Ikon History - Earliest Christian Ikons

After the death and resurrection of Christ the new faith spread rapidly throughout the Roman world and the Near East. The stories of the Apostles and early witnesses who had seen and known Christ Himself were eagerly listened to by converts to the new faith. Naturally, people who had seen Christ asked for descriptions of His appearance. At some point people began to create and distribute paintings of Christ. This also included his disciples and the really martyrs of the Christian faith. The earliest images we know of was a statue of Christ which Eusebius, an important early Christian bishop, says had been set up in Caesarea-Phillipi (Paneaus) by the woman healed by Christ of an issue of blood. He also notes that in his time there were very ancient images of Peter and Paul. However, the church was somewhat divided about images of Christ.

Eusebius refused to send the wife of Caesar Callus an image of Christ, for he thought it idolatrous and a violation of biblical injunctions. Some regional churches were against images as well, a local Spanish synod in 305 said images in churches were forbidden. However, the number of examples of paintings of the nativity and allegories of the Good Shepherd from around 250 AD, show how common Christian paintings had already become. The growth of images was concurrent with the development of the doctrine of the Incarnation of Christ and is closely tied to the growing awareness of this essential element of the Christian faith.

We can reasonably suppose that these early paintings of Christ and His saints were, at first, simply looked upon as realistic depictions of people; much like the casual way we look at photographs today. Very quickly certain characteristics of Christ and the saints where established as canons for their future depiction. For example, Peter the Apostle is shown slightly bald, with grey curly hair and a beard. Paul is show more bald in front with straight brown hair, a beard, a thick neck and sometimes with a bit of a paunch. These images most certainly originated in Rome, where people knew the two apostles and their physical appearance well. An example of an early ikon of St. Peter is shown at left. Above him are circular ikons of St. John, Christ and the Virgin.

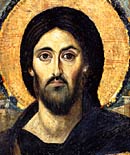

In early Christian times there were two images of Christ that were more or less standardized. One was of a young, idealized and clean shaven "hero" type. The second was the image we are familiar with today - a man in his late 20's or early 30's with long hair tied at the back, a smooth beard, high forehead, long nose, and dressed in a loose, long robe and cloak.

In ancient Rome and throughout the Roman world the Emperors, upon their accession to the throne - and then throughout their reign - distributed paintings or statues of themselves and often their families to cities around the Empire. These images would be placed in prominent places by the city fathers. They were intended to locally represent the presence of the Emperor and his power. Incense and sacrifice were often offered to these images to prove a local municipality's devotion to Rome or the Imperial Family. Individuals who wanted to make a show of their loyalty might do the same in their own homes.

Christians had a hard time participating in the public ceremonies which involved sacrifice to the Emperor's portrait. For most people these ceremonies where simply a formalistic part of civic life and had little real meaning their lives. Few people really believed the Emperor was a god. The fact that Christians were unwilling to offer incense or Sacrifice was looked upon as a treasonous act. Many Christians died rather than worship the Emperor's image - even if it was only a show in people's eyes.

Early Christians looked not on earth for their King or Emperor, but to Heaven. It isn't known exactly when images of Christ began to take on many of the attributes of Kingship, but at some point Christ's poor robes were transformed into the Royal colors of blue and Imperial Purple, while he sat upon a splendid throne and silken cushions, his feet upon a jeweled footstool. Around his head gleamed a golden halo with rays showing the arms of the cross. Halos came from Persia and had longed been a symbol of divinity or holiness.

The ikon shown at left is painted in wax colors by means of heated spatulas. His robes are painted in Imperial Purple, which was reserved for the Emperor alone. His hand is raised in blessing and he holds a gold-covered gospels encrusted with gemstones. The ikon probably dates from the reign of the Emperor Justinian (527 - 565) and may be a dedicatory gift from him to the Monastery of St. Catherine, which he had built around 548. The ikon in the center is of the Virgin accompanied by Saints Theodore and George. Behind them angels gaze upon the blessing hand of God emerging from heaven. All of these three ikons are striking in that they strive to depict real people in naturalistic settings; they have all the characteristics of genuine portraits.

Next chapter: Ikons of Mary, the Theotokos