Ikon History - Middle Byzantine Period

In the early 8th century there erupted a intense controversy in the Orthodox Church over the use of ikons in worship and prayer. The two sides in the battle were called ikonoclasts (opposed to ikons), and ikonodules (in favor of ikons). The argument over ikons had been going on in the church for several hundred years. Basically it broke down to whether the veneration of ikons was idolatry. Some people were offended by the kissing of images and the offering of incense and lighting of candles before them. It is very difficult to explain the nuance in the original argument in English. The ikonoclasts claimed that ikons were being worshiped, while the ikonodules argued that it was only veneration of ikons and a type of 'salute' of the original depicted in the ikon. The actual Greek word for this veneration is proskynesis, and it the same veneration that was given to the Emperor. It involved humble reverence and bowing, but it was not worship.

The Emperor Konstantine the Fifth put together a council of his supporters and pushed through an edict in 730 which banned images. This council was uncanonical and represented the first time an Emperor inferred directly in the affairs of the church, ignoring the other patriarchs, including the Pope in Rome.

Many monks, nuns, lay people and priests died defending the images of Constantinople, which were torn down by mobs supported by Imperial troops. The Emperor didn't stop with images for he ordered monks and nuns to wed and executed those who refused. Many of the Emperor's ideas came from the eastern part of Asia Minor he came from and was supported by the army which was recruited from the same area.

The edict was observed strictly in Constantinople but only to varying degrees around the Empire. It was rescinded for a few years, then reinstated once again, finally ending in 843 with the total victory of the Orthodox.

During Iconoclasm the unbroken tradition of ikon painting was severely shaken. Technique suffered greatly and we can suppose ikons created during Ikonoclasm had a rougher, perhaps even somewhat crude, appearance, since by this time almost all ikons were being produced in monasteries by monks who had little use for Hellenism and the fine technique of 5th and 6th century icongraphy.

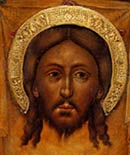

When ikon painters became working openly after 843 there was much to do. There were many churches that immediately needed decoration. It took many years for artists to rediscover and relearn the old techniques and styles. Materials for painting and mosaic work were also hard to find. Within 100 years the artistic quality of Constantinoplian ikon painting was the near-rival of anything ever done in the city. Ikons were created in egg tempera, mosaic, ivory , glass, marble, gold and precious stones. By the time the twice life-sized mosaic on the left was created in the south gallery of Hagia Sophia, around 1185, Byzantine art had attained a refinement and beauty that would never be achieved by them again. The mosaic depicts Christ enthroned as Pantokrator; on the left (not shown) is Mary, the Mother of God, while on the left (also nor shown here) is John the Baptist. Considering the location of the mosaic ikon, and the quality of the work itself, this is the product of one of the top artists of the time. Unfortunately, as with most ikon art, we do not know the name of its creator. The tiny size of the cubes and subtle coloring of the face is astounding. This mosaic is, perhaps, the finest surviving artistic achievement of Byzantium and ranks among the most important works of art in the world.

This level of achievement lasted past the fall of Constantinople to the Latin Crusaders in 1204 and the reestablishment of Byzantine rule in the City under Emperor Michael Paleologius in 1261. However, within a hundred years of the recovery of the City the style and quality of painting seems to decline. The lower icon on the left dates from 1363 and is typical of the work of the time. It shows Christ Pantokrator in virtually the same mode as the Hagia Sophia mosaic, but the drawing is awkward, the coloring is a bit garish and the ikon has an almost hulking feeling. It was commissioned by two high officials of the Byzantine Court, the Grand Stratopedarch Alexius and the Grand Primicerion John; who are depicted as small figures in the lower margins of the ikon. These two gentlemen are recorded as having been founders of a monastery dedicated to the Pantokrator, so this ikon may be associated with that foundation.

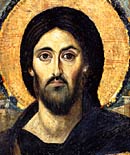

The mosaic ikon at the bottom also comes from the upper gallery of Hagia Sophia. It dates from the reign of Emperor John Comnenus and is of the Virgin "Nikopeia" which was the sacred ikon of Byzantine Emperors which was carried into battle with them. The original icon, of which this mosaic is a much enlarged copy, was stolen during the Latin sack of Constantinople in 1204 and how is enshrined on the left hand-side of the altar of St. Mark's in Venice.

Next chapter: Early Russian Ikons