Ikon History - Twilight of Byzantium

In 1204 the Latin soldiers of the Fourth Crusade diverted from the Holy Land and instead attacked the city of Constantinople. During the siege of the city fires purposely set by the Latins in an attempt to breach the wall defenses spilled into the city. The fire burned for days, spreading its way like a serpent through a large part of Constantinople. Since the city was, like ancient Rome, built on seven hills, and the fact that most of the poorer neighborhoods where built of wood, the fire grew to enormous size very quickly. No one had ever seen such a calamity. The resulting loss of art, architecture and literature placed the fire on par with the infamous burning of the Library of Alexandria. Many of the great works of classical art, which had decorated the streets of the city were consumed by flames or melted down for base coinage after the city fell. Untold thousands of books, paintings and other treasures, from over 1600 years of Hellenic and Roman culture were lost forever. No one thought it was possible. For the first time Constantinople had fallen to a foreign army. Even though the Latin Soldiers were supposed to be fellow Christians, they despised the Byzantines as heretics because they did not consider the Roman Pope to be the supreme head of the church and followed practices which were slightly different from those back in the Catholic world. Also, they considered the Byzantines effeminate because they took regular baths, read books and loved art. The city was devastated during the Crusader sack, and immense quantities of rare fabrics, gold, silver and gemstones, looted from the churches and palaces of the city were piled up and shipped off to the West. Many art works followed, including the four famous gilded horses from the Hippodrome which decorate the facade of St. Mark's Cathedral in Venice.

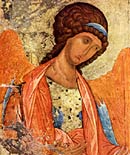

Thousands of Greek refugees, harassed by bands of Crusaders along the way, poured out of Constantinople for safety in the Balkan states, Greece and Asia Minor. Artists were included in this exodus and they took their skill with them. Greek empires were created in Nicaea, Trebizond and Arta. At these courts, especially at Nicaea, the arts flourished under the patronage of Greek rulers who were anxious to create their own, much-reduced, Imperial courts. A new style of Byzantine Art emerged in these cities the Balkans. The ikon at top left of the Archangel Gabriel is a good example. It shows the angel in dark green and blue garments with the edge of a bright red sleeve showing from under the angel's tunic. The modeling of the figure, especially the face, is highly worked in a restrained, classical style. The bright highlights on the face and clothing are typical of the time and add an electric, almost nervous, aspect to the ikon. Gabriel carries a staff and bends in deference to the left. This is an indication that this ikon may come from a Deesis tier of an iconostasis. The style is called Paleologian after the aristocratic family that usurped the Nicaean throne and retook Constantinople from the Latins in 1271.

Entering Constantinople, which was hurriedly abandoned by the last Latin Emperor and Catholic Patriarch in a Venetian ship crammed with as much treasure as they could quickly cart off, the returning Greeks found their city dirty, defiled, and with large abandoned tracks of ruins. Constantinople was a but a shadow of its former grandeur and the city that had been the most fabulous and beautiful in Christendom was gone. Seventy years of Latin rape, exploitation and neglect of the city was everywhere to be seen. What wasn't too heavy to move had been taken away to Venice, Rome or Barcelona. Most of the ancient bronze statues that had survived the sack of the city had been hauled off as scrap metal by the Venetians, to be recast as cannon or struck as cheap coins. The Latins had even sold the lead roof of the Imperial Palace of Blachernae. When reoccupied by the Byzantines it was so filthy a complete cleaning and renovation was required to make it habitable again. Many of the famous religious relics of the city were gone, too; for example, the famous Crown of Thorns, which was said to have sat upon Christ's head during the Passion was sold by the Latin rulers of the City to France, where it was to rest in Sainte Chapelle in Paris for hundreds of years to come.

The Paleologians occupied the throne of Constantinople for the next 180 years, but circumstances were quite different than those enjoyed by their Imperial predecessors. Money was very short and what funds were available were spent to defend the shrinking borders of the Empire. When part of the dome and eastern arch of Hagia Sophia collapsed in 1346's it was some time before the needed repairs could be done because of a shortage of funds. A substantial donation from the Great Prince of Moscow made the restoration possible. It caused a great deal of grief in the Orthodox world that the once powerful Byzantine Emperors were now begging for handouts from their former client states and vassals to repair the Great Church of Hagia Sophia. Even the Imperial Crown Jewels were pawned and replaced by diadems of cut glass and gilded leather. To the surprise and dismay of guests at Imperial Paleologian dinners in the 14th century, they were no longer served on silver and gold. Embarrassingly, in place of these splendid settings were laid cheap ceramic and pewter.

In spite of the wretched circumstances of the Imperial Government, private aristocratic families of Byzantium were still extremely wealthy and continued to build fabulous palaces and establish glittering churches - although on a reduced scale in comparison to their ancestors. The second ikon on the left is from the apse in the side chapel of the Church of St. Savior in Chora in Istanbul, which was rebuilt and redecorated by a erudite and highly cultured high official of the Byzantine Court, Theodore Metochites, around 1300. This building contains one of the most extensive surviving decorative schemes of any Byzantine building of the time and is critical to an understanding of the artistic style in aristocratic circles of the time. The painting depicts St. Cyril of Alexandria, one of the fathers of the church. It dates from around 1350 and is interesting because it reveals a number of trends in Byzantine art of the time; including an increased emphasis on caricature, angularity, more intense use of color and a love of decorative elements.

The miniature ikon below St. Cyril is of St. John Chrysostom, a former Bishop of Constantinople who lived in the 5th century. His enlarged forehead, tiny eyes and pinched face, while loyal to the accepted image of St. John, are shown in an exaggerated and manneristic fashion, typical features of Paleologian art. Below the ikon of St. John is a detail from a large mosaic of St. George from the vaults of the Chora Church. Although the face has the same fresh and idealistic look (similar to his depiction on the ikon from Sinai) of the saint which had been loyally adhered to by Byzantine artistic canons for almost 1,000 years, certain elements in the figure, such as the egg-shaped head, and excessively decorated robes are hallmarks of the Paleologian style shown here at its zenith.

The next image at left shows the Theotokos holding Christ tightly to her face. It is an angular painting which perhaps shows the mastery of the artist, who probably drew the figure freehand, without reference to pattern books often used by artists less sure of their talent. The Virgin's eyes peer off into the center of the chapel apse, while a chubby infant Christ, settles heavily into her arms and tugs at her robe. It's a curious ikon, detached; the indirect look of the Virgin's seems distracted. Consciously or unconsciously, the artist's depiction of the Theotokos reflects the uncertainty of the time in which it was painted. After the initial euphoria of the recapture of Constantinople, Byzantium was soon torn apart by domestic divisions and civil wars. Although it was barely noticed by the Byzantines at the time, who were obsessed with their own internecine conflicts, the Ottoman Turks were just beginning their fateful conquest of the heartland of the Empire, Western Asia Minor. This would ultimately result in the Islamic swallowing up of the Byzantine Empire by the Turks.

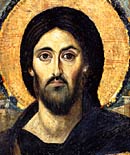

Art historians have generally concluded that the last decades of Byzantine art - those years leading up to the conquest of the city by the Ottoman Sultan Mehmet II on May 29, 1453 - was a period of decadence and a serious decline in art patronage as Constantinople struggled for its very life. Beyond the walls of the city, in distant parts that still held out against the Turks, a valiant attempt was made to rally Hellenism and save the ancient legacy of Byzantium. In the town of Mistra near Sparta in Greece many artists and intellectuals from the city took refuge. In one of the last outposts of the Empire they attempted to rekindle the culture they had inherited from Greece, Rome and Medieval Byzantium. For a few years the flame burned brightly. The last image at left shows a detail from a painting of the Nativity which comes from one of last of Mistra's churches to be decorated before the Turkish army overwhelmed them as well. The Virgin has just given birth to our Lord who is wrapped in swaddling clothes and attended by a cow and a donkey. The image of the Theotokos is one of the most intense we still have from Byzantium. It shows the artistic genius that the 1100 year old culture of Byzantium could still muster in its twilight years.

Next chapter: Ikons in the Modern Age