 years, Theodora died of cancer. Her body was embalmed and exposed for public veneration in the golden-roofed Triclinon of the palace. There, still dressed in the imperial purple, still bearing the magnificent diadem for a few days, she lay on a golden bed for friends and enemies to gaze upon the last state of one of the most remarkable personalities of the time.

The character of Theodora must be interpreted in so purely oriental a sense that it is difficult for the modern European to understand it. Whether Greek or Syrian in origin, she was an incarnation of the spirit of the great metropolis in whose life Syria and Greece were so singularly blended. It is useless any longer to cast doubt upon her earlier career. She was reared in that old theatrical world in which moral restraint was wholly unknown; and her beauty, vivacity and nervous strength make it probable enough that she was distinguished in it for dissoluteness. That in her later life she spent vast sums of money on the Church and philanthropy is unquestionable; nor would I doubt for a moment that she was perfectly sincere in her endless conversations with holy men. But her passionate nature, difficult position and supple intelligence gave her a genius for casuistry, and she fell into vices far worse than the vices of her youth. Quite apart from the attacks of her bitter, anonymous enemy, we have ample evidence that she was vindictive, cruel, unscrupulous, dishonest and callous. To send a bejewelled cross to the holy church at Jerusalem, or build a monastery, she would ruin and despoil an innocent man or wreck the happiness of a woman: to secure the preaching of the true faith in Christ she would depose an upright Pope on forged evidence and put a scoundrel in the most sacred chair in Christendom. It was the temper of Constantinople—to rise from vice and folly to defend the doctrines of the Church and enforce them with the dagger or the torch. The further things that are said of her in the famous “Anecdotes” must, for the serious historian, remain unproved but not improbable.

click here for icons of christ

click here for icons of christ click here for icons of the theotokos

click here for icons of the theotokos click here for icons of angels

click here for icons of angels click here for icons of saints

click here for icons of saints